The Peace at Saturnalia (Part 1)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 2 Jan 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

A Bioscopic Foundation of Festivities, Religion, Syncretism, Shamanism, Immorality, Materialism, Gifting and Humanity

“Has the Global Pursuit of Materialism and Debauchery Replaced the Peaceful Spirituality of the Festive Season?”[1]

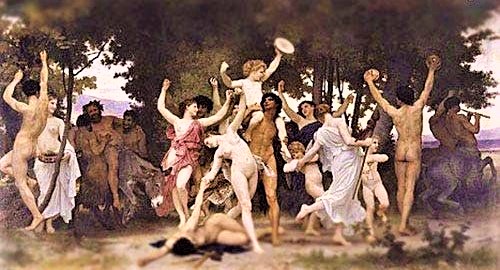

The Joyous Festivities During the Feast of Saturnalia[2]

Seneca complains that the “whole mob has let itself go in pleasures”

(Epistles, XVIII.3).[3]

This paper landscapes the socio-anthropological evolution of the Festive Season, usually associated with the date of 25th December in the Gregorian calendar, in the 21st century, from the time of ancient pagan customs celebrating the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere, observed on 22nd December, characterised by equal day and night, bringing hope to the cold, darkened countries in the upper latitudes, that the days will be progressively getting longer and the nights shorter, based on astronomical knowledge. This generates a feeling of anticipation and looking expectantly to new beginnings, in all of biological types of flora and fauna, including humanoids. The history of this period dates back to antiquity and its basis is deeply entrenched in paganism, mystics and the practice of shamanism, leading to the emergence of one central character, Santa Claus, the benevolent, portulent and happy savior of humankind, the inimitable Santa Claus, as we all have come to know him, from childhood, traditionally dressed in red, representing happiness, goodness, hope and charity, with an aura of giving.

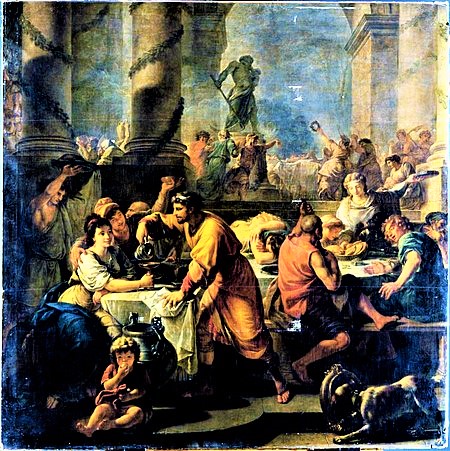

In ancient Rome this period was called Saturnalia, marked by the Feast of Saturnalia, typified by frivolity, immorality, drunken debauchery and paganistic customs, as well as behavioral patterns, which would be shunned upon, in the present day code of conduct, ethics and standards of morality, although these are often violated in office parties, where liquor flows freely and disinhibited behaviour of all humanoid participants, is the norm.

The author has enquired from his friends as to what is “Saturnalia” and as expected, most of them had absolutely no idea of what it is. Some adolescents responded that Saturnalia is the best horror game for Halloween for 2022, while others thought it was the name of one of the 53 moons of the planet Saturn[4], in the galaxy.

In the present era, the equivalent of Saturnalia is the Festive Season, which commences 12 days before Christmas as traditionally celebrated and observed as the date of irth of Jesus Christ in a manger by the majority of Christians, worldwide. This Festive season passes beyond Christmas to include the New Year and holiday associated with it in the Gregorian Calendar. In preparing for this publication, the author spoke to a Christian child of 6 years of age, as to what was Christmas all about and the response was quite surprising. The child responded “It is about Mummy rushing off to the mall to buy things to eat for Christmas, as Daddy likes to eat a lot of food”. Interestingly, the child did not mention Father Christmas, toys, nor going to church, nor gifts. These integral aspects of Christmas are simply forgotten, or of no, or lesser import, to this little child from a middle-income family. Hence, it is apparent that in the 21st century the Saturnalia has become associated with Feast of Food and over indulgence, like the Feast of Saturnalia in ancient Rome, also associated with immorality and promiscuous behavior, causing peace disruption. During Saturnalia, the Romans offered oscillum, effigies of human heads, in place of real human heads.[5],[6]

Let the festivities, begin in ancient, Rome when a festival appropriately called The Feast of Saturnalia was observed during the winter solstice, described by Gaius Valerius Catullus, what he called “the best of days”[7] He was born between 87 and 82 BCE in Verona in Pre-Alpine Gaul. He was a late republican Roman poet, belonging to the neoteric group; their only representative, whose works have survived in greater numbers. Neoterics broke with the Roman tradition of great historical epics. Following the example of Hellenistic poetry, especially Alexandrian poetry, they preferred small-size pieces; epigrams, short scenes, wedding and mourning songs, epillia[8], small epic poem, but chiseled to perfection. It was significant to adopt the principle of constructing poetry on the model of Callimachus. Most often they wrote about personal experiences, especially love. They were characterized by scholarship, mythological, geographical and literary. In mythological epillions, they depicted little-known myths. The poems did not exceed 500 lines.[9] In fact, this period of ongoing festivities in midwinter, were so popular, inspiring and a welcome respite from the darkness of winter, that they were enjoyed on for an entire week.

Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated, beginning with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike.[10] A common custom was the election of a “King of the Saturnalia”, who gave orders to people, which were followed and presided over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria.

Saturnalia was the Roman equivalent to the earlier Greek holiday of Kronia, which was celebrated during the Attic month of Hekatombaion in late midsummer. It held theological importance for some Romans, who saw it as a restoration of the ancient Golden Age, when the world was ruled by Saturn. The Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry interpreted the freedom associated with Saturnalia as symbolizing the “freeing of souls into immortality”. Saturnalia may have influenced some of the customs associated with later celebrations in western Europe occurring in midwinter, particularly traditions associated with Christmas, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, and Epiphany. In particular, the historical western European Christmas custom of electing a “Lord of Misrule” may have its roots in Saturnalia celebrations.

In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labour in a state of innocence. The revelries of Saturnalia were supposed to reflect the conditions of the lost mythical age. The Greek equivalent was the Kronia,[11] which was celebrated on the twelfth day of the month of Hekatombaion, which occurred from around mid-July to mid-August on the Attic calendar. The Greek writer Athenaeus also cites numerous other examples of similar festivals celebrated throughout the Greco-Roman world, including the Cretan festival of Hermaia in honor of Hermes, an unnamed festival from Troezen in honor of Poseidon, the Thessalian festival of Peloria in honor of Zeus Pelorios, and an unnamed festival from Babylon. He also mentions that the custom of masters dining with their slaves was associated with the Athenian festival of Anthesteria and the Spartan festival of Hyacinthia. The Argive festival of Hybristica, though not directly related to the Saturnalia, involved a similar reversal of roles in which women would dress as men and men would dress as women.[12]

The ancient Roman historian Justinus credits Saturn with being a historical king of the pre-Roman inhabitants of Italy:

“The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal.”

— Justinus, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 43.3[13]

Although probably the best-known Roman holiday, Saturnalia as a whole is not described from beginning to end in any single ancient source. Modern understanding of the festival is pieced together from several accounts dealing with various aspects.[14] The Saturnalia was the dramatic setting of the multivolume work of that name by Macrobius, a Latin writer from late antiquity who is the major source for information about the holiday. Macrobius describes the reign of Justinus’ “king Saturn” as “a time of great happiness, both on account of the universal plenty that prevailed and because as yet there was no division into bond and free – as one may gather from the complete license enjoyed by slaves at the Saturnalia.” In Lucian’s Saturnalia it is Chronos himself who proclaims a “festive season, when ’tis lawful to be drunken, and slaves have license to revile their lords”.[15]

In one of the interpretations in Macrobius’s work, Saturnalia is a festival of light leading to the winter solstice, with the abundant presence of candles symbolizing the quest for knowledge and truth.[16] The renewal of light and the coming of the new year was celebrated in the later Roman Empire at the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the “Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun”, on 25 December.[17]

The popularity of Saturnalia continued into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, and as the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, many of its customs were recast into or at least influenced the seasonal celebrations surrounding Christmas and the New Year.[18]

In the Jewish tradition, Avodah Zarah [19] is “foreign worship”, meaning “idolatry” or “strange service”) is the name of a tractate of the Talmud, located in Nezikin, the fourth Order of the Talmud dealing with damages, lists Saturnalia as a “festival of the gentiles,” along with the Kalents of January and Kratesis. Avodah Zarah records that Ḥanan Rava said, “Kalends begins eight days after the winter solstice and Saturnura begins eight days before the winter solstice”. Ḥananel Ḥushiel, followed by Rashi, claims: “Eight days before the solstice, their festival was for all eight days,” which slightly overstates the Saturnalia’s historical six-day length, possibly to associate the holiday with Hanukkah, in Judaism.

In the Jerusalem Talmud, Avodah Zarah claims the etymology of Saturnalia is שנאה טמונה śinʾâ ṭǝmûnâ “hidden hatred,” and refers to the hatred Esau, whom the Rabbis believed had fathered Rome, harbored for Jacob.[20]

The Babylonian Talmud’s Avodah Zarah ascribes the origins of Saturnalia (and Kalends) to Adam, who saw that the days were getting shorter and thought it was punishment for his sin:

When the First Man saw that the day was continuously shortening, he said, “Woe is me! Because I have sinned, the world darkens around me, and returns to formless and void. This is the death to which Heaven has sentenced me!” He decided to spend eight days in fasting and prayer. When he saw the winter solstice, and he saw that the day was continuously lengthening, he said, “It is the order of the world!” He went and feasted for eight days. The following year, he feasted for both. He established them in Heaven’s name, but they established them in the name of idolatry.[21]

In the Babylonian Avodah Zarah, this etiology is attributed to the tannaim, but the story is suspiciously similar to the etiology of Kalends attributed by the Jerusalem Avodah Zarah to Abba Arikha.[22]

Unlike several Roman religious festivals which were particular to cult sites in the city, the prolonged seasonal celebration of Saturnalia at home could be held anywhere in the Empire. [23] Saturnalia continued as a secular celebration long after it was removed from the official calendar. [24] As William Warde Fowler notes: “[Saturnalia] has left its traces and found its parallels in great numbers of medieval and modern customs, occurring about the time of the winter solstice.”[25]

The actual date of Jesus’s birth is unknown.[26] A spurious correspondence between Cyril of Jerusalem and Pope Julius I (337–352), quoted by John of Nikiu in the 9th century, is sometimes given as a source for a claim that, in the fourth century AD, Pope Julius I formalized that the nativity of Christ should be celebrated on 25 December.[27] Some speculate that this is around the same time as the Saturnalia celebrations and that part of the reason why he chose this date may have been because he was trying to create a Christian alternative to Saturnalia.[28] Another reason for the decision may have been because, in 274 AD, the Roman emperor Aurelian had declared 25th December the birthdate of Sol Invictus and Julius I may have thought that he could attract more converts to Christianity by allowing them to continue to celebrate on the same day. He may have also been influenced by the idea that Jesus had died on the anniversary of his conception; because Jesus died during Passover and, in the third century AD, Passover was celebrated on 25th March,[29] he may have assumed that Jesus’s birthday must have come nine months later, on 25th December. But in fact the correspondence is spurious.[30]

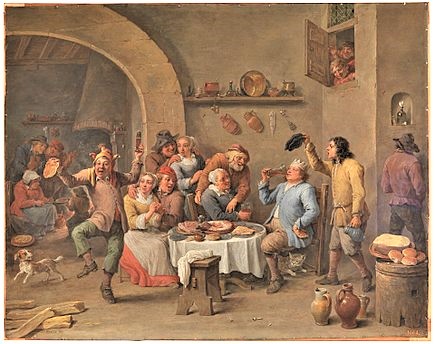

The King Drinks (between 1634 and 1640) by David Teniers the Younger, showing a Twelfth Night celebration with a “Lord of Misrule”[31]

As a result of the close proximity of dates, many Christians in western Europe continued to celebrate traditional Saturnalia customs in association with Christmas and the surrounding holidays.[32] Like Saturnalia, Christmas during the Middle Ages was a time of ruckus, drinking, gambling, and overeating. The tradition of the Saturnalicius princeps was particularly influential. In medieval France and Switzerland, a boy would be elected “bishop for a day” on 28 December (the Feast of the Holy Innocents) and would issue decrees much like the Saturnalicius princeps. The boy bishop’s tenure ended during the evening vespers. This custom was common across western Europe, but varied considerably by region; in some places, the boy bishop’s orders could become quite rowdy and unrestrained, but, in others, his power was only ceremonial.[33] In some parts of France, during the boy bishop’s tenure, the actual clergy would wear masks or dress in women’s clothing, a reversal of roles in line with the traditional character of Saturnalia.

During the late medieval period and early Renaissance, many towns in England elected a “Lord of Misrule” at Christmas time to preside over the Feast of Fools.[34] This custom was sometimes associated with the Twelfth Night or Epiphany.[35] A common tradition in western Europe was to drop a bean, coin, or other small token into a cake or pudding; whoever found the object would become the “King (or Queen) of the Bean”. During the Protestant Reformation, reformers sought to revise or even completely abolish such practices, which they regarded as “popish”; these efforts were largely successful. The Puritans banned the “Lord of Misrule” in England[36] and the custom was largely forgotten shortly thereafter, though the bean in the pudding survived as a tradition of a small gift to the one finding a single almond hidden in the traditional Christmas porridge in Scandinavia.[37]

Nonetheless, in the middle of the nineteenth century, some of the old ceremonies, such as gift-giving, were revived in English-speaking countries as part of a widespread “Christmas revival”[38]. During this revival, authors such as Charles Dickens sought to reform the “conscience of Christmas” and turn the formerly riotous holiday into a family-friendly occasion. Vestiges of the Saturnalia festivities may still be preserved in some of the traditions now associated with Christmas.[39] The custom of gift-giving at Christmas time resembles the Roman tradition of giving sigillaria and the lighting of Advent candles resembles the Roman tradition of lighting torches and wax tapers.[40] Likewise, Saturnalia and Christmas both share associations with eating, drinking, gambling, singing, and dancing.[41]

Ruins of the Temple of Saturn (eight columns on right) in Rome, traditionally said to have been constructed in 497 BC[42]

Inset: 2nd-century AD Roman bas-relief depicting the god Saturn, in whose honor the Saturnalia was celebrated, holding a scythe.[43]

The Bottom Line is The Saturnalia reflects the contradictory nature of the deity Saturn himself: “There are joyful and utopian aspects of careless well-being side by side with disquieting elements of threat and danger.”[44] The phrase “io Saturnalia” was the characteristic shout or sautation of the festival, originally commencing after the public banquet on the single day of 17th December.[45] The interjection io (Greek ἰώ, ǐō) is pronounced either with two syllables (a short i and a long o) or as a single syllable (with the i becoming the Latin consonantal j and pronounced yō). It was a strongly emotive ritual exclamation or invocation, used for instance in announcing triumph or celebrating Bacchus, but also to punctuate a joke.[46] As a deity of agricultural bounty, Saturn embodied prosperity and wealth in general. The name of his consort Ops meant “wealth, resources”. Her festival, Opalia, was celebrated on 19th December. The Temple of Saturn housed the state treasury (aerarium Saturni) and was the administrative headquarters of the quaestors, the public officials whose duties included oversight of the mint. It was among the oldest cult sites in Rome, and had been the location of “a very ancient” altar (ara) even before the building of the first temple in 497 BC.[47]

The Romans regarded Saturn as the original and autochthonous ruler of the Capitolium[48] and the first king of Latium or even the whole of Italy.[49] At the same time, there was a tradition that Saturn had been an immigrant deity, received by Janus after he was usurped by his son Jupiter (Zeus) and expelled from Greece.[50] His contradiction, a foreigner with one of Rome’s oldest sanctuaries, and a god of liberation who is kept in fetters most of the year, indicate Saturn’s capacity for obliterating social distinctions.[51] Roman mythology of the Golden Age of Saturn’s reign differed from the Greek tradition. He arrived in Italy “dethroned and fugitive”,[52] but brought agriculture and civilization and became a king. As the Augustan poet Virgil described it:

“He gathered together the unruly race [of fauns and nymphs] scattered over mountain heights, and gave them laws … . Under his reign were the golden ages men tell of: in such perfect peace he ruled the nations.”[53]

The third century Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry took an allegorical view of the Saturnalia. He saw the festival’s theme of liberation and dissolution as representing the “freeing of souls into immortality”, an interpretation that Mithraists may also have followed, since they included many slaves and freedmen.[54] According to Porphyry, the Saturnalia occurred near the winter solstice because the sun enters Capricorn, the astrological house of Saturn, at that time.[55] In the Saturnalia of Macrobius, the proximity of the Saturnalia to the winter solstice leads to an exposition of solar monotheism, the belief that the Sun, Sol Invictus, ultimately encompasses all divinities, as one.[56]It is therefore interesting to note that the different religions have demonstrated syncretism in many aspects of tradition and culture in the present era.

The author takes this opportunity to wish all the readers, collectively the “best of days” during this modern day Saturnalia, in general and a Merry Christmas, in particular to the colleagues, observing the doctrines of the Christian faith, in its different denominations, as applicable.

Saturnalia the 1783 painting by Antoine-François Callet, showing his interpretation of what the Saturnalia might have looked like. The raucous, public festivities, designated as an official event in the classical Roman Religion, characterised by indulgence in food, wine, gambling, gifting and role reversal. These festivities extended from 17th to 23rd December, in the Julian calendar, with observances of public, animal sacrifice and banquet for the god Saturn, with universal Phoenix wearing of the pileus.

References:

[1] Personal quote by the author, December 2022.

[2] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=9e88cdc37f854e10JmltdHM9MTY3MTY2NzIwMCZpZ3VpZD0wYjAyZjg1ZC1mZTdmLTZkY2YtMDU4ZS1lYTIzZmYwZDZjNzYmaW5zaWQ9NTE1Ng&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=0b02f85d-fe7f-6dcf-058e-ea23ff0d6c76&psq=Seneca+complains+that+the+%e2%80%9cwhole+mob+has+let+itself+go+in+pleasures%e2%80%9d+(Epistles%2c+XVIII.3).+&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9jbGFzc2ljYWx3aXNkb20uY29tL2N1bHR1cmUvdHJhZGl0aW9ucy9zYXR1cm5hbGlhLXBhcnR5LWRvbnQtc3RvcC8&ntb=1

[3] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=b6cc01b65051d994JmltdHM9MTY3MTY2NzIwMCZpZ3VpZD0wYjAyZjg1ZC1mZTdmLTZkY2YtMDU4ZS1lYTIzZmYwZDZjNzYmaW5zaWQ9NTIxNw&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=0b02f85d-fe7f-6dcf-058e-ea23ff0d6c76&psq=Seneca+complains+that+the+%e2%80%9cwhole+mob+has+let+itself+go+in+pleasures%e2%80%9d+(Epistles%2c+XVIII.3).+&u=a1aHR0cDovL3d3dy5zdG9pY3MuY29tL3NlbmVjYV9lcGlzdGxlc19ib29rXzEuaHRtbA&ntb=1

[4] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=4c132fe7b8f364dfJmltdHM9MTY3MTc1MzYwMCZpZ3VpZD0wYjAyZjg1ZC1mZTdmLTZkY2YtMDU4ZS1lYTIzZmYwZDZjNzYmaW5zaWQ9NTQ0MA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=0b02f85d-fe7f-6dcf-058e-ea23ff0d6c76&psq=planet+saturn+has+how+many+moons&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9zcGFjZXBsYWNlLm5hc2EuZ292L2hvdy1tYW55LW1vb25zL2VuLyM6fjp0ZXh0PVRoZSUyMG1vc3QlMjB3ZWxsLWtub3duJTIwb2YlMjBKdXBpdGVyJTI3cyUyMG1vb25zJTIwYXJlJTIwSW8sU2F0dXJuJTIwaGFzJTIwNTMlMjBtb29ucyUyMHRoYXQlMjBoYXZlJTIwYmVlbiUyMG5hbWVkLg&ntb=1

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Taylor%2C%20Rabun%20(2005).%20%22Roman%20Oscilla%3A%20An%20Assessment%22.%20RES%3A%20Anthropology%20and%20Aesthetics.%20Chicago%2C%20Illinois%3A%20The%20University%20of%20Chicago%20Press.%2048%20(48)%3A%20101.%20doi%3A10.1086/RESv48n1ms20167679.%20JSTOR%C2%A020167679.%20S2CID%C2%A0193568609.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Mueller%202010%2C%20p.%C2%A0222%3B%20Versnel%2C%20however%2C%20proposes%20that%20Lua%20Saturni%20should%20not%20be%20identified%20with%20Lua%20Mater%2C%20but%20rather%20refers%20to%20%22loosening%22%3A%20she%20represents%20the%20liberating%20function%20of%20Saturn%20Versnel%201992%2C%20p.%C2%A0144

[7] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=b902ccbf70baec24JmltdHM9MTY3MTY2NzIwMCZpZ3VpZD0wYjAyZjg1ZC1mZTdmLTZkY2YtMDU4ZS1lYTIzZmYwZDZjNzYmaW5zaWQ9NTE5NQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=0b02f85d-fe7f-6dcf-058e-ea23ff0d6c76&psq=Gaius+Valerius+Catullus%2c&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQ2F0dWxsdXM&ntb=1

[8] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=343003d9dfe58125JmltdHM9MTY3MTY2NzIwMCZpZ3VpZD0wYjAyZjg1ZC1mZTdmLTZkY2YtMDU4ZS1lYTIzZmYwZDZjNzYmaW5zaWQ9NTIxNA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=0b02f85d-fe7f-6dcf-058e-ea23ff0d6c76&psq=small+epic+poem&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9sZWFybm9kby1uZXd0b25pYy5jb20vZmFtb3VzLWVwaWMtcG9lbXM&ntb=1

[9] https://imperiumromanum.pl/en/biographies/gaius-valerius-catullus/

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Miller%2C%20John%20F.%20%22Roman%20Festivals%2C%22%20in%20The%20Oxford%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Ancient%20Greece%20and%20Rome%20(Oxford%20University%20Press%2C%202010)%2C%20p.%20172.

[11] https://books.google.com/books?id=ezDlXl7gP9oC

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Parker%2C%20Robert%20(2011).%20On%20Greek%20Religion.%20Ithaca%2C%20New%20York%3A%20Cornell%20University%20Press.%20p.%C2%A0211.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D8014%2D7735%2D5.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Smith%2C%20Andrew.%20%22Justinus%3A%20Epitome%20of%20Pompeius%20Trogus%20(7)%22.%20www.attalus.org.%20Retrieved%202017%2D09%2D07.

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Dolansky%202011%2C%20p.%C2%A0484.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Roth%2C%20Marty.%20Drunk%20the%20Night%20Before%3A%20An%20Anatomy%20of%20Intoxication.%20University%20of%20Minnesota%20Press.

[16] Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.1.8–9; Jane Chance, Medieval Mythography: From Roman North Africa to the School of Chartres, A.D. 433–1177 (University Press of Florida, 1994), p. 71.

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Robert%20A.%20Kaster%2C%20Macrobius%3A%20Saturnalia%2C%20Books%201%E2%80%932%20(Loeb%20Classical%20Library%2C%202011)%2C%20note%20on%20p.%2016.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=%22The%20reciprocal%20influences%20of%20the%20Saturnalia%2C%20Germanic%20solstitial%20festivals%2C%20Christmas%2C%20and%20Chanukkah%20are%20familiar%2C%22%20notes%20C.%20Bennet%20Pascal%2C%20%22October%20Horse%2C%22%20Harvard%20Studies%20in%20Classical%20Philology%2085%20(1981)%2C%20p.%20289.

[19] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=e0c5fc60c97b1f39JmltdHM9MTY3MTc1MzYwMCZpZ3VpZD0wYjAyZjg1ZC1mZTdmLTZkY2YtMDU4ZS1lYTIzZmYwZDZjNzYmaW5zaWQ9NTQxOQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=0b02f85d-fe7f-6dcf-058e-ea23ff0d6c76&psq=avodah+zarah+meaning&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQXZvZGFoX1phcmFoIzp-OnRleHQ9QXZvZGFoJTIwWmFyYWglMjAlMjhIZWJyZXclM0ElMjAlRDclQTIlRDclOTElRDclOTUlRDclOTMlRDclOTQlMjAlRDclOTYlRDclQTglRDclOTQlMjAlRTIlODAlOEUlMkMlMjBvciUyMCUyMmZvcmVpZ24sZm91cnRoJTIwT3JkZXIlMjBvZiUyMHRoZSUyMFRhbG11ZCUyMGRlYWxpbmclMjB3aXRoJTIwZGFtYWdlcy4&ntb=1

[20] https://web.archive.org/web/20210820143819/https://www.sefaria.org/Jerusalem_Talmud_Avodah_Zarah.3a.1

[21] https://www.sefaria.org/Avodah_Zarah.8a.7

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Sarit%2C%20Kattan%20Gribetz%20(2020%2D11%2D17).%20Time%20and%20Difference%20in%20Rabbinic%20Judaism.%20doi%3A10.23943/princeton/9780691192857.001.0001.%20ISBN%C2%A09780691192857.%20S2CID%C2%A0241016818.

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Woolf%2C%20Greg%2C%20%22Found,celebrating%20the%20Saturnalia.

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Michele%20Renee%20Salzman%2C%20%22Religious%20Koine%20and%20Religious%20Dissent%2C%22%20in%20A%20Companion%20to%20Roman%20Religion%20(Blackwell%2C%202007)%2C%20p.%20121.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Fowler%2C%20Roman%20Festivals%2C%20p.%20268.

[26] Struthers, Jane (2012). The Book of Christmas: Everything We Once Knew and Loved about Christmastime. London, England: Ebury Press. pp. 17–21. ISBN 9780091947293.

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Letter%20of%20Cyril,1844.%20p.%C2%A0965.

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=John%2C%20J.%20(2005).%20A%20Christmas%20Compendium.%20New%20York%20City%2C%20New%20York%20and%20London%2C%20England%3A%20Continuum.%20p.%C2%A0112.%20ISBN%C2%A00%2D8264%2D8749%2D1.

[29] https://books.google.com/books?id=YKaJsdIkOgsC&q=Saturnalia+Christmas&pg=PA18

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Martindale%2C%20Cyril%20(1908).%20%22Christmas%22.%20The%20Catholic%20Encyclopedia.%20New%20York%3A%20Robert%20Appleton%20Company.%20Retrieved%202018%2D11%2D18.

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:David_Teniers_(II)_-_Twelfth-night_(The_King_Drinks)_-_WGA22083.jpg

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=John%2C%20J.%20(2005).%20A%20Christmas%20Compendium.%20New%20York%20City%2C%20New%20York%20and%20London%2C%20England%3A%20Continuum.%20p.%C2%A0112.%20ISBN%C2%A00%2D8264%2D8749%2D1.

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Mackenzie%2C%20Neil%20(2012).%20The%20Medieval%20Boy%20Bishops.%20Leicestershire%2C%20England%3A%20Matadore.%20pp.%C2%A026%E2%80%9329.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1780880%2D082.

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Forbes%2C%20Bruce%20David%20(2007).%20Christmas%3A%20A%20Candid%20History.%20Berkeley%2C%20California%3A%20University%20of%20California%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A09%E2%80%9310.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D520%2D25104%2D5.

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Shaheen%2C%20Naseeb%20(1999).%20Biblical%20References%20in%20Shakespeare%27s%20Plays.%20Newark%2C%20Maryland%3A%20University%20of%20Delaware%20Press.%20p.%C2%A0196.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D61149%2D358%2D0.

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISBN_(identifier)

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Sjue%2C%20K.%20(25%20December%202016).%20%22Historien%20om%20mandelen%20i%20gr%C3%B8ten%22.%20Dagbladet.%20Retrieved%2025%20November%202019.

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Rowell%2C%20Geoffrey%20(December%201993).%20%22Dickens%20and%20the%20Construction%20of%20Christmas%22.%20History%20Today.%2043%20(12).%20Retrieved%20December%2028%2C%202016.

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Stuttard%2C%20David%20(17%20December%202012).%20%22Did%20the%20Romans%20invent%20Christmas%3F%22.%20bbc.co.uk.%20British%20Broadcasting%20Company.

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Forbes%2C%20Bruce%20David%20(2007).%20Christmas%3A%20A%20Candid%20History.%20Berkeley%2C%20California%3A%20University%20of%20California%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A09%E2%80%9310.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D520%2D25104%2D5.

[41] Stuttard, David (17 December 2012). “Did the Romans invent Christmas?”. bbc.co.uk. British Broadcasting Company.

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Mueller%202010%2C%20p.%C2%A0221.

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:0_Autel_d%C3%A9di%C3%A9_au_dieu_Malakb%C3%AAl_et_aux_dieux_de_Palmyra_-_Musei_Capitolini_(1b).JPG

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Versnel%201992%2C%20p.%C2%A0148.

[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Versnel%201992%2C%20p.%C2%A0141.

[46] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Entry%20on%20io%2C%20Oxford%20Latin%20Dictionary%20(Oxford%3A%20Clarendon%20Press%2C%201982%2C%201985%20reprinting)%2C%20p.%20963.

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Fowler%2C%20Roman%20Festivals%2C%20p.%20271.

[48] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=The%20Capitolium%20had%20thus%20been%20called%20the%20Mons%20Saturnius%20in%20older%20times.

[49] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#CITEREFVersnel1992

[50] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#CITEREFVersnel1992

[51] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Versnel%201992%2C%20pp.%C2%A0139%2C%20142%E2%80%93143.

[52] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#cite_ref-John_109-3:~:text=Versnel%2C%20%22Saturnus%20and%20the%20Saturnalia%2C%22%20p.%20143.

[53] Virgil, Aeneid 8. 320–325, as cited by Versnel 1992, p. 143

[54] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Porphyry%2C%20De%20antro%2023%2C%20following%20Numenius%2C%20as%20cited%20by%20Roger%20Beck%2C%20%22Qui%20Mortalitatis%20Causa%20Convenerunt%3A%20The%20Meeting%20of%20the%20Virunum%20Mithraists%20on%20June%2026%2C%20A.D.%20184%2C%22%20Phoenix%2052%20(1998)%2C%20p.%20340.%20One%20of%20the%20speakers%20in%20Macrobius%27s%20Saturnalia%20is%20Vettius%20Agorius%20Praetextatus%2C%20a%20Mithraist.

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=Beck%2C%20Roger%2C%20%22Ritual%2C%20Myth%2C%20Doctrine%2C%20and%20Initiation%20in%20the%20Mysteries%20of%20Mithras%3A%20New%20Evidence%20from%20a%20Cult%20Vessel%2C%22%20Journal%20of%20Roman%20Studies%2090%20(2000)%2C%20p.%20179.

[56] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnalia#:~:text=van%20den%20Broek%2C%20Roel%2C%20%22The%20Sarapis%20Oracle%20in%20Macrobius%20Sat.%2C%20I%2C%2020%2C%2016%E2%80%9317%2C%22%20in%20Hommages%20%C3%A0%20Maarten%20J.%20Vermaseren%20(Brill%2C%201978)%2C%20vol.%201%2C%20p.%20123ff.

______________________________________________

READ PART 2: Peace at Gregorian Christmas: The Evolution of Christmas in the 21st Century

READ PART 3: Palpable Peace: The Institution of the Iconic Christmas Tree

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Italy, Religion, Roman empire, Saturnalia

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 2 Jan 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Peace at Saturnalia (Part 1), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.