Wall Street’s Cooked Books Fueled the Financial Crisis in 2008–It’s Happening Again

CAPITALISM, 26 Apr 2021

Jon Schwarz and Ryan Grim | The Intercept - TRANSCEND Media Service

The Bigger Short

20 Apr 2021 – It’s only when the tide goes out that you learn who’s been swimming naked,” the billionaire investor Warren Buffett has famously said.

During the crash of 2008, the whole world learned just how dangerously nude Wall Street was. Now evidence is accumulating that suggests that many financial institutions are skinny-dipping once more — via similar types of lending that could lead to similar disasters as the water recedes again due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

A longtime industry analyst has uncovered creative accounting on a startling scale in the commercial real estate market, in ways similar to the “liar loans” handed out during the mid-2000s for residential real estate, according to financial records examined by the analyst and reviewed by The Intercept. A recent, large-scale academic study backs up his conclusion, finding that banks such as Goldman Sachs and Citigroup have systematically reported erroneously inflated income data that compromises the integrity of the resulting securities.

The analyst’s findings, first reported by ProPublica last year, are the subject of a whistleblower complaint he filed in 2019 with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Moreover, the analyst has identified complex financial machinations by one financial institution, one that both issues loans and manages a real estate trust, that may ultimately help one of its top tenants — the low-cost, low-wage store Dollar General — flourish while devastating smaller retailers.

This time, the issue is not a bubble in the housing market, but apparent widespread inflation of the value of commercial businesses, on which loans are based.

Those who remember news coverage at the time know that the tale of the 2008 financial implosion involved an enormous swirl of numbers and acronyms. But when boiled down to its essence, the story of the housing bubble of the 2000s, and plausibly Wall Street’s actions today, is simple: It’s counterfeiting.

Traditional counterfeiters print money: pieces of paper that supposedly are worth their face value but in fact are worth nothing.

Wall Street counterfeiters during the housing bubble printed securities: pieces of paper that supposedly were worth their face value but in fact were worth much less.

This time, the issue is not a bubble in the housing market, but apparent widespread inflation of the value of commercial businesses, on which loans are based.

In the mid-2000s, companies like Countrywide Financial Corp. issued so-called liar loans. Often without informing the borrowers themselves, Countrywide and other loan companies would claim that, say, a bartender was making $500,000 a year, allowing them to borrow enough money to buy a home that they couldn’t possibly afford. The originating banks then took the loans, which could never be paid back on the bartender’s real income, and securitized them — i.e., bundled them together into a trust, which was then sliced up into bonds called residential mortgage-backed securities. These securities behave similarly to regular bonds, coming with a quality rating and an interest rate that they pay out. These securities, sold to credulous investors such as pension funds, were the counterfeit paper of the period, remaining valuable as long as home prices rose, which allowed the bartender to refinance or sell the property when the payments got out of hand.

When prices stopped rising, the housing bubble collapsed, and those at both ends of the transaction were ruined. Borrowers, unable to sell or refinance, were thrown out of their homes. Many investors, who generally thought that they were buying risk-free bonds, lost huge sums. But by then, middlemen like Countrywide’s CEO Angelo Mozilo had taken home hundreds of millions of dollars from the fees for originating and packaging the mortgage loans.

Now it may be happening again — this time not with residential mortgage-backed securities, based on loans for homes, but commercial mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS, based on loans for businesses. And this industrywide scheme is colliding with a collapse of the commercial real estate market amid the pandemic, which has business tenants across the country unable to make their payments.

John M. Griffin and Alex Priest are, respectively, a prominent professor of finance and a Ph.D. candidate at the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin. In a study released last November, they sampled almost 40,000 CMBS loans with a market capitalization of $650 billion underwritten from the beginning of 2013 to the end of 2019.

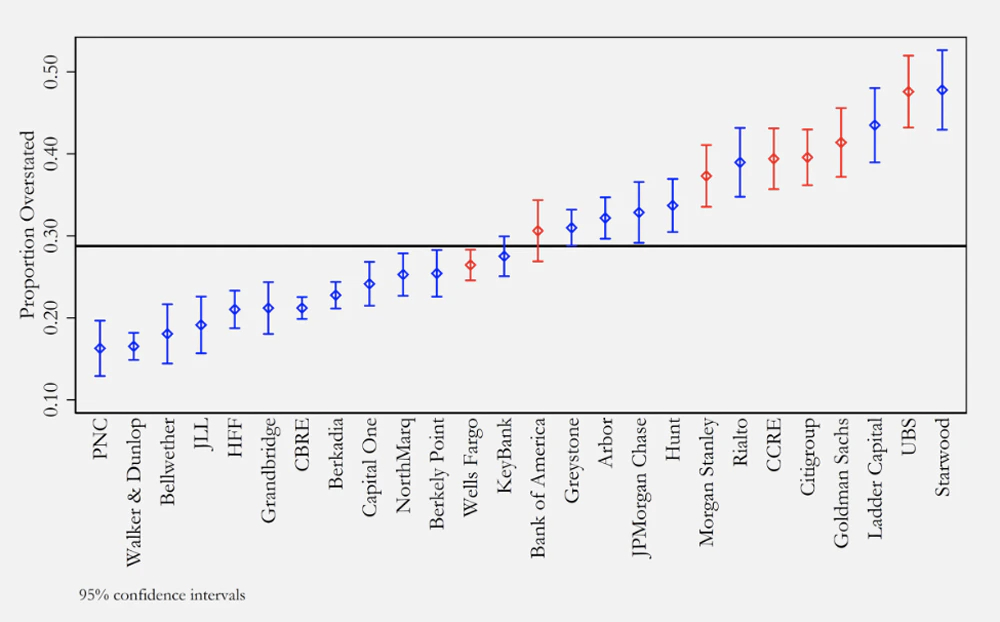

“Overall,” they write, “actual net operating income falls short of underwritten income by 5% or more in 28% of loans.” This was just the average, however: Some originators — including an unusual company called Ladder Capital as well as the Swiss bank UBS, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Morgan Stanley — were significantly worse, “having more than 35% of their loans exhibiting 5% or greater income overstatement.” The below graph from the paper illustrates just how prevalent this issue is with some of Wall Street’s biggest names:

The paper explains that the authors are “interested in studying intentional income overstatement.” In an interview, Priest said that “we find that the direct inflation of past financials is common practice in the industry” and “our tests demonstrate that this really doesn’t seem to be a pattern that’s driven by coincidence. … It’s hard to argue that these originators are just naive,” making innocent mistakes.

One way the authors approach the issue is by examining whether lending institutions overstated borrower income more or less frequently during the first half of the seven years it covers (i.e., 2013-15) compared to the second half (2016-19). Unintentional overstatement should have occurred at random times. Or if lenders were assiduous and the overstatement was unwitting, one might expect it to diminish over time as the lenders discovered their mistakes. Instead, with almost every lender, including Ladder, the overstatement increased as time went on.

These income overstatements might cause defaults under any circumstances. But it has been particularly dangerous in a severe economic downturn like the one caused by the coronavirus pandemic. “There is an economically and statistically significant relation,” Griffin and Priest write, “between originator income overstatement and distress.” That is, loans where the fundamentals were misstated are, unsurprisingly, more likely to go bad during this crisis. All these banks are swimming naked.

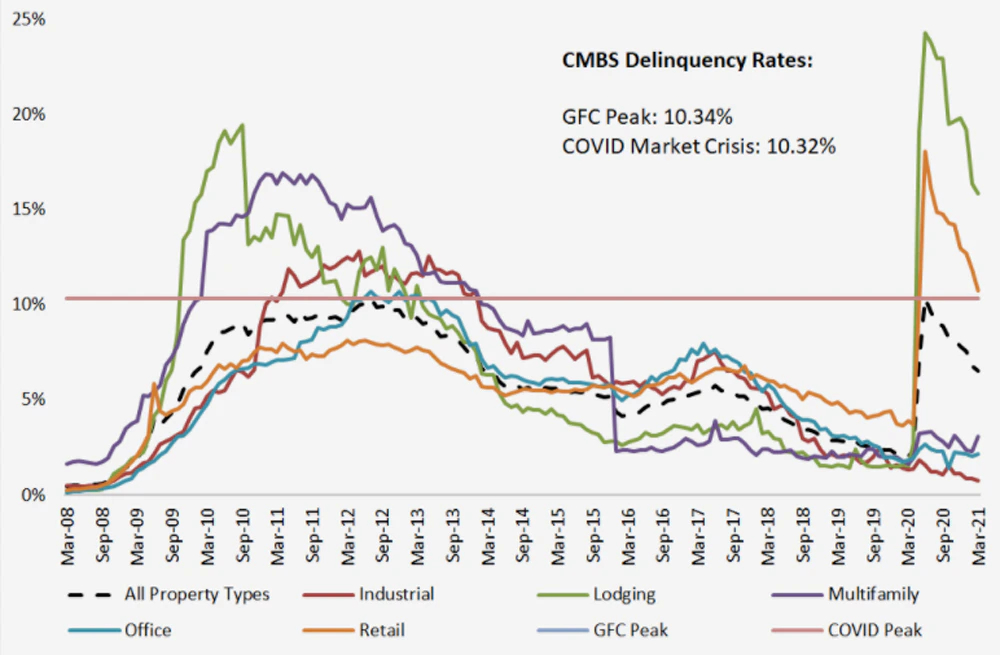

The level of distress in the industry can be seen in this graph created by Trepp, a company that produces a specialized database for the commercial real estate and structured finance industries. The overall delinquency rate for commercial mortgage-based securities shot up last year to the same level as the peak during the last economic collapse. And CMBS delinquencies for retail and lodging businesses reached unprecedented heights.

This is not just the conclusion of academics.

John Flynn has worked in commercial real estate for decades, including stints at GMAC Commercial Mortgage and the ratings agencies Moody’s and Fitch. He now provides advisory and consulting services for CMBS investors, borrowers, and lawyers.

In conversation, Flynn comes across much like the investor Michael Burry in “The Big Short,” combining a love for financial arcana with deep outrage at how the system screws the little guy. “I’m not a perfect angel,” says Flynn. “But there has to be a limit.”

Flynn’s whistleblower complaint filed with the SEC states that he has identified “about $150 billion in inflated CMBS” issued since 2013 by banks such as Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank and the “shadow bank” Ladder Capital.

But it’s easiest to understand what seems to be happening in the CMBS market by looking at a single trust.

Take one called “LCCM 2017 LC26,” which Flynn has examined in fine-grain detail. What he’s found appears similar to the residential mortgage trusts of the 2000s, with some newfangled twists.

LCCM 2017 LC26 consists of 57 commercial real estate loans bundled together, with a total unpaid principal balance of $625 million. LCCM stands for Ladder Capital Commercial Mortgage Securities, the trust depositor. 2017 is the year the trust was created. LC stands for Ladder Capital Finance, the trust’s sponsor and mortgage loan seller. 26 means it’s the 26th in a series.

Ladder Capital is best known for being one of former President Donald Trump’s biggest creditors.

LCCM and LC are both subsidiaries of Ladder Capital, a small Wall Street firm best known for being one of former President Donald Trump’s biggest creditors. According to Trump’s 2020 financial disclosure, companies he controls owe Ladder a minimum of $110 million, including a mortgage on Trump Tower for at least $50 million. Jack Weisselberg, the son of Trump Organization Chief Financial Officer Allen Weisselberg — considered the architect of Trump tax and financial strategies — is a director at Ladder and reportedly a senior loan-origination officer there.

Ladder was founded by three former executives who all worked at Dillon Read Capital Management, an internal hedge fund at UBS that collapsed in 2007 after making investments in the subprime housing market. Ladder is a real estate investment trust that also produces and sells commercial mortgage-backed securities. It’s the type of nonbank financial institution that has proliferated since Congress passed the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act in an attempt to rein in Wall Street in the wake of the financial crisis. Ladder Capital did not respond to several requests for comment.

According to the documentation for a memo Flynn produced for journalists, he found problems with 13 of the 57 loans in LCCM 2017 LC26. The 13 loans were worth $203 million, or 32.5 percent of the total value of the trust’s unpaid principal. Finding those problems took enormous legwork, not the type of diligence typically conducted by investors who acquire these securities. The documents that undergird trusts like LCCM 2017 LC26 are publicly available but only with access to a premium subscription service. The documents produced to vouch for the quality of a loan are not typically investigated by investors — or, in most cases, ratings agencies — who rely on the word of the summary and prospectus produced by the issuer of the security. The offering circular for LCCM 2017 LC26 is 407 pages long, plus hundreds more pages of appendices.

The circular includes standard “safe harbor” language emphasizing that Ladder cannot predict the future performance of the bonds issued by the trust. But as Flynn found, the issue was Ladder’s representations of the past.

First, Flynn discovered that the 13 loans had previously been packaged into other trusts, which allowed him to compare how previous lenders had characterized the loans versus how Ladder was now characterizing them. For instance, if a previous lender had said a property had generated a certain amount of income in 2015, you would expect that Ladder would provide the same numbers for that year. But in many cases, it didn’t. Sometimes the numbers weren’t even close.

If a previous lender had said a property had generated a certain amount of income in 2015, you would expect that Ladder would provide the same numbers for that year. But in many cases, it didn’t.

Even if investors did attempt to scour the documents for anomalies, doing so would have been extraordinarily difficult. Flynn had to engage in laborious detective work, as the names or addresses of the 13 relevant borrowers in LCCM 2017 LC26 were often different from their listings in previous trusts. In order to find previous loan documents to compare to current ones, Flynn often had to get creative. For instance, Flynn looked for matches between tenants or square footage of the property being purchased to determine that a loan in LCCM 2017 LC26 was the same as the one in a previous trust.

Flynn then looked at two key financial metrics for each loan: the property’s net operating income, or NOI, and net cash flow, or NCF. In the world of commercial mortgages, a property’s NOI and NCF hold a significance similar to a borrower’s income for residential mortgages. The higher the numbers, the more creditworthy you are, allowing you to borrow more at lower interest rates.

The previous trust’s servicers had reported the NOI and NCF. Then when Ladder Capital packaged them into a new trust, Ladder also reported the NOI and NCF. But the numbers didn’t match.

For instance, one of the loans in LCCM 2017 LC26 was for $14.1 million to refinance the mortgage on an office building in Wilmington, Delaware. The building was 160,500 square feet, all of which was leased by Verizon.

According to the old trust, the building’s NOI for 2016 was $1,285,465. But according to LCCM 2017 LC26, the building’s NOI for 2016 was $1,717,350 — 33.6 percent higher.

According to the old trust, the building’s NCF for 2016 was $1,273,427. But according to LCCM 2017 LC26, the building’s NCF for 2016 was $1,717,350, or 34.9 percent higher.

By Flynn’s calculations, as of April 2019, the 13 anomalous loans had, in aggregate, total inflated NOIs of $2.5 million and NCFs of $3.85 million.

This makes them look much like the loans of the housing bubble. Flynn alleges in his SEC complaint that companies like Ladder Capital have an incentive to exaggerate a business’ income. As Flynn explains in his memo, Ladder “takes profits and fees from originating, arranging, and selling the loans into CMBS trusts, and then selling the securities.”

Flynn also alleges in the complaint that changes in names and addresses when loans are moved out of old trusts and into new ones are not an accident but suggestive of deliberate obfuscation. “The correlation of name and address changes with inflated numbers,” he says, “is something like 95 percent.”

Ironically, Ladder Capital’s website describes commercial real estate underwriting — i.e., the accurate assessment of the creditworthiness of borrowers — as its “core competency.”

That’s the part of the story that’s similar to the 2008 crisis. But it gets even stranger.

Ladder Capital does not just make loans. As its website explains, it does indeed engage in “originating senior first mortgage fixed and floating rate loans collateralized by commercial real estate.” But it also makes money “owning and operating commercial real estate.”

The money for the loans that make up LCCM 2017 LC26 did not come from Ladder. Rather, it borrowed the money on a short-term basis from Wells Fargo, and then one of its subsidiaries, Ladder Capital Finance LLC, loaned it to companies that wished to take out a mortgage to buy commercial property (or refinance an existing mortgage). It then packaged these 57 loans into the trust. But of the 57 loans, 23 of them, totaling $76.7 million, were made by Ladder Capital Finance LLC to another Ladder subsidiary in the real estate business, Ladder Capital Finance Holdings LLLP. In other words, contrary to the admonition to neither a lender nor a borrower be, Ladder was both in the same transaction.

In LCCM 2017 LVC26, 21 of the 23 loans were used by Ladder Capital to purchase properties where Dollar General is Ladder Capital’s sole tenant. (The other two loans Ladder Capital made to itself were used to buy properties with tenants including Bank of America and Walgreens.) Ladder’s relationship with Dollar General is significant for the company: During a 2020 earnings call, Ladder’s co-founder and president Pamela McCormack stated that “our three largest tenants are Dollar General, BJ’s, and Walgreens.”

This, Flynn contends in his memo, could allow Ladder Capital to make money coming and going. First, Ladder subsidiaries would get the fees for originating and packaging the loans. Next, the seemingly exaggerated NOI and NCF numbers for the 13 problem loans push down the interest rates for the entire trust, including Ladder Capital’s loans to itself.

That’s where Dollar General comes in. Because Ladder Capital is paying the trust a lower interest rate on its mortgages than it would be if the cash flow and income numbers had not been increased, its monthly loan services costs for its properties logically must be lower. And if that lower cost is then translated into a cheaper rent for the tenant — in this case Dollar General, though the logic would apply generally — that means the store’s overall costs would go down significantly, especially compared to other retailers operating in the same areas.

Rent is the largest cost for many retailers, particularly understaffed stores run by underpaid employees and stores with low-margin sales of low-priced consumer products.

Daniel Stone worked for four years for Dollar General as a market planning analyst, where he was responsible for finding prime locations for new stores. He said the rent at a potential store was the most significant factor he would look at. “Rent was the largest year-to-year cost,” he said, noting that many stores employed just two or three full-time workers. If the rent on a potential location was too high, he said, the company would push back, explaining that they could only open a location at a particular price. Often, he said, as much as $10,000 a year would be knocked off the annual rent by the would-be landlord, and the store would be opened.

He was fired in April 2020, he said, after expressing concerns about the way workers were being treated in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. “They classify you as a manager so they don’t have to pay you overtime,” Stone said.

Tom Barrack, a close friend of Trump’s and a leading real estate investor, made the same point about the significance of rent costs for low-margin retailers earlier in 2020 — and warned about the fragility of the CMBS market during the pandemic. “When commerce stops and they can’t pay rent,” Barrack said on Bloomberg TV, “and they can’t pay interest on the debt, and then the banks or the intermediaries can’t pay the investors, it all collapses.”

Moreover, the spread of Dollar General stores and stores like it is widely understood to be bad for the health of communities where they’re located. They sell snacks, drinks, and canned foods — which makes regular supermarkets reluctant to open locations nearby — but limited or no produce or fruit, thereby creating food deserts. Communities across the U.S. have tried to stop the opening of dollar stores.

Nonetheless, Dollar General’s stock has gone up almost 150 percent in the past five years. Now, as tens of millions of Americans still face economic hardship and are desperate to spend as little as possible, Dollar General is trading near its highest level ever.

So we know who seemingly benefits from LCCM 2017 LC26. The victims of it are more diffuse but just as real.

There are the investors, including pension funds and college endowments, who will be left holding the bag if borrowers received larger loans than they could service and end up defaulting.

“Just in the commercial mortgage market, you have $4.5 trillion,” Barrack said. “And that money needs to keep recycling to keep people moving and to keep employers in their buildings so that they can hire employees. If that stops, margin calls at the banks, to all the intermediaries. We talk about the nonbank banks and the shadow banks that after Dodd-Frank were instituted in order to create more liquidity in the system for mortgages — when that stops, everything stops.” That is, if stores can’t pay their rent, their landlords can’t pay their mortgages, less money flows into the trusts created from those securitized mortgages, investors in the trust don’t get paid, and the whole system freezes.

Other victims include the businesses that are forced to raise capital without the advantage of artificially low interest rates. “Misrepresentations made in the loan sales allow complicit lender/owners to subsidize and decrease interest rates payable for their own loans,” Flynn argues in his memo, which gives them “a competitive advantage over competing retailers.”

That brings us to today. “The pandemic has justifiably renewed concerns about the fragility of the CMBS market and the possibility of a new, commercial, mortgage crisis,” according to a memo from Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, an international white-shoe law firm that specializes in large-scale, complex lawsuits.

There’s been, the firm warns, “a steady drumbeat of warnings regarding troubling origination and underwriting practices impacting the long-term stability of the market.” This has already translated into litigation similar to that during the 2008 meltdown: In February, the SEC filed a lawsuit against a credit rating agency for allegedly manipulating its CMBS rating methodology. Last September, another credit rating agency paid $2 million in fines to settle a similar SEC suit.

Flynn believes that a reckoning is coming, one way or another. “It’s incredible but not surprising that Wall Street is repeating the same kind of shenanigans, given there were no real repercussions after the subprime crisis,” says Flynn. “CMBS borrowers and investors will face more frequent defaults and higher losses from these kinds of issues as CMBS 2.0 credit and loan quality is laid bare by Covid-19.”

__________________________________________________

Go to Original – theintercept.com

Tags: Banksters, Big Banks, COVID-19, Capitalism, Corruption, Elites, Finance, Fiscal Paradises, Greed, Inequality, Mafia, Money laundering, Organized crime, Post-capitalism, Profits, Super rich, USA, Wall Street

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.