The Pursuit of Pseudo Peace (Part 1): The Religious Odyssey of Heavenly Bodies on Earth

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 24 Oct 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

This publication is unsuitable for minors in view of the contents. Parental guidance is advised.

“Humanoids are susceptible to lewdness since Genesis, it is an inherent attribute.”[i]

“A sexual scene of a male and a Hetaira[1] prostitute. (an educated female prostitute). Note the money pouch is hanging on the wall. The tondo of an ancient Greek wine cup.

Munich, private collection. 480 – 470 BCE

22 Oct 2022 – This series of publications, discuss the business of prostitution, both male and female throughout history, to highlight how humanoids of both genders pursue the satisfaction of their primitive, carnal desires to achieve inner, pseudo-peace in their daily lives, across the globe. This is attained within the overarching frameworks of different cultures, religions, societal norms and lustful personal pleasure. In most cases while prostitution has been initially engaged in, for economic reasons, to fulfil and unfilled need, it soon becomes a way of life and leads to an addiction. Part 1 reviews the historical aspects of prostitution, highlighting the entity of “Sacred Prostitution” from antiquity, as practiced as a religious ritual, by kings, emperors, religious leaders and nobility of the eras.

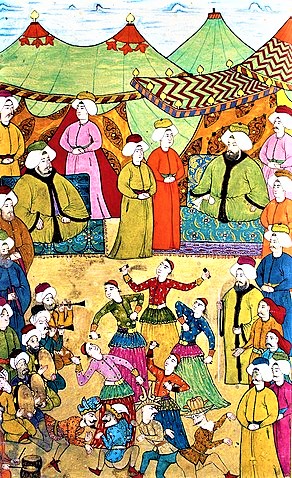

Prostitution has been practiced throughout ancient and modern cultures.[2],[3] Prostitution has been described as “the world’s oldest profession” although the oldest professions are most likely farmers, hunters, and shepherds.[4],[5],[6] Prostitution is defined as the practice of engaging in relatively indiscriminate sexual activity, in general with someone who is not a spouse or a friend, in exchange for immediate payment in money or other valuables, relevant to the period in which this act of acceptable social transgression was committed. Prostitutes may be female or males as evidences since the Middle Ages in the Köçek troupe at a fair. Recruited from the ranks of colonized ethnic groups, Köçeks were entertainers and sex workers in the Ottoman empire. These were males, dressed as and impersonating females, for the sexual pleasure of some men in pursuit of pseudo-peace within themselves.

Middle Ages, Köçek troupe at a fair, recruited from the ranks of colonised ethnic groups. Köçeks were entertainers and sex workers in the Ottoman empire.

Prostitution was practiced as a religious ritual in the Antiquity, as well. The Ancient Near East was home to many shrines, temples, or “houses of heaven,” which were dedicated to various deities. These shrines and temples were documented by the Greek historian Herodotus in The Histories,[7] where sacred prostitution was a common practice.[8] Sacred prostitution has many different characteristics depending on the region, class and the religious ideals of the period and the place, consequently can have many different definitions. One definition that was developed was due to the common types of sacred prostitution that are recorded in Classical sources: sale of a woman’s virginity or rinni in honor of a goddess or a once-in-a-lifetime prostitution, professional prostitutes or slaves owned a temple or sanctuary, and temporary prostitution that occurs before a marriage or during certain rituals.[9] Stephanie Budin offers her own definition while trying to argue that sacred prostitution never existed: “Sacred prostitution is the sale of a person’s body for sexual purposes where some portion, if not all, of the money or goods received for this transaction belongs to a deity”.[10]

Sumerian records dating back to ca. 2400 BCE are the earliest recorded mention of prostitution as an occupation. These describe a temple-brothel operated by Sumerian priests in the city of Uruk. This kakum or temple was dedicated to the Sumerian goddess of sexual love, fertility, and warfare, later called Goddess Ishtar and was the home to three grades of women. The first grade of women was only permitted to perform sexual rituals in the temple, the second group had access to the grounds and catered to visitors, and the third and lowest class lived on the temple grounds. These women were also free to solicit clients in the streets. Through the 20th century, scholars generally believed that a form of sacred marriage rite, hieros gamos, was staged between the kings in the ancient Near Eastern region of Sumer and the high priestesses of Inanna. The king would couple with the priestess to represent the union of Dumuzid with Inanna.[11] According to the noted Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer, the kings would further establish their legitimacy by taking part in a ritual sexual act in the temple of the fertility with Goddess Ishtar, every year on the tenth day of the New Year festival Akitu.[12]

Inanna/Ishtar, is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility, depicted on a ceremonial vase. Inanna She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Sumer under the name “Inanna”, and later by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians as Ishtar. Picture credit: Louvre, Paris

According to Herodotus, the rites performed at these temples included sexual intercourse, or what scholars later called sacred sexual rites. In modernity, the foulest Babylonian custom is that which compels every woman of the land to sit in the temple of Aphrodite and have intercourse with some stranger. at least once in her life. Many women who are rich, proud and disdain to mingle with the rest, drive to the temple in covered carriages drawn by teams, and stand there with a great retinue of attendants. But most sit down in the sacred plot of Aphrodite, with crowns of cord on their heads; there is a great multitude of women coming and going; passages marked by line run every way through the crowd, by which the men pass and make their choice. Once a woman has taken her place there, she does not go away to her home before some stranger has cast money into her lap, and had intercourse with her outside the temple; but while he casts the money, he must say, “I invite you in the name of Mylitta”. It does not matter what sum the money is; the woman will never refuse, for that would be a sin, the money being by this act made sacred. The chosen lady follows the first man who casts it and rejects no one. After their intercourse, having discharged her sacred duty to the goddess, she goes away to her home; and thereafter there is no bribe however great that will get her. So then the women that are fair and tall are soon free to depart, but the uncomely have long to wait because they cannot fulfil the law; for some of them remain for three years, or four. There is a custom like this in some parts of Cyprus.[13]

The British anthropologist James Frazer accumulated citations to prove this in a chapter of his magnum opus The Golden Bough (1890–1915),[14] and this has served as a starting point for several generations of scholars. Frazer and Henriques distinguished two major forms of sacred sexual rites: temporary rite of unwed girls, with variants such as dowry-sexual rite, or as public defloration of a bride, and lifelong sexual rite.[15] However, Frazer took his sources mostly from authors of Late Antiquity (i.e. 150–500 AD), not from the Classical or Hellenistic periods.[16] This raises questions as to whether the phenomenon of temple sexual rites can be generalised to the whole of the ancient world, as earlier scholars typically did. In Hammurabi’s code of laws, the rights and good name of female sacred sexual priestesses were protected. The same legislation that protected married women from slander applied to them and their children. They could inherit property from their fathers, collect income from land worked by their brothers, and dispose of property. These rights have been described as extraordinary, considering the role of women at the time.[17] There were specific terms associated with temple prostitution in Sumeria and Babylonia. All translations are sourced from the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary.[18] Akkadian terms were used in the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, and Babylonia. The terms themselves come from lexical profession lists on tablets dating back to the Early Dynastic period.

It has been argued that sacred prostitution, worked by both males and females, was a custom of ancient Phoenicians.[19] It would be dedicated to the deities Astarte and Adonis, and sometimes performed as a festival or social rite in the cities of Byblos, Afqa and Baalbek, later named Heliopolis[20] as well as the nearby Syrian city of Palmyra.[21] At the Etruscan site of Pyrgi, a center of worship of the eastern goddess Astarte, archaeologists identified a temple consecrated to her and built with at least 17 small rooms that may have served as quarters for temple prostitutes.[22] Similarly, a temple dedicated to her equated goddess Atargatis in Dura-Europos, was found with nearly a dozen small rooms with low benches, which might have used either for sacred meals or sacred services of women jailed in the temple for adultery.[23] Pyrgi’s sacred prostitutes were famous enough to be apparently mentioned in a lost fragment of Lucilius’s works.[24] In northern Africa, the area of influence of the Phoencian colony of Carthage, this service was associated to the city of Sicca, a nearby city that received the name of Sicca Veneria for its temple of Astarte or Tanit, called Venus by Roman authors.[25] Valerius Maximus describe how their women gained gifts by engaging in prostitution with visitors.[26]

Phoenicio-Punic settlements in Hispania, like Cancho Roano, Gadir, Castulo and La Quéjola, have suggested this practice through their archaeology and iconography. In particular, Cancho Roano features a sanctuary built with multiple cells or rooms, which has been identified as a possible place of sacred prostitution in honor to Astarte.[27] A similar institution might have been found in Gadir. Its posterior, renowned erotic dancers called puellae gaditanae in Roman sources, or cinaedi in the case of male dancers, might have been desecrated heirs of this practice, considering the role occupied by sex and dance on Phoenician culture.[28] Another center of cult to Astarte was Cyprus, whose main temples were located in Paphos, Amathus and Kition.[29] The epigraphy of the Kition temple describes personal economic activity on the temple, as sacred prostitution would have been taxed as any other occupation, and names possible practitioners as grm (male) and lmt (female).[30]

In the region of Canaan, a significant portion of temple prostitutes was males. This was also widely practiced in Sardinia and in some of the Phoenician cultures, usually in honor of the Goddess Ashtart. Presumably under the influence of the Phoenicians, this practice was developed in other ports of the Mediterranean Sea. In later years sacred prostitution and similar classifications for females were known to have existed in Greece, Rome, India, China, and Japan.[31] Such practices came to an end when the emperor Constantine in the 320s AD destroyed the goddess temples and replaced the religious practices with principles of Christianity.[32] In India, the Devadasi girls are forced by their poor families to dedicate themselves to the Hindu goddess Renuka, the Goddess of fertility. The BBC wrote in 2007 that devadasis are “sanctified prostitutes.”[33]

The Biblical references, highlight prostitution as commonplace trade in ancient Israel. There are a number of references to prostitution in the Hebrew Bible. The Biblical story of Judah and Tamar (Genesis 38:14–26) provides a depiction of prostitution being practiced in that time period. In this particular narration, the prostitute waits at the side of a highway for travelers. As was the custom, the lady covers her face in order to identify herself as a prostitute. Instead of being remunerated financially, she asks for a kid goat. This would have been the equivalent of a high price at the time, indicating, that only the wealthy owner of numerous herds could have afforded to pay for a single sexual encounter. In this business system, if the traveler does not have his cattle with him, at the time of the transaction, he must give valuables to the woman, as a deposit, until a kid goat is delivered to her, with the return of the deposit, as mutually agreed. The woman in the Biblical story was not a legitimate prostitute, but was in real life, was Judah’s widowed daughter-in-law, who sought to trick Judah into impregnating her. However, since she succeeded in impersonating a prostitute, during that era, her general social conduct, can be assumed to accurately represent the behaviour of a prostitute in society during that Biblical period.

In a later Biblical story, found in the Book of Joshua, a prostitute in Jericho named Rahab assisted Israelite spies by providing them with information regarding the current socio-cultural and military situation. Rahab was knowledgeable in these matters because of her popularity with the high-ranking nobles. The Israelite spies, in return for this information, promised to save her and her family during the planned military invasion, only if she kept the details of her contact with them a secret. She would leave a sign on her residence that indicated to the advancing soldiers not to attack the people within. When the people of Israel conquered Canaan, she converted to Judaism and married a prominent member of the people.

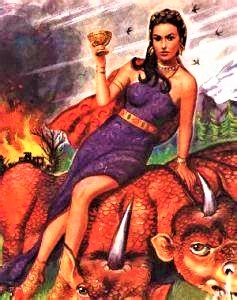

In the Book of Revelation, the Whore of Babylon is named “Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth”. However, the word “whore” could also be translated as “idolatress”.[34],[35]

The Hebrew Bible uses two different words for prostitute, zonah and kedeshah.[36] The word zonah simply meant an ordinary prostitute or loose woman.[37] But the word kedeshah literally means set apart, in feminine form, from the Semitic root Q-D-Sh, meaning holy, consecrated or set apart. Nevertheless, zonah and qedeshah are not interchangeable terms: the former occurs 93 times in the Bible,[38] whereas the latter is only used in three places,[39] conveying different connotations. This double meaning has led to the belief that kedeshah were not ordinary prostitutes, but sacred harlots who worked out of fertility temples.[40] However, the lack of solid evidence[41] has indicated that the word might refer to prostitutes who offered their services in the vicinity of temples, where they could attract a larger number of clients. The term might have originated as consecrated maidens employed in Canaanite and Phoenician temples, which became synonymous with harlotry for Biblical writers.[42] In any case, the translation of sacred prostitute has continued, however, because it explains how the word can mean such disparate concepts as sacred and prostitute.[43] As put by DeGrado, “neither the interpretation of the as a “priestess-not-prostitute”, according to Westenholz nor as a “prostitute-not-priestess”, according to Gruber, adequately represents the semantic range of Hebrew word in biblical and post-biblical Hebrew.”[44] Male prostitutes were called kadesh or qadesh, literally: male who is set apart.[45] The Hebrew word kelev (dog) may also signify a male dancer or prostitute.[46]

The Law of Moses, Deuteronomy, was not universally observed in Hebrew culture under the rule of King David’s dynasty, as recorded in Kings. In fact Judah had lost “the Book of the Law”. During the reign of King Josiah, the high priest Hilkiah discovers it in “the House of the Lord” and realizes that the people have disobeyed, particularly regarding prostitution.[47] Examples of male prostitution being banned under King Josiah are recorded to have been commonplace since the reign of King Rehoboam of Judah, King Solomon’s son.[48]

Most Bible translations do not reflect the latest scholarship and modern translations refer to King Josiah’s bans on “male temple prostitutes” or similarly “male shrine prostitutes”, whereas older translations refer to the ban of “Sodomites” and “the Houses of the Sodomites”. Under the uncentralised religious practices that were commonplace, homosexual prostitution experienced a degree of cultural acceptance along with heterosexual prostitution among the Hebrew tribes, but under the religious reforms, prostitution was not allowed in conjunction with the worship of Yahweh, where these had been expressly forbidden in Deuteronomy, their sacred Book of Law under King Josiah.[49]

None of the daughters of Israel shall be a kedeshah, nor shall any of the sons of Israel be a kadesh. You shall not bring the hire of a prostitute (zonah) or the wages of a dog (kelev) into the house of the Lord your God to pay a vow, for both of these are an abomination to the Lord your God. In the Book of Ezekiel, Oholah and Oholibah appear as the allegorical brides of God who represent Samaria and Jerusalem. They became prostitutes in Egypt, engaging in prostitution from their youth. The prophet Ezekiel condemns both as guilty of religious and political alliance with heathen nations.[50]

In ancient Greece, sacred prostitution was known in the city of Corinth where the Temple of Aphrodite employed a significant number of female servants, “hetairai”, during classical antiquity.[51] The Greek term hierodoulos or hierodule has sometimes been taken to mean sacred holy woman, but it is more likely to refer to a former slave freed from slavery in order to be dedicated to a god. There were different levels of prostitutes within Ancient Greece society, but two categories are specifically related to sacred or temple prostitution. The first category are hetaires, also known as courtesans, typically more educated women that served within temples. The second category are known as hierodoules, slave women or female priests who worked within temples and served the sexual requests of visitors to the temple.[52]

While there may not be a direct connection between temples and prostitution, many prostitutes and courtesans worshipped Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Prostitutes would use their earnings to pay for dedications and ritualistic celebrations in honor of Aphrodite. Some prostitutes also viewed the action of sexual service and sexual pleasure as an act of devotion to the goddess of love, worshipping Aphrodite through an act rather than a physical dedication.[53] In the temple of Apollo at Bulla Regia, a woman was found buried with an inscription reading: “Adulteress. Prostitute. Seize, because I fled from Bulla Regia.” It has been speculated she might be a woman forced into sacred prostitution as a punishment for adultery.[54] The act of sacred prostitution within the Temples of Aphrodite in the city of Corinth were well-known and well-spread. Greek writer-philosopher Strabo comments, “the Temple of Aphrodite was so rich that it owned a thousand temple-slaves, courtesans, whom both men and women had dedicated to the goddess”. Within the same work, Strabo compares Corinth to the city of Comana, confirming the belief that temple prostitution was a notable characteristic of Corinth. Prostitutes performed sacred functions within the temple of Aphrodite. They would often burn incense in honor of Aphrodite. Chameleon of Heracleia recorded in his book, “On Pindar”, that whenever the city of Corinth prayed to Aphrodite in manners of great importance, many prostitutes were invited to participate in the prayers and petitions.[55] The girls involved in temple prostitution were typically slaves owned by the temple. However, some of the girls were gifted to the temple from other members of society in return for success in particular endeavou rs. One example that shows the gifting of girls to the temple is the poem of Athenaeus, which explores an athlete Xenophon’s actions of gifting a group of courtesans to Aphrodite as a thanks-offering for his victory in a competition. Specifically in 464 BC, Xenophon was victorious in the Olympic Games and donated 100 slaves to Aphrodite’s temple. Pindar, a famous Greek poet, was commissioned to write a poem that was to be performed at Xenophon’s victory celebration in Corinth. The poet acknowledged that the slaves would serve Aphrodite as sacred prostitutes within her temple at Corinth.[56]

Another temple of Aphrodite was named Aphrodite Melainis, located near the city gates in an area known as “Craneion”. It is the resting place of Lais, who was a famous prostitute in Greek history. This suggests that there was a connection with ritual prostitution within temples of Aphrodite. There is a report that was found of an epigram of Simonides commemorating the prayer of the prostitutes of Corinth on behalf of the salvation of the Greeks from the invading Persians in early 5th century BCE. Both temple prostitutes and priestesses prayed to Aphrodite for help, and were honored for their potent prayers, which Greek citizens believed contributed to the repelling of the Persians.[57] Athenaeus also alludes to the idea that many of Aphrodite’s temples and sanctuaries were occupied by temple prostitutes. These prostitutes were known to practice sexual rituals in different cities which included Corinth, Magnesia, and Samos.[58]

Some evidence of sacred prostitution was evident in Minoan Crete. The building in question is known as the “East Building”, but was also referred to as “the House of the Ladies” by the excavator of the building. Some believe that the architecture of this building seemed to reflect the grooming needs of women, but could also have been a brothel for high status individuals.[59]

The structure of the interior of the building seemed to suggest that the building was used for prostitution. Large clay vats typically used for bathing were found within the building, along with successive doors within the corridors. The successive doors suggested privacy, and within the time period, was associated with two functions: storage of valuable goods and protection of the private moments of its residents. Because the ground floors were found practically empty, the possibility that the building was used for prostitution increases.[60]

There were also religious embellishments found within the “East Building”, such as vases and other vessels that seemed to be connected to religious rituals. The vessels were covered in motifs related to sacrilegious rituals, such as the sacral knot and the image of birds flying freely. The functions of the vessels would have been offering food or liquid in relation to the rituals. Combining these two factors together, it is a possibility that sacred prostitution existed within this building.[61]

In the Greek-influenced and colonized world, “sacred prostitution” was known in Cyprus[62] (Greek-settled since 1100 BC), Sicily[63] (Hellenized since 750 BC), in the Kingdom of Pontus[64] (8th century BC) and in Cappadocia (c. 330 BC hellenized).[65] 2 Maccabees 6:4–5 describes sacred prostitution in the Hebrew temple under the reign of the Hellenistic ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes. A passage in Herodotus explains a Babylonian custom where before marriage, girls had to offer themselves for sex, presumably within a temple, as required by rites of a goddess equivalent to Aphrodite in their culture. Herodotus records that a similar practice or custom took place within Cyprus, with girls offering themselves up for sex as required by the rites of Aphrodite.[66] Ennius and Ovid corroborate each other on the idea that Aphrodite established the act of prostitution within the city of Cyprus. A temple of Kition also shows evidence of sacred prostitution. On a marble plaque, it lists out sacred prostitutes among other professions (bakers, scribes, barbers) that were part of ritual personnel at some Cypriot temples.[67]

The temple of Aphaca may be another source of evidence for temple prostitution.[68] The process is similar to regular prostitution, where male customers paid two or three obols in the form of, or in addition to dedications to Aphrodite in exchange for sex with a temple prostitute. In the temple of Aphaca specifically, the men would dedicate their payment to “Cyprian Aphrodite” before engaging in sex with a temple prostitute.

In late antiquity, the first, Christian, Roman Emperor Constantine closed down a number of temples to Venus or similar deities in the 4th century AD, as the Christian church historian Eusebius proudly noted. Eusebius also claimed that the Phoenician cities of Aphaca and Heliopolis (Baalbek) continued to practise temple prostitution until the Emperor Constantine put an end to the rite in the 4th century AD.[69]

This culture of sacred prostitution was world-wide, practiced in Jan, India and the Americas. The Maya maintained several phallic religious cults, possibly involving homosexual temple prostitution.[70] Much evidence for the religious practices of the Aztec culture was destroyed during the Spanish conquest, and almost the only evidence for the practices of their religion is from Spanish accounts. The Franciscan Spanish Friar Bernardino de Sahagún learned their language and spent more than 50 years studying the culture. He wrote that they participated in religious festivals and rituals, as well as performing sexual acts as part of religious practice. This may be evidence for the existence of sacred prostitution in Mesoamerica, or it may be either confusion, or accusational polemic. He also speaks of kind of prostitutes named ahuianime (“pleasure girls”), whom he described as “an evil woman who finds pleasure in her body… a dissolute woman of debauched life.”[71]

Statue of Xochipilli, Aztec god of art, games, dance, flowers, and song. Approved patron of homosexuals and homosexual prostitutes.

It is agreed that the Aztec god Xochipili (taken from both Toltec and Maya cultures) was both the patron of homosexuals and homosexual prostitutes.[72] Xochiquetzal was worshiped as goddess of sexual power, patroness of prostitutes and artisans involved in the manufacture of luxury items.[73]

The Incas, also dedicated young boys as temple prostitutes. The boys were dressed in girl’s clothing, and chiefs and head men would have ritual sexual intercourse with them during religious ceremonies and on holy days.[74]

The Bottom Line, in summary, is that in late antiquity prostitution in ancient Rome, which was a mighty empire, set the standards of acceptable social behavioural patterns and norms, whereby officially practised and encouraged prostitution and religion, were intertwined. This was the hallmark of paganism where devotion to gods and goddesses were of paramount importance and offerings of scared prostitution were made in return for favours granted during the course of wars and other aspects of daily lives. Prostitution was also an integral part of fertility rites, esprecially in barren women and impotent men, as a mechanism to seek pseudo-peace. These practices were dramatically chaged with the advent of the Abrahamic religions and life was conducted according to the different scriptures, in Judiasm, Christianity and Islam. It is also ironic that severe punishments were meted out to adulteresses while, at the same time, sacred prostitution was officially practised. The rational explanation for thie anomaly, in the male dominated patriarchal society is that these males are entitled to the pursuit of inner peace, be it a pseudo peace, by engaging in sexual activities with an entire galaxy of females, including the priests given the privilege of performing sexual acts with virgins and deflower these young maidens, prior to their marriage. These naïve girls were encouraged to offer themselves into sacred prostitution, under the guise of appeasing the pagan gods, at the time.

According to Avaren Ipsen, from University of California, Berkeley’s Commission on the Status of Women, the myth of sacred prostitution works as “an enormous source of self-esteem and as a model of sex positivity” to many sex workers.[75] She compared this situation to the figure of Mary Magdalene, whose status as a prostitute, though short-lived according to Christian texts and disputed among academics, has been celebrated by sex working collectives, among them Sex Workers Outreach Project USA, in an effort to de-stigmatize their job. Ipsen speculated that academic currents trying to deny sacred prostitution are ideologically motivated, attributing them to the “desires of feminists, including myself, to be ‘decent.”

In her book, The Sacred Prostitute: Eternal Aspect of the Feminine, psychoanalyst Nancy Qualls-Corbett praised sacred prostitution as an expression of female sexuality and a bridge between the latter and the divine, as well as a rupture from mundane sexual degradation. “The sacred prostitute did not make love in order to obtain admiration or devotion from the man who came to her… She did not require a man to give her a sense of her own identity; rather this was rooted in her own womanliness.”[76] Qualls also equated censuring sacred prostitution to demonize female sexuality and vitality. “In her temple, men and women came to find life and all that it had to offer in sensual pleasure and delight. But with the change in cultural values and the institutionalisation of monotheism and patriarchy, the individual came to the House of God to prepare for death.”[77]

This opinion is shared by several schools of modern Paganism.[78] among them Wicca,[79] for whom sacred prostitution, independently from its historical backing, embodies the sacralisation of sex and a celebration of the communion between female and male sexuality. This practice is associated to spiritual healing and sex magic. Within secular thinking, philosopher Antonio Escohotado is a popular adept of this current, favouring particularly the role of ancient sacred prostitutes and priestesses of Ishtar. In his seminal work Rameras y esposas, he extols them and their cult as symbols of female empowerment and sexual freedom.[80]

Based on this historical background, some modern sacred prostitutes also act as sexual surrogates as a form of therapy. In places where prostitution is illegal, sacred prostitutes may be paid as therapists, escorts, or performers.[81]

References:

[i] Personal quote by the author, October 2022.

[1] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=532f36456b4aec08JmltdHM9MTY2NjM5NjgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE1OA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Hetaira+prostitute&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvSGV0YWlyYQ&ntb=1

[2] Jenness, Valerie (1990). “From Sex as Sin to Sex as Work: COYOTE and the Reorganization of Prostitution as a Social Problem,” Social Problems, 37(3), 403-420. “Prostitution has existed in every society for which there are written records”

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_prostitution#CITEREFBulloughBullough1978

[4] https://san-jose-criminal-defense-law.com/thoughts-prostitution-worlds-oldest-profession/

[5] Strong, Anise K. (2016). “Prostitutes and matrons in the urban landscape”. Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 142–170. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316563083.007. ISBN 9781316563083.

[6] Keegan, Anne (1974). “World’s oldest profession has the night off,” Chicago Tribune, July 10. New World Encyclopedia

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_prostitution#:~:text=Herodotus%2C%20The%20Histories%201.199%2C%20tr%20A.D.%20Godley%20(1920)

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_prostitution#:~:text=See%2C%20for%20example%2C%20James%20Frazer%20(1922)%2C%20The%20Golden%20Bough%2C%203e%2C%20Chapter%2031%3A%20Adonis%20in%20Cyprus

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Pirenne%2DDelforge%2C%20Vinciane%20(2009).%20%22Review%20of%20St.%20L.%20Budin%2C%20The%20myth%20of%20sacred%20prostitution%20in%20Antiquity%22.%20Bryn%20Mawr%20Classical%20Review.

[10] Budin 2008; more briefly the case that there was no sacred prostitution in Greco-Roman Ephesus Baugh 1999; see also the book review by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, April 28, 2009.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFDay2004

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=%5E-,Kramer%201969.,-%5E%20Frazer%201922

[13] https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hdt.+1.199

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Frazer%201922%2C%20abridged%20ed.%20Chapter%2031%3A%20Adonis%20in%20Cyprus%3B%20see%20also%20the%20more%20extensive%20treatment%20Frazer%201914%2C%203rd%20ed.%20volumes%205%20and%206.%20Frazer%27s%20argument%20and%20citations%20are%20reproduced%20in%20slightly%20clearer%20fashion%20by%20Henriques%201961%2C%20vol.%20I%2C%20ch.%201

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Henriques%201961%2C%20vol.%20I%2C%20ch.%201.

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herodotus

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFQualls-Corbett1988

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=University%20of%20Pennsylvania.%20%22Pennsylvania%20Sumerian%20Dictionary%22.%20Pennsylvania%20Sumerian%20Dictionary.%20University%20of%20Pennsylvania.%20Retrieved%2012%20June%202020.

[19] Teresa Moneo, Religio iberica: santuarios, ritos y divinidades (siglos VII-I A.C.), 2003, Real Academia de la Historia, ISBN 9788495983213

[20] Biblical Archaeology Society Staff, Sacred Prostitution in the Story of Judah and Tamar?, 7 August 2018

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Jos%C3%A9%20Mar%C3%ADa%20Bl%C3%A1zquez%20Mart%C3%ADnez%2C%20La%20diosa%20de%20Chipre%2C%20Real%20Academia%20de%20la%20Historia.%20Saitabi.%20Revista%20de%20la%20Facultat%20de%20Geografia%20i%20Hist%C3%B2ria%2C%2062%2D63%20(2012%2D2013)%2C%20pp.%2039%2D50

[22] https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-israel/sacred-prostitution-in-the-story-of-judah-and-tamar/

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFLipi%C5%84ski2013

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universidad_de_Sevilla

[25] Ana María Jiménez Flores, Cultos fenicio-púnicos de Gádir: Prostitución sagrada y Puella Gaditanae, 2001. Habis 32. Universidad de Sevilla.

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Valerius%20Maximus%2C%20Factorum%20et%20dictorum%20memorabilium%20libri%20novem%2C%20II.%206.15

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/9788495983213

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Guadalupe%20L%C3%B3pez%20Monteagudo%2C%20Mar%C3%ADa%20Pilar%20San%20Nicol%C3%A1s%20Pedraz%2C%20Astart%C3%A9%2DEuropa%20en%20la%20pen%C3%ADnsula%20ib%C3%A9rica%20%2D%20Un%20ejemplo%20de%20interpretatio%20romana%2C%20Complurum%20Extra%2C%206(I)%2C%201996%3A%20451%2D470

[29] Teresa Moneo, Religio iberica: santuarios, ritos y divinidades (siglos VII-I A.C.), 2003, Real Academia de la Historia, ISBN 9788495983213

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Julio%20Gonz%C3%A1lez%20Alcalde%2C%20Simbolog%C3%ADa%20de%20la%20diosa%20Tanit%20en%20representaciones%20cer%C3%A1micas%20ib%C3%A9ricas%2C%20Quad.%20Preh.%20Arq.%20Cast.%2018%2C%201997

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_prostitution#CITEREFMurphy1983

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_prostitution#:~:text=Eusebius%2C%20Life%20of%20Constantine%2C%203.55%20and%203.58

[33] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6729927.stm

[34] http://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?strongs=G4204

[35] https://books.google.com/books?id=jNJeDZKqpQ4C&pg=PA79&lpg=PA79&dq=biblical+%22whore%22+or+%22idolatress%22&source=bl&ots=6R7_RSP3fJ&sig=j-LnajPgBAhOjAEc7DwjGhHESCY&hl=en&ei=j9WyTqj6I4mtsQKBt-WABA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CDAQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=biblical%20%22whore%22%20or%20%22idolatress%22&f=false

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Associated%20with%20the,be%20k%27deysha.

[37] Associated with the corresponding verb zanah.”Genesis 1:1 (KJV)”. Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 5 April 2018. incorporating Strong’s concordance (1890) and Gesenius’s Lexicon (1857). Also transliterated qĕdeshah, qedeshah, qědēšā ,qedashah, kadeshah, kadesha, qedesha, kdesha. A modern liturgical pronunciation would be k’deysha.

[38] https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?t=kjv&strongs=h2181

[39] https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?t=kjv&strongs=h6948

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFGrossman_et_al2011

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFYamauchi1973

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFLipi%C5%84ski2013

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFLipi%C5%84ski2013

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFDeGrado2018

[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFGruber1986

[46] https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?t=kjv&strongs=h3611

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFSweeney2001

[48] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=1%20Kings%2014%3A24%2C%201%20Kings%2015%3A12%20and%202%20Kings%2023%3A7

[49] https://www.biblica.com/bible/?osis=niv:Deuteronomy%2023:17%E2%80%9318

[50] http://classic.net.bible.org/dictionary.php?word=OHOLIBAH

[51] https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/8F*.html

[52] SOUCALAS, Gregory; MICHALEAS, Spyros; ANDROUTSOS, Georges; VLAHOS, Nikolaos; KARAMANOU, Marianna (2021). “Female prostitution, hygiene, and medicine in ancient Greece: A peculiar relationship”. Archives of the Balkan Medical Union. 56 (2): 229–233. doi:10.31688/ABMU.2021.56.2.12. S2CID 237858610.

[53] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Cyrino%2C%20Monica%20Silveira%20(2012).%20Aphrodite.%20Routledge.%20ISBN%C2%A09781136615917

[54] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/9788495983213

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Strong%2C%20Rebecca%20(1997).%20The%20most%20Shameful%20Practice%3A%20Temple%20Prostitution%20in%20the%20Ancient%20Greek%20World.%20University%20of%20California%2C%20Los%20Angeles.%20pp.%C2%A074%E2%80%9375.

[56] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Blegen%2C%20C.%20%22THE%20CORINTHIAN%20GODDESS%3A%20Aphrodite%20and%20Her%20Hierodouloi.%22

[57] Blegen, C. “THE CORINTHIAN GODDESS: Aphrodite and Her Hierodouloi.”

[58] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Manning%2C%20W.%20%E2%80%9CThe%20Double%20Tradition%20of%20Aphrodite%E2%80%99s%20Birth%20and%20Her%20Semitic%20Origins%E2%80%9D.%20Scripta%20Mediterranea%2C%20vol.%2023%2C%20Mar.%202015%2C%20https%3A//scripta.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/scripta/article/view/40023.

[59] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=%5E-,Platon%2C%20Lefteris%20(2015).%20%22Sacred%20Prostitution%20in%20Minoan%20Crete%3F%20A%20New%20Interpretation%20of%20Some%20Old%20Archaeological%20Findings%22.%20Journal%20of%20Ancient%20Egyptian%20Interconnections.%207%20(3)%3A%2076%E2%80%9389.%20doi%3A10.2458/azu_jaei_v07i3_platon.,-%5E

[60] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=%5E-,Platon%2C%20Lefteris%20(2015).%20%22Sacred%20Prostitution%20in%20Minoan%20Crete%3F%20A%20New%20Interpretation%20of%20Some%20Old%20Archaeological%20Findings%22.%20Journal%20of%20Ancient%20Egyptian%20Interconnections.%207%20(3)%3A%2076%E2%80%9389.%20doi%3A10.2458/azu_jaei_v07i3_platon.,-%5E

[61] Platon, Lefteris (2015). “Sacred Prostitution in Minoan Crete? A New Interpretation of Some Old Archaeological Findings”. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 7 (3): 76–89. doi:10.2458/azu_jaei_v07i3_platon.

[62] http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20161017-it-was-an-ancient-form-of-sex-tourism

[63] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Stupia%2C%20Tiziana.%20%22Salome%20re%2Dawakens%3A%20Beltane%20at%20the%20Temple%20of%20Venus%20in%20Sicily%20%E2%80%93%20Goddess%20Pages%22.%20goddess%2Dpages.co.uk.%20Retrieved%2025%20August%202019.

[64] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=%5E-,Debord%201982%2C%20p.%C2%A097.,-%5E%20Yarshater%201983

[65] Yarshater, Ehsan (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521200929.

[66] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Herodotus%2C%20History.%20Rawlinson%2C%20G.%20(trans.)%2C%20New%20York%3A%20Tudor%20Publishing%20Company%2C%201936

[67] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Serwint%2C%20Nancy.%20%22Aphrodite%20and%20her%20Near%20Eastern%20sisters%3A%20spheres%20of%20influence.%22%20Engendering%20Aphrodite%3A%20Women%20and%20Society%20in%20Ancient%20Cyprus%2C%20American%20Schools%20of%20Oriental%20Research%2C%20Boston%20(2002)%3A%20325%2D350.

[68] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#:~:text=Gibson%2C%20Craig%20(2019).%20%22Temple%20Prostitution%20at%20Aphaca%3A%20An%20Overlooked%20Source%22.%20Classical%20Quarterly.%2069%20(2)%3A%20928%E2%80%93931.%20doi%3A10.1017/S0009838819000697.%20S2CID%C2%A0211942060.

[69] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eusebius

[70] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFGreenberg1988

[71] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFBernardino_de_Sahag%C3%BAn1982

[72] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFTrexler1995

[73] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFSmith2003

[74] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFFlornoy1958

[75] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFIpsen2014

[76] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFQualls-Corbett1988

[77] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFQualls-Corbett1988 p43

[78] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFPike2004

[79] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFHolland2008

[80] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFEscohotado2018

[81] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution#CITEREFHunter2006

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: History, Homosexuality, Prostitution, Religion, Sex, Sexism, Sexualities

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 24 Oct 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Pursuit of Pseudo Peace (Part 1): The Religious Odyssey of Heavenly Bodies on Earth, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.