The Impact of Prehistoric Religious Rituals on Pillars of Peace (Part 4)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 17 Jul 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Humanity has dissipated its spirituality and is and has been fervently praying to diverse multitude of Religious Rituals, rather than the Divine Supreme.”[1]

The indigenous San communities of southern Africa were originally a community of hunters and gathers. However, one of the greatest testaments to San history is the rock art found throughout the subcontinent. Photo shows the detail of the ceiling of an African Cave Art painting. There are indications that of these drawings support the idea of spirituality, rituals and Peace Propagation, even 30,000 years ago.

Photo credit Courtesy © Stephen Townley Bassett

This paper, the fourth part in the series on “Pillars of Peace,” discusses the impact and contributions the Prehistoric Religious Rituals in general have made to the structure and spiritual fibre of the essence of individual, community and global peace, formalized in later emergence of the dominant religions of the world. This long journey is traced from the Paleolithic Period in evolution, in which the so called primitive modern human ancestors, roamed the earth, not only hunting and gathering food, but also engaging creative, artistic activities in the form of “Cave Art[2] or Rock Art[3] in their places of dwellings for protecting themselves from the natural and predatory elements in the primaeval forests.

It is only in recent years that it has been established that these Homo neanderthalensis[4] were as intelligent as modern human, had a large degree of spirituality, as well practised religious rituals, which was realised by using modern technological advances to highlight their psycho-social advancement. This is borne out and confirmed by the discovery of Neanderthal burial sites to indicate that these primitive humans also had an interconnectedness with something as a Divine Supreme, which on careful analyses using advanced, 21st century, proper research methodologies, is verified by multidisciplinary teams of researchers, who have revisited and re-examined the various Cave Art works, in different parts of the world.

The oldest rock art in southern Africa is around 30,000 years old and is found on painted stone slabs from the Apollo 11 rock shelter in Namibia[5]. Where our study took place, the Maloti-Drakensberg mountain massif of South Africa and Lesotho Unesco World Heritage Site[6], rock paintings were created from about 3,000 years ago right into the 1800s. For decades, people thought that one guess about the art’s meaning was as good as another. However, this ignored the San[7] themselves. We can deepen our understanding if we try to view rock art in terms of San shamanistic beliefs and experiences. Advances in ethnography (literature produced by anthropologists who work with San people) help convey San worldview to rock art researchers.[8] We re-investigated such a site in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg mountains[9]. It was first described in the 1950s and is recorded as RSA CHI1[10]. At first glance, the ceiling panel seems a confusing collection of paintings of antelopes and human figures, some of which are painted on top of others, in shades of earthy reds, yellow ochres and white.

In 2009 and working under challenging circumstances, South African artist and author Stephen Townley Bassett [11]produced a documentary copy of the ceiling panel. It shows the art’s beauty and mystery. When we looked at his copy, we found that the significance of some images on the site’s ceiling panel had been missed by other researchers. This allowed us to examine the meaning of these images more closely. Importantly, our realisation was not a technological or methodological advance. Instead, it was a conceptual development that occurred by turning our attention to a well-known site and viewing it again in the light of everything we have learned so far about San rock art. Our re-investigation allowed us to arrive at a new understanding of specific elements of San belief. Two sources of San ethnography [12]are especially important in rock art research and our understanding of the ceiling panel. In the 1870s, the German linguist Wilhelm Bleek [13]and his co-worker and sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd interviewed a series of |Xam San people[14], some of whom had been brought from the Northern Cape to Cape Town as convicts. Remarkably, Bleek and Lloyd recorded over 12,000 pages of texts in the |Xam language, which is no longer spoken, and transliterated most of it line-by-line into English. Much of this material remains relevant to our understanding of the art. More recently, in the twentieth century, a number of anthropologists worked with San groups in Namibia and Botswana with a focus on a range of topics from hunting and gathering to folklore and childcare. The Kalahari ethnography compliments the Bleek and Lloyd archive. We know from the ethnography that the San believe in a universe with spiritual realms above and below the level on which people live. Decades of research has shown that the rock art is deeply religious and situated conceptually in the same multilevel universe.

In San rock art, the eland is a connecting element. It is the most commonly depicted antelope in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg paintings. It features in several San rituals and was believed to be the creature with the most !gi:, the |Xam word for the invisible essence [15]that lies at the heart of San belief and ritual. At RSA CHI1, there are many depictions of eland, but we focused on the one with its head sharply raised. Depictions of this posture, though not common, recur in other sites. The eland’s raised head suggests that it is smelling something, most probably rain. Both smell and rain are supernaturally powerful in San thought. The unique feature in this paintings is, however, the way in which a line runs up from an area of rough rock, breaking at the eland’s front legs, and then on to another area of rough rock. The painter, or painters, must have depicted the eland first and then added the line to develop the significance of its raised head. We argue that both the raised head and the line emphasise contact with the spirit realm, though in different ways. The way in which the painted line emerges from and continues into areas of rough rock is comparable to the way in which numerous San images were painted to give the impression that they are entering and leaving the rock face via cracks, steps and other inequalities. But what lay behind the rock face? We have noted already that the San universe is divided into different realms. Contact between these often-interacting realms is sometimes depicted in the art by long lines that link images or sometimes appear to pass through the rock face. San shamans or medicine people (called !gi:ten in |Xam) move along or climb these ‘threads of light’ as they journey between realms to heal the sick, make rain and perform other tasks. The |Xam called these out-of-body journeys |xãũ. They obtained the power needed to accomplish them by summoning potency from strong things, such as the eland. The inter-realm nature of the line is further evidenced by the three creatures depicted moving along it. The two moving upward are quadrupeds or four-legged animals: one is non-specific and one has a tail and human arms. These images may depict the sort of bodily changes that !gi:ten say they experience during out-of-body journeys. The faint white creature moving down the line was for us the climax of our work. It is clearly birdlike (!gi:ten often speak of flying). But closer inspection revealed that, though faint, it has a rhebok antelope head with two straight black horns, a black nose and mouth. It also has two ‘wings’ emanating from its shoulders. In short, it is a hybrid form – part bird and part buck. In addition, it has two white lines coming out of the back of its neck. It was from this spot that !gi:ten expelled the sickness that they drew out of the bodies of sick people. For many people, the detail and the complexity of the images at this site come as a surprise. Yet they are typical. San rock art ranks among the best in the world if we consider its beauty, its intricacy and the rich sources of explanation on which we can draw.[16]

The oldest known cave painting is a red hand stencil in Maltravieso cave, Cáceres, Spain.[17] It has been dated using the uranium-thorium method to older than 64,000 years and was made by a Neanderthal. The oldest date given to an animal cave painting is now a depiction of several human figures hunting pigs in the caves in the Maros-Pangkep karst of South Sulawesi, Indonesia[18], dated to be over 43,900 years old.[12] Before this, the oldest known figurative cave paintings were that of a bull dated to 40,000 years, at Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave, East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo,[19] and a depiction of a pig with a minimum age of 35,400 years at Timpuseng cave in Sulawesi.[20] The burial practices of Neanderthals, which involved intentional burial of their dead and sometimes accompanying grave goods, do indicate a degree of spirituality and a belief in an afterlife or a connection with a higher realm. While we cannot fully ascertain the precise spiritual or religious beliefs of Neanderthals, their burial practices suggest a recognition of the significance of death and an understanding that it involved more than just the physical body. The act of burying the dead with care and offering grave goods implies a belief in an existence beyond death and a sense of respect or reverence for the deceased. These practices also indicate a level of social cohesion and possibly the belief in communal rituals and an interconnectedness with the spiritual or divine realm. While direct evidence of Neanderthal spirituality is not available, their burial practices, along with other aspects of their culture and behaviour, suggest a deeper understanding and engagement with the concepts of life, death, and possibly the pursuit of peace or harmony within their social groups. It highlights their cognitive and emotional capacities, as well as their capacity for symbolic thinking and ritualistic behaviour.

Another interesting aspect of “Rock Art” are the “Petroglyphs”[21]. They are indeed a form of rock art. Petroglyphs are designs or symbols that have been carved, pecked, or incised into rock surfaces. A petroglyph is an image that is carved into a rock. This “carving” can produce a visible indentation in the rock or it can simply be the scratching away of a weathered surface to reveal unweathered material of a different colour below. It is not a “drawing” or a “painting”, which are classified as “pictographs[22]. The petroglyphs are created by removing the outer layer of the rock to reveal the lighter underlying rock, creating a contrast in colour or texture. Petroglyphs are found in various parts of the world and have been created by different cultures throughout history. They often depict a wide range of subjects, including animals, humans, abstract designs, symbols, and cultural or spiritual motifs. Like other forms of rock art, petroglyphs serve as a means of communication and expression for the cultures that created them, including spirituality. They can convey important cultural, religious, or symbolic meanings, providing insights into the beliefs, experiences, and cultural practices of the people who made them. The creation of petroglyphs requires time, skill, and intentionality, as the designs are intentionally carved or engraved onto the rock surface. Petroglyphs are typically found in outdoor environments, such as rock shelters, caves, or exposed rock faces, often in areas of cultural significance or natural beauty. Studying petroglyphs can provide valuable insights into the ancient cultures that created them, including their artistic traditions, spiritual beliefs, and connections to the natural world. They contribute to our understanding of human history, culture, and artistic expression.

Petroglyph Carvings in a limestone cave on Chatham Islands show where Moriori took shelter. The human is included for comparison in size of the Petroglyphs. These rock carvings have a deep spiritual and ritualistic meaning which has not yet been elucidated by researchers. Picture / Richard Robinson

The author has visited Chatham Islands[23] in the Pacific in 2000, and studied the petroglyphs found in these remove, isolated, Pacific Islands. The Chatham Islands, have a rich cultural heritage, including the presence of petroglyphs. Petroglyphs on the Chatham Islands are known for their unique artistic style and cultural significance. The petroglyphs found on the Chatham Islands often depict various motifs, including human figures, animals, birds, and geometric designs. These carvings are typically made on hard basalt rocks, using stone tools to incise or peck the designs onto the surface. The specific meanings and interpretations of the Chatham Islands’ petroglyphs are not fully understood, as there is limited written historical documentation about the indigenous culture that produced them. However, they are believed to hold cultural, spiritual, and symbolic significance for the Chatham Islands’ ancestral communities. The petroglyphs in the Chatham Islands provide valuable insights into the ancient culture and artistic expressions of the people who inhabited the islands in the past. They are considered important archaeological and cultural heritage sites, showcasing the creative abilities and cultural traditions of the indigenous communities. Studying and preserving these petroglyphs contribute to our understanding of the history, traditions, and connections between people and the landscape in the Chatham Islands. They provide a window into the cultural richness and artistic expressions of the past, fostering appreciation and knowledge about the indigenous heritage of the region. The people who created the petroglyphs in the Chatham Islands were likely the Moriori[24], an indigenous Polynesian people who inhabited the Chatham Islands. The Moriori people have a distinct cultural and linguistic heritage separate from other Polynesian[25] groups. Determining the exact age of the Chatham Islands’ petroglyphs can be challenging, as accurate dating methods for rock art are often difficult to apply. However, based on archaeological research and comparative analysis with other sites, it is estimated that some of the petroglyphs on the Chatham Islands could be several hundred to thousands of years old. The precise purpose and significance of the petroglyphs are not fully known, as they were created by an ancestral culture that did not leave behind written records. However, they are believed to have held cultural and spiritual importance, potentially representing aspects of the natural environment, ancestral figures, or significant events within the Moriori worldview. Further archaeological research and studies are necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the Chatham Islands’ petroglyphs and their cultural context. Ongoing efforts to document, preserve, and interpret these ancient carvings contribute to our knowledge of the Moriori culture and the unique artistic expressions of the Chatham Islands. The petroglyphs found on the Chatham Islands may have been created by the Moriori or by even earlier inhabitants of the islands. These carvings could hold cultural, spiritual, or symbolic significance for the indigenous communities that lived there in the past. Studying the petroglyphs, along with other archaeological evidence, can provide insights into the diverse and complex history of human occupation on the Chatham Islands. It allows us to better understand the cultural expressions, religious beliefs, and practices of the people who lived there before and during the time of the Maori arrival[26] and the genocide of the Chatham Island Mariori.[27]

There are petroglyphs found in various parts of the three main islands that make up the present-day country of New Zealand (North Island, South Island, and Stewart Island[28]). These petroglyphs are attributed to the indigenous Maori people and reflect their cultural and artistic heritage. The Maori petroglyphs in New Zealand are primarily found in areas of cultural significance, such as rock shelters, caves, or cliff faces. They are often carved or pecked into the rock surfaces using stone tools, depicting a variety of symbols, figures, animals, and cultural motifs. One notable site with Maori petroglyphs is the Whakarewarewa Thermal Valley in Rotorua[29], located in the North Island of New Zealand. This site features carvings on rocks that depict ancestral figures, traditional symbols, and spiritual designs. These petroglyphs are believed to have cultural and spiritual significance for the local Maori community. It is to be noted that petroglyphs in New Zealand, as in other parts of the world, are subject to preservation efforts and cultural protocols. Some petroglyph sites may be protected, and access to them may require permission or guided tours to ensure their conservation and respect for cultural heritage. The origins and meanings of the petroglyphs found on the Chatham Islands, including those created by the Moriori people, can be complex and challenging to decipher. It is important to note that the Chatham Islands’ petroglyphs are distinct from hieroglyphics, which are a form of writing system used in ancient Egypt. Unlike hieroglyphics, which have been deciphered thanks to the Rosetta Stone [30]and the efforts of linguists and scholars, the petroglyphs found on the Chatham Islands have not been fully deciphered or understood in terms of their specific meanings or language. The symbols and designs used in these petroglyphs may have held significant cultural and spiritual meaning for the people who created them, but without a known script or bilingual text, it is challenging to interpret them definitively. Analysing these petroglyphs requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining archaeological evidence, comparative studies with other cultural artefacts, and consultation with indigenous communities who may have knowledge of their cultural traditions. Ongoing research and collaboration with local communities are crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of the Chatham Islands’ petroglyphs. It is worth noting that efforts are being made to preserve and document these petroglyphs, and some progress has been made in identifying patterns, motifs, and potential cultural associations. However, fully comprehending their specific language or meaning remains a complex task that requires further research and engagement with the cultural context of the Chatham Islands’ indigenous communities.

Chatham Island also has the sites of Dendroglyphs[31], which the author has studied. A dendroglyph is a term used to describe a type of cultural or historical mark made on trees. It refers to carvings, inscriptions, or other forms of markings made on tree trunks or branches by people in the past.

Chatham Island Dendroglyphs : Early Moriori carved designs of people and their surroundings on kopi (karaka) trees. Nicole Whaitiri, aged 10, who is of Moriori descent, looks at this example in 2010. Such carvings are estimated to be up to 300 years old. The trees, and therefore the carvings, are unlikely to survive much longer due to disease and wind erosion. A joint Department of Conservation and University of Otago, New Zealand, team digitally scanned 98 carvings on 93 trees as a way to preserve them. These could be analysed using Artificial Intelligence to understand their deep significance.

Dendroglyphs can be found in various parts of the world and have been created by different cultures throughout history. They serve as a form of artistic expression, communication, or documentation of significant events or symbols of spiritual or religious rituals. The carvings may include patterns, symbols, images, or text, providing insights into the cultural practices, beliefs, or history of the people who created them. In some cases, dendroglyphs have been found in archaeological contexts, offering valuable information about past societies. They can provide clues about ancient trade routes, religious practices, territorial markers, or even personal messages. Dendroglyphs are often studied by archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians to better understand the cultural and historical contexts in which they were created. Importantly, dendroglyphs are considered cultural artefacts and should be treated with respect and preservation efforts. In many regions, there are laws and regulations in place to protect these ancient carvings on trees, as they are part of our shared heritage and cultural history.

Therefore, it is clearly evident from the cave paintings, using recent advances in dating technologies, that the ancestors of modern humans, were spiritually inclined and had some for of worship, as a religious ritual, to glorify and seek assistance in their daily lives, be it provision of food, or protection, from and by the Divine Supreme. He difference is that recent interpretations of Cave and Rock arts reveals that they have the significance of a religious ritual, dating back to the Neanderthals. The Rock Art and its spiritual motivation, conjures up connotations of “Communal Inter-Cave Peace” as a religious ritual!

There are also these rock art sites found in various parts of South America and North America that predate the Aztecs[32], Mayans[33], Incas[34], and the indigenous peoples of North America. These rock art sites provide valuable insights into the ancient cultures and artistic traditions that existed in these regions before the arrival of European settlers.

In South America, one notable example of ancient rock art is found in the Serranía de la Lindosa region of Colombia[35], where researchers have discovered a large number of rock paintings in remote caves. These paintings depict a variety of subjects, including animals, humans, and geometric patterns. The exact age of these rock art sites is still being determined, but some estimates suggest they may date back several thousand years.

In North America, there are numerous rock art sites that were created by indigenous peoples before European contact. These include the petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings) found in various regions, such as the Southwest United States, California, the Great Basin, and the Canadian Shield[36]. These rock art sites often depict figures, animals, symbols, and scenes that hold cultural and spiritual significance for the indigenous communities who created them. It must be remembered that dating rock art can be challenging, as it often requires a combination of scientific techniques and contextual analysis. The exact age of many rock art sites in South America and North America is still being researched and refined. Nonetheless, these ancient rock art sites provide valuable glimpses into the artistic and cultural traditions of the diverse ancient civilizations that inhabited these regions.

It is necessary to highlight the uranium-thorium dating method is a radiometric dating technique used to determine the age of calcium carbonate materials, such as stalagmites, corals, and certain cave deposits, which can be found in ancient artefacts.

Uranium-thorium dating[37] relies on the radioactive decay of uranium-238 to thorium-230. Uranium-238 is present in trace amounts in the environment and can be incorporated into calcium carbonate over time. Once the calcium carbonate is formed, it begins to accumulate thorium-230 through radioactive decay. The dating process involves measuring the ratio of uranium-238 to thorium-230 in the sample. Since uranium-238 decays at a known rate, the ratio of the two isotopes can be used to estimate the age of the sample. The uranium-thorium dating method is particularly useful for dating artefacts that are older than about 50,000 years, which is beyond the limit of radiocarbon dating. It is often used for dating cave formations, such as stalagmites and flowstones, as well as coral reefs and other marine deposits. It is also important to note that uranium-thorium dating is a complex technique that requires careful sample collection and laboratory analysis. The dating results are typically reported as an age range, considering various sources of uncertainty and potential complications in the dating process.

Religious rituals and Secular rituals are two terms that are often confused when it comes to their definitions and meanings. Religious rituals have symbolic value attached to them. They are normally prescribed and defined by a particular religion. All religious celebrations come under religious rituals. Religious rituals include worship rites, sacraments of organised religions, atonement and purification rites, coronations, dedication ceremonies, marriage and funereal customs. On the other hand, secular rituals include day to day activities and actions.

The Bottom Line is that, the general rituals, as practised by the main monotheistic and polytheistic religions of the world have their origins in antiquity, the author proposes that the origins of these religious rituals go beyond that era, to prehistory from the time of the appearance of the Neanderthals in the evolution of humans at least 64,000 years ago. The hypothesis is based on the spiritual associations of the figures and illustrations observed in the Cave Art and Rock Art, in Southern Africa, as well as other parts of the world. Recent research and review of the original Rock Art, paintings, as a part of a multidisciplinary team, using modern and highly advanced dating technology, together with a disregards of an Eurocentric approach, that “nothing good comes out of Africa” emphasising a broader Afrocentric culture and understating of the traditions of the San people, in recent decades, has enabled a deeper understanding of the significance of the Cave Art paintings in sub Saharan Africa and indeed the rest of the world where these art forms have been discovered, by cave explorers, photographers, paleo-anthropologists and even construction worker on major civil projects such and mountain passes, bridges and roads railways and mining. In various parts of the world. The complete narrative of the serendipitous discovery of the Taung skull[38] emphases this vary aspect of literally ground-breaking, “earth-shattering” anthropological discoveries over the decades, especially in Africa, the Cradle of Humankind[39]. To add to this origin of religious rituals from Cave Art, the discovery of Petroglyphs has also stimulated great debate in terms of the spiritual significance of these pictorial carvings by indigenous peoples in different parts of the world. These petroglyphs, it is proposed could also be a part of complex, prehistoric, the labours of carving these in hard rock, was probably based on love for the Divine Supreme and as a peace propagation effort, in general.

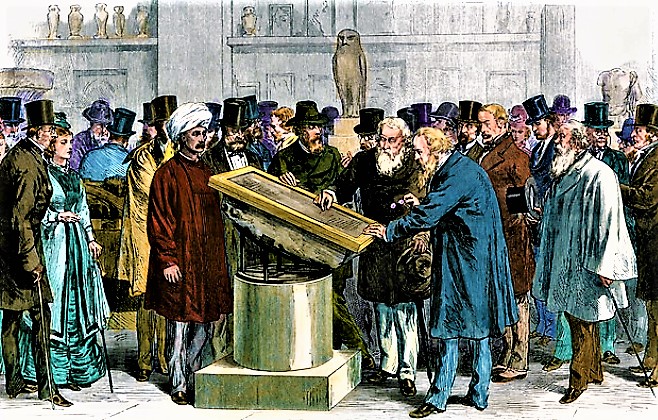

Current high technology research, using Artificial Intelligence[40] to analyse petroglyphs to decipher them as a language, similar to the decipherment of hieroglyphics with the Rosetta Stone[41], is a complex and ongoing field of study. The Rosetta Stone itself contains an edict or decree issued by a child Pharaoh and was meant as a religious ritual by the high priests of Egypt to ensure peace during the reign of the child King Ptolemy V[42], in 196 BC at Memphis. While Artificial Intelligence technologies can assist in pattern recognition an data analysis, the interpretation of petroglyphs involves various challenges that make it different from deciphering a known script like hieroglyphics. One of the primary challenges is the lack of a bilingual or trilingual text, like the Rosetta Stone, that provides a key to understanding the petroglyphs. In the case of hieroglyphics, the Rosetta Stone contained the same text in three different scripts, allowing researchers to match the symbols with known translations.

Petroglyphs, on the other hand, often lack a known script or linguistic context. The meanings of the symbols or designs may vary across different cultural groups and time periods, making it difficult to develop a universal algorithm for interpretation. Albeit, the message I clear, any form of Rock and Cave Art, created by prehistoric people, reflects on these cultures as having an interconnectedness with the spiritual world, in developing a “BRIDGE” like what the modern cultures attribute to shamanism[43]. These are the very origins of the ancient rituals in different religions, which are practiced in the present state of post modernism, in all religions. This is achieved, incorporating syncretism[44], social evolution, and appeasement mortal powers that be as well as the Supreme Divine, in the process.

However, researchers are exploring innovative approaches to analysing and interpreting, Rock Art and petroglyphs using Artificial Intelligence and other computational methods. Machine learning techniques, such as image recognition algorithms and pattern analysis, can help identify recurring motifs, classify symbols, and detect possible associations between petroglyphs and cultural contexts.

While Artificial Intelligence can assist in processing and analysing large datasets of petroglyphs, the interpretation and understanding of their specific meanings still require interdisciplinary collaboration involving archaeologists, anthropologists, linguists, and indigenous communities. It is a complex and ongoing endeavour that combines technological advancements with cultural and contextual expertise. As research and technology continue to advance, it is possible that AI and computational methods will play a role in furthering our understanding of petroglyphs. However, it is important to approach the analysis and interpretation of these cultural artefacts with respect for indigenous knowledge[45], cultural protocols, and community involvement.

References:

[1] Personal quote by the author, June 2023

[2] https://www.theartstory.org/movement/cave-art/#:~:text=Cave%20Art%20(or%20Paleolithic%20Art,combination%20of%20man%20and%20beast.

[3] https://www.southafrica.net/gl/en/travel/article/rock-art-in-south-africa

[4] http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/homo-neanderthalensis

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_11_Cave

[6] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/985/#:~:text=The%20Maloti%2DDrakensberg%20Park%20World,242%2C813%20ha)%20in%20South%20Africa.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_people

[8] https://theconversation.com/an-ancient-san-rock-art-mural-in-south-africa-reveals-new-meaning-157177

[9] https://www.nature-reserve.co.za/ukhahlamba-drakensberg-wildlife-preserve.html

[10] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0067270X.2020.1868757

[11] https://www.stb-rockart.co.za/

[12] https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/san/hd_san.htm

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Bleek

[14] https://www.krugerpark.co.za/africa_bushmen.html

[15] https://theconversation.com/an-ancient-san-rock-art-mural-in-south-africa-reveals-new-meaning-157177

[16] https://theconversation.com/an-ancient-san-rock-art-mural-in-south-africa-reveals-new-meaning-157177

[17] https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/cave-of-maltravieso

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caves_in_the_Maros-Pangkep_karst

[19] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/worlds-oldest-known-figurative-paintings-discovered-borneo-cave-180970747/

[20] http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/prehistoric/sulawesi-cave-art.htm

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petroglyph

[22] https://geology.com/articles/petroglyphs/more-petroglyphs.shtml

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chatham_Islands

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moriori

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polynesians

[26] https://www.jstor.org/stable/20701278

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moriori_genocide#:~:text=The%20Moriori%20genocide%20was%20the,1835%20to%20the%20early%201860s.

[28] https://www.stewartisland.co.nz/

[29] https://whakarewarewa.com/geothermal/#:~:text=Whakarewarewa%20Valley%20is%20an%20active,that%20lay%20beneath%20their%20feet.

[30] https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/everything-you-ever-wanted-know-about-rosetta-stone#:~:text=The%20Rosetta%20Stone%20is%20thus,and%20the%20names%20were%20changed!

[31] https://www.thefreedictionary.com/dendroglyph

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Aztecs#:~:text=The%20Aztecs%20were%20a%20Pre,raised%20island%20in%20Lake%20Texcoco.

[33] https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-americas/maya

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Incas#:~:text=The%20Inca%20people%20began%20as,began%20a%20far%2Dreaching%20expansion.

[35] https://www.sdcelarbritishmuseum.org/projects/the-serrania-la-lindosa-new-archaeological-sites-for-the-colonisation-and-settlements-of-the-colombian-amazon/

[36] https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/shield#:~:text=The%20Canadian%20Shield’s%20most%20notable,during%20the%20last%20ice%20age.

[37] https://isobarscience.com/what-is-u-th-dating/#:~:text=What%20is%20Uranium-Thorium%20Dating%3F%20U-Th%20dating%20is%20an,rock%2C%20corals%2C%20shells%20and%20%28in%20some%20cases%29%20bones.

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taung_Child#:~:text=The%20Taung%20Child%20(or%20Taung,the%20journal%20Nature%20in%201925.

[39] https://www.maropeng.co.za/content/page/introduction-to-your-visit-to-the-cradle-of-humankind-world-heritage-site

[40] https://www.ibm.com/topics/artificial-intelligence#:~:text=At%20its%20simplest%20form%2C%20artificial,in%20conjunction%20with%20artificial%20intelligence.

[41] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Rosetta%20stone#:~:text=1,gives%20a%20clue%20to%20understanding

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosetta_Stone_decree

[43] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332109634_Shamanism_and_the_Origins_of_Spirituality_and_Ritual_Healing

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religious_syncretism

[45] https://www.bioeconomy.co.za/indigenous-knowledge#:~:text=IKS%20can%20be%20broadly%20defined,stable%20livelihoods%20in%20their%20environment.

______________________________________________

READ: PART 1 – PART 2 – PART 3 – PART 5

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: History, Peace, Peace Culture, Peace Education, Peace Studies, Peacebuilding, Philosophy, Religion, Spirituality

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 17 Jul 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Impact of Prehistoric Religious Rituals on Pillars of Peace (Part 4), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.