South Africa, My Birthplace, Still Weeping: Coffin on Wheels (Part 2)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 21 Aug 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

This publication contains graphic images, which may be disturbing to some readers.

The Black, Minibus Taxis in South Africa keep the entire “Rainbow Nation” not weeping, but wailing.[1]

This paper, discusses the how the Black, mass transport system, from the historical, residential townships, designated by the nationalist apartheid government in South Africa, to their places of work, in the central business districts of major South African cities, have resulted in the Rainbow Nation still weeping from the social, cultural, health and economic impact of these Toyota Hiace Minibuses [2]certified to carry 15 passengers, often carrying twenty or more adult commuters, on a daily basis, officially for the past 42 years as “Coffin on Wheels”[3]. These vehicles, are often the cause of major Peace Disruption, not only due to serious and fatal road traffic accidents, which ruins the victims lives forever, but also having an impact on other sectors of the general lives of all South African, in the process, from the very rich. to the street dweller, who is crushed to death or maimed for life, as a pedestrian by these vehicles made in Durban South Africa. solely as a mass transit system for the Black people of the Rainbow Nation.

According to an “ode to the minibus taxis” by Zaza HlalethwaIt[4], a reporter for Mail and Guardian, of 20th April 2018, it all began in the year 1930 when the Motor Carrier Transportation Act of 1930 was passed, by the South African Government[5], following the Road Motor Commission in 1929 [6], the government saw South Africa’s transportation system as being disorderly, unrestricted and uncontrolled. To solve this, the commission’s chairperson, JC le Roux, recommended that all public transport be subjected to public sector ownership and regulation to eliminate competition[7].

Under the 1930 legislation, the carrying of goods or passengers with the goal of making a profit became illegal without a permit. The ownership and management of transportation facilities by Black people was considered an offence, and black people were denied permits to operate the vehicles, denying them entrepreneurial opportunities in the transit industry.

With the swipe of a pen, black bus operators and owners became illegal. Emerging black bus and taxi owners were forced to surrender their businesses to emerging white entrepreneurs in the transport sector and the “weeping of the Black people began”. But “your ancestors, o’ minibus taxi’ defied their circumstances and decided to operate illegally.

Because buses would attract the attention of officials, aboMalume, noAuntie camouflaged their taxi services using sedans, like Uber and Taxify do today, in the 21st century, except they managed to flourish without the auxiliary of app-armed smartphones.

The sedans they used were American cars such as Chryslers, Dodges and ones like Mkhulu’s Six Mabone[8]. These were big, allowing drivers to transport up to six adults while blending in with the general traffic. So, what looked like a large family travelling from point A to B was actually a group of commuting strangers and a driver.

By 1945, the state-owned companies that inherited buses operated and owned by black people merged to form the Public Utility Company, which we know as Putco[9] today.

Because it was a White owned, government, monopoly, Putco increased fares as it pleased. Seeing that the majority of its users were the black middle and working class, the inflated prices were one of the factors that triggered the Alexandra[10] and Evaton bus boycotts[11] in South Africa, that took place in 1956. Government subsidies for public transport became too expensive because of the rapid growth in demand. Buses and trains began to operate only during peak times with inflexible routes. Their demise was the nutrition that filled the taxi industry’s belly because it allowed your family to respond to commuters’ demands.

Things got worse for the state in the 1960s when my ancestors were removed from commercial and industrial hubs of employment by forced removals. In areas such as Hammanskraal, north of Pretoria[12], where my mother was raised, black workers commuting to central Pretoria[13] tripled by the 1970s.

Your family’s availability to transport the far-removed black working class using sedans is how it established itself as an important feature of the economy.

But the increased demand from consumers in townships and Bantustans, along with economic sanctions, resulted in a decreased availability of American sedans[14].

A plan for bigger and more accessible vehicles had to be made. It was in this period that your parents, the 10-seater Toyota Hi-Ace minibuses[15], were conceived and birthed.

This messed with the state’s profit so more legislation was put into place to cut off the taxi industry’s supply. The Van Breda Commission[16] was established to reject the competition you presented to state-run transportation, with the excuse that competition could lead to an oversupply. This commission advised on the draft Road Transportation Bill[17] to provide a system of control for unauthorised road transportation, essentially targeting your family.

The Road Transportation Act of 1977[18] defined a bus as a vehicle that carried more than nine people. So all drivers with vehicles that transported 10 commuters needed a permit.

The family did not hold their breath because clever people like aboMalume[19] Jimmy Sojane [20]and Pat Mbatha[21], who were prominent leaders in your family, overcame the hurdle by leaving one seat in the 10-seater Toyota Hi-Ace empty in order to operate legally.

Even when the demand was too much for state-run transportation, the authorities continued to make the process of acquiring permits hostile. Even when black operators had only nine passengers, they were subjected to fines and had to give up their vehicles if they were found without permits.

When this failed, your many homes were barricaded by traffic departments. So your operators no longer had the luxury of parking in designated areas to load and offload commuters.

Without a home base, the informal stop-and-go practice was born. Today, commuters flag you down, using a variety of hand signals. To get off, they holler “Mo robotong!” “Short left!” or “After hump!” to signal to the driver that they should stop.

With every load, the commuters’ destinations are different and thus minibus taxi operators made it impossible for traffic departments to memorise the taxis stops. Today, we neglect the significance of this national practice.

But finding loopholes and operating within them, while officials continued to contest your growth through fines, taking you into custody and closing more ranks to leave you homeless, was no longer enough. It was not sustainable. So, with the blessing of your loyal users and local store owners, a go-slow and barricading of major points was organised in 1988.

Your taxi family get-together, which we refer to as a taxi strike, was born. Law enforcement was brought in, drivers were arrested and soon after released with warnings.

For the first time since 1930, the government of the day decided to sit down with aboMalume noAuntie who operate you for civil negotiations. The outcome was the state agreeing that a limited number of permits would be granted and 16-seater taxis were legalised for public use.

How I wish my testimony to you ended without flaws. But news of black entrepreneurial opportunities made your family grow rapidly. The exponential growth brought about saturation, which created rivalry within the family, a rivalry that bred challenges with severe, irreversible consequences.

The rivalry was first catalysed by the government’s decision to issue a limited number of permits for black taxi operators so they could maintain some control over your family when 16-seater minibuses were legalised. Acquiring these limited permits from traffic departments was not pap en vleis and, because there were so many of you, many malumes and aunties who owned you decided to better their chances with bribery, hence the origin of the first sin in the Black, minibus taxi industry: corruption.

Then there was the matter of having too many taxis on the same route. To solve this, your family representatives had to negotiate and establish different routes for each owner’s fleet. Although this seemed fair, some routes had more commuters than others. So the more commuters a route had, the higher the intake, so the more sought-after the route was. The government was no longer the main obstacle. Instead, the cracks in the family dynamic began to show as each owner wanted what was best for them.

The family attempted to remedy this with the emergence of taxi associations, each of which represented (and continue to represent) the different owners’ interests and demands to other owners, government and law enforcement. This sparked the blood-shedding family feud between your owners, operators and various traffic departments, which you may know as the “taxi wars”, between 1977 and 2000.

The terms and conditions you were to be operated under resulted in the large, unrecorded number of deaths and injury of owners, drivers and commuters. The family members you lost are said to have been assassinated by rivals while commuters were unfortunate casualties. And, although I wish I only spoke of the past, such incidents continue today.

But it does not stop there. My dearest taxi, I cannot deny that my daily encounters with you trigger old and recent fears, fears of the perverted misogynist culture among the drivers who operate you, the not-so-queer-friendly ranks you call home, your disregard for road laws and the careless killings you are responsible for.

But knowing that you were forged as a defiant response by black entrepreneurs to apartheid policies has become the daily bread that nourishes me in the mornings, sustains me in the day and pacifies me in the night.

And when I forget, your melodious hooting expresses my ability to be heard in spaces where I was silenced. Your disregard for spaces reminds me to move freely. Your tireless trips to carry countless passengers to their destinations reminds me to extend a hand and never to measure my acts of botho/ubuntu as though there is a quota for good works.[22]

The Weeping of the “Rainbow Nation The Black Minibus Taxi Strike August 2023, in Western Cape, South Africa.

The residents in Cape Town throwing bottles at law enforcement officers amid a strike by Black taxi operators.

Photo Credit: Niamh Lynch Sky News reporter @niamhielynch

This week South Africa is still reeling from a massive taxi strike organised by the South African National Taxi Council, in Cape Town and surrounding areas due to unroadworthy taxis being impounded by road traffic authorities to combat the rising spectre of serious road traffic accidents. According to Mayor of Cape Town, Geordin Hill-Lewis[23], the SA National Taxi Alliance (Santaco) gained absolutely nothing from its strike across the Western Cape as on Thursday, 10 August, it ended up accepting the same deal it rejected eight days prior to that, when the taxi strike was called up by the Council. “The tragic implication is that all of the violence, the deplorable loss of life, and the damage to property and to our local economy all of it was for nought,” said Hill-Lewis after Santaco announced it would resume operations on Friday, 11th August 2023. The mayor shed some light on the agreement that the City of Cape Town and the Western Cape government reached with Santaco which led to the provincial taxi strike being called off. According to the deal, impoundments under the National Land Traffic Act (NLTA) will continue for vehicles driving without an operating licence, on the incorrect route, or without a driver’s licence, and for those that are not roadworthy. “We have agreed that the Taxi Task Team will further define a list, within 14 days, of additional major offences in terms of which vehicles will be impounded,” Hill-Lewis said. “This will take the form of a standard operating procedure (SOP) on the exercise of the discretionary power provided for in the National Land Transportation Act and would be similar to other SOPs which guide staff in respect to other laws and procedures.” The mayor said the city would focus on ensuring that traffic transgressions that affected commuter safety remained major offences. He said the Taxi Task Team would also compile an agreed-upon list of minor offences, which did not have commuter safety implications and that would not result in vehicles being impounded. “The city continues to believe it will be able to demonstrate to Santaco that we have already been following this distinction for some time,” Hill-Lewis said.[24] In addition, The City of Cape Town was most accommodating. “Importantly, if Santaco[25] believes that any of their taxis have been impounded for these minor offences, which we do not believe to be the case, then they can produce the relevant impoundment notices and we will make representations to the Public Prosecutor to support the release of these vehicles.” According to the mayor, Santaco agreed to never again call a strike during the middle of a working day and would always give at least 36 hours’ notice ahead of planned strike action. “We should never see a repeat of thousands of people being forced to walk home again,” he said, adding that the Taxi Task Team would now have a dispute resolution escalation and resolution clause. “These are the exact same conditions that Santaco needlessly rejected eight days ago. And not a single person gained anything from the violence that ensued. Instead, everyone lost, the commuters, taxi drivers and innocent residents of Cape Town,” Hill-Lewis said. The Peace disturbance, was profound. The violence and disruption disproportionately affected working-class commuters, but the unrest drew international attention this week, with Sky News [26]reporting that a British man holidaying in South Africa had been killed during the violence. Five deaths directly related to the strike were recorded. Sky News Headlines: “South Africa: British doctor among five people shot dead in unrest”. The 40-year-old victim, who was reportedly on holiday in the country, was killed while driving in the Ntlangano Crescent area, in a Black township of Cape Town. It is believed he had taken a wrong turn from a nearby Cape Town International Airport, while driving with two other people. A group then approached the vehicle and shot him. The nation is still weeping and so are the visitors.

However, the minibus taxi industry is a critical pillar of the public transport sector servicing the majority of South Africa’s working population. There have developed special business offering empowers “taxipreneurs”[27] while contributing to job creation and improving the safety of public transport in South Africa. These specialised businesses make a vital contribution to a market sector that has a stimulating effect on the national economy at many different levels.[28]

The taxi industry in South Africa, often referred to as the minibus taxi industry, is a substantial and important part of the country’s transportation sector and economy. It provides essential transportation services to millions of South Africans, particularly those in townships and informal settlements. The industry plays a crucial role in connecting people to jobs, schools, and various services, including, makeshift ambulances especially in cases of pregnant patients, in advanced stages of complicated labour, where these ladies need to be transported to public hospitals in cases of patients needing emergency caesarean sections, as observed by the author when he worked in the labour ward of King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban[29], where 26,0000 babies were delivered annually, with up to 60% by caesarean sections, due to cephalon-pelvic disproportion[30], [31], caused by malnourished mothers in childhood, under apartheid with them having larger babies as the economic status of the Black Africans improved in the past three decades, in South Africa, post liberation.

The worth or economic value of the taxi industry can be measured in various ways, including factors like annual revenue, employment generated, and its contribution to the broader economy. The taxi industry generates revenue through passenger fares and plays a role in the mobility of the workforce, thereby contributing to economic productivity.

The industry’s economic significance is not only in direct revenue but also in its indirect impact on various sectors. It supports vehicle manufacturing, fuel consumption, maintenance services, and other related businesses.

However, it’s important to note that the industry is complex, with many operators working as independent or small-scale businesses. This can make it challenging to quantify the industry’s total worth accurately. There are some 250 000 minibus taxis operating in South Africa, according to SA Taxi, the largest finance provider to the industry[32]. Some 69% of local households use minibus taxis. The industry generates annual revenues of an estimated R5 billion. The taxi industry transports majority of South Africa’s public commuters, but exact number of passengers remain unclear. In arguing that taxi drivers should be considered essential workers when Covid-19 vaccines are rolled out, the taxi industry claimed it transports 70% of South Africa’s commuters, or more than 15 million people daily.[33] The author has searched numerous official sites for reliable updated statistics regarding the minibus taxi industry in South Africa, but the figures vary since the entire industry is largely unregulated by government, with corruption at different levels of authority. However, The National Taxi Alliance did not provide a source for the statistic. Stats SA said it did not have an estimate of the total number of people who used taxis in a single day for any reason[34]. The statistics from their 2013 travel survey related only to workers using taxis as their main form of transport. The figure of 15 million has, however, been shared elsewhere.

SA Taxi, a taxi finance business[35], claims on its website that “taxi operators transport over 15 million commuters every day”. It attributes this figure to the national household travel survey, which does not appear to include the number. An SA Taxi spokesperson told Africa Check that the number came from a 2014 Reuters article which said the country’s taxi industry “moves 15 million people a day”. The author of the article told Africa Check that he couldn’t remember the exact source of the figure, but he thought it had been provided by an employee of the South African National Taxi Council. The council has not responded to requests for comment.

Number cited in report for national treasury A figure of “15 million taxi trips a day”, again attributed to SA Taxi, was included in a report for South Africa’s national treasury conducted by transport analyst Philip van Ryneveld. The report said the national household travel survey found that “in 2013 South Africa’s minibus taxis transported 6.26 million people in the morning”. Africa Check has tried to contact Van Ryneveld for clarity on how this figure was calculated. We have rated the claim that the taxi industry transports “more than 15 million commuters daily” as unproven. The figure does not appear to be supported by the available data. The figure will also vary depending on the definition of “commuter” used and if the number of people or individual taxi trips are counted.[36]

A study done by the Automobile Association of South Africa recorded an annual total of 70 000 minibus taxi crashes which indicates[37] that taxis in SA amount for double the rate of crashes than all other passenger vehicles.[38] Govender and Allopi has published an excellent reserch done on taxis in South Africa[39] Some information on the gross earnings on long trips made by taxi owner, ears as much as ZAR 37000 per month This is the reason that apart from taxis having a death toll of three South Africans, in taxi related motor vehicle accidents, per day, there are regular “Taxi Wars” [40]ongoing in the major cities in South Africa. Taxi bosses are gunned down by hit men arranged by the competition on a regular basis and crime prevention and arrests by law enforcement are non existent or protracted in legal cases where incompetent investigations are the norm, by law enforcement. The issue of “Taxi Wars” is based on territorial domains in South Africa. The term “Taxi Wars” refers to conflicts and disputes within the taxi industry in South Africa, often involving clashes between different taxi associations or groups over control of specific routes and territories. These conflicts have historically been driven by competition for passengers and the lucrative nature of certain routes.

The aetiology and factors resulting in these “Taxi Wars” are complex and compounded by the fact that law enforcement are helpless in the conflict, as the entire sage borders on intimidation, absence of witnesses and corruption. Some of the factors are:

Profitability: Certain routes are highly profitable due to passenger demand, and taxi operators may vie for control of these routes to secure their income.

Economic Factors: The taxi industry is a significant contributor to South Africa’s transportation sector and economy. As a result, operators are motivated to protect their interests and revenue streams.

Lack of Regulation: The taxi industry has historically faced challenges related to regulation and formalization. This has led to disputes over territory as different associations seek to establish control without clear regulatory oversight.

Competition and Rivalry: As the number of taxi operators has grown, competition for passengers has intensified, leading to conflicts over routes and territories.

Political Factors: Some conflicts within the taxi industry have been exacerbated by political influences, including attempts to gain support from certain groups or communities.

Safety Concerns: Taxi wars can have serious safety implications for passengers, bystanders, and operators themselves. Violence and intimidation are not uncommon in these disputes.

The taxi wars have a significant negative consequences, including:

Violence and Loss of Life: Conflicts over territorial domains have led to violence, injuries, and loss of life among taxi operators, passengers, and bystanders.

Disruption of Services: Taxi wars disrupt transportation services, affecting commuters who rely on taxis for daily travel.

Economic Impact: The conflicts can lead to financial losses for operators, as well as damage to vehicles and infrastructure.

Law Enforcement Challenges: Policing and regulating taxi wars pose challenges for law enforcement agencies.

The South African government has taken steps to address the challenges within the taxi industry, including efforts to formalize and regulate the industry, improve safety standards, and mediate conflicts between taxi associations. This peace disruption requires a combination of regulatory measures, focused law enforcement efforts, community engagement, and dialogue among industry stakeholders.

There have been instances and allegations of taxi associations or leaders exerting influence in certain municipalities in South Africa. These situations are often characterised by a complex interplay of economic interests, political dynamics, corruption and governance challenges. However, it’s important to note that the extent to which taxi bosses “rule” municipalities can vary widely and may not be universally applicable to all municipalities.

Some key points to consider:

Local Influence: In some cases, powerful taxi associations or individuals within the taxi industry have been reported to exert influence at the local level, including within certain municipalities. This influence may be related to political support, economic interests, or control over transportation routes.

Political Dynamics: The taxi industry’s significant presence in South Africa, coupled with its ability to mobilize support, has led to intersections with local politics. Some taxi associations have endorsed political parties or candidates and may seek influence in return.

Economic Factors: The taxi industry is an important economic contributor, and taxi operators often hold considerable economic power. This economic strength can translate into influence over local matters, especially in areas where formal governance structures may be weaker.

Regulation and Informal Governance: The taxi industry has historically operated within a regulatory grey area, leading to informal governance structures emerging. In some cases, taxi associations have taken on roles that extend beyond transportation, potentially affecting local dynamics.

Varied Regional Impact: The degree of influence that taxi bosses may have over municipalities can vary significantly from one region to another. Factors such as the strength of local institutions, the presence of other power centres, and the relationship between taxi associations and local government officials all play a role.

Efforts for Regulation: The South African government has taken steps to regulate the taxi industry more comprehensively. This includes efforts to formalize the industry, improve safety standards, and ensure proper governance.

South Africa’s taxi industry is organised into various associations[41] and bodies, each representing different segments of the industry. The situation is dynamic and continuously evolving, due to assassinations of individuals and gangsterism. Some of the prominent taxi bodies and associations in South Africa are:

South African National Taxi Council (SANTACO): SANTACO is one of the most significant and recognizable taxi associations in the country. It aims to represent the interests of taxi operators and promote the growth and development of the industry. SANTACO has regional structures across South Africa.

National Taxi Alliance (NTA): NTA is another influential taxi association that represents the interests of taxi operators. It has been involved in advocating for the industry’s interests and engaging with government authorities.

South African National Taxi Association (SANTA): SANTA is an organization that focuses on promoting the interests of the taxi industry, including issues related to regulations, policies, and transformation.

Cape Amalgamated Taxi Association (CATA): CATA is a prominent taxi association operating in the Western Cape province. It represents taxi operators in the Cape Town metropolitan area.

Gauteng Provincial Taxi Council (GPTC): GPTC represents taxi operators in the Gauteng province, which includes Johannesburg and Pretoria. It focuses on advocating for the interests of taxi operators in the region.

KwaZulu-Natal Taxi Council (KZNTC): KZNTC represents taxi operators in the KwaZulu-Natal province and is involved in issues affecting the taxi industry in the region.

Eastern Cape Transport Association (ECTA): ECTA is an association that represents taxi operators in the Eastern Cape province. It addresses issues related to the taxi industry in the region.

Mpumalanga United Taxi Association (MUTA): MUTA is an association that represents taxi operators in the Mpumalanga province.

Main Photo: A serious Minibus Taxi Accident with bodies covered along the roadside in the Province of Mpumalanga in South Africa. Note the large mortuary vehicle to transport the bodies of the victims. Often, entire family is decimated, in a single taxi accident, along national freeways.

Inset: A Minibus Taxi accident, in South Africa on a “Long Haul” trip, with reckless driving and driver fatigue resulting is multiple fatalities and serious morbidities, amongst the survivors.

The Black taxi industry is highly decentralised, with numerous regional and local associations representing the interests of taxi operators in specific areas. The complexity of the industry and its relationships with various government authorities, regulatory bodies, and communities contribute to the presence of multiple taxi bodies.

In order to increase incomes from the number of trips made per day, the taxi drivers resort to some desperate measures. There are reports of drug abuse amongst the frivers. The idea of using marijuana (cannabis) to enhance performance, such as driving fast and completing more trips in a short time, is both dangerous and illegal. Driving under the influence of any substance that impairs cognitive and motor functions, including marijuana, is a serious safety risk and is against the law in most jurisdictions.

The important points to consider, and these are some causative factors to account for the inordinately high numbers of accidents involving Black owned, minibus taxis, in South Africa:

Impaired Driving: Marijuana use can impair cognitive functions, coordination, and reaction times, all of which are crucial for safe driving. Impaired driving increases the risk of accidents, injuries, and fatalities for the driver, passengers, and others on the road.

Legal Consequences: Driving under the influence of marijuana is illegal in many places. Penalties for impaired driving can include fines, license suspension, imprisonment, and other legal consequences. However, the law enforcement is powerless in this arena.

Safety of Passengers and Others: Passengers, pedestrians, and other drivers are all put at risk when a driver is impaired. It’s the responsibility of a driver to ensure the safety of themselves and all others on the road.

Ethical Considerations: Encouraging or endorsing the use of substances to enhance driving performance is ethically questionable and can have serious consequences for public safety.

Alternative Solutions: If taxi drivers are looking to increase their income, it’s important to focus on safe and responsible driving practices, adherence to traffic laws, and providing quality service to passengers.

Public Perception: Promoting or engaging in unsafe behaviour can negatively impact the reputation of the taxi industry and undermine the trust that passengers have in taxi services.

Ultimately, safety should always be the top priority for all road users, including taxi drivers. It’s important to comply with traffic laws, avoid any form of impaired driving, and prioritise the well-being of oneself and others. If there are concerns about income, exploring legitimate ways to improve service quality and efficiency, rather than resorting to unsafe practices, is the responsible approach.

All readers are kindly requested to access this YouTube video link, courtesy of news 24: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBEJpGDKmo4 to see the shocking behaviour of a reckless taxi driver, hurtling down the Fields Hill in KwaZulu-Natal [42]in heavy rain, in the wrong lane. Fields Hill is notorious for accidents, even under, daylight, normal conditions and visibility, but, in heavy rain the statistics for serious and often fatal accidents, increase exponentially. The readers can then appreciate the gravity and extent of the lawlessness and anarchy, brazenly demonstrated by minibus taxi drivers, on the national roads in South Africa, causing Peace Disruption as the nation to continues to weep.

Main Picture: A horrific accident between a bakkie and a minibus taxi, involved in a head-on collision, due to overtaking on a blind rise, with mangled bodies strewn along the roadside. Can any mortal survive this carnage of two machines driving recklessly at high speeds?

Inset: A new “Toyota, Hiace” Minibus Taxis: the 15 Seater Mass Black Transport system in South Africa, Manufactured in the Toyota plant in Prospecton, Kwa Zulu Natal south of Durban.

Since all the minibus taxis are Toyotas, like many automotive manufacturers, the Japanese company places a strong emphasis on safety and has various corporate responsibility programmes aimed at promoting road safety and vehicle safety. These initiatives often include a combination of research, technology development, education, and collaboration with various stakeholders.

Vehicle Safety Features: Toyota continually invests in research and development to incorporate advanced safety features into their vehicles. These features can include collision avoidance systems, airbags, stability control, lane departure warning, and more.

Safety Research and Innovation: Toyota is involved in research to improve vehicle safety and develop new safety technologies. This research contributes to the development of safer vehicles and driving practices.

Educational Campaigns: Many automotive companies, including Toyota, engage in educational campaigns to raise awareness about safe driving practices and the importance of using safety features. These campaigns often target both drivers and passengers.

Partnerships: Toyota collaborates with government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and other stakeholders to promote road safety. These partnerships often involve sharing data, expertise, and resources to improve road safety on a broader scale.

Vehicle Recalls and Maintenance: Toyota takes responsibility for ensuring that its vehicles are safe on the road. If any safety-related defects are identified, the company initiates recalls to address these issues and maintain the safety of its vehicles.

Community Engagement: Toyota may engage with communities to promote safe driving behaviours and provide resources for road safety education

While vehicle manufacturers like Toyota play a significant role in promoting safety through their vehicles and initiatives, road safety is a shared responsibility that involves multiple stakeholders working together, in a cohesive manner.

The origin of “kombi taxis” in South Africa can be traced back to the era of apartheid, specifically during the 1970s and 1980s. These vehicles, known as “kombis” or “minibuses,” were initially introduced as an informal and alternative means of transportation due to the lack of reliable public transportation options for the majority of South Africans, especially those in townships and informal settlements.

Noting that Minibus Taxis were only legalised in 1987, it is relevant to present an overview of their origins and development:

Apartheid-Era Transportation: During apartheid, the South African government implemented policies that segregated different racial groups, and this segregation extended to transportation systems. Public transportation was often inadequate and segregated, with black communities receiving subpar services.

Emergence of Informal Transport: In response to the limited transportation options, individuals started converting vans into makeshift minibuses, known as “kombis,” to transport people within townships and between urban areas. These vehicles provided a more flexible and accessible option for people who needed to travel but were underserved by formal transportation.

Unregulated Industry: The kombi taxi industry initially emerged as an unregulated and informal form of transportation. The lack of formal regulations led to challenges related to safety, fare consistency, and competition for passengers.

Popularity and Growth: Despite the lack of regulation, the kombi taxi industry gained popularity due to its accessibility and affordability compared to other transportation options. As the demand for these services grew, more operators entered the industry, leading to increased competition.

Regulation Attempts: In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as apartheid started to come to an end, there were efforts to regulate the informal taxi industry. Formal regulations were introduced to address safety concerns, fare structures, and routes. However, implementing these regulations proved to be a complex process due to the industry’s scale and complexity.

Transformation Post-Apartheid: With the transition to democracy in the 1990s, the taxi industry underwent a transformation. The introduction of formal regulations aimed to improve safety, standardize fare structures, and create a more organised industry.

Today, the taxi industry in South Africa remains a crucial part of the country’s transportation landscape, particularly for individuals living in townships and informal settlements. While there have been efforts to regulate and formalise the industry, challenges related to safety, competition, and infrastructure persist.

The issue of tax compliance within the taxi industry [43]can vary widely and is influenced by several factors, including the regulatory environment, the structure of the industry, and individual operator behaviour, it is prudent to present general insights into the tax compliance situation within the taxi industry in South Africa.

Formalisation Efforts: In recent years, there have been efforts to formalise the taxi industry in South Africa, including measures to improve tax compliance. Some taxi operators have registered their businesses and have been working toward complying with tax regulations.

Informal Nature: However, the taxi industry historically had informal aspects, including operators who may have been less inclined to formalize their businesses and adhere to tax obligations. The industry’s informal nature has sometimes made it challenging for tax authorities to ensure compliance across the board.

Varying Compliance Levels: Compliance levels within the taxi industry can vary. Some operators may diligently fulfil their tax obligations, while others may not. Factors influencing compliance can include awareness of tax requirements, the structure of the business, access to financial education, and regulatory enforcement.

Regulatory Changes: Regulatory changes aimed at improving tax compliance and formalizing the industry can influence the behaviour of taxi operators. Clearer regulations and enforcement mechanisms can encourage greater compliance.

Challenges and Solutions: Challenges related to tracking cash transactions and the fluid nature of the industry can contribute to compliance difficulties. Introducing digital payment methods, proper record-keeping practices, and financial education can help improve compliance.

Tax authorities, such as the South African Revenue Service (SARS), are responsible for enforcing tax regulations across all sectors, including the taxi industry. They implement measures to ensure that businesses, including taxi operators, fulfil their tax obligations.

It is important to emphasize that making sweeping generalisations about the entire taxi industry is not accurate. There are certainly taxi operators who are compliant with tax regulations, and there are ongoing efforts to improve overall compliance within the industry.

Most South African are of the opinion that the government should review the minibus taxi mass commuter transport system, noting the inordinately high level of serious, often fatal, traffic accidents, resulting in morbidity and mortality, costing South Africa, the lives of their loved ones, needless to mention the billions drained in medical treatment and on the economy. Taxis and underground metro systems can indeed coexist and often do in many cities around the world. Both modes of transportation serve different purposes and can complement each other within a comprehensive urban transportation network. The coexistence of taxis and underground metros can be seen in various countries and cities. Here are a few examples:

London, United Kingdom: London is a classic example of a city where taxis (black cabs) and the London Underground (Tube) coexist. Taxis are often used for point-to-point travel or when specific routes are not covered by the Tube. The London Underground, on the other hand, provides a fast and efficient way to move across the city.

New York City, United States: In New York City, taxis (yellow cabs) are iconic and widely used for on-demand transportation. The city also has an extensive subway system that provides efficient mass transit, especially for longer distances or during rush hours.

Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo’s highly efficient metro system is complemented by an extensive network of taxis. Taxis in Tokyo provide convenient transportation to and from stations, as well as to destinations not directly accessible by metro.

Paris, France: The Paris Métro is a well-known example of an underground metro system. Taxis in Paris serve both locals and tourists, offering flexible transportation options beyond the metro’s coverage.

Seoul, South Korea: Seoul’s extensive metro system is supported by a network of taxis that offer convenience and accessibility, especially for locations not directly served by the metro lines.

Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong’s well-developed metro system is integrated with other modes of transportation, including taxis, to provide seamless connectivity.

In these examples, taxis and underground metro systems coexist by fulfilling different transportation needs:

Taxis offer door-to-door service, flexibility in route choice, and convenience for travel to destinations not directly accessible by the metro.

Underground metros provide efficient, high-capacity transportation for longer distances and along fixed routes, especially during peak hours.

The coexistence of taxis and underground metros is a testament to the importance of having a diverse and comprehensive transportation network in urban areas. It allows residents and visitors to choose the mode of transportation that best suits their needs for a particular trip. Successful coexistence often depends on effective integration, reliable scheduling, clear signage, and proper urban planning. possible for taxis and an underground metro system to coexist in South Africa. The coexistence of these modes of transportation would depend on several factors, including urban planning, transportation policies, infrastructure development, and public preferences. While there might be challenges, successful coexistence is achievable with careful planning and coordination. Some considerations are:

Complementary Roles: Taxis and an underground metro system can play complementary roles in an urban transportation network. Taxis can provide flexible, last-mile connectivity to and from metro stations, reaching areas not covered by the metro.

Demand and Coverage: Evaluate the demand for public transportation and identify areas where an underground metro system would be most effective. The metro could serve high-density corridors with heavy traffic, while taxis could provide access to neighborhoods beyond the metro’s reach.

Integrated Planning: Urban planning should focus on integrating different modes of transportation, including taxis and the metro. Stations, stops, and routes should be designed to allow seamless transfers between modes.

Accessibility and Affordability: Consider the needs of various socio-economic groups. Taxis might offer affordability and accessibility advantages to certain populations, while the metro could provide a cost-effective option for longer commutes.

Infrastructure Investment: Developing an underground metro system requires significant investment in infrastructure, construction, and technology. Funding sources and feasibility studies are crucial considerations.

Regulation and Licensing: Clear regulations and licensing processes for taxis should be established to ensure safety, fare consistency, and quality service.

Public Awareness and Education: Educating the public about the benefits and proper use of both modes is important for successful coexistence.

Government Support: Government support in terms of policy, funding, and regulatory framework will be essential for the development of both systems.

Community Engagement: Engage communities and stakeholders to address concerns and incorporate local input in the planning process.

Successful coexistence would require a comprehensive and integrated approach to transportation planning. It’s important to learn from the experiences of other cities that have implemented similar systems, adapt strategies to the local context, and address challenges specific to South Africa.

While establishing an underground metro system is a complex and long-term endeavour, it can be a transformative investment for a city’s mobility and economic growth. When combined with an existing taxi network, the result could be a more efficient, accessible, and sustainable transportation landscape.

The greatest danger to South Africans from taxis primarily relates to road safety issues. While taxis are an essential mode of transportation for many people in South Africa, there have been concerns and challenges related to road safety within the taxi industry. Some of the dangers associated with taxis include:

Traffic Accidents: One of the most significant dangers is the occurrence of traffic accidents involving taxis. Factors such as speeding, reckless driving, overloading, inadequate vehicle maintenance, and aggressive driving behaviours can contribute to a higher risk of accidents.

Overloading: Many taxis are known to be overloaded, carrying more passengers than their legal capacity. Overloading can affect the stability and handling of the vehicle, increasing the likelihood of accidents and injuries.

Unsafe Driving Practices: Some taxi drivers might engage in unsafe driving practices, including running red lights, not obeying traffic rules, and disregarding road signs. These behaviours can lead to accidents and endanger other road users.

Inadequate Vehicle Maintenance: Due to financial constraints or lack of proper regulations, some taxis might not receive regular maintenance, leading to mechanical failures that can result in accidents.

Driver Fatigue: Taxi drivers often work long hours to maximize their earnings, which can lead to driver fatigue. Fatigued drivers are more prone to making errors and experiencing reduced reaction times.

Lack of Seat Belts: In some cases, taxis might not be equipped with proper seat belts for all passengers, increasing the risk of injuries in the event of an accident.

Road Infrastructure Challenges: Poor road infrastructure, inadequate signage, and road maintenance issues can contribute to accidents involving taxis.

Aggressive Competition: Competition among taxi operators for passengers can lead to aggressive driving behaviours and unsafe practices on the road.

It is important to note that while these dangers exist within the taxi industry, they are not representative of all taxi operators. There are responsible and safety-conscious taxi drivers who prioritize the well-being of their passengers and other road users. To address these dangers, it’s crucial to focus on improving road safety standards, enforcing traffic regulations, implementing regular vehicle inspections, and promoting safe driving behaviors among all road users, including taxi drivers

One of the greatest threats to the black taxi industry in South Africa is the need for modernization and adaptation in the face of changing transportation trends, technologies, and regulatory environments. While the taxi industry remains a vital mode of transportation for many South Africans, several challenges and threats need to be addressed for its continued sustainability:

Competition from Ridesharing Services: The emergence of ridesharing platforms like Uber and Bolt has introduced new competition to the traditional taxi industry. These services offer convenience and often operate using modern technology, which can attract passengers away from traditional taxis.

Regulation and Formalization: The informal nature of the taxi industry in South Africa has posed challenges in terms of regulation, safety standards, and formalization. There is a growing need for the industry to meet modern regulatory requirements to ensure passenger safety and quality service.

Infrastructure and Technology: Many taxi operations lack modern technologies for booking, navigation, and communication. Adapting to new technologies can enhance efficiency and improve the passenger experience.

Road Safety and Reputation: Addressing road safety issues and improving the reputation of the industry in terms of safe driving practices and passenger safety is essential for its credibility and success.

Public Perception: The industry’s reputation and perception among the public can impact its success. Efforts are needed to address negative perceptions and ensure that taxis are seen as a safe and reliable mode of transportation.

Urbanization and Traffic Congestion: Rapid urbanization and traffic congestion in major cities can affect the efficiency and reliability of taxi services. Solutions are needed to navigate congested urban environments effectively.

Environmental Concerns: With increasing concerns about environmental sustainability, there is a need for the taxi industry to consider cleaner and more energy-efficient vehicles.

Driver Welfare and Working Conditions: Ensuring fair working conditions, driver welfare, and professional development opportunities are important for retaining skilled drivers and improving overall service quality.

Integration with Public Transportation: Integrating taxis more effectively into broader public transportation networks can improve overall mobility options for citizens.

Economic Challenges: Economic pressures and fluctuating fuel prices can impact the affordability and viability of taxi services.

Addressing these challenges requires collaboration among taxi associations, government agencies, and relevant stakeholders. By embracing modernization, technology, safety measures, and customer service improvements, the black taxi industry can adapt to the changing landscape and continue to provide essential transportation services to all South Africans, of all races, as presently, these taxis are predominantly used by Black commuters, avoided by other races, mainly for security and safety reasons.

In terms of modernisation of the industry, taxi associations in South Africa have the potential to adopt electric or hybrid vehicles in the future as part of efforts to update their fleets and contribute to environmental sustainability. The shift toward electric or hybrid vehicles can offer several benefits to the taxi industry, passengers, and the environment. Here are some considerations:

Environmental Impact: Electric and hybrid vehicles produce fewer emissions compared to traditional internal combustion engine vehicles. They contribute to reducing air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, which is crucial for environmental and public health.

Operating Costs: Electric vehicles (EVs) have lower operating and maintenance costs compared to vehicles powered by fossil fuels. Electricity is generally more affordable than gasoline or diesel fuel, and EVs have fewer moving parts that require maintenance.

Fuel Savings: EVs and hybrids are more energy-efficient, allowing taxi operators to save on fuel costs over time. This can be especially advantageous given the potential volatility of fuel prices.

Quiet Operation: Electric vehicles operate quietly, reducing noise pollution in urban areas and enhancing the passenger experience.

Incentives: Some governments offer incentives and subsidies for purchasing electric or hybrid vehicles, which can help offset the initial higher cost of these vehicles.

Improved Reputation: Operating eco-friendly vehicles can improve the reputation of taxi operators and associations, attracting environmentally conscious passengers.

Considerations and Challenges:

Infrastructure: The availability of charging infrastructure is crucial for the successful adoption of electric vehicles. Taxi associations would need to work with relevant authorities to ensure convenient and accessible charging points.

Initial Costs: Electric vehicles can have a higher upfront cost compared to conventional vehicles. However, lower operating and maintenance costs can help offset this initial investment over time.

Range and Charging Time: While the range of electric vehicles is improving, it’s important to consider the daily operational needs of taxis. Ensuring sufficient range and minimizing downtime for charging is essential.

Vehicle Options: Availability of electric or hybrid vehicles suitable for taxi operations might vary. Taxi associations would need to research and choose vehicles that meet their specific needs.

Education and Training: Drivers and operators may require training to adapt to electric or hybrid vehicle technology and charging practices.

Infrastructure Investment: Transitioning to electric or hybrid vehicles may require initial investment in charging infrastructure, vehicle purchases, and training.

The adoption of electric or hybrid vehicles in the taxi industry aligns with global trends toward sustainable transportation and can contribute to reducing the industry’s environmental footprint. Taxi associations, in collaboration with government agencies, vehicle manufacturers, and other stakeholders, can work to overcome challenges and promote the transition to cleaner and more efficient vehicle

Furthermore, while it is theoretically possible for the global oil industry to influence or set up impediments to the transformation of Black taxis (or any vehicles) to electric vehicles (EVs), there are several factors to consider:

Market Dynamics: The transition to EVs is driven by a combination of factors, including environmental concerns, technological advancements, government policies, consumer demand, and economic considerations. These factors collectively shape the shift toward cleaner transportation.

Competing Interests: While the oil industry might have a stake in maintaining fossil fuel consumption, the automotive industry is also evolving to meet the demands for cleaner and more sustainable transportation. Many major car manufacturers are investing heavily in EV technologies, suggesting a broader shift that can’t be entirely controlled by the oil industry.

Consumer Demand: Increasing awareness and concern about climate change and pollution have led to growing consumer interest in electric vehicles. Consumers are seeking alternatives to traditional fossil fuel-powered vehicles due to both environmental and economic reasons.

Government Policies: Many governments around the world are implementing policies and incentives to encourage the adoption of electric vehicles. These policies often include subsidies, tax benefits, and regulations that favor EVs. Government support can override potential impediments from the oil industry.

Global Movement: The transition to electric vehicles is a global movement supported by multiple stakeholders, including governments, environmental organizations, consumers, and industries. This collective effort makes it challenging for any single entity to completely impede progress.

Technological Advancements: Rapid advancements in battery technology and charging infrastructure have made electric vehicles more practical and attractive to consumers. These advancements have reduced range anxiety and increased the convenience of EV ownership.

Diversification by Oil Companies: Some oil companies are diversifying their portfolios to include renewable energy sources, recognising the evolving energy landscape. This suggests that even within the oil industry, there’s acknowledgment of the need to adapt to changing market dynamics.

While there might be potential challenges and resistance, the broader shift toward electric vehicles is driven by a complex interplay of economic, technological, environmental, and social factors. The transportation industry is undergoing a transformation that involves various stakeholders beyond just the oil industry. As a result, the transformation of Black taxis or any vehicles to electric vehicles is influenced by a multitude of forces that extend beyond the control of a single industry.

While electric or hybrid taxis offer several advantages, there are also potential disadvantages and challenges associated with their adoption for mass transport in South Africa. It’s important to consider these factors when evaluating the feasibility and impact of transitioning to electric or hybrid taxis:

Initial Cost: Electric and hybrid vehicles tend to have higher upfront costs compared to traditional internal combustion engine vehicles. The initial investment for purchasing these vehicles can be a barrier, especially for taxi operators who may already face financial constraints.

Charging Infrastructure: Establishing a robust and accessible charging infrastructure is crucial for electric vehicles. Developing an extensive network of charging stations requires significant investment and planning. In areas with limited charging infrastructure, range anxiety could be a concern for taxi drivers.

Range Limitations: Electric vehicles have a limited driving range compared to traditional vehicles with internal combustion engines. For taxis that cover longer distances or operate continuously, managing the range and charging logistics can be challenging.

Charging Time: While charging technology is improving, the time required to fully charge an electric vehicle is still longer than refueling a conventional vehicle with gasoline or diesel. Long charging times can result in downtime for taxi operators.

Battery Life and Replacement Costs: Electric vehicle batteries degrade over time, impacting their driving range and performance. Replacing a battery can be expensive, and taxi operators need to consider the long-term maintenance and replacement costs.

Load-Carrying Capacity: Electric vehicles’ weight due to battery packs might impact load-carrying capacity. Taxis that need to accommodate multiple passengers and luggage might face limitations.

Driving Conditions: Electric vehicles’ performance can be affected by extreme weather conditions, such as very high or low temperatures. This can impact battery efficiency and overall driving experience.

Infrastructure Challenges: Some areas in South Africa might lack the necessary electrical infrastructure to support a large-scale deployment of electric vehicles. Upgrading infrastructure to accommodate increased electricity demand could be a significant undertaking.

Technological Familiarity: Taxi drivers and operators might need training and education to adapt to electric vehicle technology, including charging procedures and maintenance practices.

Resale Value: The resale value of electric vehicles can be uncertain due to rapid advancements in technology and concerns about battery life. Taxi operators need to carefully consider the long-term value of their investments.

Environmental Considerations: While electric vehicles produce fewer tailpipe emissions, the environmental benefits depend on the source of electricity generation. In regions where electricity is primarily derived from coal, the net environmental impact might be reduced.

Overall, the decision to adopt electric or hybrid taxis for mass transport[44] should be based on a thorough assessment of the local context, infrastructure availability, financial considerations, and regulatory support. As technology continues to evolve and charging infrastructure expands, some of these challenges may become less significant over a period of time.

The Bottom Line is that the South African, Black minibus taxi industry originated as an indefatigable symbol of defiance against the former apartheid government, which had used the Public Utility Transport Corporation (PUTCO) to generate revenues for the state by forced removals of South Africa Blacks far away from their places of employment in terms of the Group Areas Act, to sprawling townships. These PUTCO buses formed the initial mass transportation system for Blacks in South Africa. There is a long history related to these “Black Buses”, which is beyond the scope of this publication, but suffice to say that it inspired the origins of the Black Minibus Taxi industry. [45]

Furthermore, during the two focus group interviews, minibus taxi drivers identified challenges they are encountering in regards to their working conditions, perspective on advanced driving, and their behaviour towards other road users and law enforcement. From the thematic analysis of the focus group interviews, four themes emerged: law enforcement is against minibus taxi drivers’ perspective; other road users lack respect for minibus taxi drivers; poor working conditions with a lack of incentives; and aggressive driving.[46]

Other aspects of this concerns the modernisation of the taxi industry in South Africa, including use of electric or hybrid taxis.

In the following parts of this series on “South Africa is still Weeping”, the author will delve further into the multifaceted layers and causes of South Africa’s weeping, examining the socio-political structure of the fabric of the South African taxi tapestry, as well as other challenges, which makes the nation weep, post liberation.

There is hope in the ongoing weeping and the tears will dry out, as South Africa, Sandton City[47], north of Johannesburg[48], is gearing up for the BRICS Summit, South Africa 2023[49], next week, with Brazil, Russia, India and China. Needless to note that President Putin [50]will be participating in the summit, on-line in view of the arrest warrant issued, against him by the International Criminal Court, for alleged crimes against humanity in the Ukraine War[51].

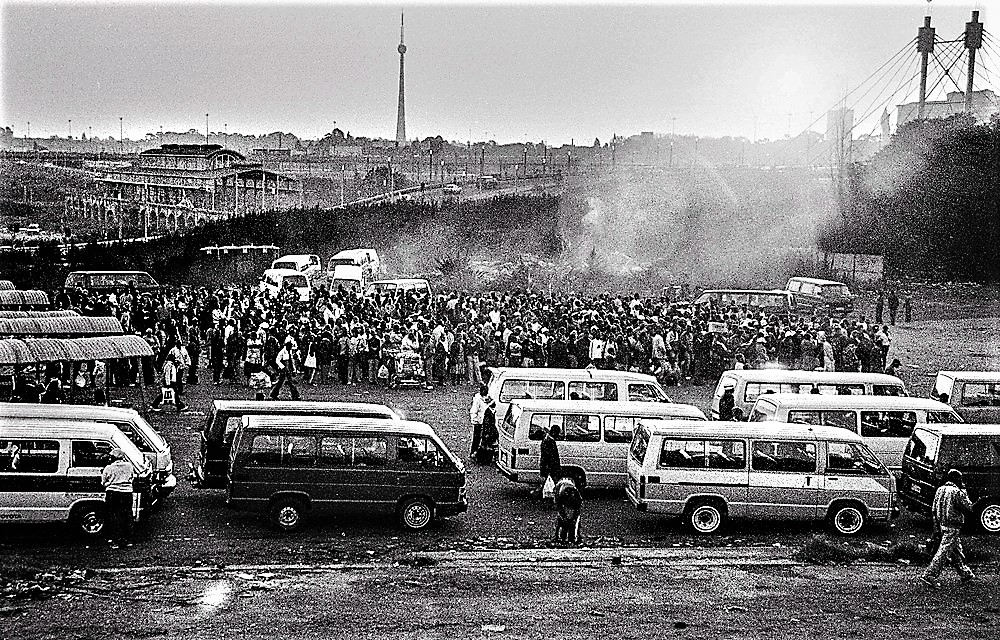

The Long Journey: The busy Bree Street Black, Minibus taxi rank in Central Johannesburg, South Africa, with the numerous “Coffins on Wheels” waiting to load the commuters, for some of whom it will be their final journey and destination.

References:

[1] Personal quote by author August 2023

[2] https://www.toyota.co.za/ranges/hiace-sesfikile

[3] Phrase first coined by the author in 2022

[4] https://mg.co.za/article/2018-04-20-00-the-indefatigable-taxi-is-asymbol-of-defiance/

[5] https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201505/act-44-1948.pdf

[6] https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6741479M/Report_of_the_Road_motor_competition_commission.

[7] https://www.news24.com/life/Arts-and-entertainment/Arts/after-robot-how-taxis-became-the-mobility-sterrings-of-the-road-20201007

[8] https://www.bridgetaxifinance.co.za/taxi-the-60s-and-70s/

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PUTCO

[10] https://www.bing.com/search?q=alexandra%2c+south+africa&filters=dtbk:%22MCFvdmVydmlldyFvdmVydmlldyFmNTgzNTllMi05NzU2LTM0NTUtMzBmYy1hNjAzYTI4MjhhY2I%3d%22+sid:%22f58359e2-9756-3455-30fc-a603a2828acb%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[11] https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/popular-struggles-early-years-apartheid-1948-1960

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammanskraal

[13] https://www.bing.com/search?q=pretoria&filters=dtbk:%22MCFvdmVydmlldyFvdmVydmlldyEzZmE0M2NjYS0zNDA5LTRkODEtZjRmOS0yZGY3NGUzN2UxNzc%3d%22+sid:%223fa43cca-3409-4d81-f4f9-2df74e37e177%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_sanctions_during_apartheid

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toyota_HiAce

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxi_wars_in_South_Africa

[17] https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/35528gen575.pdf

[18] https://www.gov.za/documents/road-transportation-act-16-apr-2015-0812

[19] https://www.wordsworth.co.za/products/dont-upset-oomalume

[20] https://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/james-filbert-sojane-sports-administrator-and-pioneer-taxi-industry-dies

[21] https://vymaps.com/ZA/Pat-Mbatha-Bus-Taxi-Way-548376/

[22] https://mg.co.za/article/2018-04-20-00-the-indefatigable-taxi-is-asymbol-of-defiance/#:~:text=But%20it%20does,for%20good%20works.

[23] https://www.bing.com/news/search?q=Mayor+Of+Cape+Town%2c+Geordin+Hill-Lewis&qpvt=Mayor+of+Cape+Town%2c+Geordin+Hill-Lewis&FORM=EWRE

[24] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-08-11-santaco-gained-nothing-from-taxi-strike-instead-everyone-lost-mainly-the-poor-says-cape-town-mayor/

[26] https://news.sky.com/story/south-africa-british-doctor-among-five-people-shot-dead-in-unrest-12936806

[28] https://safacts.co.za/taxi-services-in-south-africa/

[29] https://www.kznhealth.gov.za/kingedwardhospital.htm

[30] https://www.who.int/news/item/16-06-2021-caesarean-section-rates-continue-to-rise-amid-growing-inequalities-in-access

[31] https://www.who.int/news/item/16-06-2021-caesarean-section-rates-continue-to-rise-amid-growing-inequalities-in-access

[32] https://www.transport.gov.za/documents/11623/189609/regulation_discussion_Sep2020.pdf/786c1d7f-65e3-4932-8563-0415d27b8b99

[33] https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/reports/taxi-industry-transports-majority-south-africas-public-commuters-exact-number

[34] https://www.polity.org.za/print-version/taxi-industry-transports-majority-of-south-africas-public-commuters-but-exact-number-of-passengers-unclear-2021-02-03#:~:text=Stats%20SA%20said%20it%20did%20not%20have%20an,figure%20of%2015-million%20has%2C%20however%2C%20been%20shared%20elsewhere.

[35] https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/companies/transport-and-tourism/2020-04-23-sa-taxi-signs-loan-deal-of-r19bn-with-african-development-bank/#:~:text=SA%20Taxi%20is%20a%20subsidiary%20of%20JSE-listed%20group,ordinarily%20qualify%20for%20the%20formal%20banking%20sector%20services.

[36] https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/reports/taxi-industry-transports-majority-south-africas-public-commuters-exact-number#:~:text=The%20National%20Taxi%20Alliance%20did,individual%20taxi%20trips%20are%20counted.

[37] https://www.arrivealive.co.za/minibus-taxis-and-road-safety

[38] https://www.google.com/search?sca_esv=557985309&rlz=1C1YTUH_enZA1040ZA1040&q=how+many+taxi+accidents+in+south+africa&spell=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj5i5jjlOWAAxXWUkEAHdGeBY0QBSgAegQICBAB&biw=1280&bih=603&dpr=1.5

[39] https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/6052/022.pdf?sequence=1

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_Cape_Town_taxi_conflict#:~:text=The%202021%20Cape%20Town%20taxi%20conflict%20was%20a,lucrative%20taxi%20routes%20in%20Cape%20Town%2C%20South%20Africa.

[41] https://safacts.co.za/list-of-taxi-association-in-south-africa/#:~:text=Vuwani%20Taxi%20Association.%20Ficksburg%20Taxi%20Association.%20Federated%20Taxi,District%20Taxi%20Assn.%20South%20Africa%20National%20Taxi%20Council.

[42] https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/fields-hill-report-warned-of-tragedy-1575147

[43] https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/489507/sars-is-going-after-taxis-in-its-next-tax-drive-in-south-africa/

[44] https://topauto.co.za/features/81692/electric-taxis-for-south-africa-this-is-the-plan/

[45] https://mg.co.za/author/zaza-hlalethwa/

[46] https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/87381/2D_02.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[48] https://joburg.co.za/explore-johannesburg-north/#:~:text=Johannesburg%20North%20comprises%20of%20Sandton%2C%20Bryanston%2C%20Rosebank%2C%20Melville%2C,a%20look%20at%20our%20guide%20to%20the%20area.

[49] https://www.bing.com/news/search?q=Brics+Summit+South+Africa+2023&qpvt=brics+summit+south+africa+2023&FORM=EWRE

[50] https://www.bing.com/news/search?q=President+Putin&qpvt=president+putin+latest+news&FORM=EWRE

[51] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-64992727

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: South Africa

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 21 Aug 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: South Africa, My Birthplace, Still Weeping: Coffin on Wheels (Part 2), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.