In the second dream, Esquire wanted to interview Ginsberg “for a feature article on [his] divine person.” Ginsberg called his friend William S. Burroughs to share the news, but Burroughs disapproved, telling Ginsberg he’d been vain and stupid to accept the invitation. Ginsberg felt “chagrined,” and woke up. Next, he was headed toward San Francisco in the Volkswagen. A poem earnestly titled “Beginning of a Poem of These States” tracks his journey. Ginsberg records the character and color of the landscape, the tinny pandemonium on the radio, the Beach Boys singing tenderly against a backdrop of new industrial farmlands spreading; he suggests that his tennis shoes from Central Europe are not thick enough to keep his feet from getting cold in the early mornings.

What else do you want to know? Ginsberg’s life has been exhaustively catalogued by multiple encyclopedic biographies. But his experience of the late sixties is knowable in especially fine detail—a consequence of his efforts in those years to make the work of writing and self-documentation as mobile, flexible, and constant as possible. His poetry began to resemble a travel log, attaching particular experiences to particular places. In “Beginning of a Poem of These States,” he describes the morning sun warming his feet, ravens landing on a dead cow at the side of the road, tomato sandwiches, silence. Through California’s Donner Pass, the poem’s speaker feels a surge of giddy freedom; “I have nothing to do,” he says, “laughing.” Wildfire smoke forms a purple band at the horizon, and the speaker chants to the Hindu god Shiva—a “new mantra to manifest Removal of Disaster from my self.” As an unnaturally red sun sets over California, Bob Dylan’s “Positively 4th Street” comes on the radio. “Dylan ends his song / ‘You’d see what a drag you are,’ ” wrote Ginsberg. The actual line is “You’d know what a drag it is to see you.” Eventually, as the story goes, Ginsberg would obtain a tape recorder with help from Dylan.

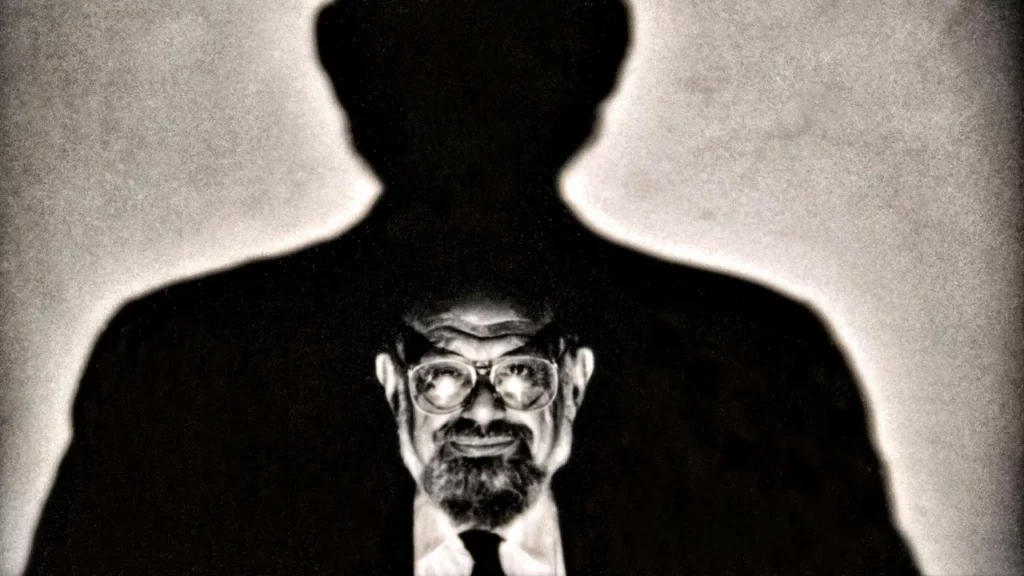

“Beginning of a Poem of These States,” which appears in the first pages of “The Fall of America: Poems of These States 1965-1971,” demonstrates Ginsber’s growing enthusiasm for highly detailed modes of self-recording. “The Fall of America” is Ginsberg’s fifth collection of poems (after “HOWL,” “Kaddish,” “Reality Sandwiches,” and “Planet News”) and his longest and most critically successful standalone work. The original edition, published by City Lights in 1972, is a cult object, a chunky little book with a minimalist black and white cover, title and author intoned in a cool, lightly-serifed font. As the title suggests, its poems convey images of national decline and collapse, which Ginsberg attributes to an interlocking set of causes: racial exploitation and violence; the outsized power of certain depraved politicians and corporate owners; widespread, reality-warping abuses of mass media; and compounding environmental devastations—in short, an evergreen guide to the end of the empire. But virtuosic topicality and overdetermined relevance to our own moment aren’t what make “The Fall of America” special. To understand its prescience, and experience its enduring appeal, you have to zoom in on its process.

“The Fall of America” was famously written with the help of a portable tape machine. When Ginsberg began work on it in 1965, amateur recording was a relatively new possibility: magnetic tape technology had just made its way into the U.S. at the end of the Second World War, when reel-to-reel recorders were machines the size of mini-fridges, generally acquired by record labels or entertainment and news outlets. Rapid advancements ensued, and by the nineteen-sixties there were smaller, battery-powered tape machines available to consumers. Ginsberg used an Uher, an upscale German model that was distributed in the United States by Martel. The Uher was easy to carry (weighing only several pounds), plus its special features included a rechargeable battery that could be plugged into any outlet and a microphone that doubled as an electromagnetic remote control, making it possible to start and stop the recorder from a distance.

“The Fall of America” compresses the hours Ginsberg spent playing with his new toy. When he was composing what he called “auto poesy,” Ginsberg would switch on the machine and spout lines into the air of the Volkswagen. He recorded his reactions to billboards, pop songs, ads, and news reports; confessed intimate feelings; and addressed an eclectic list of higher powers (Hindu saints, yogis, Herman Melville, and Bob Dylan). He would replay the recordings again and again, listening carefully—repeating and re-recording certain lines, refining and building on his rhythms. Then he’d transcribe the tapes’ contents into his journal, editing, formatting, and polishing as he went. His journals suggest that he planned to clear his schedule of commitments, drive back and forth across the continental U.S., and spontaneously record his thoughts about life, friendship, waning youth, and the search for authenticity. Ginsberg himself seems to have acknowledged the conceit as derivative—an aping of “On the Road,” Jack Kerouac’s best-selling novel of the late nineteen-fifties.

“Pray for me, Jackie,” Ginsberg appears to have told his brand-new tape recorder around 1965, addressing it like a telephone receiver in a burst of coy neediness. “All I can do is think like you, write like you.” The comparison flatters Kerouac, who spent the late nineteen-sixties living semi-reclusively and struggling with alcoholism in Florida. But it fairly reflects Ginsberg’s passion for mimesis, and for talking to people who may or may not be listening.

Like Kerouac’s “spontaneous prose,” auto poesy was a more labor- and time-intensive process than the coinage suggests. Ginsberg began taping many of his public appearances, as well as his casual and private conversations. He carried the Uher with him everywhere—into auditoriums, classrooms, restaurants, train stations. He taped himself on planes and at parties. His use accelerated so quickly that it caused fights with his boyfriend, Peter Orlovsky. By 1966, recordings suggest that Peter felt abandoned for the little machine and the hyper-absorbed moods it could induce. “Work your fucking recorder, man,” Peter once told Ginsberg in the middle of a heated argument. Ginsberg tried to mollify him—“I like you, Peter, everything’s all right.”—Peter snubbed him. “You like your publicity,” Peter said, suggesting that the recorder appealed as a surrogate audience. “You keep it.” (This tape now sits in Ginsberg’s enormous tape archive at Stanford University; the tape is labelled “Peter angry in car,” in Ginsberg’s handwriting). Ginsberg would eventually avail himself of Peter’s insult: the long poem “Iron Horse” opens with a detailed transcription of the poet literally getting off to the sound of his own voice; he dirty-talks the microphone while masturbating, fully nude, in a train car.

Ginsberg once wrote in his journal that “the best antipolice state strategy was total exposure of all secrets.” “Unclassify everybody’s private life,” he suggested. “President Johnson’s as well as mine.” The years spanned by “The Fall of America” roughly coincide with the time that the F.B.I. was compiling a dossier on Ginsberg, focussing primarily on his sexuality, drug use, and psychiatric history. We could see Ginsberg’s obsession with self-recording as strategic, an effort to counteract repressive invasions of privacy by preëmptively surrendering everything to the eyes and ears of everyone.