“Eulogy” for James Bond: World Peace Is at Peril

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 11 Oct 2021

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

The Glorious End

1 Oct 2021 – The atmosphere was sombre as “M”[1], the Head of MI6, reads a brief eulogy for his top MI6 agent 007, James Bond[2], with Miss Moneypenny[3], “Q”[4], and Lashana Lynch[5] present in Lieutenant Colonel Gareth Mallory’s[6] (M’s) office, darkened for the occasion. “The proper function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.[7] “James Bond was certainly a man who lived rather than existed and the passage, written by American novelist Jack London, was first published by the San Francisco Bulletin in 1916. The passage later served as the introduction to a compilation of London’s short stories published posthumously in 1956.[8] Ironically, the passage is only part of the longer paragraph: “I would rather be ashes than dust! I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than it should be stifled by dry rot. I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet.[9] The proper function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.”

The poignant remembrance scene concluded with “M” and his team drinking a Vodka Martini shaken, but not stirred to commemorate the death of James Bond to the accompaniment of lilting music by Hans Zimmer[10] and the song “We have all the time in the World”[11]. This is a James Bond movie theme and popular song sung by Louis Daniel Armstrong[12]. The music was composed by John Barry [13]and the lyrics by Hal David. It is a secondary musical theme in the 1969 Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the title theme being the instrumental “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”, also composed by John Barry. The song title is taken from Bond’s final words in both the novel and the film, spoken after the death of Tracy Bond, his wife. Armstrong was too ill to play his trumpet therefore it was played by another musician.[14] Barry chose Armstrong because he felt he could “deliver the title line with irony”.[15] On 6 January 2020, it was announced that Hans Zimmer would be taking over as composer for the Bond 25 film, “No Time to Die”[16] after previous composer Dan Romer[17] left the project.[18]

In the concluding sequences of the film “No Time to Die” James Bond dies a glorious death, in a fiery scene, as multiple missiles incinerate the secret island liar, somewhere between Russia and Japan as well as James Bond, with it. This is where the archvillain of the film, Lyutsifer Safin, played by Rami Malek[19], a worthy adversary of James Bond. Safin sets out on a mission of revenge against Blofeld, who killed his parents, and SPECTRE (Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion)[20] His means of doing so is the Heracles virus, a lethal bioweapon being developed, off the books by MI6[21]. It contains nanobots that spread like a virus upon touch, and are coded to specific DNA strands so that they are only dangerous if programmed to an individual’s genetic code. Safin planned to dominate the world after stealing the targeted nanorobots to eliminate listed individuals. While Safin is not necessarily a physical match for 007, he is nevertheless extremely intelligent, dangerous, and a potent antagonist. He has many elements to his character that both feeds into, and in some cases are at odds with, his nefarious plan.[22] James Bond bravely faces death on the top of the central structure of a missile launcher on the island, after killing the villain Safin, who had already poisoned him with the nanorobots[23].

Thus, at a chronological age of 58 James Bond, after being given birth by the writer Ian Fleming in 1953, Barbara Broccoli and co-producer George Wilson of Eon Productions kill off James Bond at the end of 25th movie, spanning a period from 1965 with the first James Bond movie, “Dr No” to “No Time To Die” on 30th September 2021, after three delayed release dates due to the SARS Cov-2 Pandemic. The South African general public were privileged to view the film in cinemas, in Imax and 3D screens well before the British audiences who will only have the pleasure of seeing the final movie with Daniel Craig on 08th October 2021in UK. The film was only released on the big screen, and not streamed, as the studio chiefs agreed, on worldwide, distribution.

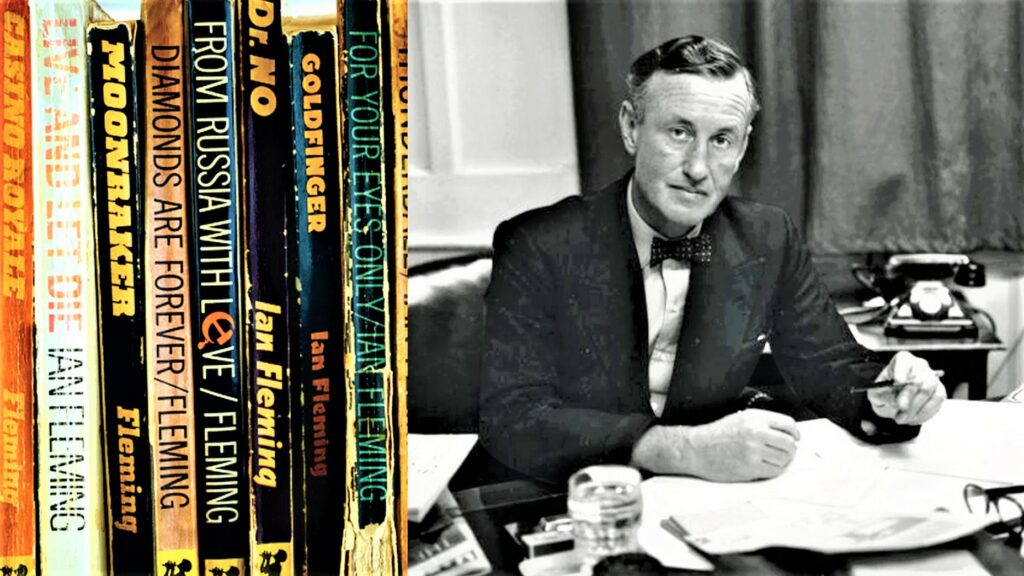

James Bond’s literary father, Ian Lancaster Fleming[24] (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, journalist and naval intelligence officer who is best known for his James Bond series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his father was the Member of Parliament for Henley from 1910 until his death on the Western Front in 1917. Educated at Eton, Sandhurst, and, briefly, the universities of Munich and Geneva, Fleming moved through several jobs before he started writing. While working for Britain’s Naval Intelligence Division during the Second World War, Fleming was involved in planning Operation Goldeneye and in the planning and oversight of two intelligence units, 30 Assault Unit and T-Force. His wartime service and his career as a journalist provided much of the background, detail and depth of the James Bond novels.[25]

Fleming wrote his first Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1952. It was a success, with three print runs being commissioned to cope with the demand. Eleven Bond novels and two collections of short stories followed between 1953 and 1966. The novels revolve around James Bond, an officer in the Secret Intelligence Service, commonly known as MI6. Bond is also known by his code number, 007, and was a commander in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. The Bond stories rank among the best-selling series of fictional books of all time, having sold over 100 million copies worldwide. Fleming also wrote the children’s story Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang and two works of non-fiction. In 2008, The Times ranked Fleming 14th on its list of “The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”.

On a personal note, Fleming was married to Ann Charteris, who was divorced from the second Viscount Rothermere because of her affair with the author. Fleming and Charteris had a son, Caspar. Fleming was a heavy smoker and drinker for most of his life and succumbed to heart disease in 1964 at the age of 56. Two of his James Bond books were published posthumously; other writers have since produced Bond novels. Fleming’s creation has appeared in film 27 times, portrayed by seven different James Bond actors.

Fleming[26] had first mentioned to friends during the war that he wanted to write a spy novel, an ambition he achieved within two months with Casino Royale. He started writing the book at Goldeneye, his residence, on 17th February 1952, gaining inspiration from his own experiences and imagination. He claimed afterwards that he wrote the novel to distract himself from his forthcoming wedding to the pregnant Charteris, and called the work his “dreadful oafish opus”. His manuscript was typed in London by Joan Howe (mother of travel writer Rory MacLean), and Fleming’s red-haired secretary at The Times on whom the character Miss Moneypenny was partially based. Clare Blanchard, a former girlfriend, advised him not to publish the book, or at least to do so under a pseudonym.

During Casino Royale’s final draft stages, Fleming allowed his friend William Plomer to see a copy, and remarked “so far as I can see the element of suspense is completely absent”. Despite this, Plomer thought the book had sufficient promise and sent a copy to the publishing house Jonathan Cape. At first, they were unenthusiastic about the novel, but Fleming’s brother Peter, whose books they managed, persuaded the company to publish it. On 13th April 1953 Casino Royale was released in the UK in hardcover, priced at 10s 6d, with a cover designed by Fleming. It was a success and three print runs were needed to cope with the demand.

The novel centres on the exploits of James Bond, an officer in the Secret Intelligence Service, commonly known as MI6. Bond is also known by his code number, 007, and was a commander in the Royal Naval Reserve. Fleming took the name for his character from that of the American ornithologist James Bond, an expert on Caribbean birds and author of the definitive field guide Birds of the West Indies. Fleming, himself a keen birdwatcher, had a copy of Bond’s guide, and later told the ornithologist’s wife, “that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine name was just what I needed, and so a second James Bond was born”. In a 1962 interview in The New Yorker, he further explained: “When I wrote the first one in 1953, I wanted Bond to be an extremely dull, uninteresting man to whom things happened; I wanted him to be a blunt instrument … when I was casting around for a name for my protagonist I thought by God, [James Bond] is the dullest name I ever heard.”

An illustration was commissioned by Fleming, showing his concept of the James Bond character he created. Fleming based his creation on individuals he met during his time in the Naval Intelligence Division, and admitted that Bond “was a compound of all the secret agents and commando types I met during the war”. Among those types were his brother Peter, whom he worshipped, and who had been involved in behind-the-lines operations in Norway and Greece during the war. Fleming envisaged that Bond would resemble the composer, singer and actor Hoagy Carmichael; others, such as author and historian Ben Macintyre, identify aspects of Fleming’s own looks in his description of Bond. General references in the novels describe Bond as having “dark, rather cruel good looks”.

Fleming also modelled aspects of Bond on Conrad O’Brien-French, a spy whom Fleming had met while skiing in Kitzbühel in the 1930s, Patrick Dalzel-Job, who served with distinction in 30AU during the war, and Bill “Biffy” Dunderdale, station head of MI6 in Paris, who wore cufflinks and handmade suits and was chauffeured around Paris in a Rolls-Royce. Sir Fitzroy Maclean was another possible model for Bond, based on his wartime work behind enemy lines in the Balkans, as was the MI6 double agent Duško Popov. Fleming also endowed Bond with many of his own traits, including the same golf handicap, his taste for scrambled eggs, his love of gambling, and use of the same brand of toiletries.

After the publication of Casino Royale, Fleming used his annual holiday at his house in Jamaica to write another Bond story. Twelve Bond novels and two short-story collections were published between 1953 and 1966, the last two (The Man with the Golden Gun and Octopussy and The Living Daylights) posthumously. Much of the background to the stories came from Fleming’s previous work in the Naval Intelligence Division or from events he knew of from the Cold War. The plot of From Russia, with Love uses a fictional Soviet Spektor decoding machine as a lure to trap Bond; the Spektor had its roots in the wartime German Enigma machine. The novel’s plot device of spies on the Orient Express was based on the story of Eugene Karp, a US naval attaché and intelligence agent based in Budapest who took the Orient Express from Budapest to Paris in February 1950, carrying papers about blown US spy networks in the Eastern Bloc. Soviet assassins already on the train drugged the conductor, and Karp’s body was found shortly afterwards in a railway tunnel south of Salzburg.

Many of the names used in the Bond works came from people Fleming knew: Scaramanga, the principal villain in The Man with the Golden Gun, was named after a fellow Eton schoolboy with whom Fleming fought; Goldfinger, from the eponymous novel, was named after British architect Ernő Goldfinger, whose work Fleming abhorred; Sir Hugo Drax, the antagonist of Moonraker, was named after Fleming’s acquaintance Admiral Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax; Drax’s assistant, Krebs, bears the same name as Hitler’s last Chief of Staff; and one of the homosexual villains from Diamonds Are Forever, “Boofy” Kidd, was named after one of Fleming’s close friends and a relative of his wife Arthur Gore, 8th Earl of Arran, known as Boofy to his friends.

Fleming’s first work of non-fiction, The Diamond Smugglers, was published in 1957 and was partly based on background research for his fourth Bond novel, Diamonds Are Forever. Much of the material had appeared in The Sunday Times and was based on Fleming’s interviews with John Collard, a member of the International Diamond Security Organisation who had previously worked in MI5. The book received mixed reviews in the UK and US.

For the first five books (Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, Moonraker, Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia, with Love) Fleming received broadly positive reviews. That began to change in March 1958 when Bernard Bergonzi, in the journal Twentieth Century, attacked Fleming’s work as containing “a strongly marked streak of voyeurism and sado-masochism” and wrote that the books showed “the total lack of any ethical frame of reference”. The article compared Fleming unfavourably with John Buchan and Raymond Chandler on both moral and literary criteria. A month later, Dr. No was published, and Fleming received harsh criticism from reviewers who, in the words of Ben Macintyre, “rounded on Fleming, almost as a pack”. The most strongly worded of the critiques came from Paul Johnson of the New Statesman, who, in his review “Sex, Snobbery and Sadism”, called the novel “without doubt, the nastiest book I have ever read”. Johnson went on to say that “by the time I was a third of the way through, I had to suppress a strong impulse to throw the thing away”. Johnson recognised that in Bond there “was a social phenomenon of some importance”, but this was seen as a negative element, as the phenomenon concerned “three basic ingredients in Dr No, all unhealthy, all thoroughly English: the sadism of a schoolboy bully, the mechanical, two-dimensional sex-longings of a frustrated adolescent, and the crude, snob-cravings of a suburban adult.” Johnson saw no positives in Dr. No, and said, “Mr Fleming has no literary skill, the construction of the book is chaotic, and entire incidents and situations are inserted, and then forgotten, in a haphazard manner.”

Lycett notes that Fleming “went into a personal and creative decline” after marital problems and the attacks on his work. Goldfinger had been written before the publication of Dr. No; the next book Fleming produced after the criticism was For Your Eyes Only, a collection of short stories derived from outlines written for a television series that did not come to fruition. Lycett noted that, as Fleming was writing the television scripts and the short stories, “Ian’s mood of weariness and self-doubt was beginning to affect his writing”, which can be seen in Bond’s thoughts.

In 1960 Fleming was commissioned by the Kuwait Oil Company to write a book on the country and its oil industry. The Kuwaiti government disapproved of the typescript, State of Excitement: Impressions of Kuwait, and it was never published. According to Fleming: “The Oil Company expressed approval of the book but felt it their duty to submit the typescript to members of the Kuwait Government for their approval. The Sheikhs concerned found unpalatable certain mild comments and criticisms and particularly the passages referring to the adventurous past of the country which now wishes to be ‘civilised’ in every respect and forget its romantic origins.”

Fleming followed the disappointment of For Your Eyes Only with Thunderball, the novelisation of a film script on which he had worked with others. The work had started in 1958 when Fleming’s friend Ivar Bryce introduced him to a young Irish writer and director, Kevin McClory, and the three, together with Fleming and Bryce’s friend Ernest Cuneo, worked on a script. In October McClory introduced experienced screenwriter Jack Whittingham to the newly formed team, and by December 1959 McClory and Whittingham sent Fleming a script. Fleming had been having second thoughts on McClory’s involvement and, in January 1960, explained his intention of delivering the screenplay to MCA, with a recommendation from him and Bryce that McClory act as producer. He additionally, told McClory that if MCA rejected the film because of McClory’s involvement, then McClory should either sell himself to MCA, back out of the deal, or file a suit in court.

Working at Goldeneye between January and March 1960, Fleming wrote the novel Thunderball, based on the screenplay written by himself, Whittingham and McClory. In March 1961 McClory read an advance copy, and he and Whittingham immediately petitioned the High Court in London for an injunction to stop publication. After two court actions, the second in November 1961, Fleming offered McClory a deal, settling out of court. McClory gained the literary and film rights for the screenplay, while Fleming was given the rights to the novel, provided it was acknowledged as “based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and the Author”.

Fleming’s books had always sold well, but in 1961 sales increased dramatically. On 17th March 1961, four years after its publication and three years after the heavy criticism of Dr. No, an article in Life listed From Russia, with Love as one of US President John F. Kennedy’s 10 favourite books. Kennedy and Fleming had previously met in Washington. This accolade and the associated publicity led to a surge in sales that made Fleming the biggest-selling crime writer in the US. Fleming considered From Russia, with Love to be his best novel; he said “the great thing is that each one of the books seems to have been a favourite with one or other section of the public and none has yet been completely damned.”

In April 1961, shortly before the second court case on Thunderball, Fleming had a heart attack during a regular weekly meeting at The Sunday Times. While he was convalescing, one of his friends, Duff Dunbar, gave him a copy of Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and suggested that he take the time to write up the bedtime story that Fleming used to tell to his son Caspar each evening. Fleming attacked the project with gusto and wrote to his publisher, Michael Howard of Jonathan Cape, joking that “There is not a moment, even on the edge of the tomb, when I am not slaving for you”; the result was Fleming’s only children’s novel, Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, which was published in October 1964, two months after his death.

In June 1961 Fleming sold a six-month option on the film rights to his published and future James Bond novels and short stories to Harry Saltzman. Saltzman formed the production vehicle Eon Productions along with Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli, and after an extensive search, they hired Sean Connery on a six-film deal, later reduced to five beginning with Dr. No (1962). Connery’s depiction of Bond affected the literary character; in You Only Live Twice, the first book written after Dr. No was released, Fleming gave Bond a sense of humour that was not present in the previous stories. Fleming’s second non-fiction book was published in November 1963: Thrilling Cities, a reprint of a series of Sunday Times articles based on Fleming’s impressions of world cities in trips taken during 1959 and 1960. Approached in 1964 by producer Norman Felton to write a spy series for television, Fleming provided several ideas, including the names of characters Napoleon Solo and April Dancer, for the series The Man from U.N.C.L.E. However, Fleming withdrew from the project following a request from Eon Productions, who were keen to avoid any legal problems that might occur if the project overlapped with the Bond films. In January 1964 Fleming went to Goldeneye for what proved to be his last holiday and wrote the first draft of The Man with the Golden Gun. He was dissatisfied with it and wrote to William Plomer, the copy editor of his novels, asking for it to be rewritten. Fleming became increasingly unhappy with the book and considered rewriting it, but was dissuaded by Plomer, who considered it viable for publication.

Fleming was a heavy smoker and drinker throughout his adult life, and suffered from heart disease. In 1961, aged 53, he suffered a heart attack and struggled to recuperate. On 11th August 1964, while staying at a hotel in Canterbury, Fleming went to the Royal St George’s Golf Club for lunch and later dined at his hotel with friends. The day had been tiring for him, and he collapsed with another heart attack shortly after the meal. Fleming died at age 56 at Kent and Canterbury Hospital in the early morning of 12th August 1964, on his son Caspar’s 12th birthday. His last recorded words were an apology to the ambulance drivers for having inconvenienced them, saying “I am sorry to trouble you chaps. I don’t know how you get along so fast with the traffic on the roads these days.” Fleming was buried in the churchyard of Sevenhampton, near Swindon. Presently, an obelisk marks the site of the Fleming family grave and memorial, at Sevenhampton, Wiltshire. His will was proved on 4th November, with his estate valued at £302,147 (equivalent to £6,168,011 in 2019.

Fleming’s last three books, The Man with the Golden Gun, Octopussy and The Living Daylights, were published posthumously. The Man with the Golden Gun was published eight months after Fleming’s death and had not been through the full editing process by Fleming. As a result, the novel was thought by publishing company Jonathan Cape to be thin and “feeble”. The publishers had passed the manuscript to Kingsley Amis to read on holiday, but did not use his suggestions. Fleming’s biographer Henry Chandler observes that the novel “received polite and rather sad reviews, recognising that the book had effectively been left half-finished, and as such did not represent Fleming at the top of his game”. The final Bond book, containing two short stories, Octopussy and The Living Daylights, was published in Britain on 23 June 1966. In October 1975 Fleming’s son Caspar, aged 23, committed suicide by drug overdose and was buried with his father. Fleming’s widow, Ann, died in 1981 and was buried with her husband and their son.

The author Raymond Benson, who later wrote a series of Bond novels, noted that Fleming’s books fall into two stylistic periods. Those books written between 1953 and 1960 tend to concentrate on “mood, character development, and plot advancement”, while those released between 1961 and 1966 incorporate more detail and imagery. Benson argues that Fleming had become “a master storyteller” by the time he wrote Thunderball in 1961.

Jeremy Black divides the series based on the villains Fleming created, a division supported by fellow academic Christoph Lindner. Thus the early books from Casino Royale to For Your Eyes Only are classed as “Cold War stories”, with SMERSH[27] as the antagonists. These were followed by Ernst Stavro Blofeld and SPECTRE as Bond’s opponents in the three novels Thunderball, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and You Only Live Twice, after the thawing of East–West relations. Black and Lindner classify the remaining books; The Man with the Golden Gun, Octopussy and The Living Daylights and The Spy Who Loved Me as “the later Fleming stories”.

Fleming said of his work, “while thrillers may not be Literature with a capital L, it is possible to write what I can best describe as ‘thrillers designed to be read as literature'”. He named Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Eric Ambler and Graham Greene as influences. William Cook in the New Statesman considered James Bond to be “the culmination of an important but much-maligned tradition in English literature. As a boy, Fleming devoured the Bulldog Drummond tales of Lieutenant Colonel H. C. McNeile (aka “Sapper”) and the Richard Hannay stories of John Buchan. His genius was to repackage these antiquated adventures to fit the fashion of postwar Britain. In Bond, he created a Bulldog Drummond for the jet age.” Umberto Eco considered Mickey Spillane to have been another major influence.

In May 1963 Fleming wrote a piece for Books and Bookmen magazine in which he described his approach to writing Bond books: “I write for about three hours in the morning … and I do another hour’s work between six and seven in the evening. I never correct anything and I never go back to see what I have written … By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day.” Benson identified what he described as the “Fleming Sweep”, the use of “hooks” at the end of chapters to heighten tension and pull the reader into the next. The hooks combine with what Anthony Burgess calls “a heightened journalistic style” to produce “a speed of narrative, which hustles the reader past each danger point of mockery”.

Umberto Eco analysed Fleming’s works from a Structuralist point of view, and identified a series of oppositions within the storylines that provide structure and narrative, including:-

Bond—M

Bond—Villain

Villain—Woman

Woman—Bond

Free World—Soviet Union

Great Britain—Non-Anglo-Saxon Countries

Duty—Sacrifice

Cupidity—Ideals

Love—Death

Chance—Planning

Luxury—Discomfort

Excess—Moderation

Perversion—Innocence

Loyalty—Dishonour

Eco also noted that the Bond villains tend to come from Central Europe or from Slavic or Mediterranean countries and have a mixed heritage and “complex and obscure origins”. Eco found that the villains were generally asexual or homosexual, inventive, organisationally astute, and wealthy. Black observed the same point: “Fleming did not use class enemies for his villains instead relying on physical distortion or ethnic identity … Furthermore, in Britain foreign villains used foreign servants and employees … This racism reflected not only a pronounced theme of interwar adventure writing, such as the novels of Buchan, but also wider literary culture.” Writer Louise Welsh found that the novel Live and Let Die “taps into the paranoia that some sectors of white society were feeling” as the civil rights movements challenged prejudice and inequality.

Fleming used well-known brand names and everyday details to support a sense of realism. Kingsley Amis called this “the Fleming effect”, describing it as “the imaginative use of information, whereby the pervading fantastic nature of Bond’s world … [is] bolted down to some sort of reality, or at least counter-balanced.” Major themes in Fleming’s novels included Britain’s position in the world, from a colonial legacy. The Bond books were written in post-war Britain, when the country was still an imperial power. As the series progressed, the British Empire was in decline; journalist William Cook observed that “Bond pandered to Britain’s inflated and increasingly insecure self-image, flattering us with the fantasy that Britannia could still punch above her weight.” This decline of British power was referred to in several of the novels; in From Russia, with Love, it manifested itself in Bond’s conversations with Darko Kerim, when Bond admits that in England, “we don’t show teeth any morem only gums.” The theme is strongest in one of the later books of the series, the 1964 novel You Only Live Twice, in conversations between Bond and the Head of Japan’s secret intelligence service, Tiger Tanaka. Fleming was acutely aware of the loss of British prestige in the 1950s and early 60s, particularly during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, when he had Tanaka accuse Britain of throwing away the empire “with both hands”.

Black points to the defections of four members of MI6 to the Soviet Union as having a major impact on how Britain was viewed in US intelligence circles. The last of the defections was that of Kim Philby in January 1963, while Fleming was still writing the first draft of You Only Live Twice. The briefing between Bond and M is the first time in the twelve books that Fleming acknowledges the defections. Black contends that the conversation between M and Bond allows Fleming to discuss the decline of Britain, with the defections and the Profumo affair of 1963 as a backdrop. Two of the defections had taken place shortly before Fleming wrote Casino Royale, and the book can be seen as the writer’s “attempt to reflect the disturbing moral ambiguity of a post-war world that could produce traitors like Burgess and Maclean”, according to Lycett.

By the end of the series, in the 1965 novel, The Man with the Golden Gun, Black notes that an independent inquiry was undertaken by the Jamaican judiciary, while the CIA and MI6 were recorded as acting “under the closest liaison and direction of the Jamaican CID”: this was the new world of a non-colonial, independent Jamaica, further underlining the decline of the British Empire. The decline was also reflected in Bond’s use of US equipment and personnel in several novels. Uncertain and shifting geopolitics led Fleming to replace the Russian organisation SMERSH with the international terrorist group SPECTRE in Thunderball, permitting “evil unconstrained by ideology”. Black argues that SPECTRE provides a measure of continuity to the remaining stories in the series.

A theme throughout the Bond novel series was the effect of the Second World War. The Times journalist Ben Macintyre considers that Bond was “the ideal antidote to Britain’s postwar austerity, rationing and the looming premonition of lost power”, at a time when coal and many items of food were still rationed. Fleming often used the war as a signal to establish good or evil in characters: in For Your Eyes Only, the villain, Hammerstein, is a former Gestapo officer, while the sympathetic Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer, Colonel Johns, served with the British under Montgomery in the Eighth Army. Similarly, in Moonraker, Drax (Graf Hugo von der Drache) is a “megalomaniac German Nazi who masquerades as an English gentleman”, and his assistant, Krebs, bears the same name as Hitler’s last Chief of Staff. In this, Fleming “exploits another British cultural antipathy of the 1950s. Germans, in the wake of the Second World War, made another easy and obvious target for bad press.” As the series progressed, the threat of a re-emergent Germany was overtaken by concerns about the Cold War, and the novels changed their focus accordingly.

Periodically, in the series, the topic of comradeship or friendship arises, with a male ally who works with Bond on his mission. Raymond Benson believes that the relationships Bond has with his allies “add another dimension to Bond’s character, and ultimately, to the thematic continuity of the novels”. In Live and Let Die, agents Quarrel and Leiter represent the importance of male friends and allies, seen especially in Bond’s response to the shark attack on Leiter; Benson observes that “the loyalty Bond feels towards his friends is as strong as his commitment to his job”. In Dr. No, Quarrel is “an indispensable ally”. Benson sees no evidence of discrimination in their relationship and notes Bond’s genuine remorse and sadness at Quarrel’s death. Furthermore, the “traitor within” is a recurring theme from the opening novel in the series, the theme of treachery was strong. Bond’s target in Casino Royale, Le Chiffre, was the paymaster of a French communist trade union, and the overtones of a fifth column struck a chord with the largely British readership, as Communist influence in the trade unions had been an issue in the press and parliament, especially after the defections of Burgess and Maclean in 1951. The “traitor within” theme continued in Live and Let Die and Moonraker, as well as in No Time To Die, causing the demise of his long time friend, Felix Leiter.

There is also the theme of good versus evil pervading the entire series, as considered by Raymond Benson, This crystallised in Goldfinger with the Saint George motif, which is stated explicitly in the book: “Bond sighed wearily. Once more into the breach, dear friend! This time, it really was St George and the dragon. And St George had better get a move on and do something”; Black notes that the image of St. George is an English, rather than British personification.

The Bond novels also dealt with the question of Anglo-American relations, reflecting the central role of the US in the defence of the West. In the aftermath of the Second World War, tensions surfaced between a British government trying to retain its empire and the American desire for a capitalist new world order, but Fleming did not focus on this directly, instead creating “an impression of the normality of British imperial rule and action”. Author and journalist Christopher Hitchens observed that “the central paradox of the classic Bond stories is that, although superficially devoted to the Anglo-American war against communism, they are full of contempt and resentment for America and Americans”. Fleming was aware of this tension between the two countries, but did not focus on it strongly. Kingsley Amis, in his exploration of Bond in The James Bond Dossier, pointed out that “Leiter, such a nonentity as a piece of characterisation … he, the American, takes orders from Bond, the Britisher, and that Bond is constantly doing better than he”.

For three of the novels, Goldfinger, Live and Let Die and Dr. No, it is Bond, the British agent who has to sort out what turns out to be an American problem, and Black points out that although it is American assets that are under threat in Dr. No, a British agent and a British warship, HMS Narvik, are sent with British soldiers to the island at the end of the novel to settle the matter. Fleming became increasingly jaundiced about America, and his comments in the penultimate novel You Only Live Twice reflect this; Bond’s responses to Tanaka’s comments reflect the declining relationship between Britain and America, in sharp contrast to the warm, co-operative relationship between Bond and Leiter in the earlier books.

To remember Ian Fleming and as a legacy, a bronze bust of Fleming by sculptor Anthony Smith was commissioned by the Fleming family in 2008 to commemorate the centenary of the author’s birth. In the late 1950s the author Geoffrey Jenkins had suggested to Fleming that he write a Bond novel set in South Africa, and sent him his own idea for a plot outline which, according to Jenkins, Fleming felt had great potential. After Fleming’s death, Jenkins was commissioned by Bond publishers Glidrose Productions to write a continuation Bond novel, Per Fine Ounce, but it was never published. Starting with Kingsley Amis’s Colonel Sun, under the pseudonym “Robert Markham” in 1968, several authors have been commissioned to write Bond novels, including Sebastian Faulks, who was asked by Ian Fleming Publications to write a new Bond novel in observance of what would have been Fleming’s 100th birthday in 2008.

During his lifetime Fleming sold thirty million books; double that number were sold in the two years following his death. In 2008 The Times ranked Fleming fourteenth on its list of “The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”. In 2002 Ian Fleming Publications announced the launch of the CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger award, presented by the Crime Writers’ Association to the best thriller, adventure or spy novel originally published in the UK.

Cinematically, Eon Productions series of Bond films, brought to life and increased the popularity of the character of James Bond, which Ian Fleming had created. This commenced in 1962 with Dr. No, and continued after Fleming’s death. Along with two non-Eon produced films, there have been 25 Eon films, with the most recent, being No Time To Die, marking the death of the character. The Eon Productions series has grossed over $6.2 billion worldwide, making it one of the highest-grossing film series.

The influence of Bond in the cinema and in literature is evident in films and books including the Austin Powers series, Carry On Spying and the Jason Bourne character. In 2011 Fleming became the first English-language writer to have an international airport named after him: Ian Fleming International Airport, near Oracabessa, Jamaica, was officially opened on 12th January 2011 by Jamaican Prime Minister Bruce Golding and Fleming’s niece, Lucy. The Lilly Library at Indiana University houses a collection of Fleming manuscripts and first editions as well as his personal.

As a fitting contribution to his eulogy, apart from his creator, it is necessary to describe James Bond himself, although a fictional character, who has the largest following of any name in the world. He is heading the list of famous fictional characters created for mass entertainment, not by Hollywood but strangely by the British. James Bond is known in the deepest part of Africa, to the Amazon, by children, adults and geriatrics, alike. He is the persona every man, young, old and elderly likes to be and the dream man of some women. He is on the top of the league of the likes of Superman, Indiana Jones (America’s answer to James Bond), Darth Vader, Captain James Tiberius Kirk, portrayed by William Shatner[28], who incidentally, turned 80 this week, Zorro, and latterly, John Wick, who, over the past three movies has achieved tremendous popularity and following, but not spanning a career on the silver screen since 1962, until Friday, 01st October 2021, when he suffered a cinematic death in South Africa. His personal details were: Spouse: Teresa di Vicenzo (widowed), killed by Ernest Blofeld, Head of Spectre, in a drive by shooting, Parents: Andrew Bond (father) · Monique Delacroix (mother), Nationality: British.

Fleming endowed Bond with many of his own traits, including sharing the same golf handicap, the taste for scrambled eggs and using the same brand of toiletries. Bond’s tastes are also often taken from Fleming’s own, as was his behaviour, with Bond’s love of golf and gambling mirroring Fleming’s own. Fleming used his experiences of his espionage career and all other aspects of his life as inspiration when writing, including using names of school friends, acquaintances, relatives and lovers throughout his books. It was not until the penultimate novel, You Only Live Twice, that Fleming gave Bond a sense of family background. The book was the first to be written after the release of Dr. No in cinemas and Sean Connery’s depiction of Bond affected Fleming’s interpretation of the character, to give Bond both a sense of humour and Scottish antecedents that were not present in the previous stories. In a fictional obituary, purportedly published in The Times, Bond’s parents were given as Andrew Bond, from the village of Glencoe, Scotland, and Monique Delacroix, from the canton of Vaud, Switzerland. Fleming did not provide Bond’s date of birth, but John Pearson’s fictional biography of Bond, James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007, gives Bond a birth date on 11 November 1920, while a study by John Griswold puts the date at 11 November 1921. James Bond also made forays into television, radio, comics, role playing games and even video games, in his long saga.

Bond was endowed with guns, from a Beretta to Walter PPK, gadgets designed by “Q”, special vehicles, including an amphibious car, as well as the famous Aston Martin DB5 first featured in Goldfinger to the DB 10 in Spectre and cinematically, filmed in many exotic locations. It is interesting to note that the original DB5 made numerous appearances in subsequent movies, including the last one, No Time To Die where the vehicle’s full potential of gadgetry was brought life on the giant Imax and 3D screens in South Africa, at least.

In No Time To Die” Bond’s friend from CIA , the inimitable Felix Leiter also dies a death from a gun shot wound, fired by a traitor. In the course of his career, Bond fought and dispatched many exotic villains such as Colonel Rosa Klebb, with her poisoned tipped shoe, Odd Job with his lethal, steel brimmed hat, Jaws, and other formidable foes complementing the principal villains at each outing. Regarding his attire, the first few movies saw Bond dressed in Saville Row suits, followed by Brioni[29] and then the dressings became more casual, although Bond wears a black, three-piece Tom Ford suit in Spectre. As he aged, the flirtations with traditional Bond girls became scarce. Bond was briefly married, previously and shortly widowed thereafter, He developed a serious relationship with Dr. Madeleine Swann, until his death, with the five-year-old girl, Mathilde, featured in No Time to Die is Bond’s progeny, highlighting his emotional side in the final movie.

No eulogy would be complete without a mention of the orchestral rendition and composition of the traditional musical score, as a background to the opening and now hallmark of all Eon Production, Bond movies. This is the innovative view through the gun barrel. The original score for the “James Bond Theme” was written by Monty Norman and was first orchestrated by the John Barry Orchestra for 1962’s Dr. No. The actual authorship of the music has been a matter of controversy for many years. In 2001, Norman won £30,000 in libel damages from The Sunday Times newspaper, which suggested that Barry was entirely responsible for the composition. The theme, as written by Norman and arranged by Barry, was described by another Bond film composer, David Arnold, as “bebop-swing vibe coupled with that vicious, dark, distorted electric guitar, definitely an instrument of rock ‘n’ roll … it represented everything about the character you would want: It was cocky, swaggering, confident, dark, dangerous, suggestive, sexy, unstoppable. And he did it in two minutes.” Barry composed the scores for eleven Bond films and had an uncredited contribution to Dr. No with his arrangement of the Bond Theme.

A Bond film staple are the theme songs heard during their title sequences sung by well-known popular singers. Several of the songs produced for the films have been nominated for Academy Awards for Original Song, including Paul McCartney’s “Live and Let Die”, Carly Simon’s “Nobody Does It Better”, Sheena Easton’s “For Your Eyes Only”, Adele’s “Skyfall”, and Sam Smith’s “Writing’s on the Wall”. Adele won the award at the 85th Academy Awards, and Smith won at the 88th Academy Awards. For the non-Eon produced Casino Royale, Burt Bacharach’s score included “The Look of Love” (sung by Dusty Springfield), which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song.

For the first five novels, Fleming armed Bond with a Beretta 418 until he received a letter from a thirty-one-year-old Bond enthusiast and gun expert, Geoffrey Boothroyd, criticising Fleming’s choice of firearm for Bond, calling it “a lady’s gun and not a very nice lady at that!” Boothroyd suggested that Bond should swap his Beretta for a 7.65mm Walther PPK and this exchange of arms made it to Dr. No. Boothroyd also gave Fleming advice on the Berns-Martin triple draw shoulder holster and a number of the weapons used by SMERSH and other villains. In thanks, Fleming gave the MI6 Armourer in his novels the name Major Boothroyd and, in Dr. No, M introduces him to Bond as “the greatest small-arms expert in the world”. Bond also used a variety of rifles, including the Savage Model 99 in “For Your Eyes Only” and a Winchester.308 target rifle in “The Living Daylights”. Other handguns used by Bond in the Fleming books included the Colt Detective Special and a long-barreled Colt .45 Army Special. The first Bond film, Dr. No, saw M ordering Bond to leave his Beretta behind and take up the Walther PPK, which Bond used in eighteen films. In Tomorrow Never Dies and the two subsequent films, Bond’s main weapon was the Walther P99 semi-automatic pistol.

The James Bond movie franchise was inaugurated by Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman[30] in 1963. Herschel Saltzman known as Harry Saltzman, was a Canadian theatre and film producer, He is best remembered for co-producing the first nine of the James Bond movies[31]. In early 1961, excited by reading the James Bond novel Goldfinger, he made a bid to land the film rights to the character. Saltzman co-founded Danjaq, S.A. with Albert R. Broccoli[32] in 1962. It was a holding company responsible for the copyright and trademarks of James Bond on screen, and the parent company of Eon Productions, which they also set up as a film production company for the Bond films. The moniker Danjaq is a combination of Broccoli’s and Saltzman’s wives’ first names, Dana and Jacqueline.[33] Saltzman would remain Broccoli’s partner up through the ninth film in the series, 1974’s The Man with the Golden Gun, after which Harry Saltzman left the company.[34] Albert Romolo Broccoli, born on April 5th 1909 and died on June 27th 1996, nicknamed “Cubby”, was an American film producer who made more than 40 motion pictures throughout his career. Most of the films were made in the United Kingdom and often filmed at Pinewood Studios. He was the Co-founder of Danjaq, LLC and Eon Productions, Broccoli is most notable as the producer of many of the James Bond films. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman saw the films develop from relatively low-budget origins to large-budget, high-grossing extravaganzas, and Broccoli’s heirs continue to produce new Bond films, presently.[35] Broccoli’s dictum was “throw your money at the big screen”[36] At the beginning of the 1950s, Broccoli moved once more, this time to London, where the British government provided subsidies to film productions made in the UK with British casts and crews. Together with Irving Allen, Broccoli formed Warwick Films, which made a prolific and successful series of films for Columbia Pictures.

When Broccoli became interested in bringing Ian Fleming’s James Bond character into features, he discovered that the rights already belonged to the Canadian producer Harry Saltzman, who had long wanted to break into film, and who had produced several stage plays and films with only modest success. When the two were introduced by a common friend, screenwriter Wolf Mankowitz, Saltzman refused to sell the rights, but agreed to partner with Broccoli and co-produce the films, which led to the creation of the production company EON Productions and its parent (holding) company Danjaq, LLC, named after their two wives’ first names—Dana and Jacqueline.

Saltzman and Broccoli produced the first Bond film, Dr. No, in 1962. Their second, From Russia with Love, was a break-out success and from then on the films grew in cost, action, and ambition. With larger casts, more difficult stunts and special effects, and a continued dependence on exotic locations, the franchise became essentially a full-time job. Broccoli made one notable attempt at a non-Bond film, an adaptation of Ian Fleming’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang in 1968, and due to legal wrangling over the rights to story elements, ceded producer credit on Thunderball to Kevin McClory. Nonetheless, by the mid-1960s, Broccoli had put nearly all of his energies into the Bond series. Saltzman’s interests continued to range apart from the series, including production of a loose trilogy of spy films based on Len Deighton’s Harry Palmer, a character who operates in a parallel universe to Bond, with all the danger but none of the glamour and gadgets. Saltzman and Broccoli had differences over Saltzman’s outside commitments; however, in the end, it was Saltzman who withdrew from Danjaq and EON after a series of financial mishaps. While Saltzman’s departure brought the franchise a step closer to corporate control, Broccoli lost relatively little independence or prestige in the bargain. From then until his death, the racy credits sequence to every EON Bond film would begin with the words “Albert R. Broccoli Presents.” Although from the 1970s onward the films became lighter in tone and looser in plot and, at times, less successful with critics. The series distinguished itself in production values and continued to appeal to audiences.

In 1966, Albert was in Japan with other producers scouting locations to film the next James Bond movie “You Only Live Twice”. Albert had a ticket booked on BOAC Flight 911. He cancelled his ticket on that day so he could see a ninja demonstration. Flight 911 crashed after clear-air turbulence.[37],[38]

Broccoli married three times.[39] In 1959, Broccoli married actress and novelist Dana Wilson (born Dana Natol; January 3, 1922 – February 29, 2004).[40] They had a daughter, Barbara Broccoli. Albert Broccoli became a mentor to Dana’s teenage son, Michael G. Wilson (OBE)[41], is the stepson of Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, and has worked as a producer and or screenwriter on every James Bond film including “No Time To Die”.[42] The children grew up around the Bond film sets, and his wife’s influence on various production decisions is alluded to in many informal accounts.[43] Michael Wilson worked his way up through the production company to co-write and co-produce. Barbara Broccoli, in her turn, served in several capacities under her father’s tutelage from the 1980s onwards Wilson and Barbara Broccoli have co-produced the films since Albert Broccoli’s death.[44] Broccoli made a cameo appearance in Moonraker (1979) as a tourist in Venice with wife Dana Broccoli.[45]

Broccoli died at his home in Beverly Hills in 1996 at the age of 87 of heart failure. He had undergone a triple heart bypass earlier that year. He was interred in an ornate sarcophagus in the outdoor Courts of Remembrance section, at Forest Lawn – Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles following a funeral mass at The Church of the Good Shepherd, Beverly Hills.[46]

In recognition of Broccoli’s insistence that every James Bond film produced by EON should bear the name of the character’s creator, Ian Fleming, in the opening credits (even when the film contained no real connection to any Fleming novel, apart from the titular character), it was decided by his surviving family that all subsequent Bond films should bear Broccoli’s name. Therefore, all Bond films since Tomorrow Never Dies have opened with the line “Albert R. Broccoli’s EON Productions presents”.[47]

In 1995, Barbara’s father Cubby Broccoli handed over control of Eon Productions, the production company responsible for the James Bond series of films, to Barbara and her half-brother Michael G. Wilson. They continue to run the company as of 2021.[48] After the death of Albert Broccoli, his daughter, Barbara Dana Broccoli[49] took over Eon Productions to continue her father’s tradition together with Michael Wilson as a partner at Eon Productions in United Kingdom. She was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II in the 2008 New Year Honours.[50] She and Wilson received the David O. Selznick Achievement Award in Theatrical Motion Pictures in 2013. In 2014, she was selected as a member of the jury for the 64th Berlin International Film Festival.[51] Barbara Broccoli became President of the National Youth Theatre[52] after the success of their 60th Anniversary Diamond Gala at Shaftesbury Theatre in 2016. Barbara married director and film producer Frederick M. Zollo[53] in 1991, and they had one child. They later divorced.[54]

Baebara Broccoli started working in the Bond franchise at the age of 17, working in the publicity department of The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). Several years later, she served as an assistant director on Octopussy (1983). Soon afterward, she progressed to become an associate producer of the film The Living Daylights (1987).[55] Her most significant role has been as a producer of the Bond films starring Pierce Brosnan and later Daniel Craig.[56]

There were seven different actors playing the role of James Bond. The first was Sean Connery, followed by Australian, George Lazenby, who featured only in one movie: “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnon and finally Daniel Craig. Most cinemagoers are unaware that David Niven also featured in an earlier version of Casino Royale in 1967 as James Bond.

It, therefore, appears that while Bond, the character of James Bond has died, his legacy will continue on the big screen. It may be Nomi as the lead, a new 007, not James Bond, surrounded by familiar faces, or, possibly be a completely new beginning by the new owners of Metro Goldwyn Meyer Studios[57], Amazon[58], is an interesting prospect for the progeny of Ian Fleming, Saltzman, Wilson and the Broccolis in the future.

The Bottom Line is that with James Bond dead, the world and even space is at the total mercy of megalomaniacs, terrorist, and dictators. In fact, the Universe has become a much more dangerous place to live and die, but there is “No Time To Die”. However, the designation, 007, as well as the “licence to kill”[59] remains, to be reallocated, as well as redesignated to a new operative of MI6. Humanoids can only pray for the soul of James Bond to rest in peace, while a worthy successor of the crown of James Bond is found by Eon Productions. This will resurrect the know all, do all and always victorious character, not as James Bond unless “No Time To Die[60]” was a 165 minute dream, which the movie makers, can do to extricate themselves from a dead end. James Bond was a special icon created by Ian Lancaster Fleming in 1952, 70 years ago, probably based on his alter ego, to enthrall book readers and brought to life by Eon Productions to entertain cinema audiences, worldwide for nearly six decades and hopefully will continue to do so in future years to come.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vice_Admiral

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miss_Moneypenny

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q_(James_Bond)#:~:text=Q%20is%20a%20fictional%20character,of%20the%20British%20Secret%20Service.

[5] https://apnews.com/article/entertainment-lashana-lynch-barbara-broccoli-movies-arts-and-entertainment-2bc23631d2e62ea1bc2cd9774add9f05

[6] https://jamesbond.fandom.com/wiki/M_(Ralph_Fiennes)

[7] https://www.gamesradar.com/no-time-to-die-james-bond-eulogy-jack-london/#:~:text=M%20(Ralph%20Fiennes)%20delivers%20a%20fitting%20eulogy%20for%20James%20Bond%20that%20goes%3A%20%22The%20proper%20function%20of%20man%20is%20to%20live%2C%20not%20to%20exist.%20I%20shall%20not%20waste%20my%20days%20in%20trying%20to%20prolong%20them.%20I%20shall%20use%20my%20time

[8] https://www.gamesradar.com/no-time-to-die-james-bond-eulogy-jack-london/#:~:text=James%20Bond%20was%20certainly%20a%20man%20who%20lived%20rather%20than%20existed%20and%20the%20passage%2C%20written%20by%20American%20novelist%20Jack%20London%2C%20was%20first%20published%20by%20the%20San%20Francisco%20Bulletin%20in%201916.%20The%20passage%20later%20served%20as%20the%20introduction%20to%20a%20compilation%20of%20London%E2%80%99s%20short%20stories%20published%20posthumously%20in%201956.

[9] https://www.gamesradar.com/no-time-to-die-james-bond-eulogy-jack-london/#:~:text=As%20pointed%20out,use%20my%20time.%22

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Zimmer

[11] https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=We+Have+all+the+time+in+the+World&view=detail&mid=9D4F482572CEFBE5FDBF9D4F482572CEFBE5FDBF&FORM=VIRE

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Armstrong

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Barry_(composer)

[14] On Her Majesty’s Secret Service liner notes, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – Ultimate Edition (©2006 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc.).

[15] John Barry. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service audio commentary. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Ultimate Edition, Disc 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_Time_To_Die_(2020_film)

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dan_Romer

[18] Burlingame, Jon (6 January 2020). “‘No Time to Die’: Hans Zimmer Takes Over as Composer on Bond Movie (EXCLUSIVE)”. Variety.

[19] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2382320/characters/nm1785339

[20] https://jamesbond.fandom.com/wiki/SPECTRE

[22] https://screenrant.com/james-bond-no-time-safin-villain/#:~:text=While%20Safin%20is%20not%20necessarily%20a%20physical%20match%20for%20007%2C%20he%20is%20nevertheless%20extremely%20intelligent%2C%20dangerous%2C%20and%20a%20worthy%20adversary.%20He%20has%20many%20elements%20to%20his%20character%20that%20both%20feeds%20into%2C%20and%20in%20some%20cases%20are%20at%20odds%20with%2C%20his%20nefarious%20plan.

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanorobotics

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ian_Fleming#:~:text=Ian%20Lancaster%20Fleming%20(28,portrayed%20by%20seven%20actors.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ian_Fleming#:~:text=Ian%20Lancaster%20Fleming%20(28,portrayed%20by%20seven%20actors.

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ian_Fleming

[27] https://james-bond-literary.fandom.com/wiki/SMERSH#:~:text=SMERSH%20(in%20capitalised,supposed%20to%20be

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_T._Kirk#:~:text=For%20other%20uses%2C%20see%20James%20Kirk%20%28disambiguation%29.%20James,serving%20aboard%20the%20starship%20USS%20Enterprise%20as%20captain.

[29] https://www.jamesbondlifestyle.com/product/brioni-suits

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Saltzman

[31] https://www.google.com/search?q=Harry+Saltzman&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Harry+Saltzman&aqs=chrome..69i57.1753083j1j9&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=Herschel%20Saltzman%20known%20as%20Harry%20Saltzman%2C%20was%20a%20Canadian%20theatre%20and%20film%20producer%2C%20He%20is%20best%20remembered%20for%20co-producing%20the%20first%20nine%20of%20the%20James%20Bond%C2%A0

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_R._Broccoli

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Saltzman#:~:text=In%20early%201961,Dana%20and%20Jacqueline.

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Saltzman#:~:text=Saltzman%20would%20remain%20Broccoli%27s%20partner%20up%20through%20the%20ninth%20film%20in%20the%20series%2C%201974%27s%20The%20Man%20with%20the%20Golden%20Gun.

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eon_Productions

[36] https://www.reddit.com/r/gaming/comments/1clp6b/i_keep_throwing_my_money_at_the_screen_but/

[37] Hendrix, Grady (June 26, 2007). “The state of the ninja”. Slate Magazine.

[38] ‘Inside You Only Live Twice: An Original Documentary,’ 2000, MGM Home Entertainment Inc.

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_R._Broccoli#:~:text=Broccoli%20married%20three%20times.

[40] https://web.archive.org/web/20180612140642/http://www.qgazette.com/news/2004-03-10/features/003.html

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_G._Wilson

[42] https://www.google.com/search?q=Michael+G.+Wilson&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=Michael+G.+Wilson&aqs=chrome..69i57.1934117j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=is%20the%20stepson%20of%20Albert%20%22Cubby%22%20Broccoli%2C%20and%20has%20worked%20as%20a%20producer%20and/or%20screenwriter%20on%20every%20James%C2%A0

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-0-7522-1162-6

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_R._Broccoli#:~:text=Michael%20Wilson%20worked%20his%20way%20up%20through%20the%20production%20company%20to%20co-write%20and%20co-produce.%20Barbara%20Broccoli%2C%20in%20her%20turn%2C%20served%20in%20several%20capacities%20under%20her%20father%27s%20tutelage%20from%20the%201980s%20on.%20Wilson%20and%20Barbara%20Broccoli%20have%20co-produced%20the%20films%20since%20Albert%20Broccoli%27s%20death.

[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_R._Broccoli#:~:text=Moonraker%20(1979)%20%E2%80%93%20Tourist%20in%20Venice%20with%20wife%20Dana%20Broccoli

[46] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_R._Broccoli#:~:text=Broccoli%20died%20at,EON%20Productions%20presents%22.

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_R._Broccoli#:~:text=In%20recognition%20of,EON%20Productions%20presents%22

[48] Barnes, Brooks (November 6, 2015). “A Family Team Looks for James Bond’s Next Assignment”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331

[49] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Broccoli

[50] https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/416561/NY_2008.csv/preview

[51]http://www.berlinale.de/en/presse/pressemitteilungen/alle/Alle-Detail_21332.html

[52] https://www.nyt.org.uk/about-us/meet-the-team

[53] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Zollo

[54] Barnes, Brooks (November 6, 2015). “A Family Team Looks for James Bond’s Next Assignment”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Broccoli#:~:text=Prigg%C3%A9%2C%20Steven%20(2004).%20Movie%20moguls%20speak%3A%20interviews%20with%20top%20film%20producers.%20McFarland%20Publishing.%20p.%C2%A017.%20ISBN%C2%A09780786419296.

[56] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Broccoli#:~:text=Masters%2C%20Tim%20(October%2024%2C%202012).%20%22Skyfall%20premiere%20is%20biggest%20and%20best%20%E2%80%93%20Daniel%20Craig%22.%20BBC.%20Barbara%20Broccoli%2C%20who%20co-produces%20the%20Bond%20films%20with%20Michael%20G.%20Wilson%2C%20said%20Skyfall%20was%20%27classic%20Bond%20but%20with%20a%20contemporary%20feel%27

[57] https://www.google.com/search?q=mgm+amazon&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwizvZi4n7zzAhXIPsAKHaqkASQQ_AUoAnoECAEQBA&biw=1242&bih=545&dpr=1.1#imgrc=hDJ0ccQxMcgEuM

[58] https://www.theverge.com/22567113/amazon-mgm-deal-chaos-reigns

[59] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Licence_to_kill_(concept)

[60] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_Time_to_Die

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Art, Entertainment, James Bond, Literature, UK

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 11 Oct 2021.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: “Eulogy” for James Bond: World Peace Is at Peril, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Sorry, but this sort of detail seems to me to be the waste of a life. The Cold War was bad enough and the UK remaining hatred of Russia is no joke.

Dear Ms Rosemerry Greetings from Durban, South Africa. Thank you for reading my “Eulogy” and submitting your comment. I am unsure if your statement “waste of life” is directed against James Bond or the author. If it is against the author, I submit my humble apologies for wasting your time explaining the detailed background of the life of James Bond, both in a literary context, as well as a cinematic icon of the 21st Century. You may recall that over the past 27 Bond movies, he was always shown as the unquestionably patriotic, sole crusader, sometimes assisted by Felix Leiter in his fight to eradicate the nefarious villains and restore “British order” as we know it, to prevail”. You will remember the Union Jack unfolding in the skiing scenes off the cliffs by Roger Moore and Timothy Dalton in Gibralta, in keeping with “Britain saves the world”. Furthermore, the organisation Bond was fighting changed from SMERSH to SPECTRE over the years and finally even SPECTRE executives were targeted and disposed by Lyutsifer Safin, the the villain, appropriately named, based on the infamous Lucifer, in the movie. I fully concur with your cold war sentiments, but we cannot ignore the Novichok poisoning of Mr Sergei and his daughter Miss Yulia Skripal, which was the termination attempt of Mr Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military officer and double agent for the British intelligence agency, on 04th March 2018 in the city of Salisbury, England. Hence, the residual hatred of Russia by United Kingdom. While the world is unsure who masterminded that act, we certainly do know that Mr Navalny, was also poisoned and is presently imprisoned for his democratic sentiments. This is the time we most need “James Bond to establish the facts of these two cases”, but alas he is no more.

However, I appreciate your feedback and certainly welcome your further insights, into Bond, which are most useful in terms of James Bond fighting for his country, Britain and Her Majesty, as well, as and more importantly, indirectly saving the entire world, in the process. Could you possibly imagine if Safin and his technology survived, what disastrous consequences could result for humanity, as a whole? James Bond now rests in peace, after having “honourably discharged his duties, in his own typical style, admirably. Thank you, once again for your time. Hoosen Vawda.