“Monsters Breed Monsters”: The Impact of Systemic Peace Disruption on Children in Violent Conflict Situations

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 19 Sep 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

This publication contains graphic images which may be disturbing to certain readers. Parental guidance is advised.

******************************

The Western countries are guilty of allowing warring parties globally to breed children and transform them into terrorists of the future who will come back to haunt them and seek revenge.[i]

17 Sep 2022 – This publication, on children in war zones, documents the long-term effects on minors , as they grow up under the most physically and psychologically traumatic conditions in their formative years of their lives. This will ultimately result in the unleashing of these “valueless, traditionless, cultureless and stateless individuals” who will definite payback to the countries which have resulted in their status quo, even if they have been relocated to safe havens in the western states, “The Revenge Is Theirs”.

The presence and participation of children in wars can be traced back to Middle Ages and Napoleonic Wars. Children fought in the American Civil war, significantly contributed to the Battle of New Market which was fought in Virginia on 15th May 1864.[3] Children were also fighting in the World War II, especially noted to serve as “Hitler Youth”.[4] However, presently, the numbers of child victims are increasing in proportion to the civilian casualties in war zones. In 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, about half the war victims were civilians while it was almost 90 percent by the end of the 1980s.[5] Children comprise a large part of the population affected by wars, data from the American Psychological Association shows, of the 95 percent of civilians killed in recent years by modern armed conflicts, approximately 50 percent of them were children.[6] According to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the estimated casualties of children during the last decade was: “2 million killed, 4–5 million disabled, 12 million left homeless, more than 1 million orphaned or separated from their parents, and some 10 million psychologically traumatized”.[7] Currently, there are over two million child refugees fleeing from Syria and over 870,000 refugees from Somalia.[8] Among 100,000 people who have been killed in Syria, at least 10,000 were children.[9]

Direct exposure to violence on children will result in death and injury. such as bombing and combats, children are killed during conflicts. In 2017 alone, there were 1,210 terrorist attacks around the world, mostly happening in Middle East region and 8,074 fatalities.[10] There were nine terrorist incidents with more than hundred deaths in conflict zones. Under the Trump administration, civilian casualties from the United States armed forces are at all-time high in Syria and Iraq.[11] Also, children are more likely to be injured by landmines. Twenty percent of landmine victims are children in mine-affected countries.[12] They are often intrigued by colorful appearance of landmines and explosives. Children can lose sight or hearing; lose body parts and suffer from the trauma.[13] At least 8,605 people were killed or injured by landmines in 2016 and 6,967 casualties in 2015.[14] Most of them were civilians and 42 percent of civilian casualties were children and the number of child casualties were at least 1,544 in 2016.[15]

Another serious challenge is sexual violence against minors. The United Nations define the term “conflict-related sexual violence” as “rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilisation, forced marriage, and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict”.[16] More than 20,000 Muslim girls and women have been raped in Bosnia since 1992. Many cases in Rwanda show that every surviving adolescent girl was raped.[17] Sexual violence also causes sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS to spread.[18] One of the factors is involvement with military forces as they sexually abuse and exploit girls and women during conflicts.[19] Besides, as HIV-positive mothers give birth to HIV-infected children without anti-retroviral drugs, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS tend to spread fast.[20]

Furthermore, unmet basic needs during warfare also play an important role in this sad odyssey. War disrupts the supply of necessities to children and their families like food, water, shelter, health services, and education.[21] Lack of access to these basic needs may deprive children of their physical, social-emotional, and psychological development. In case of South Sudan, constant violent conflicts along with climate shocks greatly damaged the agriculture-based economy.[22] As a result, more than 1.1 million children are suffering from severe food shortages.[23] In countries across Africa and the Middle East, over 2.5 million children are suffering from severe acute malnutrition.[24] Economic sanctions such as trade restrictions from international community and organizations may play a role in serious economic hardship and deterioration of infrastructure in armed conflict zones.[25] This makes it extremely difficult for children to survive as they are usually in the most bottom level of socioeconomic status. As of 2001, around half a million Iraqi children were predicted to be dead due to sanctions regime.[26]

Detrimental parenting behavior can also affect child development. In a war context, families and communities are not able to provide an environment conducive to the children’s development.[27] Mike Wessells, Ph.D., a Randolph-Macon College psychology professor with extensive experience in war zones explained; “When parents are emotionally affected by war, that alters their ability to care for their children properly. War stresses increase family violence, creating a pattern that then gets passed on when the children become parents.”[28] Scarcity of resources increases cognitive load which affects attention span, cognitive capacity, and executive control that are critical abilities to reason and solve problems.[29] Reduced mental and emotional capabilities caused by stress from a war can degrade their parenting capabilities and negatively change behaviors towards children.[30]

Disruption of education also occurs with the destruction of schools during wars.[31] The human and financial resources are compromised during crisis. The United Nations reported that more than 13 million children are deprived of education opportunities and more than 8,850 schools were destroyed because of armed conflicts in the Middle East.[32] According to UNICEF report, In Yemen, 1.8 million children were out of education in 2015.[33] Between 2014 and 2015, almost half a million children in Gaza Strip were not able to go to school because of the damages on schools.[34] In Sudan, more than three million children cannot go to school because of the conflicts. In Mozambique, around 45 percent of primary schools were destroyed during the conflict.[35] Fear and disruption make it hard for children and teacher to focus on education.[36] This generates an educational gap, depriving children of essential education, building social-emotional skills, and thus reintegrating into society. In addition, gender equality can also be compromised as education disruption in armed conflict zones generally excludes girls.[37]

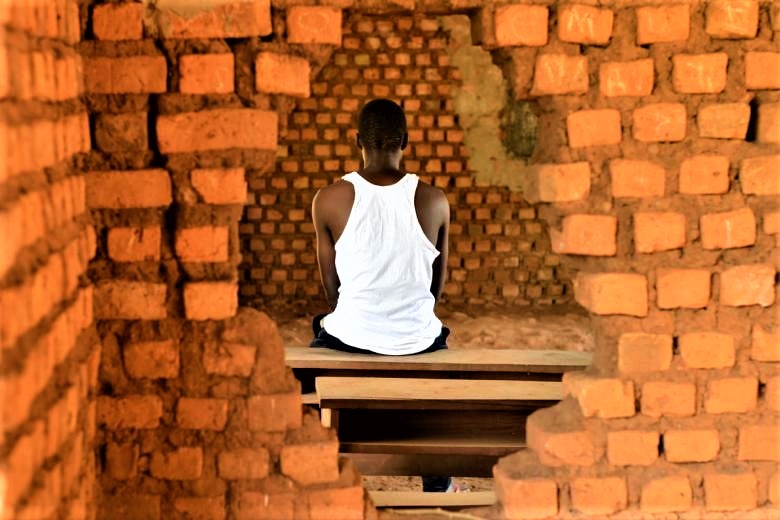

Seventeen-year-old Yuda is one of 700 children in South Sudan, who is part of a World Vision run reunification and reintegration programme for children formerly associated with armed groups.

Reportedly, there are approximately 250 million children in armed conflict zones around the world.[38] They confront personal physical and mental challenges from their war experiences.

“Armed conflict” is defined as follows, according to International Humanitarian Law:

- International armed conflicts, opposing two or more States, such as the present war in Ukraine, Ethopia and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict over the occupied land, killings oppressions and genocide of the Palestinians, in each and every aspects of their lives.

- Non-international armed conflicts, between governmental forces and nongovernmental armed groups, or between such groups only.[39] These are internal conflicts, civil wars, xenophobia, Islamophobia, disharmony between the “Haves and Have Nots”, as well as acrimony between the illiterate and the literati.

Children in war-zones may act as perpetrators, becoming child soldiers. It is estimated that there are around 300,000 child soldiers around the world and 40 percent of them are girls.[40], [41]. Children are also victims of armed conflicts. They are forced to evacuate,[42] suffer from sexually transmitted diseases and are deprived of educational opportunities.[43] As of 17th February, 2022, according to Mark Calder, who is World Vision United Kingdom’s Senior Conflict and Humanitarian Policy Advisor,[44] reports that “No child should have to experience the horrors of war, but so many do.” As of 2018, 357 million children (nearly one in six children in the world) were living in conflict-affected contexts. The effects upon children of living with violent conflict are numerous, devastating, and not always obvious. He has enumerated the following effects the ongoing conflicts have on developing children.

- Long-Term Education

Ongoing conflicts not only impact children’s access to education, but it also hampers their learning from the earliest stages of life. Children in many parts of Syria, at war for nearly 11 years now, are sometimes described as a ‘lost generation’ when it comes to schooling. But research from Peru[45] shows that, when a pregnant woman is subjected to physical violence, or mental anguish, can have an impact upon the unborn child’s physical and cognitive development. There is evidence that this affects the individual’s educational progress more significantly, even than being exposed to direct violence, in later years. There is empirical evidence of the persistent effect of exposure to political violence on human capital accumulation. The variation in conflict location and birth cohorts identifies the long and short-term effects of the civil war on educational attainment. Conditional on being exposed to violence, the average person accumulates 0.31 less years of education as an adult. In the short-term, the effects are stronger than in the long-run; these results hold when comparing children within the same household. Further, exposure to violence during early childhood leads to permanent losses. The research also explores the potential causal mechanisms.[46]

- Profound Personality Transformation in Children

For the youngest children, exposure to violent conflict can produce long-term ill-effects. Healthy emotional development relies upon the infants knowing that they can trust their parents and caregivers to protect them from harm and meet their basic needs, which is the basis for secure attachment and growing independence. But war instills in countless young children, either through the violent death of a parent, through physical injury, or the loss of safe spaces to sleep and play, the fear that nobody, including their parents can in fact protect them, any longer. This can lead to extremes of anxious avoidance or of risk-taking behaviour, as well as to depression, sleeplessness and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder[47]. This in turn impacts upon children’s ability to pursue their needs, for support or resources, later in life, which can in turn impact upon their mental health, creating a vicious cycle of marginalisation. Moreover, for disabled children, the impacts can be amplified, as they are more at risk of abandonment and of losing services essential to meeting their basic, fundamental needs of survival.

- Personal Exploitation of Children and Minors

Many images of war portray children as unintended victims, as ‘collateral’ damage of armed conflict, but interestingly, the fact is that children are often targets during wartime, not only of physical injuries, as observed during the Syrian war, but also at risk of exploitation. Social and state protections are likely to be at their weakest or even totally absent, as in Afghanistan under the Russian invasion in the 1970’s[48], later the al-Qaeda’s grip on Afghanistan [49]by driving the Taliban from power, then enter the Americans; “The War on Terror” [50]of George W. Bush [51] then, presently we have the Taliban[52], with discrimination against girls, based on Islamic Sharia principles.[53] Parents may be killed or injured, or they may be impoverished and unable to protect and provide for their children. In such contexts, children or their caregivers may come to entertain risks they see as preferable to other immediate dangers. This could include pledging a young girl to be married in return for money, imposing an early marriage on a child or accepting the invitation, or financial inducement, of a third party who promises to meet the child’s needs. Often a child will, in this way, become a labourer, or worse, become trafficked, sexually exploited, or sent to fight as a combatant. Targeted kidnappings of children and minors by racketeers, amongst their own communities, to financially profit from the situation, are also common phenomena in such conflict zones.

- Self-blame and the Eternal Guilt in the Minds of Minors

Child soldiers are at particular risk of physical injury and death, but also of sexual and emotional abuse. If they survive the conflict itself, they may be detained as perpetrators rather than victims, compounding the psychosocial impacts of their exploitation. Indeed, child soldiers tend to exhibit more symptoms of mental ill-health than children who have experienced otherwise similar levels of trauma as non-combatants. In this and other kinds of exploitation, it is common for a child to become uncertain about their status as victims, often leading to self-blame, and long years of dealing with unhealthy relationships with themselves and others. This is especially difficult where children have participated in atrocities.

This is a common occurrence in the Syrian War where the ISIS has kidnapped children, trained them as combatants and used them as child soldiers. These minors are exposed, on a daily basis, to the atrocities of warm including killings, beheadings and they eventually they cannot integrate back into the normal society, even with their own parents. The parental dissociation is often transferred to the country of their relocation, such as Canada, by NGO’s involved in Syria, with the kidnapped Yazidi children[54]. The profound personality changes and mental reprogramming has affected these kidnapped minors permanently. The Yazidi children abused by ‘IS’ urgently need help.[55]

They have been liberated from captivity but not from their trauma: Yazidi children, kidnapped, enslaved, abused by “Islamic State,” urgently need help, according to a report by Amnesty International, which throws light on their fate. The genocide of Yazidis by “Islamic State” (IS) will have repercussions for generations to come. The memories are there to stay, not least for some 2,000 children who were freed from IS captivity and returned to their families. These children urgently need help to come to terms with their experience of abuse, humiliation, and indoctrination, Amnesty International wrote in its recent report “Legacy of Terror: The Plight of Yezidi Child Survivors of ISIS,” published on the sixth anniversary of the genocide.

Trauma specialist Jan Kizilhan [57]admits that the plight of the Yazidi children has been overlooked. “So far we were focused on adults rather than youths,” says psychiatrist Jan Ilhan Kizilhan. “We were overwhelmed by the pictures of slavery, rape, mass executions and so the plight of the children was more or less ignored.” Kizilhan heads a center for intercultural psychosomatics in southern Germany. He has interviewed thousands of IS victims, and works with psychotherapists in northern Iraq “because there are simply not enough qualified psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and doctors to cope with the huge number of traumatised adults and children,” says Kizilhan and his team who have spoken with dozens of boys and girls who were abducted by the IS, tortured, exploited or forced into armed combat.[58]- Post-conflict Marginalisation

In an article called ‘When war is better than peace,’ [59]Denov and Lakor write about children born of wartime rape in Uganda, and the stigma they endured in the so-called ‘post-conflict’ period. They describe, “debilitating forms of stigma, violence, socio-economic marginalization, and social exclusion that have a long-term impact their sense of belonging, identity and well-being”. The realities and perspectives of a sample of 60 children born of wartime rape within the Lord’s Resistance Army [60](LRA), and currently living in northern Uganda. These children were born to mothers who were abducted by the LRA, held captive for extended periods of time, repeatedly raped and impregnated.

The multiple challenges that these children face in the post-war period including, rejection, stigma, violence, socio-economic marginalization, and issues of identity and belonging. Participants underscored the profound violence and deprivation that they experienced while in LRA captivity. However, because of post-war marginalisation, participants individually and collectively articulated that wartime was better than peacetime. Multiple systems of support are needed to ensure the rights and protection of these children and importantly, to address and reverse young people’s perceptions that “war is better than peace”.

Early childhood experience accounts for a large part of human brain development. Neural connections for sensory ability, language, and cognitive function are all actively made during the first year for a child.[61] The plasticity and malleability which refer to the flexibility of the brain is highest in the early brain development years. Therefore, the brain can be readily changed by surrounding environments of children. In that sense, children in armed conflict zones may be more susceptible to mental problems such as anxiety and depression, as well as physiological problems in the immune system and central nervous systems.

Stress in early childhood can impede brain development of children that results in both physical and mental health problems.[62] Healthy brain and physical development can be hampered by excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems. Although both adrenaline and cortisol help prepare the body for coping with stressors, when they are used to prolonged and uncontrollable stress, this stress response system can lead to impairments in both mental and physical health.[63]

A child experiencing the trauma of dislocation of the entire family from Myanmar during the Rohingya Genocide. This causes Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, which may be a delayed reaction.

Lack of basic resources may also impede child brain development. Childhood socioeconomic status influences neural development and affects cognitive ability and mental health through adult life.[64] Especially, poverty is regarded to deteriorate cognitive capacity. Many studies have shown that poverty in early childhood can be harmful in that poor families lack time and financial resources to invest in promoting child development.[65] This suggests that the serious deprivation of resources in armed conflict zones is extremely detrimental to cognitive development of children during warfare.

Researchers Okasha and Elkholy in 2012 have theorised that psychological immunization can help children who are frequently exposed to conflict to better acclimate themselves to the stressors of war.[66]

Attachment theory states that children who are detached from a family in early age may go through problems regarding attachment.[67] Children under five are more likely to experience a greater risk of depression and anxiety compared to adolescents. Attachment theory suggests that the ability of a child to create attachment can be deterred by deviant environmental conditions and reflected experiences with caregivers. Different types of attachments can be formed with different caregivers and upbringing environment. In addition, different experiences of attachment in childhood are known to be related to mental health issues in adulthood.[68]

Starved, Malnourished, Cold, Wet, Depressed, Dissociated, Traumatised Children of War. What future do they have?

The Bottom Line is that civil conflicts have been widespread throughout the world in the post-World War II period. During the past decade, economists have analysed the consequences of these conflicts, with particular attention to their welfare effects. The short-run impacts of civil conflicts are clearly catastrophic. However, recent analyses provide mixed evidence on the persistence of the effects of conflict on human capital accumulation, in the long term, particularly on children, in the centre of such inter-statal disharmony, engaged in the conflict zones.[69] Civil conflict is a widespread phenomenon around the world, with about three-fourths of countries having experienced an internal war within the past four decades.[70] The short-term consequences of these conflicts are brutal in terms of lives lost, destruction of economic infrastructure, loss of institutional capacity, deep pain for the families of the people who died in the war and mass population displacements, both internal, as well as external.

There is substantive evidence that war has long- and short-term consequences of political violence on educational achievement in Perú. The empirical literature dealing with the effects of civil conflicts, especially at the macro level, shows robust evidence that those countries exposed to severe violence are able to catch up after a certain period of time, recovering their pre-conflict levels in most development indicators. On the micro side, several papers document the very short-term consequences of conflicts on human development, especially on nutrition and education.

However, if the trends observed at the macro level are followed at the micro level, one might expect these effects to vanish over time. In the Peruvian case, in which the constant struggles between the army and the rebel group PCP-SL lasted over 13 years, causing the death of about 69,290 people. Using a novel data set collected by the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), which registers all the violent acts and fatalities during this period, merged with individual level census data from 1993 and 2007, the results show that the average person exposed to political violence before school age (in-utero, early childhood, and pre-school age ranges) has accumulated 0.31 fewer years of schooling upon reaching adulthood, with stronger short- than long-term effects.

In contrast, individuals who experience the shock after starting school fully catch up to peers who were not exposed to violence. Short-term effects show that the persistence of the shock depends on the moment in life when the child was exposed to violence. The study also confirms that shocks in the pre-birth, in-utero period have a similar effect in the short and long terms. Those exposed during early childhood or pre-school age experience effects that are three times larger in the short-run, while violence exposure once the schooling cycle has started only has a short-term effect. This suggests that children who are affected by violence during the very early childhood, pre-birth-in-utero, suffer irreversible effects of violence.

Those who experience the shock in the early childhood or pre-school age partially recover, while people exposed to violence once they have started their schooling cycle are able to fully catch up with their peers who did not experience violence in this period. This result contrasts with the cross-country findings that the effects of violence vanish over time. Finally, the potential causal mechanisms though which this effect is working, finding suggestive evidence for two of the hypothesized mechanisms. On the supply side, attacks against teachers decrease the educational achievement of children, mainly by delaying school entrance, but this effect is not persistent.

On the demand side, violent events occurring within a year before or after birth decrease the child’s health status. This effect does not seem to go through shocks to household asset tenure, but through maternal health. Overall, the results in this paper contribute to the evidence that shocks during the early stages of one’s life have long-term irreversible consequences on human welfare. This suggests that relief efforts should be targeted to pregnant mothers and young children, and then children in the early stages of their schooling cycle, if we want to minimize the long-term welfare losses for the society.

There is an urgency about ending outright hostilities, the examples quoted remind us that experiences of war can affect children long after wars are over. For this reason, we need to strive to address the causes of violent conflict wherever humanity can, and we pray for peace, because it is children who so often eternally bear the brunt of adults’ failures to negotiate their competing interests, not realising that these disturbed and mal-programmed minors will return, with vengeance to haunt the societies which caused them to become aberrant humanoids.

References:

[i] Personal quote by the author : September 2022

[1] Personal quote by the author : September 2022

[2] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2014/12/30/the-lost-innocence-of-yazidi-children/

[3] https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/young-soldiers-used-in-conflicts-around-the-world/

[4] https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/young-soldiers-used-in-conflicts-around-the-world/

[5] https://www.unicef.org/sowc96/1cinwar.htm

[6] Smith, Deborah (September 2001). “Children in the heat of war”. American Psychological Association.

[7] “Children in war”. United Nations Children’s Fund. Archived from the original on 2018-02-20.

[8] http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php

[9] https://www.unicefusa.org/mission/emergencies/conflict

[10] https://storymaps.esri.com/stories/terrorist-attacks/?year=2017

[11] http://www.newsweek.com/trump-era-record-number-bombs-dropped-middle-east-667505

[12] https://www.unicef.org/french/protection/files/Landmines_Factsheet_04_LTR_HD.pdf

[13] https://www.unicef.org/french/protection/files/Landmines_Factsheet_04_LTR_HD.pdf

[14] http://www.the-monitor.org/media/2615219/Landmine-Monitor-2017_final.pdf

[15] http://www.the-monitor.org/media/2615219/Landmine-Monitor-2017_final.pdf

[16] Guterres A (2017-04-15). “Report of the secretary-general on conflict-related sexual violence” (PDF). United Nations.

[17] https://www.unicef.org/sowc96pk/sexviol.htm

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_of_war_on_children#:~:text=Hick%20S%20(1%20May%202001).%20%22The%20Political%20Economy%20of%20War%2DAffected%20Children%22.%20The%20Annals%20of%20the%20American%20Academy%20of%20Political%20and%20Social%20Science.%20575%20(Sage%20Publications%2C%20Inc.%20in%20association%20with%20the%20American%20Academy%20of%20Political%20and%20Social%20Science)%3A%20106%E2%80%93121.%20doi%3A10.1177/000271620157500107.%20S2CID%C2%A0146478651.

[19] https://archive.org/details/impactofwaronchi0000mach_h2j5

[20] Machel G, Salgado S (2001). The Impact of War on Children: A review of progress since the 1996 United Nations Report on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children. UNICEF. ISBN 978-1-85065-485-8.

[21] Smith, Deborah (September 2001). “Children in the heat of war”. American Psychological Association.

[22] https://www.unicefusa.org/mission/emergencies/food-crises

[23] https://www.unicefusa.org/mission/emergencies/food-crises

[24] Hackman DA, Farah MJ, Meaney MJ (September 2010). “Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research”. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 11 (9): 651–9. doi:10.1038/nrn2897. PMC 2950073. PMID 20725096.

[25] https://archive.org/details/impactofwaronchi0000mach_h2j5

[26] https://archive.org/details/impactofwaronchi0000mach_h2j5

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_of_war_on_children#:~:text=Smith%2C%20Deborah%20(September%202001).%20%22Children%20in%20the%20heat%20of%20war%22.%20American%20Psychological%20Association.%20Archived%20from

[28] http://www.apa.org/monitor/sep01/childwar.aspx

[29] Gennetian LA, Shafir E (2015-09-01). “The Persistence of Poverty in the Context of Financial Instability: A Behavioral Perspective”. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 34 (4): 904–936. doi:10.1002/pam.21854. ISSN 1520-6688

[30] “International Conference on War-Affected Children, Winnipeg, Canada, 10–17 September 2000”. Refugee Survey Quarterly. 23 (2): 287–313. 1 July 2004. doi:10.1093/rsq/23.2.287. ISSN 1020-4067

[31] https://doi.org/10.1093%2Frsq%2F23.2.287

[32] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EDUCATION_FINAL_English.pdf

[33] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EDUCATION_FINAL_English.pdf

[34] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EDUCATION_FINAL_English.pdf

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_of_war_on_children#:~:text=Machel%20G%2C%20Salgado%20S%20(2001).%20The%20Impact%20of%20War%20on%20Children%3A%20A%20review%20of%20progress%20since%20the%201996%20United%20Nations%20Report%20on%20the%20Impact%20of%20Armed%20Conflict%20on%20Children.%20UNICEF.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D85065%2D485%2D8.

[36] https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/11/attacks-schools-aim-destroy-syria-identity-161116092249174.html

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_of_war_on_children#:~:text=Educating%20children%20in%20conflict%20zones%C2%A0%3A%20research%2C%20policy%2C%20and%20practice%20for%20systemic%20change%C2%A0%3A%20a%20tribute%20to%20Jackie%20Kirk.%20Kirk%2C%20Jackie%2C%201968%E2%80%932008.%2C%20Mundy%2C%20Karen%20E.%20(Karen%20Elizabeth)%2C%201962%E2%80%93%2C%20Dryden%2DPeterson%2C%20Sarah.%20New%20York%3A%20Teachers%20College%20Press.%202011.%20ISBN%C2%A09780807752432.%20OCLC%C2%A0730254052.

[38] https://www.unicefusa.org/mission/emergencies/conflict

[39] https://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/article/other/armed-conflict-article-170308.htm

[40] https://web.archive.org/web/20180308103510/https://www.unric.org/en/latest-un-buzz/29639-4-out-of-10-child-soldiers-are-girls

[41] https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/young-soldiers-used-in-conflicts-around-the-world/

[42] http://www.apa.org/monitor/sep01/childwar.aspx

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_of_war_on_children#:~:text=Machel%20G%2C%20Salgado%20S%20(2001).%20The%20Impact%20of%20War%20on%20Children%3A%20A%20review%20of%20progress%20since%20the%201996%20United%20Nations%20Report%20on%20the%20Impact%20of%20Armed%20Conflict%20on%20Children.%20UNICEF.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D85065%2D485%2D8.

[44] https://www.wvi.org/opinion/view/five-surprising-ways-war-can-harm-children

[45] https://repositori.upf.edu/bitstream/handle/10230/19865/1333.pdf;jsessionid=A23EA6DCC96FD8860C67F614C71A5E66?sequence=1

[46] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=e456c5da06385373JmltdHM9MTY2MzM3MjgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTEyOA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lcmljLmVkLmdvdi8_aWQ9RUo5OTk2ODI&ntb=1

[47] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=38ee88e93a2532c6JmltdHM9MTY2MzI4NjQwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTQzNA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cubXNuLmNvbS9lbi16YS9oZWFsdGgvY29uZGl0aW9uL3Bvc3QtdHJhdW1hdGljLXN0cmVzcy1kaXNvcmRlcj9vY2lkPWVudG5ld3NudHA&ntb=1

[48] https://www.britannica.com/event/Soviet-invasion-of-Afghanistan

[49] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Qaeda

[50] https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/ct/rls/wh/6947.htm

[51] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_W._Bush

[52] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taliban

[53] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharia

[54] https://www.npr.org/2020/11/24/938039004/a-yazidi-woman-searches-for-her-lost-daughter-kidnapped-by-isis-6-years-ago

[55] https://www.dw.com/en/yazidi-children/a-54417617

[56] https://www.dw.com/en/yazidi-children/a-54417617#

[57] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=a1fa09eb639c4e43JmltdHM9MTY2MzI4NjQwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE1NQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYWxqYXplZXJhLmNvbS9uZXdzLzIwMTgvNi8xMS9qYW4ta2l6aWxoYW4taXNpbC1yYXBlLXZpY3RpbXMtbmVlZC1jdWx0dXJlLXNlbnNpdGl2ZS10aGVyYXB5&ntb=1

[58] https://www.dw.com/en/yazidi-children/a-54417617#:~:text=Trauma%20specialist%20Jan,into%20armed%20combat.

[59] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0145213417300546

[60] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=c9a56a170088891cJmltdHM9MTY2MzI4NjQwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE3Nw&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvTG9yZCUyN3NfUmVzaXN0YW5jZV9Bcm15&ntb=1

[61] https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/

[62] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impact_of_war_on_children#:~:text=National%20Scientific%20Council%20on%20the%20Developing%20Child.%20(2005/2014).%20Excessive%20Stress%20Disrupts%20the%20Architecture%20of%20the%20Developing%20Brain%3A%20Working%20Paper%203.%20Updated%20Edition.%20http%3A//www.developingchild.harvard.edu%20Archived%202019%2D01%2D09%20at%20the%20Wayback%20Machine

[63] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2005/2014). Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper 3. Updated Edition. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu Archived 2019-01-09 at the Wayback Machine

[64] Mani A, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, Zhao J (August 2013). “Poverty impedes cognitive function”. Science. 341 (6149): 976–80. Bibcode:2013Sci…341..976M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.398.6303. doi:10.1126/science.1238041. PMID 23990553. S2CID 1684186

[65] Duncan GJ, Magnuson K, Votruba-Drzal E (2014). “Boosting family income to promote child development”. The Future of Children. 24 (1): 99–120. doi:10.1353/foc.2014.0008. PMID 25518705. S2CID 14903273

[66] Okasha T, Elkholy H (June 2012). “A synopsis of recent influential papers published in psychiatric journals (2010–2011) from the Arab world”. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 5 (2): 175–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.05.001. PMID 22813663.

[67] Rusby JS, Tasker F (May 2009). “Long-term effects of the British evacuation of children during World War 2 on their adult mental health”. Aging & Mental Health. 13 (3): 391–404. doi:10.1080/13607860902867750. PMID 19484603. S2CID 23781742.

[68] Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Guthrie D (January 2010). “Placement in foster care enhances quality of attachment among young institutionalized children”. Child Development. 81 (1): 212–23. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01390.x. PMC 4098033. PMID 20331663

[69] https://www.bing.com/search?q=the+average+person+accumulates+0.31+less+years+of+education+as+an+adult.+In+the+short-term%2C+the+effects+are+stronger+than+in+the+long-run%3B+these+results+hold+when+comparing+children+within+the+same+household.&cvid=04ac7d6ef82149358117455d0ce549a2&aqs=edge..69i57.23523j0j1&pglt=41&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531

[70] Blattman, Christopher and Edward Miguel (2009). “Civil War”. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(1), 3-57.

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Child Soldiers, Child protection, Children, International Day against the Use of Child Soldiers, Migrant Workers, Migrants, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Refugees, State Terrorism, VAWAC-Violence Against Women and Children

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 19 Sep 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: “Monsters Breed Monsters”: The Impact of Systemic Peace Disruption on Children in Violent Conflict Situations, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.