Jun 2022 – Understanding, “right-sizing,” and adequately respecting the role of value systems in conflict transformation avoids both over- and under-emphasis. It aims at a better understanding of the interplay between tangible conflict issues and religious or secular value systems.

Originally published by the Center for Security Studies (ETHZ) in the CSS Policy Perspectives, Vol. 9/9, November 2021 (https://bit.ly/3N0oy7W).

******************

The problem

The role of religious or secular value systems in conflict can be either over- or under-emphasized. Both tendencies can hinder conflict transformation. Over-emphasis can lead to a disconnect from tangible conflict issues (e.g. economic situation, human rights, legal-institutional set-up), while under-emphasis can lead to a lack of understanding of how actors give meaning to such tangible conflict issues.

Conflict analysis

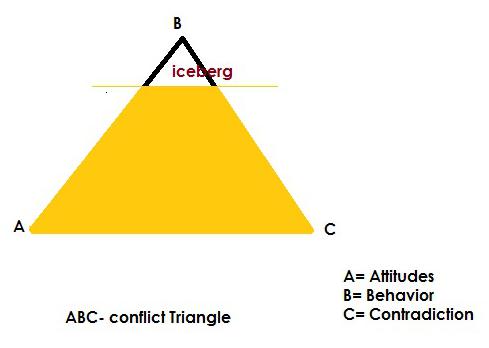

Appropriate conflict analysis is key. The Attitudes/ Behavior/Contradiction (ABC) triangle is one structured way of doing this. Even when tangible Contradictions are seen as the main “root causes” – i.e., lack of socioeconomic opportunities, poor governance, and violations of human rights – carefully considering the role of Attitudes may help address conflict Contradictions and Behavior.

Re-interpretation

A change in attitude often precedes an actor’s decision to stop using violence. This may require a (re-)interpretation or re-reading of the actor’s value systems, even if the value systems as such do not change. Such interpretation processes often entail an exploration of the many practical ways that actors can work towards their desired goals, all of which are options remaining in the actor’s value system. This work requires knowledge of the value system and context.

Third parties

Local and international peacebuilders can play complementary roles. To be effective, they need to be perceived as honest, fair, and impartial by the conflict actors.

************

There is no such thing as a “religious conflict,” “environmental conflict,” or “economic conflict” as conflict is always multifaceted, multi-causal and shaped by multiple interactions in a system. A further challenge when seeking to understand and address conflict and prevent violence is the socially constructed and subjective nature of what is seen as the driving or “root cause” of a conflict. Indeed, conflict often entails a disagreement on the causes of conflict. Conflict parties often have different views of the “root causes” between themselves and also often view “root causes” differently from third parties – the reason why many mediators try to avoid the term “root cause” altogether. This conundrum – the complexity of causal interactions, as well as subjective-objective intermingling in conflict analysis – has led to situations in which value systems – be they secular or religious – are often either under- or over-emphasized.

In a scenario of under-emphasizing the role of value systems, an actor is likely to see tangible factors such as poverty, poor governance, physical insecurity, and lack of rule of law as the “root causes” of the conflict. Accordingly, considering religious or secular value systems when addressing such conflicts may be seen as irrelevant or even counterproductive, as it leads to ignoring the real “root causes” of the conflict, namely the tangible, material, and empirically measurable factors. Some Western, secular policies seeking to prevent violence and address conflict are characterized by this tendency.

In a scenario of over-emphasizing the role of value systems, in contrast, an actor is likely to adopt an essentialist view, according to which value systems are seen to drive conflict independently of the given context and the tangible conflict issues and governance reality that different communities are facing. Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” thesis is an example, but some religious peacebuilding approaches also reflect this tendency.

In the following, we explore one possible way of approaching the role of value systems in conflict transformation and preventing violence. Our aim is to clarify the interplay between value systems and tangible conflict causes, thereby avoiding over- or under-emphasis of either factor. We also explore how value systems can be (re-)interpreted and how this may affect work on the tangible “root causes” of conflict. Such tangible “root causes” have, for example, been outlined in the UN Secretary-General 2015 “Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism.” This plan elaborated on the conditions conducive to, and the structural context of, violent extremism and pointed to several recurrent drivers, including: the lack of socioeconomic opportunities, poor governance, violations of human rights and the rule of law, and prolonged and unresolved conflicts. Working with value systems complements policies based on such analyses rather than replacing them.

The ABC Triangle

Johan Galtung’s “Attitude-Behavior-Contradiction” (ABC) triangle is one useful conflict analysis tool to deal with the role of value systems and other factors in conflict analysis. The ABC triangle is a framework to organize information that stems from listening to conflict actors. Every case is unique, but analytical categories help to focus our attention on certain aspects. The triangle indicates the interdependent relationships among three aspects of conflict: Attitudes, Behavior, and Contradiction that interact in various ways. For example, contradictions (e.g. colliding goals, tangible “root causes” or a social structure favourable to conflict) may shape a change of attitude (e.g. aggressiveness, hate, extremism) of the conflict parties, which may shape their behavior (e.g. violent behavior). If the conflict is not transformed peacefully, the interaction of contradiction-attitudes-behaviour may in turn exacerbate the original contradiction and may produce new ones (a vicious circle).

However, the existence of the contradiction (tangible “root causes”) does not necessarily or deterministically lead to an open violent conflict. The conflict may remain latent until at least one conflict party becomes conscious of the contradiction. This consciousness is conditioned by the value system within which the conflict parties evolve. The value system of an actor shapes the overarching set of beliefs that make sense of life and give it a purpose. They entail the set of principles governing life, especially regarding the relation and interaction with others. The value system, which may be religious or secular, is subject to interpretation by the individuals and groups in specific, practical situations.

For example, it is easier in an egalitarian value system for the conflict parties to be aware of the contradiction of lack of equal socioeconomic opportunities than it is in a non-egalitarian value system that legitimises and justifies a class/caste system. The more a system of governance is shaped by different value systems – for example, regarding gender roles or different understandings of the relationship between religion and state – the more different actors will perceive and respond in diverse ways to structural violence and the tangible “root causes” of conflict. Furthermore, within the same value system (religious or secular) there are various interpretations of its foundational texts that can lead either to a more authoritarian or more democratic regime.

Thus the value system (and its practical interpretation) shapes – but does not deterministically define – both the perception of a contradiction and the degree of awareness of it. It also shapes the way to express this awareness and to formulate the related grievances and the mode of reaction to the contradiction (tangible “root causes”). Therefore, for the same “root causes,” the reaction of individuals and groups may differ for different value systems or for different interpretations within the same value system. Herein lies great potential for preventing violence and transforming conflicts.

Implications for Conflict Transformation

If the final goal is to prevent violence and work towards sustainable peace, then – following Adam Curle – there are three complementary approaches, and all of them can benefit from consideration of the ABC triangle. All three approaches assume that violent groups are not automatically psychopaths or criminals, but they may be responding to grievances related to the tangible “root causes.”The behavior of such groups, therefore, aims at the removal of the tangible “root causes” as they perceive them.

1) The advocacy and education approach aims to foster awareness of power asymmetry, structural violence, and injustice even if one side is not yet willing to talk with the other side. Education of injustices does not just depend on “objective” facts. The awareness and perception of what is seen as “unjust” depends on the actors’ value systems.

2) The confrontational approach against injustice and structural violence is legitimized in almost all value systems, often with a clear emphasis on non-violent confrontation, such as peaceful mass protests. Most value systems, however, also legitimize the use of force under certain conditions (i.e. self-defense). Engaging with armed actors on the religiously legitimate use of force may help contain violence, even while these actors do not respect a state’s monopoly of the use of force.

3) The consensus building approach involving dialogue, negotiation, and mediation, aims to prevent, manage, or resolve conflict and ultimately remove the tangible “root causes” and change the context (e.g., improve the governance). Distinct from the approaches above that can be unilateral, in this approach, at least two actors need to be ready to talk with each other with the aim of exploring cooperative agreements or actions. If the aim is long-term transformation, efforts must engage diverse actors and respect inclusiveness, involving all relevant stakeholders (local, regional, and international) and also include the actors who express grievances and inhabit different value systems. If the aim is more short-term, to contain or manage violence, the approach is to prevent and reduce violence even when the contradiction and tangible “root causes” remain. This approach seeks to influence indirectly (or even directly) the extremist violent groups so that they adopt, in their endeavour to remove the “root causes,” an attitude and a behavior rooted in non-violence, with a predisposition to dialogue whenever possible. This influence is exerted without altering the reference and value system of these groups, but rather through a process of interpretation as elaborated below.

Importance of (Re-)Interpretation

Both for short-term management and long-term transformation, discussing the interplay of the reference (value system) and the contradiction (context, tangible “root causes”) can trigger a process of interpretation on how to practically use the value system to reach the desired goal. This interpretation determines the attitudes and, consequently, the behavior towards others.

How do such reinterpretations occur? A change in attitude and behavior requires an interpretation shift operated through re-reading of the value system that itself does not need to be changed. This also entails re-assessing the context, and learning from one’s own and others’ past experiences, achievements, and disillusions. This could work for any kind of active group based on any kind of value system as reference, be it religious or secular.

Let us explore an example in the Jewish Tradition. Sometimes the distinction between the “final times” and the “before final times” helps, as there may be more flexible readings of what is seen as legitimate in the before final times, as compared to what is seen as legitimate in the envisioned final times. For example, followers of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1865–1935) see it as their religious duty to actively work (i.e. before final times) towards creating the conditions that would enable full redemption (i.e. final times), for example by controlling and settling the entire land or achieving broad awareness among Jews of the inseparability of Jewish nationhood and religion. Yet as it is before the final times, plausible re-interpretations could claim that there are alternatives to full exclusive political sovereignty over the land as a way to moving towards the final times and that still satisfy core values and progress towards the final times. These might include examples from a non-territorial realm like education, thereby creating more space for other actors holding different values.

In the following we explore one reinterpretation approach found in the Muslim world. Take as an example conflicts that may arise over the relationship between religion and state or relating to democracy in the Muslim world. In the Qur’an (42:38), the principle of consultation among the members of the community regarding public affairs (Shura) is stated clearly. But the way this principle is implemented in a particular context is a matter of interpretation. Obviously, the mechanisms of consultation in the 21st century are different from those applied in the early times of Islam and have much in common with the democratic process.

In the Islamic tradition the interpretation process is called ijtihad, which refers to interpreting Islamic foundational texts and inferring jurisprudential rules in a specific context. Imam Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292–1350) defines the origin, the way, and the goal. Obviously, starting from the same origin (reference) there are various ways (possibilities of interpretation) to achieve the same desired goal. The way, subject to interpretation, must serve the goal and comply with the reference. If the way is armed action, it must comply with the religious law of war (comparable to International Humanitarian Law). The compliance to the reference norm is called wassatiya, the opposite of ghuluw (extremism).

Faith-based actors engaged in social and political change may be strict in being faithful to the reference and the discourse that goes with it (radicality or orthodoxy) but flexible in the way to achieve the goal if they are offered various options. Radicality is not extremism.

Interpretation/ijtihad is not open to everybody. It requires legitimacy and expertise. It is the function and duty of recognized and credible Islamic scholars (guardians of the religious orthodoxy). The (re-)interpretation can be the fruit of genuine internal deliberations among scholars within or close to activist groups. It can also be assisted by a third party that must be knowledgeable of the reference and the context and perceived as honest, fair, and impartial by the actors. However, the mediated (re-)interpretation can be achieved only when mediators fulfill the following conditions: 1) Respecting that the actors are faithful to their reference. 2) Accepting their legitimate goals. 3) Listening to their description of the context (narrative) and acknowledging their grievances. 4) Generating options with them and showing a range of possibilities.

A successful (re-)interpretation process will lead to a change of attitude and behavior at the individual and group level since the member of the group and the group as a whole operate within a religious-legal framework shaped by the credible religious jurists (fuqaha) and scholars (ulama). Any action on this framework will ultimately have an impact on individual and group behavior and any effort to make sense of and address tangible “root causes.”

Further Reading

Jean-Nicolas Bitter and Owen Frazer, “The Instrumentalization of Religion in Conflict”, CSS Policy Perspectives 8/5 (2020). This article cautions against using the “instrumentalization of religion” argument too quickly.

Abbas Aroua, “Transforming Religious-Political Conflicts: Decoding-Recoding Positions and Goals”, Politorbis 52, (2011). This article clarifies the interplay between religious and political factors in conflict transformation.

Alistair Davison, “Engaging Credible Religious Leaders in the Prevention of Extremism and Extreme Violence – our Methodology”, Cordoba Peace Institute, June 2018. This article clarifies the need to work with credible scholars for interpretation/ijtihad.

Simon J. A. Mason, “Local Mediation with Religious Actors in Israel-Palestine”, CSS Analyses in Security Policy 281, (2021). This article explores how local mediators operate in Israel-Palestine.

_______________________________________________

Abbas Aroua is a medical physicist and adjunct professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the Lausanne University, Switzerland. He is director of the Cordoba Peace Institute Geneva and Convener for the Arab world of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Abbas Aroua is a medical physicist and adjunct professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the Lausanne University, Switzerland. He is director of the Cordoba Peace Institute Geneva and Convener for the Arab world of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Jean-Nicolas Bitter is Senior Advisor on Religion, Politics and Conflict at the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The opinions expressed here reflect his personal views and are not those of the Swiss FDFA.

Simon J A Mason, Center for Security Studies (CSS) ETH Zürich, working in the Culture and Religion in Mediation program (CARIM, a CSS ETH Zürich and Swiss FDFA initiative).