The G.I.s mainly kept to themselves what they had done, but there had been other witnesses to the atrocity—American helicopter pilots and Vietnamese civilians. The first investigations of the My Lai case, made by some of the officers involved, concluded (erroneously) that twenty civilians had inadvertently been killed by artillery and by heavy cross fire between American and Vietcong units during the battle. The investigation involved all the immediate elements of the chain of command: the company was attached to Task Force Barker, which, in turn, reported to the 11th Light Infantry Brigade, which was one of three brigades making up the Americal Division. Task Force Barker’s victory remained just another statistic until late March, 1969, when an ex-G.I. named Ronald L. Ridenhour wrote letters to the Pentagon, to the State Department, to the White House, and to twenty-four congressmen describing the murders at My Lai 4. Ridenhour had not participated in the attack on My Lai 4, but he had discussed the operation with a few of the G.I.s who had been there. Within four months, many details of the atrocity had been uncovered by Army investigations, and in September, 1969, William L. Calley, Jr., a twenty-six-year-old first lieutenant who served as a platoon leader with Charlie Company, was charged with the murder of a hundred and nine Vietnamese civilians. No significant facts about the Calley investigation or about the massacre itself were made public at the time, but the facts did gradually emerge, and eleven days after the first newspaper accounts the Army announced that it had set up a panel to determine why the initial investigations had failed to disclose the atrocity. The panel was officially called the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident, and was unofficially known as the Peers Inquiry, after its director, Lieutenant General William R. Peers, “who was Chief of the Office of Reserve Components at the time of his appointment. The three-star general, then fifty-five years old, had spent more than two years as a troop commander in Vietnam during the late nineteen-sixties, serving as commanding general of the 4th Infantry Division and later as commander of the I Field Force. As such, he was responsible for the military operations and pacification projects in a vast area beginning eighty miles north of Saigon and extending north for two hundred and twenty miles.

Peers and his assistants, who eventually included two New York lawyers, began working in late November, 1969, and they soon determined that they could not adequately explore the coverup of the atrocity without learning more about what had actually happened on the day the troops were at My Lai 4. On December 2, 1969, the investigating team began interrogating officers and enlisted men in each of the units involved—Charlie Company, Task Force Barker, the 11th Brigade, and the Americal Division. In all, four hundred witnesses were interrogated—about fifty in South Vietnam and the rest in a special-operations room in the basement of the Pentagon—before Peers and a panel of military officers and civilians that varied in size from three to eight men. The interrogations inevitably produced much self-serving testimony. To get at the truth, the Peers commission recalled many witnesses for further interviews and confronted them with testimony that conflicted with theirs. Only six witnesses who appeared before the commission refused to testify, although all could legally have remained silent; perhaps one reason that Peers got such coöperation is that the majority of the witnesses were career military men, and few career military men can afford to seem to be hiding something before a three-star general.

By March 16, 1970, when the investigation ended, the Peers commission had compiled enough evidence to recommend to Secretary of the Army Stanley R. Resor and Army Chief of Staff William C. Westmoreland that charges be filed against fifteen officers; a high-level review subsequently conducted by lawyers representing the office of the Judge Advocate General, the Army’s legal adviser, concluded that fourteen of the fifteen should be charged, including Major General Samuel W. Koster, who was commanding general of the Americal Division at the time of My Lai 4. By then, Koster had become Superintendent of the United States Military Academy, at West Point, and the filing of charges against him stunned the Army. One other general was charged, as were three colonels, two lieutenant colonels, three majors, and four captains. Army officials revealed shortly after the charges were filed that the Peers commission had accumulated more than twenty thousand pages of testimony and more than five hundred documents during fifteen weeks of operation. The testimony and other material alone, it was said, included thirty-two books of direct transcripts, six books of supplemental documents and affidavits, and volumes of maps, charts, exhibits, and internal documents. Defense Department spokesmen explained that, to avoid damaging pre-trial publicity, none of this material could be released to the public until the legal proceedings against the accused men were completed, and officials acknowledged that the process might take years. In addition, it was explained, when the materials were released they would have to be carefully censored, to insure that no material damaging to America’s foreign policy or national security was made available to other countries. In May, 1971, fourteen months after the initial Peers report, officials were still saying that “it might be years” before the investigation was made public. By then, charges against thirteen of the fourteen initial defendants had been dismissed without a court-martial.

Over the past eighteen months, I have been provided with a complete transcript of the testimony given to the Peers Inquiry, and also with volumes of other materials the Peers commission assembled, including its final summary report to Secretary Resor and General Westmoreland. What follows is based largely on those papers, although I have supplemented them with documents from various sources, including the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division, which had the main responsibility for conducting the initial investigations into both the My Lai 4 massacre and its coverup. In addition, I interviewed scores of military and civilian officials, including some men who had been witnesses before the Peers commission and some who might have been called to testify but were not. I also discussed some of my findings with former members of the Army who had been directly connected with the Peers commission.

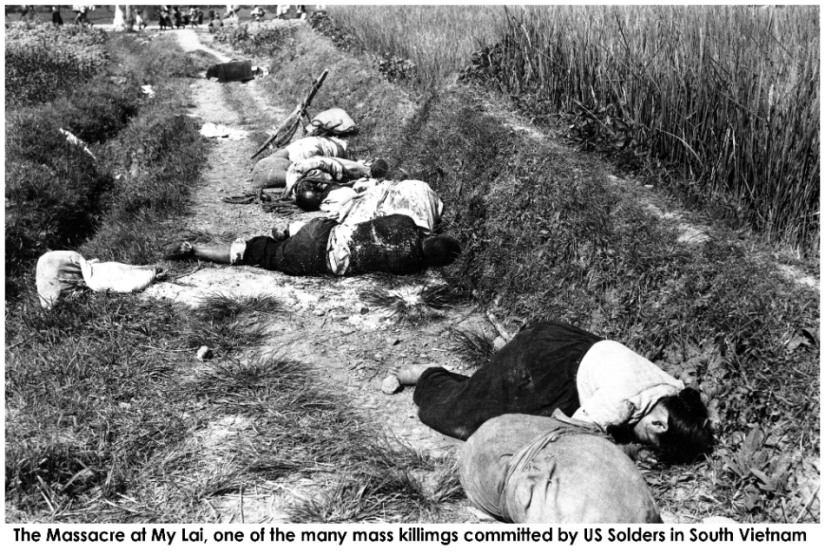

Unquestionably, a serious concern for the rights of possible court-martial defendants does exist at all levels of the Army. A careful examination of the testimony and documents accumulated by the Peers commission makes equally clear that military officials have deliberately withheld from the public important but embarrassing factual information about My Lai 4. For example, the Army has steadfastly refused to reveal how many civilians were killed by Charlie Company on March 16th—a decision that no longer has anything to do with pre-trial publicity, since the last court-martial (that of Colonel Oran K. Henderson, the commanding officer of the 11th Brigade) has been concluded. Army spokesmen have insisted that the information is not available. Yet in February, 1970, the Criminal Investigation Division, at the request of the Peers commission, secretly undertook a census of civilian casualties at My Lai 4 and concluded that Charlie Company had slain three hundred and forty-seven Vietnamese men, women, and children in My Lai 4 on March 16, 1968—a total twice as large as had been publicly acknowledged. In addition, the Peers commission subsequently concluded that Lieutenant Calley’s first platoon, one of three that made the attack upon My Lai 4, was responsible for ninety to a hundred and thirty murders during the operation—roughly one-third of the total casualties, as determined by the C.I.D. The second platoon apparently murdered as many as a hundred civilians, with the rest of the deaths attributable to the third platoon and the helicopter gunships. Despite the vast amount of evidence indicating that the murders at My Lai 4 were widespread throughout the company, only Calley was found guilty of any crime in connection with the attack. Eleven other men and officers were eventually charged with murder, maiming, or assault with intent to commit murder, but the charges were dropped before trial in seven cases and four men were acquitted after military courts-martial. In addition, of the fourteen officers accused by the Peers commission in connection with the coverup only Colonel Henderson was brought to trial. Even more striking was evidence that the attack on My Lai 4 was not the only massacre carried out by American troops in Quang Ngai Province that morning. The Army Investigators learned that Task Force Barker had committed three infantry companies to the over-all operation in the My Lai area. Alpha Company had moved into a blocking position above My Lai 4, where it would theoretically be able to trap Vietcong soldiers as they fled from the Charlie Company assault on the hamlet. Bravo Company, the third unit in the task force, was ordered to attack a possible Vietcong headquarters area at My Lai 1, a hamlet about a mile and a half northeast of My Lai 4. The men of Bravo Company were also told to prepare for a major battle with an experienced Vietcong unit. But, as the Peers commission later learned, there were no Vietcong at My Lai 1, either.

Bravo Company was told about the planned assault on My Lai 1 at a briefing on the night of March 15th. The men of Task Force Barker were called together by their officers that night and told (so one G.I. recalled), “This is what you’ve been waiting for—search and destroy—and you got it.” Captain Earl R. Michles, the company commander, outlined the mission and its objective to his artillery forward observer, the platoon leaders, and other selected members of his command group. The key target, he said, was My Lai 1, a small, often attacked hamlet that was thought to be the headquarters and hospital area of the Vietcong 48th Battalion. Army maps showed that My Lai 1 and the neighboring hamlets of My Lai 2, My Lai 3, and My Lai 4 were part of the village of Son My—a heavily populated area, embracing dozens of hamlets, that was known to the G.I.s as Pinkville, because Son My’s high population density caused it to appear in red on Army maps. To the Americans who operated in the area, Pinkville meant Vietcong guerrillas and booby traps. More than ninety per cent of the Americal Division’s combat injuries and deaths in early 1968 resulted from Vietcong booby traps and land mines. Bravo Company was to be flown into the area by helicopter to engage the Vietcong at My Lai 1, and was then to move south into other supposed Vietcong hamlets along the South China Sea. Precisely what information Michles and his platoon leaders gave their men is impossible to determine, but their briefings—like a similar briefing by Captain Ernest L. Medina, the commander of Charlie Company, at another Task Force Barker fire base, a few miles away—left the soldiers with the impression that everyone they would see on March 16th was sure to be either a Vietcong soldier or a sympathizer.

Michles’s radio operator, Specialist Fourth Class Lawrence L. Congleton, recalled that after the briefing “there was a general conception that we were going to destroy everything.” Only a few of more than forty former Bravo Company G.I.s who were interviewed by members of the Peers commission or who talked with me recalled hearing a specific order to kill civilians. Larry G. Holmes, who was a private first class at the time of the operation, summed up the recollections of many G.I.s when he told the commission, “We had three hamlets that we had to search and destroy. They told us they . . . had dropped leaflets and stuff and everybody was supposed to be gone. Nobody was supposed to be there. If anybody is there, shoot them.” No specific instructions were given about civilians and prisoners, the men told the commission. “We were to leave nothing standing, because we were pretty sure that this was a confirmed V.C. village,” former Private First Class Homer C. Hall testified. One ex-G.I., Barry P. Marshall, told the Peers commission that he had overheard a conversation between Lieutenant Colonel Frank A. Barker, Jr., the commander of the task force, and Michles (both of whom were killed in a helicopter crash three months after the operation). “I don’t want to give the idea that Colonel Barker wanted us to kill every blankety-blank person in here,” Marshall said. “They were just talking. . . . Colonel Barker was just saying that he wished he could get in here and get rid of the V.C. . . . I know Captain Michles’s own personal feeling was that he wanted to take every civilian out of there and move them out of the area to a secure place, and then go in and fight the V.C. It’s so hard, when you’ve got all these people milling around in there, to really conduct an operation of any significance.”

On the morning of the assault, nine troop-transport helicopters, accompanied by two gunships, began ferrying the men of Charlie Company from their assembly point, at Landing Zone Dottie. From Dottie, which also was the site of the task-force headquarters area, the helicopters ferried the men about seven miles southeast to their target area, just outside My Lai 4. The helicopters completed that task by 7:47 A.M., according to the official task-force journal for the day, and then flew a few miles north to Bravo Company’s assembly point to begin shuttling the men of Bravo Company to My Lai 1 for the second stage of the assault. It is not clear why Charlie Company’s assault took place first. Large numbers of Vietcong were thought to be in both hamlets, and, according to the official rationale for the mission, surprise was a key factor. As it was, the first elements of Bravo Company did not reach their target area until 8:15 A.M., and it then took twelve minutes for the full company to assemble. The men were apprehensive, and nothing at their target area soothed them. As they jumped off the aircraft, their rifles at the ready, they heard gunfire in the distance.