Leo Tolstoy (9 Sep 1828 – 20 Nov 1910)

BIOGRAPHIES, 5 Sep 2022

Gary Saul Morson | Encyclopædia Britannica - TRANSCEND Media Service

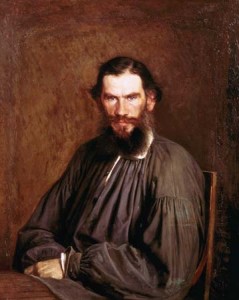

Leo Tolstoy, also spelled Tolstoi, Russian in full Lev Nikolayevich, Graf (count) Tolstoy (born Aug 28 [Sep 9, New Style], 1828, Yasnaya Polyana, Tula province, Russian Empire—died Nov 7 [Nov 20], 1910, Astapovo, Ryazan province), Russian author, a master of realistic fiction and one of the world’s greatest novelists.

Tolstoy is best known for his two longest works, War and Peace (1865–69) and Anna Karenina (1875–77), which are commonly regarded as among the finest novels ever written. War and Peace in particular seems virtually to define this form for many readers and critics. Among Tolstoy’s shorter works, The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) is usually classed among the best examples of the novella. Especially during his last three decades Tolstoy also achieved world renown as a moral and religious teacher. His doctrine of nonresistance to evil had an important influence on Gandhi. Although Tolstoy’s religious ideas no longer command the respect they once did, interest in his life and personality has, if anything, increased over the years.

Most readers will agree with the assessment of the 19th-century British poet and critic Matthew Arnold that a novel by Tolstoy is not a work of art but a piece of life; the Russian author Isaak Babel commented that, if the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy. Critics of diverse schools have agreed that somehow Tolstoy’s works seem to elude all artifice. Most have stressed his ability to observe the smallest changes of consciousness and to record the slightest movements of the body. What another novelist would describe as a single act of consciousness, Tolstoy convincingly breaks down into a series of infinitesimally small steps. According to the English writer Virginia Woolf, who took for granted that Tolstoy was “the greatest of all novelists,” these observational powers elicited a kind of fear in readers, who “wish to escape from the gaze which Tolstoy fixes on us.” Those who visited Tolstoy as an old man also reported feelings of great discomfort when he appeared to understand their unspoken thoughts. It was commonplace to describe him as godlike in his powers and titanic in his struggles to escape the limitations of the human condition. Some viewed Tolstoy as the embodiment of nature and pure vitality, others saw him as the incarnation of the world’s conscience, but for almost all who knew him or read his works, he was not just one of the greatest writers who ever lived but a living symbol of the search for life’s meaning.

Early Years

The scion of prominent aristocrats, Tolstoy was born at the family estate, about 130 miles (210 kilometres) south of Moscow, where he was to live the better part of his life and write his most-important works. His mother, Mariya Nikolayevna, née Princess Volkonskaya, died before he was two years old, and his father Nikolay Ilich, Graf (count) Tolstoy, followed her in 1837. His grandmother died 11 months later, and then his next guardian, his aunt Aleksandra, in 1841. Tolstoy and his four siblings were then transferred to the care of another aunt in Kazan, in western Russia. Tolstoy remembered a cousin who lived at Yasnaya Polyana, Tatyana Aleksandrovna Yergolskaya (“Aunt Toinette,” as he called her), as the greatest influence on his childhood, and later, as a young man, Tolstoy wrote some of his most-touching letters to her. Despite the constant presence of death, Tolstoy remembered his childhood in idyllic terms. His first published work, Detstvo (1852; Childhood), was a fictionalized and nostalgic account of his early years.

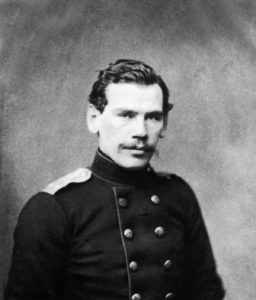

Educated at home by tutors, Tolstoy enrolled in the University of Kazan in 1844 as a student of Oriental languages. His poor record soon forced him to transfer to the less-demanding law faculty, where he wrote a comparison of the French political philosopher Montesquieu’s The Spirit of Laws and Catherine the Great’s nakaz (instructions for a law code). Interested in literature and ethics, he was drawn to the works of the English novelists Laurence Sterne and Charles Dickens and, especially, to the writings of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau; in place of a cross, he wore a medallion with a portrait of Rousseau. But he spent most of his time trying to be comme il faut (socially correct), drinking, gambling, and engaging in debauchery. After leaving the university in 1847 without a degree, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana, where he planned to educate himself, to manage his estate, and to improve the lot of his serfs. Despite frequent resolutions to change his ways, he continued his loose life during stays in Tula, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. In 1851 he joined his older brother Nikolay, an army officer, in the Caucasus and then entered the army himself. He took part in campaigns against the native peoples and, soon after, in the Crimean War (1853–56).

In 1847 Tolstoy began keeping a diary, which became his laboratory for experiments in self-analysis and, later, for his fiction. With some interruptions, Tolstoy kept his diaries throughout his life, and he is therefore one of the most copiously documented writers who ever lived. Reflecting the life he was leading, his first diary begins by confiding that he may have contracted a venereal disease. The early diaries record a fascination with rule-making, as Tolstoy composed rules for diverse aspects of social and moral behaviour. They also record the writer’s repeated failure to honour these rules, his attempts to formulate new ones designed to ensure obedience to old ones, and his frequent acts of self-castigation. Tolstoy’s later belief that life is too complex and disordered ever to conform to rules or philosophical systems perhaps derives from these futile attempts at self-regulation.

First Publications

Concealing his identity, Tolstoy submitted Childhood for publication in Sovremennik (“The Contemporary”), a prominent journal edited by the poet Nikolay Nekrasov. Nekrasov was enthusiastic, and the pseudonymously published work was widely praised. During the next few years Tolstoy published a number of stories based on his experiences in the Caucasus, including “Nabeg” (1853; “The Raid”) and his three sketches about the Siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War: “Sevastopol v dekabre mesyatse” (“Sevastopol in December”), “Sevastopol v maye” (“Sevastopol in May”), and “Sevastopol v avguste 1855 goda” (“Sevastopol in August”; all published 1855–56). The first sketch, which deals with the courage of simple soldiers, was praised by the tsar. Written in the second person as if it were a tour guide, this story also demonstrates Tolstoy’s keen interest in formal experimentation and his lifelong concern with the morality of observing other people’s suffering. The second sketch includes a lengthy passage of a soldier’s stream of consciousness (one of the early uses of this device) in the instant before he is killed by a bomb. In the story’s famous ending, the author, after commenting that none of his characters are truly heroic, asserts that

the hero of my story—whom I love with all the power of my soul…who was, is, and ever will be beautiful—is the truth.

Readers ever since have remarked on Tolstoy’s ability to make such “absolute language,” which usually ruins realistic fiction, aesthetically effective.

After the Crimean War Tolstoy resigned from the army and was at first hailed by the literary world of St. Petersburg. But his prickly vanity, his refusal to join any intellectual camp, and his insistence on his complete independence soon earned him the dislike of the radical intelligentsia. He was to remain throughout his life an “archaist,” opposed to prevailing intellectual trends. In 1857 Tolstoy traveled to Paris and returned after having gambled away his money.

After his return to Russia, he decided that his real vocation was pedagogy, and so he organized a school for peasant children on his estate. After touring western Europe to study pedagogical theory and practice, he published 12 issues of a journal, Yasnaya Polyana (1862–63), which included his provocative articles “Progress i opredeleniye obrazovaniya” (“Progress and the Definition of Education”), which denies that history has any underlying laws, and “Komu u kogu uchitsya pisat, krestyanskim rebyatam u nas ili nam u krestyanskikh rebyat?” (“Who Should Learn Writing of Whom: Peasant Children of Us, or We of Peasant Children?”), which reverses the usual answer to the question. Tolstoy married Sofya (Sonya) Andreyevna Bers, the daughter of a prominent Moscow physician, in 1862 and soon transferred all his energies to his marriage and the composition of War and Peace. Tolstoy and his wife had 13 children, of whom 10 survived infancy.

Tolstoy’s works during the late 1850s and early 1860s experimented with new forms for expressing his moral and philosophical concerns. To Childhood he soon added Otrochestvo (1854; Boyhood) and Yunost (1857; Youth). A number of stories centre on a single semiautobiographical character, Dmitry Nekhlyudov, who later reappeared as the hero of Tolstoy’s novel Resurrection. In “Lyutsern” (1857; “Lucerne”), Tolstoy uses the diary form first to relate an incident, then to reflect on its timeless meaning, and finally to reflect on the process of his own reflections. “Tri smerti” (1859; “Three Deaths”) describes the deaths of a noblewoman who cannot face the fact that she is dying, of a peasant who accepts death simply, and, at last, of a tree, whose utterly natural end contrasts with human artifice. Only the author’s transcendent consciousness unites these three events.

“Kholstomer” (written 1863; revised and published 1886; “Kholstomer: The Story of a Horse”) has become famous for its dramatic use of a favourite Tolstoyan device, “defamiliarization”—that is, the description of familiar social practices from the “naive” perspective of an observer who does not take them for granted. Readers were shocked to discover that the protagonist and principal narrator of “Kholstomer” was an old horse. Like so many of Tolstoy’s early works, this story satirizes the artifice and conventionality of human society, a theme that also dominates Tolstoy’s novel Kazaki (1863; The Cossacks). The hero of this work, the dissolute and self-centred aristocrat Dmitry Olenin, enlists as a cadet to serve in the Caucasus. Living among the Cossacks, he comes to appreciate a life more in touch with natural and biological rhythms. In the novel’s central scene, Olenin, hunting in the woods, senses that every living creature, even a mosquito, “is just such a separate Dmitry Olenin as I am myself.” Recognizing the futility of his past life, he resolves to live entirely for others.

The Period of the Great Novels (1863–77)

Happily married and ensconced with his wife and family at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy reached the height of his creative powers. He devoted the remaining years of the 1860s to writing War and Peace. Then, after an interlude during which he considered writing a novel about Peter the Great and briefly returned to pedagogy (bringing out reading primers that were widely used), Tolstoy wrote his other great novel, Anna Karenina. These two works share a vision of human experience rooted in an appreciation of everyday life and prosaic virtues.

Voyna i mir (1865–69; War and Peace) contains three kinds of material—a historical account of the Napoleonic wars, the biographies of fictional characters, and a set of essays about the philosophy of history. Critics from the 1860s to the present have wondered how these three parts cohere, and many have faulted Tolstoy for including the lengthy essays, but readers continue to respond to them with undiminished enthusiasm.

The work’s historical portions narrate the campaign of 1805 leading to Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, a period of peace, and Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Contrary to generally accepted views, Tolstoy portrays Napoleon as an ineffective, egomaniacal buffoon, Tsar Alexander I as a phrasemaker obsessed with how historians will describe him, and the Russian general Mikhail Kutuzov (previously disparaged) as a patient old man who understands the limitations of human will and planning. Particularly noteworthy are the novel’s battle scenes, which show combat as sheer chaos. Generals may imagine they can “anticipate all contingencies,” but battle is really the result of “a hundred million diverse chances” decided on the moment by unforeseeable circumstances. In war as in life, no system or model can come close to accounting for the infinite complexity of human behaviour.

Among the book’s fictional characters, the reader’s attention is first focused on Prince Andrey Bolkonsky, a proud man who has come to despise everything fake, shallow, or merely conventional. Recognizing the artifice of high society, he joins the army to achieve glory, which he regards as truly meaningful. Badly wounded at Austerlitz, he comes to see glory and Napoleon as no less petty than the salons of St. Petersburg. As the novel progresses, Prince Andrey repeatedly discovers the emptiness of the activities to which he has devoted himself. Tolstoy’s description of his death in 1812 is usually regarded as one of the most-effective scenes in Russian literature.

The novel’s other hero, the bumbling and sincere Pierre Bezukhov, oscillates between belief in some philosophical system promising to resolve all questions and a relativism so total as to leave him in apathetic despair. He at last discovers the Tolstoyan truth that wisdom is to be found not in systems but in the ordinary processes of daily life, especially in his marriage to the novel’s most-memorable heroine, Natasha. When the book stops—it does not really end but just breaks off—Pierre seems to be forgetting this lesson in his enthusiasm for a new utopian plan.

In accord with Tolstoy’s idea that prosaic, everyday activities make a life good or bad, the book’s truly wise characters are not its intellectuals but a simple, decent soldier, Natasha’s brother Nikolay, and a generous pious woman, Andrey’s sister Marya. Their marriage symbolizes the novel’s central prosaic values.

The essays in War and Peace, which begin in the second half of the book, satirize all attempts to formulate general laws of history and reject the ill-considered assumptions supporting all historical narratives. In Tolstoy’s view, history, like battle, is essentially the product of contingency, has no direction, and fits no pattern. The causes of historical events are infinitely varied and forever unknowable, and so historical writing, which claims to explain the past, necessarily falsifies it. The shape of historical narratives reflects not the actual course of events but the essentially literary criteria established by earlier historical narratives.

According to Tolstoy’s essays, historians also make a number of other closely connected errors. They presume that history is shaped by the plans and ideas of great men—whether generals or political leaders or intellectuals like themselves—and that its direction is determined at dramatic moments leading to major decisions. In fact, however, history is made by the sum total of an infinite number of small decisions taken by ordinary people, whose actions are too unremarkable to be documented. As Tolstoy explains, to presume that grand events make history is like concluding from a view of a distant region where only treetops are visible that the region contains nothing but trees. Therefore Tolstoy’s novel gives its readers countless examples of small incidents that each exert a tiny influence—which is one reason that War and Peace is so long. Tolstoy’s belief in the efficacy of the ordinary and the futility of system-building set him in opposition to the thinkers of his day. It remains one of the most-controversial aspects of his philosophy.

In Anna Karenina (1875–77) Tolstoy applied these ideas to family life. The novel’s first sentence, which indicates its concern with the domestic, is perhaps Tolstoy’s most famous: “All happy families resemble each other; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Anna Karenina interweaves the stories of three families, the Oblonskys, the Karenins, and the Levins.

The novel begins at the Oblonskys, where the long-suffering wife Dolly has discovered the infidelity of her genial and sybaritic husband Stiva. In her kindness, care for her family, and concern for everyday life, Dolly stands as the novel’s moral compass. By contrast, Stiva, though never wishing ill, wastes resources, neglects his family, and regards pleasure as the purpose of life. The figure of Stiva is perhaps designed to suggest that evil, no less than good, ultimately derives from the small moral choices human beings make moment by moment.

Stiva’s sister Anna begins the novel as the faithful wife of the stiff, unromantic, but otherwise decent government minister Aleksey Karenin and the mother of a young boy, Seryozha. But Anna, who imagines herself the heroine of a romantic novel, allows herself to fall in love with an officer, Aleksey Vronsky. Schooling herself to see only the worst in her husband, she eventually leaves him and her son to live with Vronsky. Throughout the novel, Tolstoy indicates that the romantic idea of love, which most people identify with love itself, is entirely incompatible with the superior kind of love, the intimate love of good families. As the novel progresses, Anna, who suffers pangs of conscience for abandoning her husband and child, develops a habit of lying to herself until she reaches a state of near madness and total separation from reality. She at last commits suicide by throwing herself under a train. The realization that she may have been thinking about life incorrectly comes to her only when she is lying on the track, and it is too late to save herself.

The third story concerns Dolly’s sister Kitty, who first imagines she loves Vronsky but then recognizes that real love is the intimate feeling she has for her family’s old friend, Konstantin Levin. Their story focuses on courtship, marriage, and the ordinary incidents of family life, which, in spite of many difficulties, shape real happiness and a meaningful existence. Throughout the novel, Levin is tormented by philosophical questions about the meaning of life in the face of death. Although these questions are never answered, they vanish when Levin begins to live correctly by devoting himself to his family and to daily work. Like his creator Tolstoy, Levin regards the systems of intellectuals as spurious and as incapable of embracing life’s complexity.

Both War and Peace and Anna Karenina advance the idea that ethics can never be a matter of timeless rules applied to particular situations. Rather, ethics depends on a sensitivity, developed over a lifetime, to particular people and specific situations. Tolstoy’s preference for particularities over abstractions is often described as the hallmark of his thought.

Conversion and Religious Beliefs

Upon completing Anna Karenina, Tolstoy fell into a profound state of existential despair, which he describes in his Ispoved (1884; My Confession). All activity seemed utterly pointless in the face of death, and Tolstoy, impressed by the faith of the common people, turned to religion. Drawn at first to the Russian Orthodox church into which he had been born, he rapidly decided that it, and all other Christian churches, were corrupt institutions that had thoroughly falsified true Christianity. Having discovered what he believed to be Christ’s message and having overcome his paralyzing fear of death, Tolstoy devoted the rest of his life to developing and propagating his new faith. He was excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox church in 1901.

In the early 1880s he wrote three closely related works, Issledovaniye dogmaticheskogo bogosloviya (written 1880; An Examination of Dogmatic Theology), Soyedineniye i perevod chetyrokh yevangeliy (written 1881; Union and Translation of the Four Gospels), and V chyom moya vera? (written 1884; What I Believe); he later added Tsarstvo bozhiye vnutri vas (1893; The Kingdom of God Is Within You) and many other essays and tracts. In brief, Tolstoy rejected all the sacraments, all miracles, the Holy Trinity, the immortality of the soul, and many other tenets of traditional religion, all of which he regarded as obfuscations of the true Christian message contained, especially, in the Sermon on the Mount. He rejected the Old Testament and much of the New, which is why, having studied Greek, he composed his own “corrected” version of the Gospels. For Tolstoy, “the man Jesus,” as he called him, was not the son of God but only a wise man who had arrived at a true account of life. Tolstoy’s rejection of religious ritual contrasts markedly with his attitude in Anna Karenina, where religion is viewed as a matter not of dogma but of traditional forms of daily life.

Stated positively, the Christianity of Tolstoy’s last decades stressed five tenets: be not angry, do not lust, do not take oaths, do not resist evil, and love your enemies. Nonresistance to evil, the doctrine that inspired Gandhi, meant not that evil must be accepted but only that it cannot be fought with evil means, especially violence. Thus, Tolstoy became a pacifist. Because governments rely on the threat of violence to enforce their laws, Tolstoy also became a kind of anarchist. He enjoined his followers not only to refuse military service but also to abstain from voting or from having recourse to the courts. He therefore had to go through considerable inner conflict when it came time to make his will or to use royalties secured by copyright even for good works. In general, it may be said that Tolstoy was well aware that he did not succeed in living according to his teachings.

Tolstoy based the prescription against oaths (including promises) on an idea adapted from his early work: the impossibility of knowing the future and therefore the danger of binding oneself in advance. The commandment against lust eventually led him to propose (in his afterword to Kreytserova sonata [1891; The Kreutzer Sonata], a dark novella about a man who murders his wife) total abstinence as an ideal. His wife, already concerned about their strained relations, objected. In defending his most-extreme ideas, Tolstoy compared Christianity to a lamp that is not stationary but is carried along by human beings; it lights up ever new moral realms and reveals ever higher ideals as mankind progresses spiritually.

Fiction After 1880

Tolstoy’s fiction after Anna Karenina may be divided into two groups. He wrote a number of moral tales for common people, including “Gde lyubov, tam i bog” (written 1885; “Where Love Is, God Is”), “Chem lyudi zhivy” (written 1882; “What People Live By”), and “Mnogo li cheloveku zemli nuzhno” (written 1885; “How Much Land Does a Man Need”), a story that the Irish novelist James Joyce rather extravagantly praised as “the greatest story that the literature of the world knows.” For educated people, Tolstoy wrote fiction that was both realistic and highly didactic. Some of these works succeed brilliantly, especially Smert Ivana Ilicha (written 1886; The Death of Ivan Ilyich), a novella describing a man’s gradual realization that he is dying and that his life has been wasted on trivialities.

Otets Sergy (written 1898; Father Sergius), which may be taken as Tolstoy’s self-critique, tells the story of a proud man who wants to become a saint but discovers that sainthood cannot be consciously sought. Regarded as a great holy man, Sergius comes to realize that his reputation is groundless; warned by a dream, he escapes incognito to seek out a simple and decent woman whom he had known as a child. At last he learns that not he but she is the saint, that sainthood cannot be achieved by imitating a model, and that true saints are ordinary people unaware of their own prosaic goodness. This story therefore seems to criticize the ideas Tolstoy espoused after his conversion from the perspective of his earlier great novels.

In 1899 Tolstoy published his third long novel, Voskreseniye (Resurrection); he used the royalties to pay for the transportation of a persecuted religious sect, the Dukhobors, to Canada. The novel’s hero, the idle aristocrat Dmitry Nekhlyudov, finds himself on a jury where he recognizes the defendant, the prostitute Katyusha Maslova, as a woman whom he once had seduced, thus precipitating her life of crime. After she is condemned to imprisonment in Siberia, he decides to follow her and, if she will agree, to marry her. In the novel’s most-remarkable exchange, she reproaches him for his hypocrisy: once you got your pleasure from me, and now you want to get your salvation from me, she tells him. She refuses to marry him, but, as the novel ends, Nekhlyudov achieves spiritual awakening when he at last understands Tolstoyan truths, especially the futility of judging others. The novel’s most-celebrated sections satirize the church and the justice system, but the work is generally regarded as markedly inferior to War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

Tolstoy’s conversion led him to write a treatise and several essays on art. Sometimes he expressed in more-extreme form ideas he had always held (such as his dislike for imitation of fashionable schools), but at other times he endorsed ideas that were incompatible with his own earlier novels, which he rejected. In Chto takoye iskusstvo? (1898; What Is Art?) he argued that true art requires a sensitive appreciation of a particular experience, a highly specific feeling that is communicated to the reader not by propositions but by “infection.” In Tolstoy’s view, most celebrated works of high art derive from no real experience but rather from clever imitation of existing art. They are therefore “counterfeit” works that are not really art at all.

Tolstoy further divides true art into good and bad, depending on the moral sensibility with which a given work infects its audience. Condemning most acknowledged masterpieces, including William Shakespeare’s plays as well as his own great novels, as either counterfeit or bad, Tolstoy singled out for praise the biblical story of Joseph and, among Russian works, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The House of the Dead (1861–62) and some stories by his young friend Anton Chekhov. He was cool to Chekhov’s drama, however, and, in a celebrated witticism, once told Chekhov that his plays were even worse than Shakespeare’s.

Tolstoy’s late works also include a satiric drama, Zhivoy trup (written 1900; The Living Corpse), and a harrowing play about peasant life, Vlast tmy (written 1886; The Power of Darkness). After his death, a number of unpublished works came to light, most notably the novella Khadji-Murat (1904; Hadji-Murad), a brilliant narrative about the Caucasus reminiscent of Tolstoy’s earliest fiction.

Last Years

With the notable exception of his daughter Aleksandra, whom he made his heir, Tolstoy’s family remained aloof from or hostile to his teachings. His wife especially resented the constant presence of disciples, led by the dogmatic V.G. Chertkov, at Yasnaya Polyana. Their once happy life had turned into one of the most famous bad marriages in literary history. The story of his dogmatism and her penchant for scenes has excited numerous biographers to take one side or the other. Because both kept diaries, and indeed exchanged and commented on each other’s diaries, their quarrels are almost too well documented.

Tormented by his domestic situation and by the contradiction between his life and his principles, in 1910 Tolstoy at last escaped incognito from Yasnaya Polyana, accompanied by Aleksandra and his doctor. In spite of his stealth and desire for privacy, the international press was soon able to report on his movements. Within a few days, he contracted pneumonia and died of heart failure at the railroad station of Astapovo.

Assessment

In contrast to other psychological writers, such as Dostoyevsky, who specialized in unconscious processes, Tolstoy described conscious mental life with unparalleled mastery. His name has become synonymous with an appreciation of contingency and of the value of everyday activity. Oscillating between skepticism and dogmatism, Tolstoy explored the most-diverse approaches to human experience. Above all, his greatest works, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, endure as the summit of realist fiction.

__________________________________

Gary Saul Morson: Frances Hooper Professor of the Arts and Humanities; Professor of Slavic Languages, Northwestern University, Illinois. Author of Anna Karenina in Our Time, Hidden in Plain View: Narrative and Creative Potentials in “War and Peace,” and others.

Go to Original – britannica.com

Tags: Biography, Gandhi, Leo Tolstoy, Literature, Russia, USSR

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.