Nuclear Fusion and the Great Global Gamble

ENERGY, 22 Mar 2021

Stu Campana | Alternatives Journal - TRANSCEND Media Service

Isaac Newton risked his sight for science; what will we risk for renewable energy?

Isaac Newton was pondering how to test the hypothesis that colour is created through pressure on the optical nerves when, suddenly, he had an epiphany. With startling confidence – or perhaps simply unnerving indifference – he stuck a needle into the back of his eye. Newton calmly noted the effect it had on his vision. Thus was another scientific advance made by the father of classical mechanics.

Isaac Newton was pondering how to test the hypothesis that colour is created through pressure on the optical nerves when, suddenly, he had an epiphany. With startling confidence – or perhaps simply unnerving indifference – he stuck a needle into the back of his eye. Newton calmly noted the effect it had on his vision. Thus was another scientific advance made by the father of classical mechanics.

Newton risked his physical well-being through the needle experiment, but not much else. The equipment necessary for the experiment (one – hopefully sterilized – needle) was as inexpensive as it gets.

Today scientists at MIT face a different kind of risk. Having failed to show sufficiently promising results within the time allotted to them, their nuclear fusion experiment has lost its millions of dollars in federal funding, with half of its scientists being dismissed. It was a gigantic investment aiming for gigantic results, but theirs is a common story.

Nuclear fusion is the poster child of a new permutation of scientific risk: one in which global financial wagers are placed against the probability of success. Scientists in the Newtonian era played for stakes much lower than global survival.

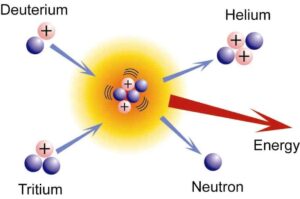

Clean, cheap and unlimited, nuclear fusion is the reaction that powers stars. Attempts to replicate it on a smaller scale seem to be theoretically possible, but success on the level of nuclear fission – which is currently the source of all the world’s nuclear power – remains decades away.

Big scientific leaps are now rarely made via small-scale experiments with few resources. They require time, money and resources and, with climate change barreling down on us, they come with opportunity costs. The new risk is thus equally about time and money in a world with limited amounts of both.

“It’s expensive research that can only be done at large scales,” says Steve Cowley, director of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy. “For $20 billion in cash I could build you a working reactor. It would be big, and maybe not very reliable, but 25 years ago we didn’t even know if we’d be able to make fusion work.”

A $20 billion investment requires nerve no less dramatic than Newton’s, but the additional wrinkle is that there are opportunity costs associated with such a project. “If we spent [even] $6 billion to study energy storage we’d have a massive deployment of solar technology,” argues Christopher Paine, director of nuclear programs with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

In the face of climate change, nuclear fusion is the big gamble. And everybody knows the stakes. Win, and our energy and climatic problems become a thing of the past. Lose, and it’s likely too late to shift those billions of dollars and international research toward another energy saviour.

The risk – both professional and societal – weighs as heavily on individual scientists as it does on institutions and countries. For years since the theoretical discovery of fusion by Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann at the University of Utah, research in fusion has been secretive and poorly funded. In a 2012 paper, Dr. Robert Pike describes the last two decades as a “time of exile” where fusion research “essentially went ‘underground’, being pursued in various laboratories worldwide […]. Much progress has been recorded despite difficulties not only in terms of funding, but also in the area of publication where both editorial staffs and reviewers are often prejudicial about the very idea.”

Only in the last several years has fear of climate change brought fusion research back into the mainstream. And still proponents are scorned as deluded evangelists who are throwing away their careers.

Reputational risk is something Newton knew all about. A secret alchemist, he spent 30 years hiding his search for the philosopher’s stone from the world. Even a scientific giant like Newton couldn’t be seen attempting to transmute iron into gold. And yet, if it worked, he’d be a hero.

Meanwhile, the $19.8 billion International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project is scheduled for completion in 2020, with the first experiments to follow by 2027. More resources could likely speed up progress for this international collaboration, but that’s a lot of time and money just to see if something will work. A lot of reputations are being staked on these projections. Moreover, nobody can be certain that construction will continue at its current pace.

ITER aside, the world hasn’t yet gone all in on fusion for three main reasons:

- The sums of money involved are enormous.

- Fusion has proven extremely resistant to deadlines.

- The results generated thus far cannot be explained through any known physical theory.

There have always been a few willing to risk their own careers on a gamble like nuclear fusion, but now the whole world is inching closer to going all in. More than a few state and private funders are certain to lose millions (or billions) in search of a working fusion reactor. Their great hope is to be the first to the prize. And the world hopes with them because if everyone puts all their chips on fusion, there’ll be nothing left for the other renewable alternatives when climate change puts an end to the game. That’s a risk that would startle even the great Isaac Newton.

___________________________________________

Stu Campana is an international environmental consultant, with expertise in water, energy and waste management. He is the Water Team Leader with Ecology Ottawa, has a master’s in Environment and Resource Management and writes the A\J Renewable Energy blog.

Go to Original – alternativesjournal.ca

Tags: Climate Change, Electric Energy, Energy, Fission Energy, Fusion Energy, Global warming, Nuclear Energy, Renewable Energy, Solar Energy, Sustainable energy

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.