23 Jun 2021 – Every once in a while, a claim comes along that wildly challenges the mainstream scientific narrative. These challenges can occasionally serve as the seed for a revolution in our understanding of some aspect of the world, but much more frequently, the novel claims simply fail to pan out. Oftentimes, the very nature of the claim itself is suspect, and based on a misunderstanding of already known and established facts. Regardless of what’s being claimed, however, we can always anchor ourselves by beginning with a scientifically sound starting point, and then examine the viability of those new claims through that lens.

Recently, Dr. Sherri Tenpenny has claimed that the coronavirus vaccine is actively magnetizing people, stating in her testimony, “I’m sure you’ve seen the pictures all over the internet of people who have had these shots and now they’re magnetized. You can put a key on their forehead, it sticks. You can put spoons and forks all over and they can stick because now we think there is a metal piece to that.”

Fortunately, the science of magnetism has been extraordinarily well-understood for over 150 years. Here’s a look at the science behind this claim.

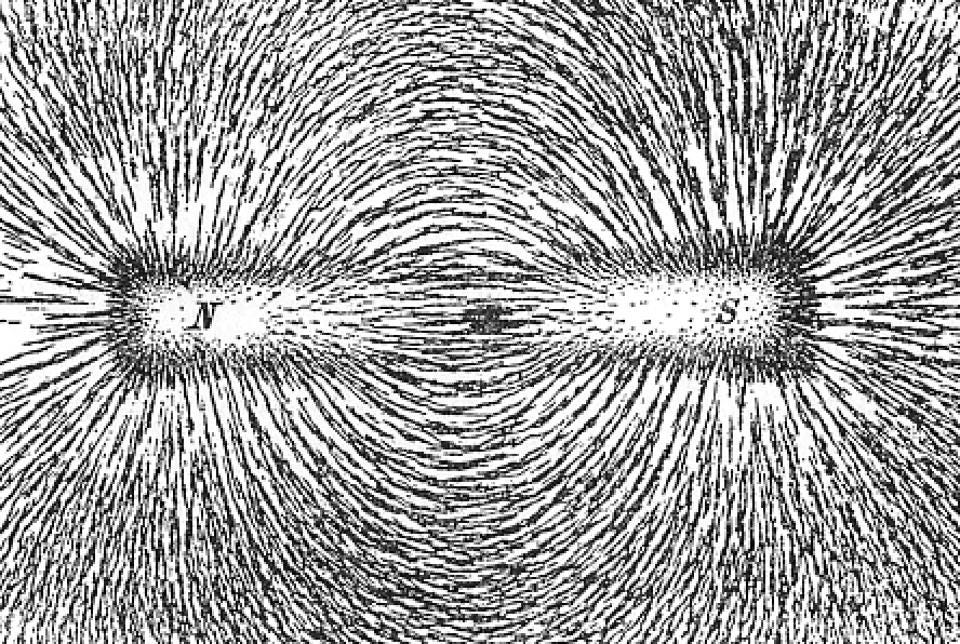

A permanent magnet induces a parallel magnetic field inside certain metals and alloys. Those … [+] getty

Magnetism. Most of us are familiar with permanent magnets, which generate their own magnetic field. When you bring a permanent magnet close to certain materials, the magnet induces a magnetic field inside of those materials, leading to an attractive force. Common examples of this include:

- bringing a permanent magnet close to a refrigerator, upon which it “sticks,”

- bringing a permanent magnet close to a series of paperclips, which can then be picked up by the magnet,

- or using a permanent magnet on the end of a stick to search for any loose metals that may have dropped to the ground.

But this is not how all magnets work; permanent magnets are just one specific type of magnetism at play. All materials that are made of normal matter — atomic nuclei with electrons bound to them — exhibit one or more forms of magnetism, and that includes human beings and everything in them. Of course, there’s an enormous difference between saying “this material exhibits a form of magnetism” and “human beings can be magnetized,” and if we want to answer that latter question, we’d better understand how magnetism itself works.

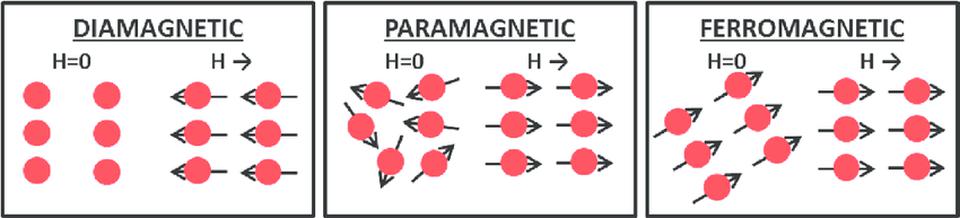

The three types of magnetism that occur in materials are diamagnetism, paramagnetism, and ferromagnetism. Whenever you apply an external magnetic field to a material, you’ll get one of the following three responses.

Diamagnetic: when you place your material into an external magnetic field, the material weakly magnetizes in the opposite direction to the external field, and when you remove the external field, the material completely demagnetizes once again, reverting to its original state.

Paramagnetic: when you place your material into an external magnetic field, it weakly magnetizes parallel to (in the same direction as) the external field, and when you remove the external field, the material demagnetizes and comes out with no internal magnetic field.

Ferromagnetic: when you place your material into an external magnetic field, it strongly magnetizes parallel to the external field, and when the external field is removed, the material may remain partially or even completely magnetized, retaining its own internal magnetic field.

Of these three, only ferromagnetic materials can remain magnetized in the absence of an external field. If we’re talking about “magnetizing” something in a permanent or semi-permanent fashion, we’re always dealing with ferromagnetism.

Magnetic field lines, as illustrated by a bar magnet: a magnetic dipole, with a north and south pole … [+] Newton Henry Black, Harvey N. Davis (1913) Practical Physics

The questions we should be asking, then, are threefold.

- What are the typical magnetic properties of a human body, and is there any substantial ferromagnetism inherent in people that could possibly be exploited or measured?

- What are the ingredients in the specific vaccine in question, as well as in other vaccines more generally, and can they be responsible for magnetizing a human?

- And finally, is there any science behind claims that assert something like, “you can put keys, forks, spoons, etc., all over a human who’s had a coronavirus vaccine, and they’ll stick?”

Let’s begin with the magnetic properties of a human.

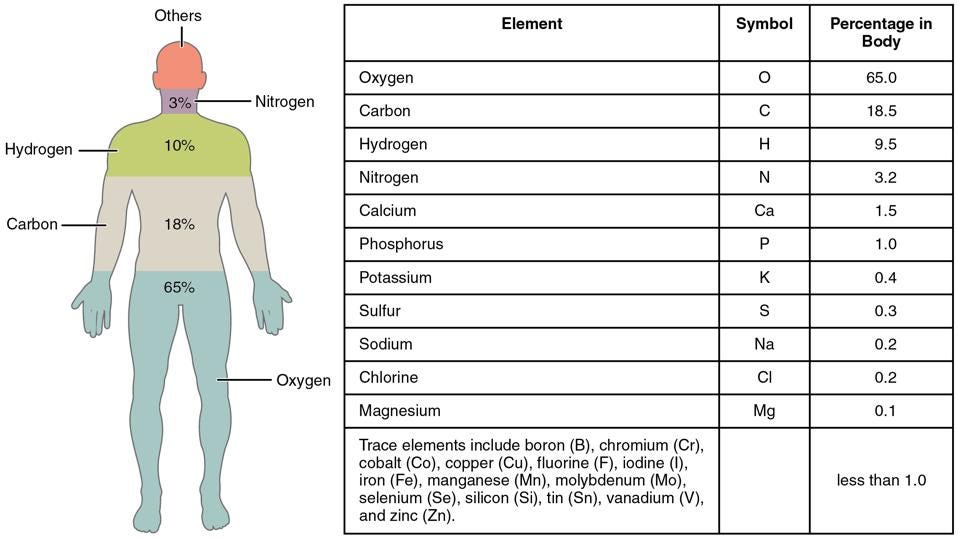

The composition of the human body, as broken down by various elements. While, by mass, we are mostly … [+] Openstax college, Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site

The next most common set of molecules in the human body are lipids: the fats and fatty acids that we store to help meet our energy needs. Lipids are also not ferromagnetic, but can be paramagnetic if certain specific conditions are met.

Proteins, the third most common material, are generally not ferromagnetic in nature, but a 2017 study did discover a magnetic protein, and there is some suspicion that such proteins may be responsible for the sense of magnetoreception in some animals. We can also engineer magnetic protein crystals, but these do not occur in nature.

These three components — water, lipids, and proteins — compose approximately 95% of the human body, typical for many animals. Which effect, overall, dominates? It’s the diamagnetic effects of water, as spectacularly demonstrated by the levitating frog in the video below.

Short clip of a levitating from from Dr. Andre Geim’s lab, circa 1997. The full video can be found … [+] Dr. Andre Geim, Catholic University of Nijmegen/AP

When you apply a very, very strong external magnetic field — the kinds we can only reach with superconducting electromagnets — the induced diamagnetism in water-containing objects will cause the creation of a magnetic field that opposes the external field. If the external field has a “north” pole at the top, then then magnetized frog will have a “north” pole at the bottom, and two north poles will repel each other. If the external field is strong enough, this can even overcome the force of gravity, leading to the phenomenon of magnetic levitation. As it turns out, most biological materials, including human beings, contain large amounts of water and are, overall, weakly diamagnetic.

If you wanted to cause a human being to behave as anything other than diamagnetic — which would repel permanent magnets and experience no forces from non-magnetic materials — you’d have to add in some sort of magnetizable material. You might think, “hey, hemoglobin, found in blood, contains iron, and couldn’t that be ferromagnetic?” But it turns out not to be so; hemoglobin, dependent on whether it’s oxygenated or not, can behave either diamagnetically or paramagnetically, but doesn’t behave ferromagnetically. We’d have to introduce some external agent.

A single dose is drawn from a vial of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine, on March 6, 2021. … [+] Getty Images

What’s in the vaccines? This is the next big question: if human beings, themselves, aren’t permanently magnetizable, could some sort of agent introduced into our bodies suddenly render us capable of being magnetized? And, if so, could any of the vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 contain ingredients that turn our bodies into permanent magnets?

While each of the available vaccines are different from one another, they all have commonalities, too. All vaccines against COVID-19 contain no traces of:

- iron,

- nickel,

- cobalt,

- lithium,

- or rare earth alloys,

as well as lacking (the more conspiratorial) microchips, microelectronics, graphene, nanowires, or electrodes.

Instead, the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, which are mRNA vaccines, contain mRNA, lipids, salts, sugars, as well as (in the case of Moderna) acids and acid stabilizers. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine, on the other hand, contains a modified version of the common cold virus, as well as acids, salts, sugars, and ethanol.

None of these ingredients are magnetic, and — as the CDC notes — even if they were, the size of the vaccine dose is insufficiently small to cause magnets to stick to even the injection site directly.

If a person can easily attach smooth objects to their skin, there’s a good chance that one or more … [+] getty

Magnets and metals stick to human skin. And yet, there are copious examples, including a significant number of recent viral videos, where people are sticking metallic, magnetic, or other objects to their skin, directly, while simultaneously claiming that it’s the coronavirus vaccine that made this “magnetism” possible.

There actually is a kernel of truth in here: many people can, legitimately, “stick” metallic, magnetic, or other objects — including glass, porcelain, plastics, wood, brass, and aluminum — to their skin. Although people who can do so are sometimes colloquially referred to as “human magnets,” with many making claims that they are, in fact, magnetic, the phenomenon at play here is much more mundane than magnetism.

Instead, the reason objects can stick to certain people is the main reason that practically any two objects might refuse to slide off of one another: the force of friction.

Brenda Allison, a so-called human magnet, can easily stick smooth objects to her skin. However, … [+] Brenda Allison / CCA-SA-4.0

- if you try to measure the magnetic field around the person, you achieve a null result; no detectable field above the background of Earth’s intrinsic magnetic field,

- the same people who can stick metallic or magnetic objects to their bodies can stick non-metallic and/or non-ferromagnetic metals to their bodies just as easily,

- that the “sticking” only occurs where the skin is smooth and hairless,

- that the subject is often either leaning back or sticking an object to themselves at less than a 90° angle,

- and — as demonstrated by the late skeptic and magician James Randi — their claimed magnetic powers suddenly disappear if you cover their skin in talc.

Much like the phenomenon of balancing an egg upright during the equinox, which can be done equally well during any day of the year, metal objects can often stick to human skin. But neither magnetism nor vaccine ingredients of any type plays a role at all.

This 2015 photo shows ‘magnetic boy’ Elvir Silayciya, 13, of Kakanj, Bosnia and Herzegovina, as he … [+] Getty Images

It’s true that some people have stickier skin than others, and are quite capable of temporarily attaching massive, macroscopic metallic or magnetic objects to their bare skin. But it isn’t because they’re magnetic; the human body generates and possesses no measurable magnetic fields on its own. It isn’t because you got the coronavirus vaccine; there are no magnetic or magnetizable ingredients in any of them, and the stickiness properties of human skin are unchanged by the vaccines, even at the injection site.

The crux of these claims — that the coronavirus vaccines can transform human bodies into magnets — is demonstrably false. All COVID-19 vaccines contain no magnetic or magnetizable ingredients, they don’t cause magnetism in humans, and moreover, magnetism in humans isn’t even a real, measurable phenomenon. This is simply two unrelated phenomena, the natural stickiness of human skin and the fact that many people have recently gotten a coronavirus vaccine, that have been incorrectly conflated together. If you feel the need to prove it to anyone who claims to be magnetized themselves, simply put some talcum powder on their skin and watch their so-called magnetism spontaneously disappear.