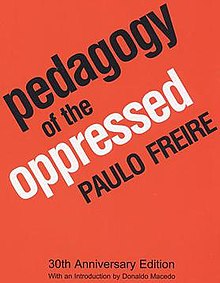

Frei Betto Pays Homage to Paulo Freire on His Birth Centenary: 19 Sep 2021

SPOTLIGHT, 20 Sep 2021

Leonardo Boff - TRANSCEND Media Service

19 Sep 2021 – Frei Betto is one of the best experts on Paulo Freire. Besides being a personal friend, he applied his method in popular education, which he practices until today. This homage to him on the 100th anniversary of his birth is a mixture of experiences lived with him and a simple and exemplary exposition of his method. I join him in this celebration. I met him when Paul was part of the scientific committee of the group of theologians and philosophers that edited and still edits the International Journal Concilium (in 7 languages). Right at the beginning there was a great dialogue, of which he was a master. He is counted among the founders of Liberation Theology, something he said with honor. Here is Frei Betto’s lucid and experiential text.

— Leonardo Boff

************************************************************************

I can say, without fear of exaggeration, that Paulo Freire is the root of the history of Brazilian popular power in the 50 years between 1966 and 2016. This power emerged, like a leafy tree, from the Brazilian left active in the second half of the 20th century: groups that fought against the military dictatorship (1964-1985); the Ecclesial Base Communities of the Christian Churches; the comprehensive network of popular and social movements that emerged in the 1970s; combative trade unionism; and, in the 1980s, the founding of the CUT (Central Única dos Trabalhadores); of ANAMPOS (Articulação Nacional dos Movimentos Populares e Sindicais) and, later, of CMP (Central de Movimentos Populares); of PT (Partidos dos Trabalhadores); and of MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra); and of so many other movements, NGOs, and entities.

If I had to respond to the suggestion, “Name one person who is the cause of all this.” I would say, without any doubt: Paulo Freire. Without Paulo Freire’s methodology of popular education, these movements would not exist, because he taught us something very important: to see history from the oppressed’s point of view and make them protagonists of the changes in society.

The excluded as political subjects

When I came out of political prison at the end of 1973, I had the impression that all the struggle out here had ended because of the repression of the military dictatorship, even because all of us, imbued with the pretension of being the only ones who understood the struggle capable of recovering democracy, were in jail, dead, or in exile. What was my surprise to find a huge network of popular movements spread all over Brazil.

When the PT was founded, in 1980, I saw fellow leftists reacting: “Workers? No. It is too pretentious for workers to want to be the vanguard of the proletariat! It is us, theoretical intellectuals, Marxists, who have the capacity to lead the working class. However, in Brazil the oppressed were beginning to become not only historical subjects, but also political leaders, thanks to the

Paulo Freire’s method

Once, in Mexico, some leftist comrades asked me:

– How do we do something here similar to your process there in Brazil? Because you have a leftist sector in the Church, a combative unionism, the PT… How do you obtain this popular political force?

– Start doing popular education,” I answered, “and in thirty years…

They interrupted me:

– Thirty years is a lot! We want a suggestion for three years.

– For three years I don’t know how to do it,” I observed, “but for thirty years I know the way.

In summary, the whole process of accumulation of popular political forces, which resulted in the election of Lula as president of Brazil, in 2002, and kept the PT in the federal government for thirteen years, did not fall from the sky. Everything was built with a lot of tenacity from the organization and mobilization of popular bases through the application of the Paulo Freire method.

The Paulo Freire method

I first met the Paulo Freire method in 1963. I lived in Rio de Janeiro and was a member of the national direction of the Catholic Action. When the first working groups of the Paulo Freire method emerged, I joined a team that, on Saturdays, went up to Petrópolis, 70km away from Rio, to teach literacy to the workers of the National Motor Factory. There I discovered that nobody teaches anybody anything, some help others to learn.

What did we do with the workers of that truck factory? We photographed the facilities, gathered the workers in a church hall, projected slides and asked them a very simple question:

– In this picture, what didn’t you guys do?

– Well, we didn’t do the tree, the woods, the road, the water…

– That what you didn’t do is nature – we said.

– And what did human work do? – we asked.

– Human labor made the brick, the factory, the bridge, the fence…

– That is culture,” we said. – And how were these things made?

They debated and answered:

– They were made as human beings transformed nature into culture.

Then a picture appeared of the courtyard of the National Motor Factory occupied by many trucks and the workers’ bicycles. We simply asked:

– In this photo, what have you made?

– The trucks.

– And what do you have?

– The bicycles.

– Wouldn’t you be wrong?

– No, we make the trucks…

– And why don’t you go home by truck? Why do you go by bicycle?

– Because the truck costs a lot of money, and it doesn’t belong to us.

– How much does a truck cost?

– About 40 thousand dollars.

– How much do you earn per month?

– Well, we earn an average of $200.

– How long does each one of you have to work, without eating, without drinking, without paying rent, saving all your salary to one day own the truck you make?

Then they began to calculate and became aware of the essence of the capital vs. labor relationship, what is surplus value, exploitation, etc.

The most elementary notions of Marxism, as a critique of capitalism, came through the Paulo Freire method. The difference was that we were not teaching a class, we were not doing what Paulo Freire called “banking education”, that is, putting political notions into the worker’s head. The method was inductive. As Paulo said, we teachers did not teach, but helped the students to learn.

Distinct and complementary cultures

When I arrived in São Bernardo do Campo (SP) in 1980, there were leftist militants who distributed newspapers among the workers’ families. One day Ms. Marta asked me

– What is “crasse contradiction”?

– Doña Marta, forget it.

– I’m not much of a reader,” she justified, “because my eyesight is poor and my handwriting is small.

– Forget it,” I said. – The left writes these texts for themselves to read and be happy, thinking that they are making a revolution.

Paulo Freire taught us not only to speak in popular, plastic, not academically conceptual language, but also to learn from the people. He taught the people to recover their self-esteem.

When I got out of prison, I lived for five years in a slum in Espírito Santo. There I worked with popular education using the Paulo Freire method. When I returned to São Paulo at the end of the 1970s, Paulo Freire proposed that I write an account of our experience in education and, thanks to the mediation of journalist Ricardo Kotscho, we produced a book called “Essa escola chamada vida” (Ática). It is his account as educator and creator of the method, and of my experience as a basic educator.

In the book, I tell that in the slum where I lived there was a group of women pregnant with their first child, assisted by doctors from the Municipal Health Secretariat. I asked the doctors why we should work only with women who were pregnant with their first child.

– We don’t want women who already have maternal addictions. – they said – We want to teach them everything.

Well, a few months later, there was a knock at the door of my shack.

– Betto, we want your help.

– My help?

– There is a short circuit between us and the women. They don’t understand what we say. You, who have experience with these people, could advise us.

I went to see their work. When I entered the slum’s Health Center, I was scared. There were very poor women there, and the center had been decorated with posters of Johnson babies, little blondes with blue eyes, Nestle advertisements, and so on. At this sight, I reacted:

– It’s all wrong. When the women come here and look at these babies, they realize that this is another world, it has nothing to do with the babies on the hill.

I watched the work of the doctors. I noticed that they were talking on FM and the women were tuned into AM. The communication really didn’t work. In one session, Dr. Raul explained, in scientific language, the importance of breastfeeding, and therefore of proteins, for the formation of the human brain. When he finished his presentation, the women stared at him as I do when I open a text in Mandarin or Arabic: I don’t understand anything.

– Do you understand what Dr. Raul said? – I asked.

– No, I didn’t understand, I only understood that he said that our milk is good for the children’s heads.

– And why didn’t you understand?

– Because I am uneducated. I didn’t go to school much, I was born poor in the countryside. I had to work with a hoe and help support the family.

– And why was Dr. Raul able to explain all this?

– Because he is a doctor, he is studied. He knows and I don’t know.

– Dr. Raul, can you cook? – I asked.

– I don’t even know how to make coffee.

– Mrs. Maria, can you cook?

– Yes, I can.

– Can you make chicken “ao molho pardo” (a dish that, in Espirito Santo, and also in some areas of the Northeast, is called “galinha de cabidela”)?

– Yes.

– Please, stand up – I asked – and tell us how to make a frango ao molho pardo.

Dona Maria gave us a cooking lesson: how to kill the chicken, which side to remove the feathers, how to prepare the meat and make the sauce, etc.

When she sat down, I said

– Dr. Raul, do you know how to make a dish like this?

– No way, I like it, but I don’t know how to cook.

– Mrs. Maria,” I concluded, “you and Dr. Raul, both lost in a closed forest, hungry, and suddenly a chicken appears. He, with all his culture, would die of hunger, but not you.

The woman grinned from ear to ear. She discovered, at that moment, a fundamental principle of Paulo Freire: there is no one more cultured than another, there are distinct cultures, socially complementary. If we weigh all my philosophy and theology and the cooking of the cook at the convent where I live, she can do without my knowledge, but I cannot do without her culture. Here is the difference. The culture of a cook is indispensable for all of us

Paulo Freire and Future Challenges

Facing the emergence of so many authoritarian governments and the profusion of antidemocratic, racist, homophobic, sexist, and negationist messages in digital networks, it seems to me of utmost importance to revisit Paulo Freire on this date of the centennial of his birth.

The ebb of progressive forces in Latin America in recent years, and the emergence of neo-fascist figures like Bolsonaro in Brazil, force us to recognize that for decades we have abandoned the grassroots work of popular organization and mobilization. This void with the populations of the periphery, of the slums, of the poor rural areas, has been occupied by religious fundamentalism, drug trafficking, and militia.

In his works, Paulo Freire teaches us that there is no mobilization without prior awareness. It is necessary that people have a “clothesline” on which to hang their political concepts and the keys to analyze reality. The “clothesline” is the perception of time as history.

There are civilizations, tribes, groups, that have no perception of time as history. The ancient Greeks, for example, believed that time is cyclical. Today, cyclical time returns through esotericism, negationism, fatalism, and religious fundamentalism. But it returns, above all, through neoliberalism.

The essence of neoliberalism is the dehistoricization of time. When Fukuyama declared that “ahistory is over,” he expressed what neoliberalism wants to instill in us: We have reached the fullness of time! The neoliberal capitalist mode of production, based on the supremacy of the market, is final! Few are the chosen, and many are the excluded. And it is no longer enough to want to fight for an alternative society, for “another possible world”!

In fact, nowadays it is difficult to talk about an alternative society. Socialism, no way! A shame has been created, an intellectual and emotional block. “The alternatives that are put forward are, in general, intrasystemic.

The notion that time is history comes from the Persians, passed on to the Hebrews and accentuated by the Jewish tradition. Three great paradigms of our culture are of Jewish origin – Jesus, Marx and Freud – and, therefore, worked with the category of time as history.

One cannot study Marxism without delving into the previous modes of production, to understand how the capitalist mode of production was arrived at. And then to understand how its contradictions could lead to socialist and communist modes of production. Marxist analysis presupposes, therefore, the rescue of time as history.

If someone is undergoing analysis or therapy, the psychoanalyst soon asks the patient about his past, his childhood, his upbringing. If the patient can talk about his intrauterine life, so much the better. Freud’s whole psychology is a rescue of our temporality as individuals.

Jesus’ perspective was historical. The God of Jesus presents himself with curriculum vitae: he is not just any god – he is the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – that is, a God who makes history. The main category of Jesus’ preaching is historical: the Kingdom of God. Although placed up there by ecclesiastical discourse, theologically it is not located up there. The Kingdom is something up ahead, it is the culmination of the historical process..

. It is curious that in the Bible history, as a factor that identifies time, is so strong that in the Genesis account the Creation of the world is already marked by this historicity of time before the appearance of human beings.

For many, history is what men and women do. So, there would be no history before the appearance of men and women, so much so that they speak of prehistory. For the Bible, there is already history before the appearance of the human being. So much so that the Greeks considered the god of the Hebrews to be a very incompetent entity. A true god creates like Nescafé: instant, and not in time, as the biblical account shows. Now, in the Creation story, in seven days, there is already historicity. And Paulo Freire, a man of Christian background and a militant supporter of the foundations of Marxism, knew how to perceive the importance of reading the world as a condition for reading the text.

Neoliberalism does not suit this perspective. Therefore, one cannot do popular education without having a “clothesline” to hang the clothes… This “clothesline” – time as history – is fundamental to visualize the social and political process. This also happens in the micro dimension of our lives. Why, today, do many people find it difficult to have life projects? Why do young people reach the age of 20 without the slightest idea of what they want to be or do with their lives? For many of them, everything is here and now.

Therefore, if we want to rescue Paulo Freire’s legacy, the way is to return to the grassroots work with the popular classes, adopting his method in a historical perspective, open to libertarian utopias and democratic horizons. Outside the people there is no salvation. And if we believe that democracy must be, in fact, the government of the people for the people and with the people, there is no alternative but to adopt the Paulo Freirean educational process that places the oppressed as political and historical protagonists.

When Paulo Freire returned from 15 years of exile, in August 1979, we met in São Paulo. We were neighbors and I often visited him. We had very close personal relationships.

My personal testimony

So I end this tribute with this text that I wrote on May 2, 1997, the date of Paulo Freire’s transvivencation:

“Ivo saw the grape,” the literacy manuals taught. But Professor Paulo Freire, with his method of teaching literacy by raising awareness, made adults and children, in Brazil and Guinea-Bissau, in India, in Nicaragua, and in so many other places, discover that Ivo did not only see with his eyes. He also saw with his mind and asked himself if grapes are nature or culture.

Ivo saw that fruit is not the result of human work. It is Creation, it is nature. Paulo Freire taught Ivo that sowing grapes is human action in and on nature. And the hand, a multi-tool, awakens the potentialities of the fruit. Just as the human being himself was sowed by nature in years and years of evolution of the Universe.

To pick the grapes, crush them, and turn them into wine is culture, Paulo Freire pointed out. Work humanizes nature and, by doing it, men and women humanize themselves. Work establishes the knot of relationships, social life. Thanks to the professor, who started his revolutionary pedagogy with Sesi workers in Pernambuco, Ivo also saw that grapes are harvested by labourers, who earn little, and commercialized by middlemen, who earn much more.

Ivo learned from Paulo that, even without knowing how to read, he is not an ignorant person. Before learning how to read, Ivo knew how to build a house, brick by brick. The doctor, the lawyer or the dentist, with all his study, is not able to build like Ivo. Paulo Freire taught Ivo that there is no one more cultured than another, there are parallel, distinct cultures that complement each other in social life.

Ivo saw the grape and Paulo Freire showed him the bunches, the vine, the whole plantation. He taught Ivo that the reading of a text is better understood the more the text is inserted in the context of the author and the reader. It is from this dialogical relationship between text and context that Ivo draws the pretext for action. At the beginning and end of learning, it is Ivo’s praxis that matters. Praxis-theory-practice, in an inductive process that makes the learner a historical subject.

Ivo saw the grape and did not see the bird that, from above, sees the vine and does not see the grape. What Ivo sees is different from what the bird sees. Thus, Paulo Freire taught Ivo a fundamental principle of epistemology: the head thinks where the feet step. The unequal world can be read from the oppressor’s perspective or from the oppressed’s perspective. The result is a reading as different from one another as between Ptolemy’s vision, when observing the solar system with his feet on the Earth, and Copernicus’ vision, when imagining himself with his feet on the Sun.

It is curious that in the Bible history, as a factor that identifies time, is so strong that in the Genesis account the Creation of the world is already marked by this historicity of time before the appearance of human beings.

For many, history is what men and women do. So, there would be no history before the appearance of men and women, so much so that they speak of prehistory. For the Bible, there is already history before the appearance of the human being. So much so that the Greeks considered the god of the Hebrews to be a very incompetent entity. A true god creates like Nescafé: instant, and not in time, as the biblical account shows. Now, in the Creation story, in seven days, there is already historicity. And Paulo Freire, a man of Christian background and a militant supporter of the foundations of Marxism, knew how to perceive the importance of reading the world as a condition for reading the text.

Neoliberalism does not suit this perspective. Therefore, one cannot do popular education without having a “clothesline” to hang the clothes… This “clothesline” – time as history – is fundamental to visualize the social and political process. This also happens in the micro dimension of our lives. Why, today, do many people find it difficult to have life projects? Why do young people reach the age of 20 without the slightest idea of what they want to be or do with their lives? For many of them, everything is here and now.

Therefore, if we want to rescue Paulo Freire’s legacy, the way is to return to the grassroots work with the popular classes, adopting his method in a historical perspective, open to libertarian utopias and democratic horizons. Outside the people there is no salvation. And if we believe that democracy must be, in fact, the government of the people for the people and with the people, there is no alternative but to adopt the Paulo Freirean educational process that places the oppressed as political and historical protagonists.

When Paulo Freire returned from 15 years of exile, in August 1979, we met in São Paulo. We were neighbors and I often visited him. We had very close personal relationships.

So I end this tribute with this text that I wrote on May 2, 1997, the date of Paulo Freire’s transvivencation:

“Ivo saw the grape,” the literacy manuals taught. But Professor Paulo Freire, with his method of teaching literacy by raising awareness, made adults and children, in Brazil and Guinea-Bissau, in India, in Nicaragua, and in so many other places, discover that Ivo did not only see with his eyes. He also saw with his mind and asked himself if grapes are nature or culture.

Ivo saw that fruit is not the result of human work. It is Creation, it is nature. Paulo Freire taught Ivo that sowing grapes is human action in and on nature. And the hand, a multi-tool, awakens the potentialities of the fruit. Just as the human being himself was sowed by nature in years and years of evolution of the Universe.

To pick the grapes, crush them, and turn them into wine is culture, Paulo Freire pointed out. Work humanizes nature and, by doing it, men and women humanize themselves. Work establishes the knot of relationships, social life. Thanks to the professor, who started his revolutionary pedagogy with Sesi workers in Pernambuco, Ivo also saw that grapes are harvested by labourers, who earn little, and commercialized by middlemen, who earn much more.

Ivo learned from Paulo that, even without knowing how to read, he is not an ignorant person. Before learning how to read, Ivo knew how to build a house, brick by brick. The doctor, the lawyer or the dentist, with all his study, is not able to build like Ivo. Paulo Freire taught Ivo that there is no one more cultured than another, there are parallel, distinct cultures that complement each other in social life.

Ivo saw the grape and Paulo Freire showed him the bunches, the vine, the whole plantation. He taught Ivo that the reading of a text is better understood the more the text is inserted in the context of the author and the reader. It is from this dialogical relationship between text and context that Ivo draws the pretext for action. At the beginning and end of learning, it is Ivo’s praxis that matters. Praxis-theory-practice, in an inductive process that makes the learner a historical subject.

Ivo saw the grape and did not see the bird that, from above, sees the vine and does not see the grape. What Ivo sees is different from what the bird sees. Thus, Paulo Freire taught Ivo a fundamental principle of epistemology: the head thinks where the feet step. The unequal world can be read from the oppressor’s perspective or from the oppressed’s perspective. The result is a reading as different from one another as between Ptolemy’s vision, when observing the solar system with his feet on the Earth, and Copernicus’ vision, when imagining himself with his feet on the Sun.

Now Ivo sees the grape, the grapevine and all the social relationships that make the fruit a feast in the cup of wine, but he no longer sees Paulo Freire, who plunged into Love on the morning of May 2, 1997. He leaves us a priceless work and an admirable testimony of competence and coherence.

Paulo should have been in Cuba to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Havana. Sensing the pain in his heart that he loved so much, he asked me to represent him. I was scheduled to fly to Palestine, but was unable to attend. However, before leaving, I went to pray with Nita, his wife, and their children, around his peaceful countenance: Paulo saw God.

________________________________________________

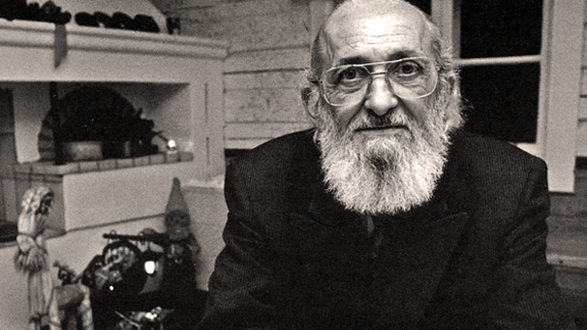

Paulo Freire [19 Sep 1921 – 2 May 1997] was born in Recife, Brazil. In 1947 he began work with adult illiterates in North-East Brazil and gradually evolved a method of work with which the word conscientization has been associated. Until 1964 he was Professor of History and Philosophy of Education in the University of Recife and in the 1960s he was involved with a popular education movement to deal with massive illiteracy. From 1962 there were widespread experiments with his method and the movement was extended under the patronage of the federal government. In 1963-4 there were courses for coordinators in all Brazilian states and a plan was drawn up for the establishment of 2000 cultural circles to reach 2,000,000 illiterates! Freire was imprisoned following the 1964 coup d’état for what the new regime considered to be subversive elements in his teaching. He next appeared in exile in Chile where his method was used and the UN School of Political Sciences held seminars on his work. In 1969-70 he was Visiting Professor at the Centre for the Study of Development and Social Change at Harvard University. He then went to the World Council of Churches in Geneva where, in 1970, he took up a post as special consultant in the Office of Education. Over the next nine years in that post he advised on education reform and initiated popular education activities with a range of groups. Paulo Freire was able to return to Brazil by 1979. He joined the Workers’ Party in Sao Paulo and headed up its adult literacy project for six years. When the party took control of Sao Paulo municipality following elections in 1988, Paulo Freire was appointed as Sao Paulo’s Secretary of Education.

Paulo Freire [19 Sep 1921 – 2 May 1997] was born in Recife, Brazil. In 1947 he began work with adult illiterates in North-East Brazil and gradually evolved a method of work with which the word conscientization has been associated. Until 1964 he was Professor of History and Philosophy of Education in the University of Recife and in the 1960s he was involved with a popular education movement to deal with massive illiteracy. From 1962 there were widespread experiments with his method and the movement was extended under the patronage of the federal government. In 1963-4 there were courses for coordinators in all Brazilian states and a plan was drawn up for the establishment of 2000 cultural circles to reach 2,000,000 illiterates! Freire was imprisoned following the 1964 coup d’état for what the new regime considered to be subversive elements in his teaching. He next appeared in exile in Chile where his method was used and the UN School of Political Sciences held seminars on his work. In 1969-70 he was Visiting Professor at the Centre for the Study of Development and Social Change at Harvard University. He then went to the World Council of Churches in Geneva where, in 1970, he took up a post as special consultant in the Office of Education. Over the next nine years in that post he advised on education reform and initiated popular education activities with a range of groups. Paulo Freire was able to return to Brazil by 1979. He joined the Workers’ Party in Sao Paulo and headed up its adult literacy project for six years. When the party took control of Sao Paulo municipality following elections in 1988, Paulo Freire was appointed as Sao Paulo’s Secretary of Education.

Frei Betto is a writer, author of Por uma educação crítica e participativa (Rocco) and Essa escola chamada vida (Ática), in partnership with Paulo Freire and Ricardo Kotscho. Virtual bookstore: http://www.freibetto.org

Frei Betto is a writer, author of Por uma educação crítica e participativa (Rocco) and Essa escola chamada vida (Ática), in partnership with Paulo Freire and Ricardo Kotscho. Virtual bookstore: http://www.freibetto.org

Leonardo Boff is a Brazilian theologian, ecologist, writer and university professor exponent of the Liberation Theology. He is a former friar, member of the Franciscan Order, respected for his advocacy of social causes and environmental issues. Boff is a founding member of the Earthcharter Commission.

Leonardo Boff is a Brazilian theologian, ecologist, writer and university professor exponent of the Liberation Theology. He is a former friar, member of the Franciscan Order, respected for his advocacy of social causes and environmental issues. Boff is a founding member of the Earthcharter Commission.

Go to Original – leonardoboff.org

Tags: Activism, Brasil, Brazil, Education, Frei Betto, History, Leonardo Boff, Literacy, Literature, Oppression, Paradigm change, Paulo Freire, Pedagogia do Oprimido, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Praxis

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.