Japan Releases Nuclear Wastewater into the Pacific. How Worried Should We Be?

ENVIRONMENT, 28 Aug 2023

Lesley M.M. Blume | National Geographic - TRANSCEND Media Service

The plan to gradually discharge more than a million tons of treated radioactive water from the crippled Fukushima nuclear plant has started–deeply dividing nations and scientists.

More than a million tons of treated wastewater are stored in tanks at the plant. Without more storage capacity, Japan says it has no choice other than to release the water gradually into the ocean.

Photograph by The Asahi Shimbun/Getty

24 Aug 2023 – Japan has started releasing wastewater into the ocean. But this isn’t the kind of wastewater that flows from city streets into stormwater drains. It’s treated nuclear wastewater used to cool damaged reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, stricken by an earthquake over a decade ago.

Japan claims that the wastewater, containing a radioactive isotope called tritium and possibly other radioactive traces, will be safe. Neighboring countries and other experts say it poses an environmental threat that will last generations and may affect ecosystems all the way to North America. Who is right?

Following a 9.1-magnitude quake off the east coast of Japan’s main island on March 11, 2011, two tsunami waves slammed into the nuclear plant. As three of its reactors melted down, operators began pumping seawater into them to cool melted fuel. More than 12 years later, the ongoing cooling process produces more than 130 tons of contaminated water daily.

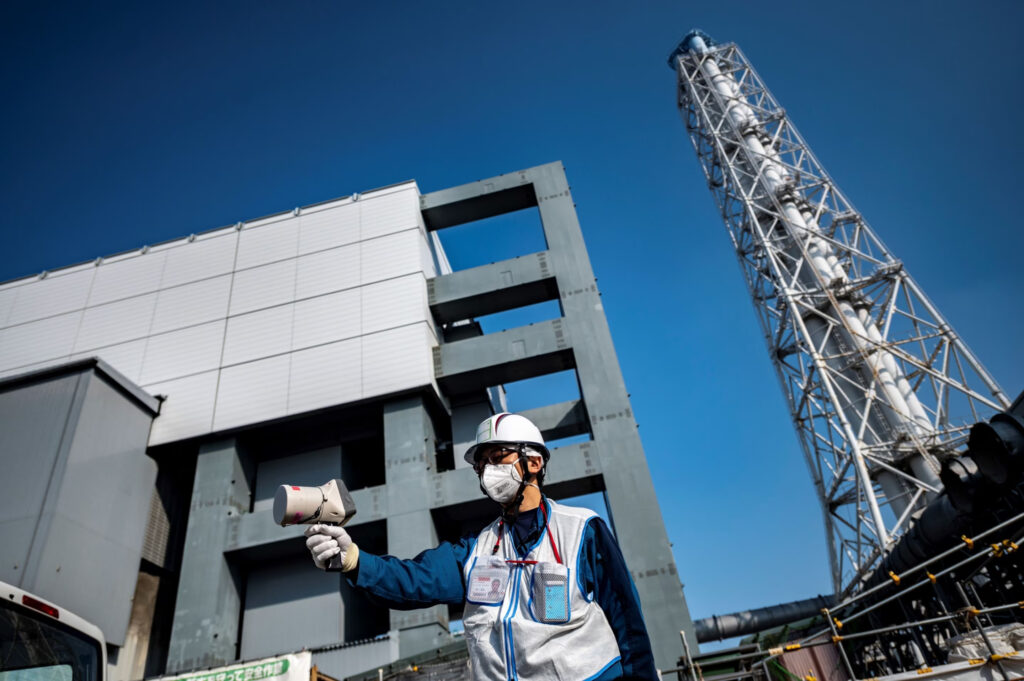

On February 21, 2021, a Tokyo Electric Power Company employee measures radiation outside its Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, devastated a decade ago by an earthquake. Japan’s planned releases of wastewater used to cool damaged reactors is stirring controversy.

Photograph by Philip Fong, AFP/Getty

Since the accident, over 1.3 million tons of nuclear wastewater have been collected, treated, and stored in a tank farm at the plant. That storage space is about to run out, the Japanese government says, leaving no choice other than to begin dispensing the wastewater into the Pacific.

Japan’s discharge plan involves incrementally releasing it over the next three decades, although some experts say it could take longer, given the amount still being produced. While the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)—the UN’s nuclear watchdog—assesses the plan’s safety, some of Japan’s neighbors are criticizing it as unilateral and dangerous. A senior Chinese official recently called it a risk “to all mankind” and accused Japan of using the Pacific as a “sewer.” The head of the Pacific Islands Forum, an organization representing 18 island nations (some already traumatized by decades of nuclear testing in the region) dubbed it a Pandora’s box. On May 15, South Korea’s opposition leader derided Japanese leaders’ claims that the water is safe enough to drink: “If it is safe enough to drink, they should use it as drinking water.”

Now, American scientists are raising concerns that marine life and ocean currents could carry harmful radioactive isotopes—also called radionuclides—across the entire Pacific Ocean.

“It’s a trans-boundary and trans-generational event,” says Robert Richmond, director of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory at the University of Hawaii, and a scientific adviser on the discharge plan to the Pacific Islands Forum. “Anything released into the ocean off of Fukushima is not going to stay in one place.”

Richmond cites studies showing that radionuclides and debris released during the initial Fukushima accident were quickly detected nearly 5,500 miles away off the coast of California. Radioactive elements in the planned wastewater discharges may once again spread across the ocean, he says.

The radionuclides could be carried by ocean currents, especially the cross-Pacific Kuroshio current. Marine animals that migrate great distances could spread them too. One 2012 study cites “unequivocal evidence” that Pacific bluefin tuna carrying Fukushima-derived radionuclides reached the San Diego coast within six months of the 2011 accident. No less worrying as carriers, Richmond says, are phytoplankton—free-floating organisms that are the basis of the food chain for all marine life and can capture radionuclides from the Fukushima cooling water. When ingested, those isotopes may “accumulate in a variety of invertebrates, fish, marine mammals, and humans.” In addition, a study earlier this year refers to microplastics—tiny plastic particles that are increasingly widespread in the oceans—as a possible “Trojan horse” of radionuclide transport.

Ocean currents could carry treated radioactive wastewater far from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Scientists in some countries around the Pacific worry about its potential effects on food chains and ecosystems.

Richmond and his colleagues are not the only American scientists urgently raising such concerns. This past December, the United States-based National Association of Marine Laboratories—an organization with more than a hundred member labs in the U.S. or U.S. territories—released a statement opposing the wastewater release plan. It cited “a lack of adequate and accurate scientific data supporting Japan’s assertion of safety.” The discharges, the statement said, may threaten the “largest continuous body of water on the planet, containing the greatest biomass of organisms … including 70 percent of the world’s fisheries.”

‘We’re Not Going to Die’

The releases need to be viewed in perspective, says Ken Buesseler, a marine radiochemist and adviser to the Pacific Islands Forum. The 2011 accidental release of radioactive materials from Fukushima into the Pacific was comparatively massive, he says, but even so, the levels detected off the west coast of North America “were millions of times lower than the peak levels off Japan, which were dangerously high in the first months of 2011.”

Because distance and time lower radioactivity levels, “I don’t think that the releases would irreparably destroy the Pacific Ocean,” Buesseler says. “We’re not going to die. This isn’t that situation.”

But, he adds, it “doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be concerned.”

The stored wastewater age tanks contains varying levels of radioactive isotopes such as cesium-137, strontium-90, and tritium, says Buesseler, who questions how effective the wastewater filtration system is at eliminating all radioactive elements in the tanks. The Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the nuclear plant’s owner and operator, uses a system that the IAEA says removes 62 different kinds of radionuclide isotopes, except tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen.

A TEPCO spokesperson said in an email that the impact of the discharges on “the public and the environment will be minimal.” All wastewater will be “repeatedly purified, sampled, and retested to confirm that the concentrations of radioactive substances fall below regulatory standards” before being released. Although the filtration system can’t remove tritium, the treated wastewater will be diluted with seawater until the discharges contain lower tritium levels than are released “by other nuclear power stations both in Japan and around the world,” according to the spokesperson. (Tritium is a comparatively weak isotope that can’t penetrate the skin but can be harmful when ingested.)

Buesseler cautions that the filtration system has not yet “been shown to be effective all of the time.” He says there are other “highly concerning elements … that they haven’t been able to clean up,” such as cesium and strontium-90, an isotope that increases risks of bone cancer and leukemia, earning it the sinister designation of “bone seeker.”

After examining TEPCO’s data on some of the wastewater storage tanks, Buesseler and his colleagues say that after treatment, the wastewater still contained radioactive isotopes whose levels varied significantly from tank to tank. “It’s unfair to say that they’ve been successfully removed,” he says.

The U.S. and U.N. Seem Poised to Support the Discharges

Asked about the United States’s position on Japan’s proposed discharges, a State Department spokesperson expressed cautious support, saying in a statement that the country has been “transparent about its decision, and appears to have adopted an approach in accordance with globally accepted nuclear safety standards.” The spokesperson declined to comment on specific concerns about the possible spread of radionuclides across the Pacific to North American shores. Representatives for Canada’s and Mexico’s foreign ministries did not respond to multiple requests for comment about that.

A task force from the International Atomic Energy Agency is reviewing the intended wastewater releases against international safety standards and is expected to release a report in late June detailing its final assessment. The plan is “in line with practice globally,” said Rafael Mariano Grossi, the agency’s director general, in 2021. “Our cooperation and our presence will help build confidence—in Japan and beyond—that the water disposal is carried out without an adverse impact on human health and the environment.”

Richmond and Buesseler say that although they’ve been privy to much of the same data as the IAEA, and have met with representatives from TEPCO and the Japanese government, they remain skeptical.

“The root of this problem is that they are moving already with a plan that has not yet shown that it will work,” Buesseler says. “They’re saying, ‘We can make it work. We’ll treat it as many times as it takes.’ If you want to put a nickname on this plan, it’s ‘trust us; we’ll take care of it.’”

Go to Original – nationalgeographic.com

Tags: Ecology, Environment, Fukushima, Japan, Nuclear Disaster, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Meltdown, Oceans, Pacific Ocean, Radioactive Waste, Science

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

In 2018, the researchers at Kinki University (= Kindai University) developed a revolutionary technology that removes tritium from the radioactive tritium water. Unfortunately, both Japanese Government and TEPCO have ignored it.

– (28 June 2018) https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/06/28/national/science-health/radioactive-tritium-removed-water-kindai-university-team-raising-hopes-fukushima-cleanup/

– (28 August 2018) https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20180828/p2a/00m/0na/013000c

However, TEPCO (whose main owner is the Japanese Government) has decided to simply dilute the radioactive tritium water with the sea water below the IAEA standard and to release it into the Pacific Ocean. The diluted tritium water is called, the “treated water”.

Why did TEPCO not use Kinki University’s technology? It was probably because it was easier for TEPCO to simply dilute the radioactive tritium water in accordance with IAEA’s standard. Was it troublesome for TEPCO to use Kinki University’s technology?

The discharge of the “treated water” will continue for next thirty years or more, according to TEPCO. What will it be the long-term effect of the discharge of the “treated water” into the Ocean?