The End of the World (as we know it)

ENVIRONMENT, 26 Jul 2021

Dewi Zarni | Medium - TRANSCEND Media Service

“It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

— Frederic Jameson

18 Dec 2020 – Halfway through my final year of college, it has become increasingly difficult to avoid thinking about the future. The prospect of having a career, a family, even growing old one day seems entirely fictional, something attainable for someone at some point in history, but not for me. Instead, I find it easier to picture familiar apocalyptic scenes composed of orange skies, burning forests, flooding, and human displacement.

My mom says that I’m being a pessimist, and she’s probably right. Maybe every generation feels this way at some point, that the scale of the obstacles we face is unprecedented and insurmountable, that we are the ones who get to witness the end. However, anxiety about the future is a defining characteristic of Gen Z. Our generation has the highest rates of loneliness, depression, and suicide, in addition to emerging phenomena such as climate anxiety and eco-grief.

In many ways, depression is a natural response to the circumstances. My childhood was fundamentally shaped by protests, school projects on global warming, and dinnertime conversations about rising sea levels. Our generation is the first to grow up at a time when the existence of climate change is no longer the subject of debate. We are also the last with any chance of mitigating its effects.

The anxiety that so often overwhelms me comes not from understanding the threat of the climate crisis, but from watching those in power repeatedly fail to take action. Growing up involved reconciling the knowledge that our future was in peril and the reality that this fact alone was not enough to create change. Many in our generation quickly learned that in the eyes of the government our lives hold less value than the stock market.

We are constantly reminded of this fact, as guns remain unregulated after countless school shootings, restaurants reopen amid a deadly pandemic that disproportionately affects Black and brown Americans, and the climate crisis — the devastating effects of which we are already seeing — is deemed too expensive to address. As is often the case, disenfranchised groups bear the least responsibility for these crises, yet experience the worst of their effects.

Weeks ago, when CNN finally called the election, I held no false hope that a new president would save us. The harm of another Trump administration would be irreversible and devastating, and his removal from power is cause for celebration, but while Biden’s promise of a return to normal will likely be celebrated over mimosas at many brunches, it is also a promise to ignore the real, life-threatening issues which existed long before Trump took office. As a young person of color, the daughter of an asylee, and a soon-to-be college grad, a return to normal means the continued failure to meaningfully address climate change, the militarization of our borders, student debt, and police violence.

As per usual, centrist Democrats were quick to accuse progressives of harming their image, rather than reflect on their own uninspiring platforms and lackluster campaign efforts, or the potential down-ballot impact of a strategy of appealing to disaffected Republicans. Months before his inauguration, Biden’s opposition to the structural changes necessary to save millions from eviction, poverty, and death, is already clear. He has joined Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi, John Kasich, and numerous media outlets in blaming the movement to defund the police for the Democrats’ losses in the House. According to a leaked call this week, president-elect Biden told leaders from the NAACP and other prominent racial justice and civil rights organizations:

“That’s how they beat the living hell out of us across the country, saying that we’re talking about defunding the police. We’re not. We’re talking about holding them accountable. We’re talking about giving them money to do the right things. We’re talking about putting more psychologists and psychiatrists on the telephones when the 911 calls through. We’re talking about spending money to enable them to do their jobs better, not with more force, with less force and more understanding.”

This diatribe was not prompted by suggestions that Biden defund or even reform the police, but by NAACP President Derrick Johnson’s comment that appointing Tom Vilsack, who is hated by many Georgia farmers, as Secretary of Agriculture could hurt the Democrats’ chances in the upcoming Senate race. Not only were Biden’s claims used to deflect from legitimate concern, but they are also unsubstantiated. Calls to defund the police following George Floyd’s murder and the protests it catalyzed actually coincided with an enormous increase in voter registration for the Democrats. Cori Bush, Ilhan Omar, and Rashida Tlaib all supported defunding the police and faced high profile attacks, but won their elections resoundingly.

More importantly, in distancing themselves from calls to defund the police, Democrats once again legitimize Republican narratives while offering no compelling vision for voters. Republicans consistently label democratic candidates as socialist and attach them to “radical” policies. What if, instead of condemning these policies, which would have a positive impact on our lives, Democrats championed them? If we asked people to imagine the impact of investing millions of dollars in their city’s school system, public transportation, and healthcare, rather than police departments?

Slogans like “defund the police” are not generated through focus groups, they are demands made by activists based on the recognition of their community’s needs. Furthermore, their approval ratings are not fixed. Support for Black Lives Matter, for example, has increased significantly in the past few years. Activists create change by influencing public opinion, not by only championing causes that already have majority support. Already, defunding the police, like other once-unthinkable demands, is gaining popularity, and influencing policies in cities like Minneapolis and Los Angeles. Talking about these radical policies and what they actually mean helps people realize that alternatives to our violent police system are possible.

While I hoped that Biden might recognize the role that progressives and working-class people of color played in his election, his proposed cabinet picks appear to share his commitment to the status quo. They include Neera Tanden, head of the Center for American Progress and a staunch proponent of social security cuts; Rahm Emanuel, the former Chicago mayor who covered up the murder of Laquan McDonald by his police department; Ernest Moniz, a former Obama appointee with deep ties and loyalty to the fossil fuel sector; and two former executives at Blackrock, the world’s largest asset management company.

That Biden’s administration will better reflect the country’s racial and gender makeup means little if its policies continue to harm the majority of Americans. Young, working-class, Black, brown, and Indigenous people turned out in historic numbers to demand change this November. Instead of enacting the progressive changes that have widespread support, such as the Green New Deal, Medicare-for-all, and student debt forgiveness, Biden seems poised to repeat Obama’s presidency by furthering US imperialism, bailing out corporations, and failing to improve the lives of working people.

But it is not 2008. Twelve years have passed, during which time both residents of the White House consistently chose profits over our future. We already have more oil in reserves than we can burn without destroying the planet. 3,000 people are dying from covid every day — parents, grandparents, health care, and service workers who might still be with us had the government followed the lead of those countries providing the resources necessary for their people to stay home. Moderate reforms that will leave millions in debt, unemployed, and without hope for the future will only help another white supremacist rise to power in 2024, promising to deliver a change. With Biden already appealing to conservatives and dismissing the people who elected him, the future feels hopeless.

But neither despair over a coming apocalypse, nor hope that things will return to normal, can save us from the crises we face. Both perspectives reflect a lack of imagination, without which it is easy to feel that we are doomed, or that “normal” is the best we can hope for. The difficulty that so many young people have imagining the future is not coincidental, it is a necessary condition for the survival of neoliberalism. This moment requires that we all expand our notions of what is possible and fight like hell for the best future we can imagine.

In her essay, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Audre Lorde writes that ‘‘[in] a world of possibility for us all, our personal visions help lay the groundwork for political action.” Imagining a better future is the first step toward its creation, but growing up in the United States, conditioned to accept our view of reality as natural, envisioning alternatives is no easy feat. As philosopher and author Martha Nussbaum writes, “One of the greatest barriers to rational deliberation in politics is the unexamined feeling that one’s own preferences and ways are neutral and natural.” By now, most of us can easily recognize the flaws in our elementary school history curriculum. But the process of unlearning the falsehoods we are taught goes beyond recognizing that Columbus did not discover the United States and that our “founding fathers” enslaved their own children. Much harder is acknowledging the ways in which our imagination has been constrained, accepting that our way of looking at the world is not neutral, but fundamentally shaped by a need to maintain the status quo.

Racial capitalism in the United States relies upon the consent of a population unable to imagine (and demand) alternatives. We are taught to accept that inequality and injustice are inevitable, but history shows that this is not necessarily the case.

Today, for example, over two million people are incarcerated in U.S. detention facilities, and we hold more than 20% of the world’s prison population.¹ While life without prisons is impossible for many to imagine, at one point their eradication was the subject of mainstream discourse. In the 1970s, Michelle Alexander writes, most criminologists predicted the end of the prison system, which had proven ineffective at deterring crime. In 1973, The National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals recommended that “no new institutions for adults should be built and existing institutions for juveniles should be closed.”² According to the commission, “the prison, the reformatory and the jail have achieved only a shocking record of failure. There is overwhelming evidence that these institutions create crime rather than prevent it.” But just as prison populations and crime rates began to decline, policies such as the three-strikes law expanded criminalization, while politicians and the media helped justify incarceration.

The right of the U.S. to enforce its borders is also considered common sense. But for much of U.S. history, borders were relatively unregulated. It was not until the 1882 Chinese Immigration Act, 100 years after the country’s independence, that the United States implemented any limits on immigration. Customs and Border Protection was established in 1924, but for decades, movement between the United States and Mexico was largely unrestricted — and even encouraged through policies such as the Bracero Program.

This propensity of humans to forget the past and censor their own imagination enabled Margaret Thatcher to convince a population that “there is no alternative” to neoliberalism. The sentiment of this slogan is embodied by the Democratic party today, which has long relied upon being perceived as the lesser of two evils. Although capitalism and democracy ostensibly promote choice, a rejection of the options we are made to choose from is considered an attack on the system. As Astra Taylor writes, “In a world where the ideology of no alternative continues to rule, any attempt to force a real choice will likely be regarded as a democratic crisis, not a legitimate democratic challenge.”³

But given the crises we face, we now have no choice but to imagine alternatives. We must distinguish between political and physical reality, rejecting excuses based on partisanship or budget deficit that would stand in the way of change. We are so often told that reparations, Medicare-for-all, a Green New Deal, and debt forgiveness are too expensive, while the government consistently finds trillions of dollars for the Pentagon, corporate tax breaks, and subsidies for the very fossil fuel corporations endangering our future. However, the price of a Just Transition off fossil fuels, which would safeguard the interest of workers and the communities most harmed by environmental racism, is negligible compared to the alternative. It is increasingly clear that the continued drudgery of normal life under capitalism is unsustainable, its expiration date nearing. So while it is difficult to imagine an ideal future, it is even harder for me to picture a world in which our current idea of normal, with growing inequality, escalating climate disasters, and eroding democracy continues for another generation.

Left: Toa Baja, Puerto Rico, one year after Hurricane Maria. Center: A house burns during the Australian wildfires, declared one of the “worst wildlife disasters in modern history.” Right: Displaced by genocide, Rohingya refugees in the world’s largest refugee settlement are hit by a record-breaking cyclone.

Thankfully, the work of imagining an alternative does not fall on each of us as individuals. Numerous social movements have provided examples of what the future could look like.

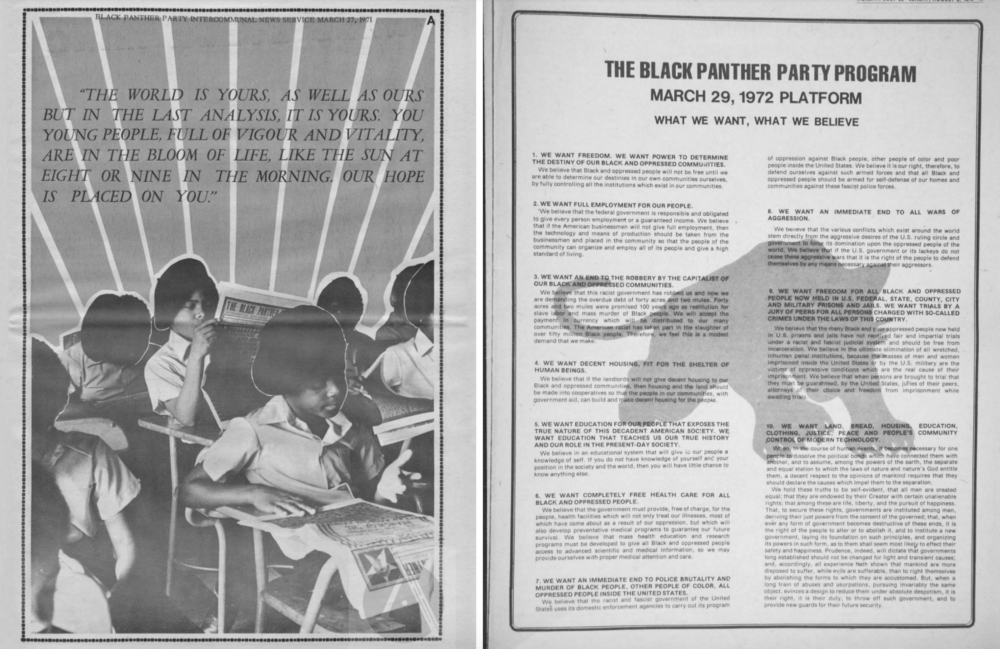

In their Ten-Point Platform, the Black Panther Party laid out their vision of self-determination, housing, employment, and education. Their 65 community survival programs, which included medical, dental, and optometry clinics, free food programs, cooperative housing, and support for prisoners, provided the community with care and resources which the government had withheld. In fulfillment of the 5th point of their platform, The Oakland Community School’s radical curriculum supported the whole child, instilling revolutionary values, the importance of critical thinking, and a sense of Black pride which many students had struggled to maintain in public schools, while also caring for their physical needs with free food and medical programs. Testing revealed that this community-based education was not only possible, but also more effective than traditional methods.

In 1970, The Young Lords, a radical Afro-Latinx movement in New York, seized an x-ray van to provide free services to the community, and later occupied Lincoln Hospital, demanding adequate treatment which had long been denied. In Chiapas, the Zapatistas continue their decades long struggle, reclaiming Indigenous territory and establishing community based schools and medical care.

And this year, Mom’s 4 housing, a collective of houseless mothers founded by Dominique Walker and Sameerah Karim, occupied a vacant home in Oakland for 58 days during their fight against Wedgewood LLC, a home-flipping group (read: gentrifier). The campaign exposed the false narrative of housing shortages in Oakland, where there are 4 times as many empty units as houseless people.

Like any movement which has challenged those in power, these organizations all faced violent state repression. At 5 AM on a January morning, the Oakland Police Department drove a tank into Moms house during a forceful eviction, well aware that the property was home to several young children. The FBI’s COINTELPRO surveilled, imprisoned, and killed numerous members of the Black Panther Party. And a few months ago, the Mexican government finally admitted responsibility for the 1997 massacre of 45 Zapatista supporters who sought shelter in a church, just one incident in a long history of violence against the Indigenous movement.

The state cannot allow these community-based movements to exist, because by providing an example of alternatives to our societal structure, they allow us to imagine large scale change. Just learning of instances in which people have envisioned and created communities of mutual aid is a powerful experience. Doing so has helped me to expand my imagination and my understanding of what is possible. It has given me hope for the future, replacing the images of burning forests and flooded cities with a world I want to be around to see. Unless this imagination is accompanied by action, however, we risk falling into the trap of escapism. Our vision for the future must be a catalyst for change, a weapon which on its own holds little value, but when wielded intentionally by people can topple regimes.

The recognition that our future hinges upon our ability to create massive change is both terrifying and activating. It has compelled young people across the world, from Jerome Foster II, to Mari Copeny, to Autumn Peltier, Vanessa Nakate and so many others, to reject the lie that there is no alternative. While the future is uncertain, it is not doomed. Only by learning about, imagining, and demanding alternatives can we create a future worth experiencing.

As Rebecca Solnit writes, “Hope just means another world might be possible, not promised, not guaranteed. Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope.”

NOTES:

¹ Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York, NY: Seven Stories Press, 2003).

² Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York, NY: New Press, 2012).

³ Astra Taylor, Democracy May Not Exist, but We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone (New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2019).

____________________________________________

Dewi Zarni, born in 1999, is the editor of Secret History of America. Her father, Maung Zarni, is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development, Environment. She is a fourth-year UC Berkeley student majoring in American Studies with a concentration in Migration and was exposed to the complexities of the immigration process and its impact on families through her father’s experience as an asylee from Burma/Myanmar. She volunteered with the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant and was an intern for an immigration attorney where she interviewed Spanish-speaking clients. Dewi is a 2020 BIMI undergraduate research fellow, currently working to gather information on legal and health clinics and to expand the reach of the Mapping Spatial Inequality project.

Dewi Zarni, born in 1999, is the editor of Secret History of America. Her father, Maung Zarni, is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development, Environment. She is a fourth-year UC Berkeley student majoring in American Studies with a concentration in Migration and was exposed to the complexities of the immigration process and its impact on families through her father’s experience as an asylee from Burma/Myanmar. She volunteered with the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant and was an intern for an immigration attorney where she interviewed Spanish-speaking clients. Dewi is a 2020 BIMI undergraduate research fellow, currently working to gather information on legal and health clinics and to expand the reach of the Mapping Spatial Inequality project.

Tags: Capitalism, Climate Change, Conflict, Environment, Global warming, Nature, Solutions

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.