International Criminal Court Advancing Global Injustice, Unaccountability and Criminal Agenda against Guardians of Peace

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 19 Jun 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

Parental guidance is recommended for minors.

“Rise, O’ all you intelligent, righteous humanoids”. Just as the war in Ukraine has become a festering sore in the politically motivated, combined, western, proxy war against Russia, the plight of Palestinians is a chronic human rights violation, festering, as an ulcer, already systemic in its manifestations, generated by Israel in its ongoing philosophy of ethnic cleansing. In reality it is a genocide, which is obfuscated by various institutes and governments for their personal support of the Zionist agenda.[1]

Picture Top: Israeli attacks destroy 1530 Gaza homes. A Palestinian man, without shoes, mourns the death of his family and demolition of his modest flat, in Gaza. Israeli commander was reportedly recorded giving order to bomb a clinic in Gaza. Thousands flee homes in Gaza after Israel warns them that staying will ‘endanger’ lives, as part of Ethnic Cleansing.

Picture Bottom: The funeral for al-Swerki was held soon after his death on May 3, 2023, from injuries suffered in the Israeli bombing while he was sleeping at home.

Photo credit: Abdelhakim Abu Riash/Al Jazeera Media Network

The Nova Kakhovka Dam[2], in Ukraine[3], near the city, of war-torn Kherson[4], was destroyed in the early hours of 6 June 2023,[5],[6],[7] causing extensive flooding along the lower Dnieper river (also known as Dinipro River[8]). The Kakhovka Dam was already damaged days before it collapsed on Tuesday, per the BBC and CNN. Satellite photos published by the BBC show that part of a roadway went missing between Thursday and Friday. It’s unclear who inflicted the damage to the roadway, or if it affected the eventual breach.[9]

However, what is important to note that The International Criminal Court [10](ICC) has launched an investigation into the destruction of the Kakhovka dam, as the crisis leaves 700,000 people with limited access to drinking water and causes billions in damage, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy [11]said on 11th June 2023. Representatives from the ICC visited the Kherson region where 46 settlements remain flooded, the Kyiv Independent reported. Water levels are dropping, down from 5.5 metres to 4 metres over the weekend, but the evacuation process is ongoing as houses, ecosystems and businesses have all been destroyed. 2,718 have been evacuated from Kherson Oblast and 982 from Mykolaiv Oblast[12], as of 11th June 2023. Kyiv, which accuses Russia of deliberately blowing up the Kakhovka dam, says it is cooperating with the ICC, providing full access to the impacted areas, witnesses and evidence. The EU has backed Ukraine’s accusations that Russia is behind the attack. “This investigation is very important for the security of the whole world,” Zelenskyy said.

Already damages amount to UAH55bn ($1.5bn) but could rise to $10bn over the next five years as agricultural losses are expected to be massive, according to Ruslan Strilets, Minister of Environmental Protection, Ukraine Business News reported. Irrigation systems across southern Ukraine are without a water source and won’t be restored for at least three to seven years, threatening 1-1.5mn hectares of farmland and the region’s agricultural sector. The hardest hit region is Kherson, with 94% of its irrigation systems without a water source, followed by 74% in Zaporizhzhia and 30% in Dnipropetrovsk. Fields could turn into deserts as early as next year, warned the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food.

An image taken on 05th June 2023, before the dam was breached, shows damage to the roadway. Yet, interestingly, the matter has warranted expedited ICC investigation, which is being fast-tracked. Photo credit: Maxar Technologies[13]/Handout via Reuters

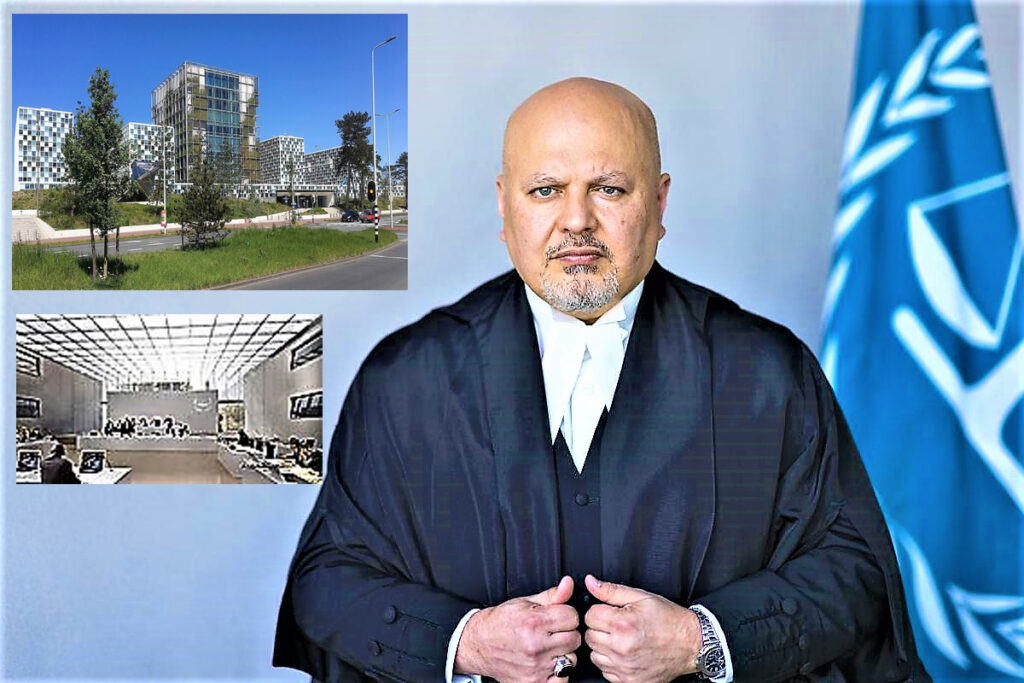

This paper discusses the International Criminal Court’s formation, background history current status and how it is selectively involved in certain issues, while some blatant crimes against humanity are not registered as yet, in spite of calls and appeals for the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC to investigate the case. It is also interesting to note that daily calls are made by AL Jazeera Media Network, as observed in their English service news channel, transmitting over a protracted period of time, or simply, conveniently ignored. Yet the Kakhovka Dam, an inanimate entity, was fast tracked with respect to the processing of the case, resulting in ICC investigators were in Kherson, after, merely, five days later, beginning their investigations. In contrast, the case of the targeted assassination of the American, Palestinian journalist, Shireen Abu Akleh, on 11th May 2021, is not filed as yet. It is also an appalling indictment of the world body for justice and accountability that only on the morning of Saturday, 17th June 2023 it was reported on Al Jazeera News that the ICC Chief Prosecutor, Karim Khan QC [14] INTENDS to visit Palestine[15], later this year, after repeated and daily appeals by Al Jazeera Network for the ICC to investigate the targeted assassination of Shireen Abu Akleh[16]. Israel, with the greatest impunity categorically states that “none of its soldiers will be made to answer questions in relation to the killing of the journalist, Shireen Abu Akleh”[17]. Since the start of 2023, Israeli forces have killed at least 156 Palestinians, including 26 children. The death toll includes 36 Palestinians killed by the Israeli army during a four-day assault on the besieged Gaza Strip between May 9 and 13th 2023[18], as reported on 23rd May 2023. Since then the fatalities have increased with no word from the UN Humanitarian Chief [19]nor from the UN Security Council, on the ongoing killings of the civilians in Palestine. Since then, Israeli occupation soldiers shot and killed three Palestinians during a large-scale assault on Balata refugee camp in the northern West Bank city of Nablus early this Monday, morning, 22nd May 2023 and injured six others, one of them seriously. They also demolished a house during the raid.[20] The aforementioned brutal atrocities, committed, with a disproportionate use of force and shoot to kill order to the Israel Defence Forces “wolf pack” are clearly indicative of crimes against civilians, including children, yet ICC has not taken any steps against these transgressions by Israel.

It is therefore necessary to review the mandate and the historical reasons for the formation of the ICC. The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal that was established to prosecute individuals accused of committing serious international crimes. The ICC was created through the adoption of the Rome Statute on July 17, 1998, and it officially came into force on July 1, 2002. Its headquarters are located in The Hague, Netherlands. The inaugural meeting of the International Criminal Court (ICC) took place in Rome, Italy. The meeting, known as the Rome Conference, was held from June 15 to July 17, 1998. During this conference, the Rome Statute was adopted, which established the ICC as a permanent international criminal court. The treaty entered into force on July 1, 2002, after it was ratified by 60 countries. The decision to establish the headquarters of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands was based on several factors:

- Historical Significance: The Hague has a long history of hosting international judicial institutions and has been a centre for international law and justice. It is home to institutions like the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The choice of The Hague as the seat of the ICC builds upon this tradition and expertise in international law.

- Access to Expertise: The Netherlands has a strong legal infrastructure and a well-developed legal system. The Hague offers access to legal professionals, experts, and support services necessary for the effective functioning of the ICC.

- Diplomatic Support: The Netherlands has been a strong supporter of the ICC and played a crucial role in the negotiations leading to the establishment of the Court. Hosting the ICC in The Hague strengthens the cooperation between the Court and the Dutch government.

Regarding the establishment of global branches or offices in “hot areas,” the ICC does not have formal branches or regional offices in specific locations. However, the ICC operates globally and can conduct investigations and trials in different countries based on its jurisdiction. The Court collaborates with national authorities and international organizations to carry out its work effectively. The ICC’s focus is on addressing serious international crimes regardless of the geographical location, and it can initiate investigations and prosecutions wherever the crimes have taken place, subject to the jurisdictional limitations defined by the Rome Statute and the cooperation of relevant states.

The ICC was established as a response to the need for a permanent international tribunal to address the most heinous crimes that threaten the peace, security, and well-being of the international community. It serves as a court of last resort, intervening only when national courts are unwilling or unable to prosecute the perpetrators of these crimes.

The ICC has jurisdiction over four core international crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. Genocide refers to acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. Crimes against humanity encompass widespread or systematic attacks directed against any civilian population, including murder, torture, rape, forced disappearance, and persecution. War crimes are violations of the laws or customs of war, such as targeting civilians, using child soldiers, or intentionally destroying civilian infrastructure. The crime of aggression involves the planning, preparation, initiation, or execution of acts of aggression by a state against the territorial integrity or political independence of another state.

The ICC’s jurisdiction extends to crimes committed on the territory of states parties to the Rome Statute, as well as crimes committed by nationals of states parties. Additionally, the ICC can also exercise jurisdiction when a non-state party accepts the court’s jurisdiction or when a situation is referred to the court by the United Nations[21] Security Council.

The ICC operates through a two-tier structure consisting of the Office of the Prosecutor and the judicial divisions. The Office of the Prosecutor investigates and prosecutes cases, while the judicial divisions consist of the Pre-Trial Chamber, Trial Chamber, and Appeals Chamber. The Pre-Trial Chamber determines whether there is sufficient evidence to proceed with a trial, the Trial Chamber hears the cases and delivers judgments, and the Appeals Chamber hears appeals from both the prosecution and the defence.

The ICC’s work is guided by the principles of complementarity and subsidiarity. Complementarity means that the ICC can only intervene when national courts are unable or unwilling to prosecute, ensuring that states retain primary responsibility for bringing perpetrators to justice. Subsidiarity refers to the ICC’s role as a court of last resort, intervening only when states are unable or unwilling to genuinely investigate and prosecute.

Since its inception, the ICC has opened investigations and prosecuted individuals for crimes committed in various regions of the world. Some notable cases include those related to the situation in Darfur, Sudan; the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Uganda; the Central African Republic; and Libya. The ICC has also issued arrest warrants for high-profile individuals, including former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. Todate, no such warrant of arrest was issued for Israelis leader Netanhayu who has been in office for extended terms and returned in January 2023 to continue with his crimes against humanity, with greater impunity.

The ICC has faced several challenges and criticisms throughout its existence. Some argue that the court’s jurisdiction is limited and that it has focused primarily on cases from Africa, leading to allegations of bias. Others claim that the ICC’s effectiveness is hindered by its lack of enforcement mechanisms, as it relies on state cooperation for arrests and the execution of its judgments. Furthermore, the United States, China, Russia, and a few other countries have not ratified the Rome Statute, limiting the court’s global reach and impact.

Despite these challenges, the ICC continues to play a crucial role in the global fight against impunity for the most serious international crimes. It serves as a deterrent to potential perpetrators, promotes accountability, and provides justice to victims. The court’s ongoing work and evolving jurisprudence contribute to the development of international criminal law and the establishment of a more just and peaceful world.

It is necessary to understand that there is another world, legal body called the International Court of Justice (IJC), The International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) are two distinct institutions with different mandates and functions.

The ICC, as described, is an international tribunal established to prosecute individuals accused of committing serious international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. It is a permanent court and operates as a separate entity from the United Nations, although it maintains cooperative relationships with the UN and its member states. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. It is often referred to as the “World Court” and is located in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, just like the ICC. The ICJ has a broader jurisdiction, as it deals with legal disputes between states rather than individual criminal responsibility. The ICJ is responsible for resolving disputes of a legal nature submitted to it by states through contentious cases. It can provide advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized United Nations organs and specialized agencies. The ICJ’s jurisdiction is based on the consent of the states involved, and its decisions are binding on the parties involved in a particular case.

Essentially, while both the ICC and the ICJ are international courts based in The Hague, they have distinct roles and functions. The ICC focuses on prosecuting individuals for serious international crimes, while the ICJ adjudicates legal disputes between states and provides advisory opinions on legal matters. To amplify this broad division of the respective mandates, The International Criminal Court (ICC) would have jurisdiction over cases related to genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. If there were allegations of genocide, for example, the ICC could potentially investigate and prosecute individuals accused of committing such crimes.

On the other hand, disputes over the use of water from the Grand Renaissance Dam would fall under the purview of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The ICJ is responsible for resolving legal disputes between states, including disputes related to water resources. If there were a legal disagreement between countries concerning the utilization or management of the dam’s water, the involved states could potentially bring the dispute to the ICJ for resolution.

It’s important to note that the specific circumstances and details of each case or dispute would determine whether it falls within the jurisdiction of the ICC or the ICJ. Each court has its own criteria and legal framework for determining jurisdiction and deciding which cases or disputes they can address.

The early history of the International Criminal Court (ICC) can be traced back to the mid-20th century when discussions about the need for a permanent international criminal tribunal began. The horrors of World War II and the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials that followed highlighted the need for a permanent institution to prosecute individuals responsible for the most serious international crimes. Efforts to establish an international criminal court gained momentum in the 1990s. In 1994, the International Law Commission (ILC) presented a draft statute for an international criminal court. This draft became the basis for further negotiations and discussions among states.

The Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC, was adopted on July 17, 1998, during a diplomatic conference held in Rome, Italy. It was the result of years of negotiations and consultations among states, international organizations, and civil society groups. The Rome Statute was open for signature and ratification by states, and it needed 60 ratifications to enter into force. The motivation for the formation of the ICC was to address the need for a permanent international institution that could prosecute individuals responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. The ICC was intended to serve as a court of last resort, intervening only when national courts were unable or unwilling to prosecute these crimes. Its establishment aimed to contribute to the prevention of such crimes, deterrence, and accountability. The financing of the ICC comes from several sources. The primary source of funding is contributions made by states parties to the Rome Statute. Each state party contributes to the budget of the court based on an assessment scale determined by the Assembly of States Parties, the ICC’s governing body composed of representatives from the states that have ratified or acceded to the Rome Statute. States that are not parties to the Rome Statute can also contribute voluntarily.

The Rome Statute[22] is a pivotal international treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC) as a permanent and independent judicial institution. Here is a summary of its key aspects:

- Purpose: The Rome Statute’s primary objective is to end impunity for the most serious crimes that deeply affect the international community as a whole. It aims to hold individuals accountable for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and, as of 2010, the crime of aggression.

- Jurisdiction: The ICC has jurisdiction over the crimes mentioned above if they are committed on the territory of a state party to the Statute or by nationals of a state party. The Court can also exercise jurisdiction if the United Nations Security Council refers a situation to it, regardless of the state’s membership status.

- Structure: The Rome Statute establishes the organs of the ICC, including the Assembly of States Parties, the Presidency, the Judicial Divisions (Pre-Trial, Trial, and Appeals Chambers), and the Office of the Prosecutor. These entities work together to ensure the effective functioning of the Court.

- Investigation and Prosecution: The Office of the Prosecutor conducts investigations into alleged crimes falling within the Court’s jurisdiction. The Court’s proceedings are guided by the principle of complementarity, which means that the ICC steps in only when national jurisdictions are unable or unwilling to genuinely investigate and prosecute these crimes.

- Fair Trial Rights: The Rome Statute enshrines the rights of the accused, including the presumption of innocence, the right to a fair and public trial, the right to counsel, and the right to confront witnesses. It places a strong emphasis on ensuring due process and protecting the rights of suspects and defendants.

- Victims’ Participation and Reparations: The Statute recognizes the rights of victims to participate in ICC proceedings and to seek reparations for harm suffered. Victims can present their views and concerns, and the Court may award reparations to individual victims or communities affected by the crimes.

- Cooperation: The Rome Statute obliges states to cooperate fully with the ICC, including the arrest and surrender of suspects, providing access to evidence and witnesses, and enforcing sentences. States Parties are expected to implement the necessary legislative and practical measures to ensure effective cooperation.

The Dutch government’s involvement with the ICC is significant due to the location of the court’s headquarters in The Hague, Netherlands. The Dutch government provides support and infrastructure for the functioning of the ICC, including the provision of premises and facilities. The Netherlands, being the host country, has certain obligations and responsibilities under the host state agreement with the ICC. The choice of The Hague as the seat of the ICC was based on several factors. The Netherlands has a long-standing tradition of hosting international institutions and tribunals, and The Hague is known as the international city of peace and justice. The city already housed other international courts, such as the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, making it a natural choice for the ICC’s establishment. The Hague’s infrastructure, legal expertise, and respect for the rule of law were also significant factors in selecting the city as the ICC’s headquarters. The presence of international embassies, legal professionals, and academic institutions in The Hague further contributed to its suitability as a hub for international criminal justice.

In summary, the ICC’s early history stems from discussions and efforts to establish a permanent international criminal court in the aftermath of World War II. The ICC was motivated by the need to prosecute individuals responsible for serious international crimes. It is primarily funded by contributions from states parties, and the Dutch government’s involvement relates to its provision of support and infrastructure as the host country. The establishment of the ICC in The Hague was influenced by the city’s existing international legal institutions, infrastructure, and commitment to the rule of law.

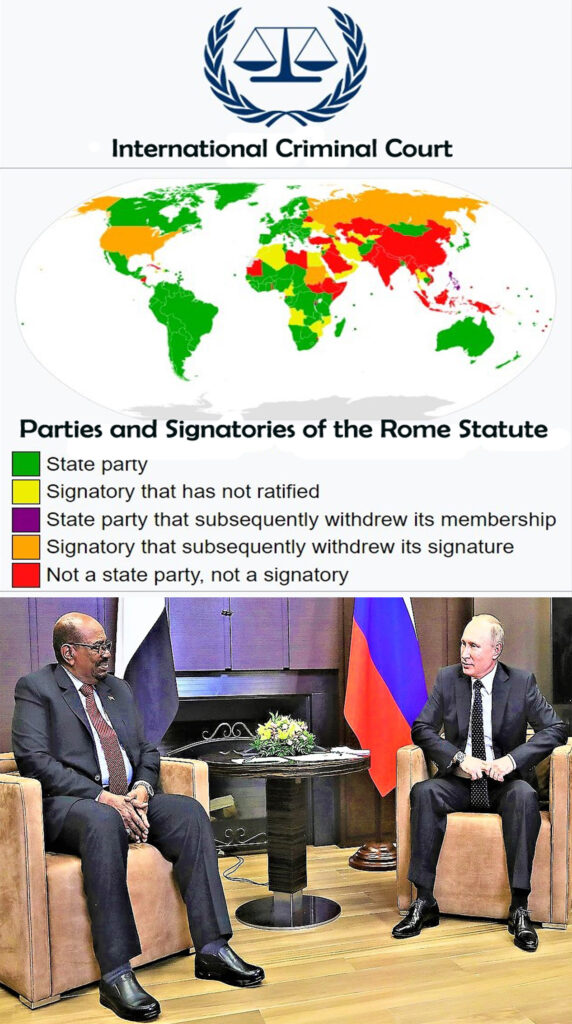

Top Photo: The International Criminal Court, The Hague, Netherlands showing the countries which are signatories to the Rome Statute

Bottom Photo: Left, President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir of The Republic of Sudan, indicted by ICC on 14 July 2008 and President Vladimir Putin of Russia warrant issued on 17 March 2023. Both Presidents were issued with warrants of arrest by ICC, related to crimes against humanity and associated with non-compliance of South Africa of the ICC warrants.

The important cases that were brought before the International Criminal Court (ICC) and have been successfully prosecuted since its inception:

- The Prosecutor v. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo[23] (Democratic Republic of the Congo): Thomas Lubanga, a Congolese warlord and leader of the Union of Congolese Patriots, was the first person to be convicted by the ICC. He was found guilty of recruiting and using child soldiers in the Ituri region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lubanga was sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2012.

- The Prosecutor v. Germain Katanga and Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui (Democratic Republic of the Congo):[24] Germain Katanga and Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui were Congolese militia leaders involved in the attack on the village of Bogoro in Ituri in 2003. They were charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes, including murder, rape, sexual slavery, and using child soldiers. Katanga was convicted in 2014, while Ngudjolo was acquitted in 2012.

- The Prosecutor v. Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo (Central African Republic)[25]: Jean-Pierre Bemba, a Congolese politician and former vice-president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes committed by his militia, the Movement for the Liberation of Congo, in the Central African Republic. He was found guilty in 2016 for crimes including murder, rape, and pillaging. Bemba was sentenced to 18 years in prison, but the conviction was later overturned on appeal in 2018.

- The Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi (Mali): Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi,[26] an Islamic extremist, was charged with the war crime of intentionally directing attacks against religious and historic buildings in Timbuktu, Mali, in 2012. He pleaded guilty and became the first person to be convicted solely for the destruction of cultural heritage. Al Mahdi was sentenced to 9 years in prison in 2016.

- The Prosecutor v. Dominic Ongwen (Uganda): Dominic Ongwen,[27] a senior commander in the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), was charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in northern Uganda. Ongwen faced charges of murder, enslavement, and sexual slavery, among others. In 2021, he was found guilty and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

The notable cases from other, different regions, that were brought before national or international courts rather than specifically the International Criminal Court (ICC):

South America:

- Operation Condor[28]: This was a coordinated campaign of state-sponsored terrorism and human rights abuses conducted by South American military dictatorships in the 1970s and 1980s. Several cases related to human rights violations during this period have been brought before courts in various countries, including Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay.

- Fujimori Trial (Peru[29]): Alberto Fujimori, the former President of Peru, was tried and convicted in 2009 for human rights abuses and corruption during his presidency in the 1990s. He was found guilty of authorizing killings, kidnappings, and other human rights violations committed by security forces.

Europe:

- International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY):[30] The ICTY was established to prosecute individuals responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide committed during the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. Notable cases include those against Slobodan Milošević, Radovan Karadžić, and Ratko Mladić.

- International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR[31]): The ICTR was established to prosecute individuals responsible for the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Cases include those against Jean-Paul Akayesu and Théoneste Bagosora.

Far East:

- Khmer Rouge Trials (Cambodia)[32]: The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) were established to prosecute senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime responsible for crimes committed during the 1970s. Notable cases include those against Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan.

South Africa:

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission[33] (TRC): The TRC was a unique process that aimed to provide a forum for victims and perpetrators of apartheid-era human rights abuses to tell their stories and seek amnesty. While it was not a court in the traditional sense, it played a significant role in promoting reconciliation and accountability in South Africa. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in South Africa was not directly affiliated with the International Criminal Court (ICC). The TRC was a domestic initiative established in South Africa to address the human rights violations and crimes committed during the apartheid era. It operated independently from the ICC and had a specific mandate and process of its own.

UK:

- Bloody Sunday Inquiry: The Bloody Sunday Inquiry, also known as the Saville Inquiry,[34] was established to investigate the events of January 30, 1972, when British soldiers opened fire on civil rights demonstrators in Northern Ireland. The inquiry concluded in 2010, and its findings led to a formal apology from the British government. This was guided by ICC

USA:

- Nuremberg Trials:[35] While not specific to the USA, the Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals held after World War II to prosecute prominent Nazi leaders and others involved in war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. The trials were conducted by an international tribunal in Nuremberg, Germany and formed the basis of ICC legislature.

- Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp[36]: The detention and treatment of individuals at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp have raised legal and human rights concerns. Various legal challenges have been brought before courts in the USA regarding the indefinite detention and treatment of detainees.

There are 123 states that have become signatories to the Rome Statute[37] of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and 72 countries who are not, including USA, UK, Israel[38] and India out of a total of 295 countries, globally.

The decision of a country to become a member of the International Criminal Court (ICC), or not is influenced by various factors. In the case of the United States, a democratic country, there are several reasons why it has not ratified the Rome Statute and joined the ICC:

- Concerns about Sovereignty: Some countries, including the United States, have expressed concerns about the potential impact of ICC jurisdiction on their national sovereignty. They believe that the ICC’s authority could potentially infringe on their domestic legal systems and limit their ability to independently address and adjudicate crimes committed by their citizens.

- Bilateral Immunity Agreements: The United States has actively pursued bilateral immunity agreements, commonly known as Article 98 agreements, with other countries. These agreements seek to provide immunity for US personnel from ICC prosecution. The US has signed such agreements with several countries, effectively shielding its citizens from the ICC’s jurisdiction.

- Security Council Veto Power: The Rome Statute grants the United Nations Security Council the authority to refer cases to the ICC. As a permanent member of the Security Council with veto power, the United States has concerns about the potential for politically motivated prosecutions and the possibility of its own citizens being targeted based on political considerations.

- Domestic Legal Framework: The United States has a robust domestic legal system and institutions to address and prosecute international crimes. It relies on its own courts, including federal courts, to prosecute individuals for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide committed by US citizens or on US territory.

The ICC rulings in cases are binding on the countries involved. When the ICC issues a judgment in a case, it is legally binding on the states parties to the Rome Statute, which includes the country against which the judgment was issued. The judgments of the ICC are final and not subject to appeal within the Court. Once the ICC renders a judgment, it is the responsibility of the concerned state to ensure compliance with the Court’s decisions. This can include actions such as executing arrest warrants, providing support for the transfer of convicted individuals to the ICC’s custody, and implementing sentences imposed by the Court. However, it is important to note that the ICC relies on the cooperation of states to enforce its judgments. In some cases, states may face challenges or may choose not to fully cooperate with the ICC. This can complicate the process of implementing ICC judgments and can require further diplomatic efforts and international pressure to ensure compliance. The ICC does not have its own enforcement mechanisms, such as a dedicated police force, and relies on the cooperation of states and the international community to enforce its judgments and decisions.

If a state ignores an ICC judgment or fails to comply with its obligations, it can have various implications:

- Diplomatic Pressure: Other states and international actors can exert diplomatic pressure on the non-compliant state to encourage it to abide by the ICC judgment. This can involve diplomatic interventions, public statements, or diplomatic sanctions to encourage compliance.

- Referral to the United Nations: The ICC can refer the matter to the United Nations (UN) Security Council, particularly if the non-compliance poses a threat to international peace and security. The Security Council, as a UN body, has the authority to take measures, including imposing sanctions or other enforcement actions, to address the situation.

- Sanctions and Consequences: States or regional organizations may impose targeted sanctions or other measures against the non-compliant state. These can include travel bans, asset freezes, or restrictions on trade or financial transactions. The aim is to create economic or political pressure to encourage compliance.

- International Isolation: Non-compliance with an ICC judgment can lead to international isolation for the state involved. Other countries may choose to limit diplomatic relations, cooperation, or engagement with the non-compliant state in various areas, such as trade, development assistance, or cultural exchanges.

- Prosecution in Other Jurisdictions: If the non-compliant state fails to hold individuals accountable for crimes under ICC jurisdiction, other countries may choose to exercise universal jurisdiction and prosecute those individuals in their own national courts. This can be done based on the principle that certain crimes, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, are offenses of concern to the international community as a whole.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) can issue a judgment against individuals from countries that are not signatories to the Rome Statute. The ICC’s jurisdiction extends beyond its member states under certain circumstances. There are two main ways in which the ICC can exercise jurisdiction over individuals from non-member states:

- Referral by the United Nations Security Council: The Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, has the power to refer situations to the ICC, even if the country involved is not a member. In such cases, the ICC can exercise jurisdiction over individuals who are alleged to have committed crimes within the referred situation. This allows the ICC to investigate and prosecute individuals for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, even in non-member states.

- Voluntary Acceptance of Jurisdiction: Non-member states can voluntarily accept the jurisdiction of the ICC by submitting a declaration to the Court. This declaration can be a one-time acceptance for a specific situation or a broader acceptance of the ICC’s jurisdiction. Once accepted, the ICC can exercise jurisdiction over individuals from that state for crimes committed within the accepted scope.

While the ICC[39] can issue judgments against individuals from non-member states under these circumstances, the practical implementation and enforcement of such judgments may face challenges. The ICC relies on the cooperation of states to arrest and surrender individuals, and non-compliant states can pose obstacles to the execution of ICC judgments. Additionally, it is important to distinguish between the jurisdiction of the ICC and the jurisdiction of national courts. Even if a country is not a signatory to the Rome Statute or subject to ICC jurisdiction, national courts can exercise jurisdiction over international crimes committed within their territories under the principle of universal jurisdiction or through bilateral or multilateral agreements.

The Nuremberg Trials [40]made significant contributions to the development of international criminal law and laid the foundation for the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the future. In fact these trials were the precursor for the legal framework of ICC. They introduced the concept of individual criminal responsibility for international crimes and rejected the idea of immunity for high-ranking officials. The trials affirmed the principle that individuals can be held accountable for their actions, even if they were acting under the orders of a government or military authority.

Furthermore, the trials established important legal precedents, such as the recognition of crimes against humanity as a distinct category of offenses and the codification of the principles of superior responsibility and command responsibility. These principles hold individuals responsible for crimes committed by subordinates under their control or in their areas of authority. The Nuremberg Trials also had a profound impact on the memory and collective consciousness of the world. They brought attention to the horrors of the Holocaust and the extent of Nazi atrocities, making it difficult for the world to turn a blind eye to such crimes in the future. The trials served as a symbol of justice and a reminder of the importance of accountability in the face of gross human rights violations.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is governed by its founding document, known as the Rome Statute. Here is a summary of the key aspects of the ICC’s constitution:

- Purpose: The ICC was established to prosecute individuals for the most serious crimes of international concern, including genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. Its ultimate goal is to contribute to the prevention of such crimes and ensure justice for victims.

- Jurisdiction: The ICC has jurisdiction over individuals who commit crimes within the territory of states party to the Rome Statute or by nationals of states party to the statute. It can also exercise jurisdiction when a situation is referred to it by the United Nations Security Council or by a state that is not a party to the statute.

- Structure: The ICC consists of four main organs: the Presidency, the Judicial Division, the Office of the Prosecutor, and the Registry. The Presidency is responsible for the overall administration of the court, while the Judicial Division is responsible for the trial and appellate chambers. The Office of the Prosecutor investigates and prosecutes cases, and the Registry supports the court’s operations.

- Judges: The ICC has a panel of 18 judges who are elected by the Assembly of States Parties. They serve nine-year terms and are responsible for conducting trials, making legal determinations, and ensuring the fair and impartial administration of justice.

- Prosecutor: The Prosecutor is an independent official appointed by the Assembly of States Parties. The Prosecutor investigates and prosecutes cases before the court, based on the principle of complementarity, which means that the court intervenes only when national legal systems are unwilling or unable to prosecute.

- Cooperation: States party to the Rome Statute are obligated to cooperate with the ICC in various ways, including the arrest and surrender of suspects, providing evidence and witnesses, and enforcing sentences. Non-party states can also choose to cooperate with the court on a voluntary basis.

- Rights of the Accused and Victims: The Rome Statute emphasizes the rights of the accused, including the presumption of innocence, the right to a fair trial, and the right to legal representation. It also recognizes the rights of victims to participate in the proceedings, to receive reparations, and to have their views and concerns taken into account.

- Relationship with National Jurisdictions: The ICC is intended to complement national legal systems. It encourages states to investigate and prosecute international crimes themselves and provides support and assistance to national authorities in building their capacity to handle such cases.

The Rome Statute has been ratified by a significant number of countries, reflecting a global commitment to ending impunity for the most serious international crimes. However, it is important to note that not all countries are party to the Rome Statute, and therefore, the ICC’s jurisdiction is not universal.

The mandate of the International Criminal Court (ICC) is outlined in the Rome Statute, which established the court. The mandate is primarily focused on the prosecution of individuals responsible for the most serious crimes of international concern, namely genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. The ICC’s mandate is not fixed and can be subject to change through amendments to the Rome Statute.

The Rome Statute itself can be amended by a two-thirds majority vote of the states parties to the statute. This means that the member states have the power to modify the court’s mandate by introducing new crimes or expanding the jurisdiction of the ICC. However, any amendments must be consistent with the principles and purposes of the statute.

Since its formation, the ICC’s mandate has already undergone some changes. For example, the crime of aggression was added to the ICC’s jurisdiction through an amendment that was adopted in 2010 but only came into effect in 2018. This expansion allowed the ICC to investigate and prosecute individuals for the crime of aggression, which refers to the planning, preparation, initiation, or execution of acts of aggression by a state against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of another state.

Additionally, there have been ongoing discussions and debates within the Assembly of States Parties, the governing body of the ICC, regarding potential amendments or clarifications to certain provisions of the Rome Statute. These discussions have covered topics such as the definition of the crime of aggression, the scope of the court’s jurisdiction, and the relationship between the ICC and other international bodies.

It is important to note that any changes to the ICC’s mandate require a significant level of consensus among the states parties, as well as careful consideration of legal, political, and practical implications. Any proposed amendments must respect the principles of justice, fairness, and the overall goals of the court in ensuring accountability for the most serious international crimes.

Therefore, while the ICC’s mandate can be subject to modification, any changes would be made through a rigorous process involving the states parties and would require broad support within the international community.

Since certain countries like USA, Israel and India who are not co signatories to the Rome Statute and there not members of ICC, can be prosecuted by other mechanisms to address alleged crimes committed by these countries:

- National Jurisdiction: Countries have the primary responsibility to investigate and prosecute crimes committed within their territories. If there is evidence of crimes against humanity, genocide, or war crimes, affected individuals, organizations, or even other states can pursue legal action within the domestic legal systems of those countries. This can involve filing criminal complaints, supporting investigations, or advocating for the initiation of legal proceedings.

- Universal Jurisdiction: Some countries have laws that allow them to exercise jurisdiction over certain international crimes, regardless of where they were committed or the nationality of the perpetrators or victims. Universal jurisdiction enables national courts to investigate and prosecute individuals suspected of crimes such as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, even if the crimes were committed outside their own territories. This mechanism can provide an avenue for accountability when the alleged perpetrators are present in a country that exercises universal jurisdiction.

- Ad hoc International Tribunals: In specific cases, ad hoc international tribunals may be established to address crimes committed during particular conflicts or events. Examples include the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). These tribunals are created by the United Nations Security Council and have jurisdiction over crimes committed within specific time frames and geographic areas.

- Hybrid Courts: Hybrid courts are international or internationalized courts that combine elements of national and international law and involve a mix of international and national judges, prosecutors, and staff. These courts are typically established through agreements between the country in question and the international community. Hybrid courts can address crimes committed in specific countries or regions and may provide an alternative avenue for accountability when national systems face challenges or are unable to effectively address the crimes.

- Civil Litigation: In some cases, victims or their representatives may seek justice through civil litigation in national courts. Civil lawsuits can be brought against individuals or entities, including state actors, alleging human rights abuses or other violations. Such cases can help to establish accountability, seek reparations for victims, and contribute to the development of legal precedent.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has a hierarchical structure and leadership positions. At the top of the hierarchy is the Presidency, which consists of three individuals: the President and two Vice-Presidents. The Presidency is responsible for the overall management and strategic direction of the court.

The President of the ICC is elected by the judges from among their own ranks and serves a term of three years. The President represents the court externally, presides over judicial sessions, and performs other functions as outlined in the Rome Statute and the ICC’s Rules of Procedure and Evidence. Below the Presidency, there are several key positions within the ICC:

- Office of the Prosecutor (OTP): The OTP is responsible for conducting investigations and prosecutions of crimes within the jurisdiction of the court. The Prosecutor is the head of the OTP and is elected by the Assembly of States Parties for a term of nine years.

- Chambers: The Chambers are responsible for the judicial functions of the court. There are three divisions: the Pre-Trial Division, the Trial Division, and the Appeals Division. Each division is headed by a Presiding Judge who oversees the work of the chamber and ensures the efficient administration of justice.

- Registrar: The Registrar is responsible for the non-judicial aspects of the court’s operations. This includes managing the court’s budget, administration, and support services. The Registrar is appointed by the judges for a term of five years.

- In addition to these key positions, the ICC has various other departments and offices that support its work, such as the Office of Public Counsel for Victims, the Office of the Public Counsel for the Defence, and the Office of the Prosecutor’s Investigation Division.

While the ICC operates under a hierarchical structure, it is important to note that decisions and actions are made collectively and based on the principles of independence, impartiality, and judicial integrity. The court operates under the authority of the Rome Statute and is governed by its provisions, as well as other relevant legal instruments and regulations.

The process of lodging a case at the International Criminal Court (ICC) involves several stages. The simplified overview of the process is:

- Jurisdiction: The ICC has jurisdiction over four core crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. To initiate a case, the alleged crimes must fall within the ICC’s jurisdiction, and the country where the crimes occurred must either be a state party to the Rome Statute or have accepted the jurisdiction of the ICC through a declaration or referral.

- Communication: Anyone can submit information about alleged crimes to the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP). This can be done through various means, such as submitting a written communication or using the online submission form available on the ICC’s website.

- Preliminary Examination: The OTP conducts a preliminary examination to assess the information and determine whether there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation. During this stage, the OTP evaluates factors such as the seriousness of the alleged crimes, the jurisdiction of the court, the admissibility of the case, and the interests of justice.

- Investigation: If the OTP determines that there is a reasonable basis to proceed, it can request authorization from the Pre-Trial Chamber to open an investigation. The Pre-Trial Chamber reviews the request and decides whether to grant authorization based on legal criteria. If authorization is granted, the OTP initiates an investigation, which involves gathering evidence, interviewing witnesses, and collecting relevant information.

- Confirmation of Charges: After completing the investigation, the OTP may submit a request to the Pre-Trial Chamber to issue a warrant of arrest or a summons to appear. The Pre-Trial Chamber reviews the evidence and determines whether there are sufficient grounds to proceed with a trial. If the charges are confirmed, the case proceeds to the trial stage.

- Trial: The trial takes place before the Trial Chamber, composed of judges. The accused is afforded the right to a fair and impartial trial, including the presumption of innocence and the opportunity to present a defence. The Trial Chamber examines the evidence, hears testimonies, and makes determinations of guilt or innocence.

- Appeal: If the accused is convicted, both the prosecution and the defence have the right to appeal the decision to the Appeals Chamber. The Appeals Chamber reviews the legal and factual aspects of the case and determines whether errors were made that affected the outcome. It can affirm, reverse, or modify the trial judgment.

- Enforcement: If the accused is found guilty, the ICC does not have its own enforcement mechanism. It relies on cooperation from member states to execute arrest warrants, transfer suspects, and enforce sentences. Member states are obligated to cooperate with the ICC in accordance with their legal obligations.

Cases can be lodged with the International Criminal Court (ICC) by various entities, including individuals, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and countries. The ICC allows individuals and NGOs to submit information or complaints related to alleged crimes falling within its jurisdiction. This mechanism is known as “communications.”

Any individual or organization can submit a communication to the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) to bring attention to alleged crimes. The communication should provide relevant information and evidence supporting the allegations, as well as identify the alleged perpetrators and victims. The OTP evaluates the communication during the preliminary examination stage to determine whether there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation. However, it is important to note that while individuals and NGOs can initiate the process by submitting a communication, the decision to proceed with an investigation and subsequent prosecution ultimately rests with the OTP and the ICC judges. The OTP conducts its own assessment of the information provided, considering factors such as the seriousness of the alleged crimes, jurisdiction, admissibility, and the interests of justice. Additionally, countries themselves can refer situations or specific cases to the ICC. This can be done voluntarily by a country that is a state party to the Rome Statute, or by a country that is not a state party but accepts the jurisdiction of the ICC through a declaration or a referral. In some cases, the United Nations Security Council can also refer situations to the ICC. The ICC’s jurisdiction is complementary to national jurisdictions. This means that the court steps in only when national authorities are unable or unwilling to genuinely investigate and prosecute the alleged crimes. The ICC encourages cooperation with national authorities and may work in partnership with them to address accountability for international crimes. Overall, while cases can be lodged by individuals, NGOs, and countries, the ICC’s discretion in initiating investigations and prosecutions ensures that the court maintains its independence and applies consistent legal standards in its pursuit of justice.

Upon conviction, the ICC’s Trial Chamber or Appeals Chamber may issue a judgment specifying the sentence, which can include imprisonment or fines. The judgment also outlines the obligations of the member states regarding the enforcement of the sentence. These obligations typically include arresting and transferring the convicted individual to a state willing to enforce the sentence, providing the necessary facilities for imprisonment, and supervising the execution of the sentence.

The ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) and the Registry, which oversees the administration of the court, work closely with member states to facilitate the enforcement process. The OTP may seek assistance from member states in executing arrest warrants, facilitating the transfer of the convicted person, or providing logistical support for the enforcement of the sentence.

The actual enforcement of the sentence depends on the cooperation of member states, and it is subject to national laws and procedures. Member states have the discretion to decide how they will carry out the enforcement, including the specific prison facility or location where the convicted person will serve their sentence. The ICC encourages member states to cooperate fully and promptly in the enforcement process to ensure the effective administration of justice. However, not all member states have the capacity or willingness to enforce ICC sentences. In such cases, the ICC relies on other member states that are willing and able to carry out the enforcement. The court continues to engage with member states to promote cooperation and encourage the execution of its sentences to uphold the principles of accountability and justice. The enforcement of ICC sentences relies on the cooperation and commitment of member states to fulfil their obligations under the Rome Statute and their respective domestic laws.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) does not have the authority to impose the death penalty. The ICC’s Statute, which serves as its governing document, explicitly states that the maximum penalty it can impose is imprisonment. The Rome Statute, which established the ICC, reflects a global trend away from the use of the death penalty. Many countries, including those that are party to the Rome Statute, have abolished or placed a moratorium on the death penalty. As a result, the ICC’s jurisdiction is limited to imposing terms of imprisonment as the maximum penalty for individuals found guilty of crimes within its jurisdiction. The ICC’s focus is on achieving justice, ensuring accountability, and promoting the rule of law through fair and impartial trials. It aims to provide due process and fair treatment to all individuals appearing before the court, including the accused. The absence of the death penalty in the ICC’s sentencing regime aligns with the evolving norms and standards regarding punishment for international crimes.

The perception that more African countries and individuals have faced prosecution at the International Criminal Court (ICC) has been a subject of debate and criticism. While it is true that a significant number of cases before the ICC have involved situations in Africa, it is important to consider several factors that have contributed to this perception:

- Referrals and Self-Referrals: The ICC’s jurisdiction is triggered by different mechanisms, including referrals by states and self-referrals by countries themselves. Some African countries, such as Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Mali, and Sudan, have voluntarily referred situations within their territories to the ICC for investigation and prosecution. This has resulted in a concentration of cases from Africa.

- Lack of National Capacity: In some situations, African countries have struggled to effectively investigate and prosecute serious crimes within their jurisdictions due to factors such as armed conflict, political instability, weak institutions, or limited resources. As a result, they may seek the assistance of the ICC to address the accountability gap.

- International Support: The involvement of the ICC in African cases is also influenced by international support and pressure. The international community, including regional organizations and advocacy groups, has called for accountability in cases of alleged crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. This can result in increased attention and engagement by the ICC in situations in Africa.

- Ongoing Conflicts: Several conflicts and crises in Africa have given rise to situations that fall within the ICC’s jurisdiction. These include conflicts in countries like Sudan, Libya, and the Central African Republic, where widespread and grave human rights abuses have occurred, necessitating international intervention.

The case involving Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir and his visit to South Africa in 2015 is indeed an important example that raised questions about compliance with the International Criminal Court (ICC). Omar Al-Bashir had been indicted by the ICC for alleged crimes committed in the Darfur region of Sudan, including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. During his visit to South Africa in June 2015, the ICC had issued arrest warrants for Omar Al-Bashir. As a state party to the Rome Statute, South Africa was obligated to cooperate with the ICC and arrest him. However, South African authorities allowed Omar Al-Bashir to leave the country despite the pending arrest warrants, which drew criticism from the international community and raised concerns about non-compliance. The matter was subsequently brought before the South African courts. The Pretoria High Court, in its ruling, held that the South African government’s failure to arrest Omar Al-Bashir was a violation of its legal obligations under domestic law and international treaty obligations. The court declared that the South African government had failed to comply with its obligations as a state party to the Rome Statute. The South African government appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Appeal, arguing that as a head of state, Omar Al-Bashir enjoyed immunity from arrest under customary international law. However, in December 2016, the Supreme Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal, reaffirming the earlier decision that the South African government had a duty to arrest Omar Al-Bashir. The incident in South Africa and the failure to arrest Omar Al-Bashir raised concerns about the enforcement of ICC arrest warrants and the cooperation of states with the court. It highlighted challenges faced by the ICC in ensuring the arrest and surrender of individuals wanted for international crimes.

It is important to note that the ICC does not have its own police force or enforcement mechanism. It relies on the cooperation of states to execute arrest warrants and surrender individuals to the court. When a state fails to comply with its obligations, the ICC may report the matter to the United Nations Security Council, which has the power to take action to address non-compliance. In the case of Omar Al-Bashir, the matter was brought before the Security Council, but no formal action was taken. The incident involving Omar Al-Bashir’s visit to South Africa highlighted the ongoing challenges and complexities associated with the enforcement of ICC arrest warrants and the need for states to uphold their obligations under the Rome Statute. It also underscored the importance of international cooperation and the role of the Security Council in addressing non-compliance with ICC arrest warrants.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) does not have formal institutional relationships or liaison privileges with specific law enforcement agencies such as Interpol, MI6, Mossad, NSS, or the FBI. The ICC is an independent judicial institution and operates separately from national law enforcement agencies. However, the ICC does engage in cooperation and coordination with various entities, including law enforcement agencies, on a case-by-case basis. The ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) may seek assistance from national authorities, including law enforcement agencies, in the execution of its mandate, such as obtaining evidence, conducting investigations, and making arrests. When the ICC issues arrest warrants or requests assistance, it relies on the cooperation of individual states and their respective law enforcement agencies to carry out the necessary actions. National authorities, including the agencies mentioned, may respond to specific requests from the ICC for assistance, considering their own legal frameworks and priorities. Cooperation between the ICC and national law enforcement agencies occurs within the framework of international law and relevant bilateral or multilateral agreements. The nature and extent of such cooperation depend on the specific circumstances of each case and the willingness of states to aid the ICC.

Human trafficking falls within the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) under certain circumstances. The ICC has jurisdiction over four core international crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. While human trafficking itself is not explicitly listed as one of these crimes, aspects of human trafficking can intersect with the ICC’s jurisdiction.

Crimes against humanity, as defined in the Rome Statute that established the ICC, include a range of acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population. These acts can include enslavement, imprisonment, sexual slavery, forced labour, and other forms of severe deprivation of physical liberty.

If the acts of human trafficking meet the criteria of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population and are committed as part of a broader context of crimes against humanity, then the ICC may have jurisdiction over the situation. This would typically involve cases where human trafficking is perpetrated on a large scale and as part of a broader campaign of criminal acts against a population.

Crimes of aggression refer to the use of armed force by a state against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of another state, in violation of the United Nations Charter. The crime of aggression was included as one of the core international crimes under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Rome Statute. According to the Rome Statute, a person can be held criminally responsible for the crime of aggression if they participate in the planning, preparation, initiation, or execution of an act of aggression. It applies to both state and non-state actors, including political or military leaders, who are involved in the decision-making process leading to an act of aggression. The crime of aggression is distinct from acts of self-defence or actions authorized by the United Nations Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. It requires that the use of force by a state be without justification and in violation of the fundamental principles of international law. It is important to note that the ICC’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression is subject to certain conditions. The ICC may exercise jurisdiction over the crime of aggression only if it has been ratified by the state involved or if the Security Council refers the matter to the ICC. Additionally, the ICC’s exercise of jurisdiction over the crime of aggression was activated on July 17, 2018, with a provision that allows the jurisdiction to be applied retroactively to acts committed after 01st July 2002, and that meet the definition of aggression. Since the crime of aggression is a complex and politically sensitive crime, the implementation and interpretation of its provisions require the agreement and cooperation of states. The ICC’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression reflects the international community’s efforts to deter and hold accountable those responsible for acts that constitute aggression and undermine global peace and security.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) faces several challenges that impact its effectiveness and ability to fulfill its mandate. Here are some of the main challenges:

- Limited Jurisdiction: The ICC’s jurisdiction is based on the principle of complementarity, which means it can only investigate and prosecute crimes when states are unable or unwilling to do so. This limitation often hinders the ICC’s ability to address crimes committed by powerful states or within states that are not party to the Rome Statute.

- Political Interference: The ICC operates in a highly politicized environment, and political interests of states can interfere with its work. Some states may exert pressure or influence to prevent investigations or prosecutions of individuals from their own countries or their allies. This challenge undermines the impartiality and independence of the court.

- Lack of Universal Participation: Not all countries are signatories to the Rome Statute, limiting the ICC’s jurisdictional reach. Major powers like the United States, China, and Russia are not ICC members, which restricts the court’s ability to hold accountable individuals from these countries.

- Enforcement of Arrest Warrants: The ICC relies on states’ cooperation in executing arrest warrants and apprehending individuals. Lack of cooperation or non-compliance by states can hinder the arrest and surrender of suspects, as seen in cases like Omar Al-Bashir.

- Resource Constraints: The ICC operates with limited resources, which can affect its ability to efficiently investigate and prosecute cases. Insufficient funding and staffing can lead to delays in proceedings and impact the court’s overall effectiveness.

- Security Risks: Conducting investigations and prosecutions related to war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity can involve significant security risks. ICC staff, witnesses, and victims may face threats, intimidation, and attacks, making it challenging to carry out their work effectively.

- Limited Deterrence: The ICC’s impact on deterrence is a subject of debate. Critics argue that the court’s inability to swiftly apprehend and prosecute individuals, especially those in positions of power, diminishes its deterrent effect.

- Perceptions of Bias: The ICC has faced criticism for allegedly being biased in its selection of cases and focus on African countries. Some perceive the court as targeting African states disproportionately, which has strained the relationship between the ICC and African nations.

Addressing these challenges requires continued efforts to strengthen the ICC’s independence, expand its jurisdiction, enhance cooperation with states, secure sufficient resources, and ensure the safety and protection of those involved in its proceedings. It also requires engaging with non-member states to encourage their participation and support for international justice mechanisms.

While the International Criminal Court (ICC) has had successful prosecutions, there have been instances where cases have faced challenges or failed due to insufficient evidence. Here are a few high-profile cases where ICC prosecutions encountered difficulties related to evidence:

- Case against Uhuru Kenyatta: The ICC brought charges against Uhuru Kenyatta, the current President of Kenya, for his alleged role in the post-election violence in 2007-2008. However, the case against Kenyatta collapsed due to the ICC’s inability to obtain sufficient evidence and witness cooperation. Charges were dropped in 2014.

- Case against Jean-Pierre Bemba: Jean-Pierre Bemba, a former vice president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, faced charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity for the actions of his troops in the Central African Republic. The ICC initially convicted Bemba in 2016, but the conviction was later overturned on appeal due to errors in the trial chamber’s assessment of his control over the troops.

- Case against Laurent Gbagbo: Laurent Gbagbo, the former president of Ivory Coast, faced charges of crimes against humanity for his alleged role in post-election violence in 2010-2011. However, the ICC acquitted Gbagbo in 2019, citing the prosecution’s failure to prove his criminal responsibility beyond a reasonable doubt.

These cases highlight the challenges faced by the ICC in gathering sufficient evidence, obtaining witness cooperation, and establishing the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt. It is important to note that the ICC operates under strict legal standards, and the burden of proof rests on the prosecution to present credible evidence to secure convictions. When evidence is lacking or unreliable, it can result in challenges or failures in the prosecution’s case.

There have been criticisms and challenges related to cases involving Western countries. Some of the notable cases where the ICC’s involvement faced difficulties or criticism include:

- United States: The United States is not a member of the ICC and has taken measures to exempt itself and its citizens from the court’s jurisdiction. This has created a barrier to the ICC’s involvement in cases concerning alleged crimes committed by U.S. nationals, such as the Iraq War and the treatment of detainees at Guantanamo Bay.

- Afghanistan: The ICC faced obstacles in investigating alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Afghanistan due to lack of cooperation from the United States and other involved parties. In 2019, the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber rejected the Prosecutor’s request to open an investigation in Afghanistan, citing political and practical considerations.

- Palestine: The ICC’s investigation into the crimes committed in the occupied Palestinian territories has faced opposition and challenges from Israel and some Western countries, such as USA and UK. The ICC’s jurisdiction over this situation is disputed, and there have been efforts to undermine the investigation and prosecution of potential crimes, hence the legal inertia when it comes to prosecuting the allies of the “Master”.

These cases highlight the complexities and political dynamics that can hinder the ICC’s involvement in cases from the West. They also underscore the challenges of securing cooperation and addressing issues related to jurisdiction and political sensitivities.

While it is theoretically possible for ICC judges, like any individuals, to be susceptible to various forms of coercion or corruption, the ICC takes significant measures to ensure the independence, integrity, and security of its judges. These measures are designed to mitigate risks and protect judges from undue influence or threats.

- Independent Appointment Process: ICC judges are selected through a rigorous and independent process. They are elected by the Assembly of States Parties, the governing body of the ICC, based on their qualifications, expertise, and impartiality. The selection process aims to ensure the appointment of highly qualified individuals with integrity and a commitment to justice.

- Code of Conduct: ICC judges are bound by a Code of Judicial Ethics that outlines the ethical standards they must adhere to. The code emphasizes the principles of independence, impartiality, integrity, and confidentiality. It serves as a guide for judges’ conduct and helps safeguard against external pressures or inducements.

- Security Measures: The ICC takes the security of its judges and personnel seriously. Measures are in place to protect them from potential threats or acts of intimidation. The court works closely with host countries, international organizations, and specialized security units to ensure the safety and well-being of its judges and staff.

- Protection Mechanisms: The ICC has established mechanisms to provide support and protection to individuals involved in its proceedings, including judges, witnesses, victims, and their families. This includes provisions for confidentiality, secure communication channels, and, if necessary, relocation or witness protection programs.

While these safeguards are in place, it is important to recognize that no system is entirely immune to external influences or human fallibility. However, the ICC’s commitment to upholding the highest ethical standards, coupled with the security measures in place, aims to minimize the risks and vulnerabilities that judges may face. Instances of judges being compromised or influenced by external pressures would be highly detrimental to the credibility and integrity of the ICC. Therefore, the court and its member states have a vested interest in maintaining a robust and independent judiciary, capable of withstanding any attempts to compromise its functioning.

To strengthen its powers of jurisdiction, the International Criminal Court (ICC) can undertake several measures:

- Increased Ratification: The ICC’s jurisdiction is dependent on the ratification of the Rome Statute by states. Encouraging more countries to ratify the statute would expand the court’s reach and make it more effective in addressing crimes. The ICC can engage in diplomatic efforts to encourage non-ratifying states to join the court.

- Enhanced Cooperation: The ICC relies on the cooperation of member states and other relevant actors to carry out its investigations and prosecutions. Strengthening cooperation mechanisms and ensuring timely and full cooperation from states in providing access to evidence, witnesses, and suspects is crucial. The ICC can work towards building stronger partnerships with national governments and international organizations to facilitate this cooperation.

- Outreach and Awareness: Increasing public awareness about the ICC’s mandate, activities, and achievements can generate support and foster a better understanding of the importance of international justice. The court can engage in outreach programs, educational initiatives, and media campaigns to raise awareness and promote the ICC’s role in combating impunity.

- Addressing Impunity Challenges: The ICC can address challenges related to impunity by focusing on cases involving powerful individuals and influential states. It can prioritize investigations and prosecutions that have significant impact and send a strong message that impunity will not be tolerated, regardless of the perpetrator’s position or nationality.

- Strengthening Witness Protection: Ensuring the safety and protection of witnesses is crucial for the ICC’s investigations and trials. Enhancing witness protection programs, providing secure mechanisms for testimony, and offering support to witnesses and their families can encourage more individuals to come forward and cooperate with the court.

- Enhanced Judicial Capacity: Strengthening the ICC’s judicial capacity can contribute to more efficient and effective proceedings. This can involve providing additional resources, training programs for judges, and ensuring a diverse and highly qualified bench to handle cases.

- International Cooperation: Collaborating with regional and international organizations, such as Interpol, Europol, and other judicial bodies, can enhance the ICC’s ability to investigate and prosecute crimes. Sharing information, resources, and expertise can strengthen the court’s jurisdiction and facilitate cross-border cooperation.

- Review and Reform: Regularly reviewing the ICC’s operations and procedures, and implementing necessary reforms based on lessons learned and best practices, can enhance its efficiency, transparency, and credibility. This includes evaluating the effectiveness of the court’s investigations, prosecutions, and the functioning of its organs.

By implementing these measures, the ICC can strengthen its powers of jurisdiction, enhance its ability to hold perpetrators accountable, and contribute to the prevention of crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, and aggression.

The question often raised is what is the future of existence of ICC in the latter decades of the 21st century, as global belligerence increases, and non-compliance of nations becomes rampant, with great impunity? The future of the International Criminal Court (ICC) will depend on several factors, including the political will of states, global dynamics, and the continued relevance and effectiveness of the court in addressing international crimes. While there are challenges and criticisms facing the ICC, its existence and role in promoting accountability and justice remain significant. It is true that global belligerence and non-compliance by nations can pose challenges to the ICC’s effectiveness. The court relies on the cooperation of member states and other relevant actors to carry out its investigations and prosecutions. If powerful states continue to resist the court’s jurisdiction or impede its work, it could limit the ICC’s impact in addressing global crimes. However, it is important to recognize that the ICC operates within a complex international system, and its influence is not solely determined by the actions of individual states. The ICC’s legitimacy and relevance are bolstered by the increasing recognition of international criminal justice norms, the growing understanding of the importance of accountability, and the demand for justice by victims and affected communities. The ICC’s ability to adapt to changing dynamics and navigate geopolitical challenges will be crucial for its future. The court can work towards strengthening its investigative capacity, enhancing cooperation mechanisms, and improving efficiency in its proceedings. Additionally, building strong alliances with regional and international organizations, promoting universal ratification of the Rome Statute, and engaging in strategic diplomacy can further support the court’s mandate. Ultimately, the long-term future of the ICC will depend on the collective efforts of the international community to uphold the principles of justice, accountability, and the rule of law. As global challenges persist, it will be essential for states, civil society, and other stakeholders to continue supporting the ICC’s mission and advocating for the prevention and prosecution of international crimes.

In the 21st century, various types of crimes against humanity have been documented. It is important to note that the classification and categorisation of these crimes can vary, but here are some common types: