Exploring the Centrality of Nonviolent Communication for Resolution of Conflicts and a Culture of Peace

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 11 Sep 2023

Vedabhyas Kundu | CIC-Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

At a time when humanity finds itself enveloped by conflicts of different kinds, violence, greed and crimes at various levels, the world hungers for peace and nonviolence. The United Nations talks about how conflict and violence ‘are currently on the rise’. It talks of the rising involvement of non-state actors like political militias, criminal and international terrorist groups. Amongst the dominant forces behind conflicts according to the United Nations are unresolved regional tensions, breakdown in the rule of law, absent or co-opted state institutions, illicit economic gain and the scarcity of resources. The aim is to constantly work to find frameworks and practical models to end these conflicts. The challenge is not just to find solutions for cessation of these conflicts but also to address the root cause of these violence. In most of these conflicts, there are attempts to encourage sanitation of language and distort reality; in many occasions there is use of language to demonize groups and normalize violence. Communication hence can be said to fuel all forms of violence – direct, structural and cultural. Using case studies of integrating Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent communication in different settings and social institutions, the paper will look at how this approach of nonviolent communication can help in bringing change in attitude and behavior of the conflicting parties and aid in the resolution of the conflict.

Introduction

In a training program organized by Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti, New Delhi with a Police Academy, Khudmukhtiar Dev Singh, a police officer shared his experience of having worked with a Station House Officer (SHO) in the initial stages of his career. This case study explains how a SHO can promote nonviolent communication in policing. He said:

- Ease of accessibility: Anyone in distress who approaches the police station would not find any difficulties in meeting the SHO. Right from sentry to beat constable, all would ensure that the person was at ease when they ap- proached the police station.

- When the person met the SHO, he would be asked politely to sit The SHO, showing full interest, would ask about the concerns and problems. This explains the importance of the right attitude and behaviour which is crucial for nonviolent communication. His body language was friendly and affable.

- The SHO would then call the waiter to serve water to make the person more comfortable. Again, this is a case of the right attitude and behaviour.

- One of the important attributes of nonviolent communication is active listening. Mr Singh said the SHO possessed enormous patience and listened attentively to the problem.

- Nonviolent communication also demands sincerity in addressing The SHO would then call the Investigating Officer and ask him to seriously work on the complaint.

- Mr Singh also narrated how the SHO in the evening always made it a point to go around the area under his charge and meet his beat constables posted in different places. This is an important attribute of a good team leader and how a leader reaches out to his subordinates.

- The SHO also reached out to people of the area, this was a confidence-building measure with the public.

- When after two years the SHO was transferred, people of the area gave him a rousing farewell.

Kundu and Sinha (2021)

This case study underlines the essence of integrating nonviolent communication in public and social institutions. This also showcases how those working in public institutions can make a difference in their dealings with citizens when they use tools and strategies of nonviolent communication. This importance of the use of nonviolent communication in public institutions and the public sphere can be a starting point to address issues of conflicts mostly emanating from toxic use of communication. Right from an individual level, to families, in our institutions, communities and at the world level, encouraging and promoting a nonviolent communication ecosystem has become a critical requirement for furthering the goals of culture of peace and constructive resolution of conflicts. Disenchantment and adverse views of the functioning and policies of different institutions can lead to conflict situations; so the challenge is deeper engagement and constant dialogue for a harmonious relationship to evolve. Nonviolent communication precisely helps for such engagement and dialogues to evolve.

Further, a nonviolent communication ecosystem has become a necessity across cultures and at the global level in view of increasing forms of violence and rampant misuse of communication tools to normalize this violence. At a time when different actors of the society have the ability to use communication to amplify disinformation and toxicity to create divisiveness with impunity, the urgency to promote use of nonviolent communication in the communication architectures of institutions and societies has become significant.

Here in the context of conflicts across the world, it would be worthwhile to look at the global developments in armed conflicts, peace processes and peace operations. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s Yearbook 2022, there were active armed conflicts in about 46 states in 2021. (SIPRI, 2022) An important observation of the Yearbook was that most of these conflicts were intrastate in nature wherein conflicts arose between different groups or between government forces and other non-state armed actors. Besides conflict-related fatalities, the report talks about crisis arising out of population displacement, food insecurity, major humanitarian needs and violations of different international laws.

Meanwhile in another report, Alert 2022! Milian et. al. (2022) argue, “Most of the main motivations behind the armed conflicts in 2021 had to do with the domestic or international policies of the respective governments or the political, economic, social or ideological system of a certain state, which led to struggles to gain or chip away at power.”

Further, a UN report notes, “New, more complex and more sophisticated threats re- quire imaginative and bold responses, and strengthened collaboration between states, as well as the private sector and civil society. Institutional boundaries must also be bridged, so that political, human rights, and development partners can work in concert. (https:// www.un.org/en/un75/new-era-conflict-and-violence)

Fossati (2022) talking of different contemporary conflict resolution processes, their diagnoses and therapies points out how since 1989 different conflicts ‘have crystallized incompatibilities among different nations and/or civilizations, and that many conflicts have degenerated into wars’. Fossati calls these conflicts as cultural as they ‘involve collective identities, along ethnic, linguistic or religious cleavages’. When issues like identities whether ethnic, linguistic or religious cleavages are involved, communication has a significant role to play either in exacerbation of the conflict or in contributing to the healing process.

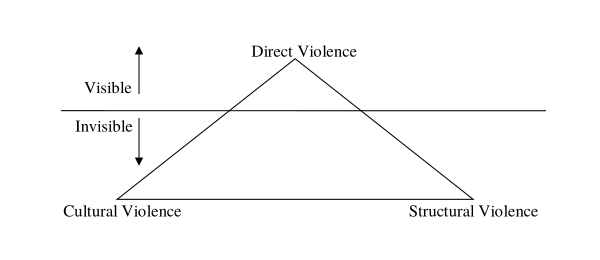

Each of the conflicts highlighted in the reports as discussed above can be analyzed in the context of Johan Galtung’s triangle of violence. (Galtung, 1969) Different forms of direct violence are involved in these conflicts. If the Alert 2022! Report is perused, it talks about the significant rise in the number of civilian victims in 2021. It also talks on attacks on health and medical staff. Besides the report points out on how there was rampant use of sexual and gender-based violence perpetrated against civilians by both state and non-state armed actors. The worst affected in these cases are women and girls. Forced displacement of people from their homes are important components of direct violence and the Alert 2022! Report cites a UNHCR data which points out that by the end of 2020, there were 82.4 million forcibly displaced people worldwide.

Continued violence which seriously disrupts the lives of citizens are also contributory factors to weakening of institutions. All these cases of direct violence leads to different types of structural violence. These may include food insecurity, deprivations, breakdown of health facilities, etc. The direct and structural violence are contributing to cultural violence and vice versa. Through use of different communication tools, many of these cases of direct violence and the different obvious forms of structural violence are highlighted in a way that may be legitimatized and even get acceptable in the society. Further these forms of violence may be portrayed in such a way wherein citizens become unmindful of reality, in fact the reality is made opaque. When this is done, people may not see the violent act or may start to believe that the violent act is not violent at all.

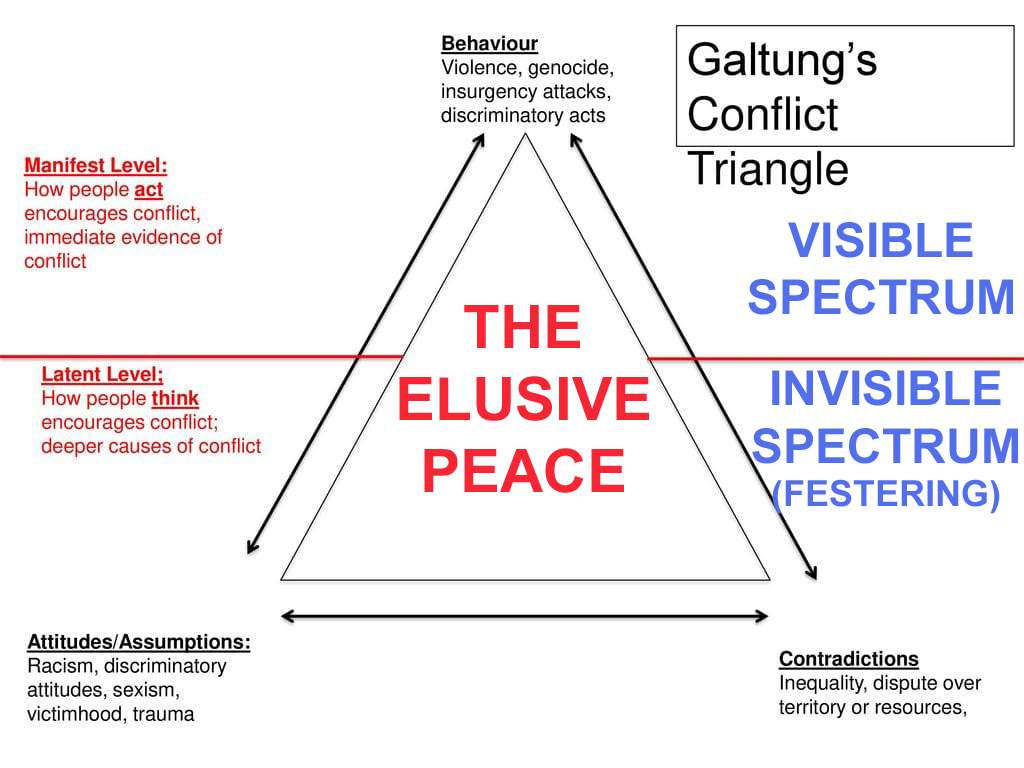

Here it can be stated that each of the conflicts can be explained in terms of Galtung’s conflict triangle. (Galtung, 2009 & Ercoskun, 2021) For instance, an on- going conflict in country Z can be analyzed in the context of the prevalent attitudes of the conflicting parties. Awareness of the attitudes and perceptions of the conflicting parities are important if any genuine efforts are to be made for resolution of the conflict. In conflict situations, the attitude of the conflicting parties can be strongly hostile with each party having negative stereotypes of the other. Further, attitudes and perceptions are critical in influencing the behavior of the conflicting parties. With hardening of stands, there can be more toxic behavior of provocations and use of violent language. This can be deterrents for the parties to see the benefits that could accrue from peaceful resolution of the conflict. In violent conflicts, the behavior of the parties could be coercion and even destructive attacks on each other. Finally, in the analysis of the conflict, we have to understand the contexts and sub-contexts at a deeper level. We have to understand that the conflict arises due to contradictions of the real or perceived goals of the conflicting parties, these could be due to conflict of interest on different issues or dysfunctional relationships between the parties.

If we carefully try to delineate the elements of this conflict triangle, we will find that communication is one of its central pillars. Attitudes and perceptions of the conflicting parties are expressed through different forms of communication. Further, behavior whether through toxic language, provocations and posturing are expressed through use of tools of communications whether verbal or nonverbal. Further the contexts and sub-contexts can be analyzed through understanding of historical relationships, different communicative acts of the conflicting parties and the reasons of conflict of interests.

Hence for resolution of the disputes, one of the critical requirements is promotion of efforts to ensure a healthy communication ecosystem in all our institutions. Whether efforts to change negative attitude or perceptions or bring changes in toxic behavior, use of strategies and tools of healthy communication is significant. It is here the role of nonviolent communication assumes importance. Hence the overarching goal of this chapter is to identity different examples and then try to establish the intrinsic link of nonviolent communication with the constructive resolution of conflicts and a culture of peace. There are different schools of thought which explains nonviolent communication. In fact nonviolent communication has been part of Indian traditions and culture right from ancient times. (Kundu, 2020)

For instance, Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 17, Stanza 15 literally says, “Austerity of speech consists in speaking in a manner that will not agitate the minds of the listeners or enkindle the base emotions of the listener or his passion; the communication should be true, it must be beneficial to the listener and also pleasant. One should also engage in self-study.” One of the important proponents of nonviolent communication in modern times have been Mahatma Gandhi and his influence to imbibe and work for nonviolence not only has traction in India but globally. Many of the global nonviolent movements have been influenced by the Mahatma. This chapter will focus on the Gandhian approach to nonviolent communication. It can be an important starting point of analyzing and linking Johan Galtung’s conflict triangle using the Gandhian nonviolent communication. It may also be mentioned that Galtung himself was much influenced by Gandhi. Also, the chapter can also be a reference point to analyze different conflicts across the world and find ways to their resolution using Gandhian nonviolent communication.

Understanding the Essence of Nonviolent Communication in Resolution of Conflicts

Kundu (2022b) describes nonviolent communication as a holistic communication approach which encompasses the entire gamut of our communicative efforts whether our intrapersonal communication, interpersonal, group, communication in the society at large and also our symbolic communication with nature and all other living beings. Senior Gandhian, Natwar Thakkar uses the Gandhian praxis to share his understanding of nonviolent communication (cited in Kundu, 2018) as he explains its holistic nature and delves on the spirit of human interconnectedness as the guiding pillar of nonviolent communication. Thakkar in his expansive explanation of nonviolent communication underlines its importance for deeper engagement and emotional bridge building.

The role of nonviolent communication in influencing attitudinal and behavioral change amongst ordinary citizens in conflict areas has been amplified by Masood Siddhu (2022) who studied the impact of training in nonviolent communication amongst a selected group of youth in Yemen, a country which finds itself in a state of intrastate conflict. Through a series of expert interviews and structured qualitative interviews of the participating youth, Masood Sidhu argued on the importance of use of nonviolent communication for constructive resolution of conflicts and transformation of relationships amongst the conflicting parties. Those who were interviewed felt that the traditional methods of dispute resolution in the Yemeni society can be strengthened with the integration of nonviolent communication. (Masood Sidhu, 2022).

The participants also underlined the significance of Gandhian approach to non- violence and nonviolent communication as a panacea to end vicious conflicts going around the world. Masood Sidhu (2022) cites Dr A L Ghaffari, a senior official in Yemen who pointed out that ‘there was need to bring Gandhi’s spirit in Yemen’s re- sistance to armed conflicts that the country was facing’. “We have to create a ground stand for Gandhi’s mission in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. Gandhi’s principles of nonviolence should be the guiding spirit for youth across the world to sway them away from specter of violence,” he pointed out in the expert interview.

According to Masood Sidhu, Abdualgaleel Khaled Ayish Kodaf, a local youth coordinator underlined on why the five-pillars of Gandhian nonviolence and different elements of Gandhian nonviolent communication needs to be introduced amongst youth especially those from conflict zones. “Gandhi’s nonviolent communication was a powerful antidote to the phenomenon of hate and violent communication grip- ping many parts of the world, Ayis Kodaf argued during the interview,” Masood Sidhu added.

Further in the context of Ethiopia’s Tigray crisis, Obuyi (2021) argues on the need to for adoption of Gandhian pillars of nonviolence and nonviolent communication for addressing the conflict situation. Obuyi notes, “Respect is one of such pillars, which essentially seeks to affirm the need for upholding human dignity and shying away from any tendencies that may jeopardize the same. Understanding, a good virtue that stems from the need to be considerate to each other views but also accommodating one another is an important aspect worth practice in the Ethiopia crisis. Excerpts from the forgone discussion have alluded to the lack acceptance and the absence of appreciation which are key ingredients to harmonious living and coexistence. Last, but not least would be the virtue of compassion; the act of kindness and love for one another are building blocks for lasting relationship. As a passionate player for peace and non-violent conflict resolution the author has huge sense of conviction that the pillars, as embedded in the five major virtues of humanity can be an important breakthrough towards the turmoil in Ethiopia.”

The five pillars of Gandhi’s nonviolence have been beautifully explained in the book of the Mahatma’s grandson, Arun Gandhi (2017). These include:

- respect,

- understanding,

- acceptance,

- appreciation, and

- compassion.

Meanwhile Mishelia et. al. (2022) sharing about the impact of their training of vigilante groups in Yobe state of Nigeria in Gandhian nonviolent communication noted, “The perceptible change in attitude and behavior of the vigilantes found as a result of the training in nonviolent communication underlines the importance of a sustained training program.”

Mishelia et. al. (2022) shares the experiences of about 270 junior vigilante of- ficers which he and his team in Hope Interactive trained in Gandhian nonviolent communication. The participants in general observed that their initiation to the world of nonviolent communication helped them change their perspectives on how con- flicts could be resolved. The tools the participants acquired gave them new insights on how to respond to parties involved in conflicts. They talked how use of nonviolent communication helped in greater engagement with the community and emotional bridge building.

For instance, Mishelia et. al. cites a vigilante officer Zanna Kadiri who pointed out how understanding Gandhian pillars of nonviolence ‘helped him identify his strength and weaknesses which carrying out his duties as a community vigilante’.

In view of the examples of use of Gandhian nonviolent communication in different difficult situations in different countries as cited above, an important pointer which emerges is how it can be a significant instrument for encouraging dialogues in conflict situations. Before we delve into this aspect further, it would be apt to understand the explanation of the Gandhian model of nonviolent communication. Based on the principles of human interdependence and the cosmocentric approach to human nature, the Gandhian model of nonviolent communication necessitates the use of nonviolence in all aspects of communication, whether verbal, nonverbal, our thoughts or ideas. (Kundu, 2022a). It underlines the essentiality of self-discipline, self-restraint, openness, flexibility, mutual respect, love and compassion in all our interactions. The Gandhian model reflects the principles of deep humanism and solidarity. Its assimilation helps not only individuals but institutions and also societies to contribute towards a communication ecosystem that is based on values and ethics. Continuing the analysis of using the Gandhian model of nonviolent communication, for instance, Galtung (1990) talks about religion and ideology as those aspects of culture which can be used to ‘justify or legitimize direct or structural violence’. In this context, Mishelia et. al. (2022) talks of Haruna Abubakar, a vigilante officer who observes that the knowledge gained through the training in nonviolent communication has ‘minimized the chances of taking communal conflict cases to police stations’. They talk of how the training has led to the establishment of a dialogue platform in the community which comprised of community members, vigilante officers, community heads and other stakeholders.

Further, arguing the role of nonviolent communication in bringing transformational changes in the attitudes and behaviors of the conflicting parties, it can be underscored how the five-pillars of Gandhian nonviolence can help changing the negative emotions and hostility to that to dignity and mutual toleration. For hostility to end, mutual toleration is critical. Here Gandhi has important guidepost for the en- tire humanity as he says, “The golden rule of conduct, therefore, is mutual toleration, seeing that we will never all think alike and we shall see Truth in fragment and from different angles of vision. Conscience is not the same thing for all. Whilst, therefore, it is a good guide for individual conduct, imposition of that conduct upon all will be an insufferable interference with everybody’s freedom of conscience.” (Young India, 23-9-1926)

An important dimension of the Gandhian model of nonviolent communication is nonviolent persuasion. (Kundu, 2022a). From hostility and toxic approach to each other in conflicts, when nonviolent communication becomes the fulcrum of the efforts to resolve the conflict, then the use of nonviolent persuasion becomes an important tool with the conflicting parties. Further, as nonviolent communication entails nonviolence in speech and action and the art of self-restraint (Kundu, 2022a), its use is likely to bring perceptible change in the behavior of those in conflict. For in- stance, Mishelia et. al. (2022) had elaborated on how vigilantes had become violent and hence the need for the training in nonviolent communication. Here they cite the experience of one of the vigilante officers who said, “The vigilantes generally have no friends in the community and are always avoided by community members. But now due to the assimilation of principles of nonviolent communication, community members now see us as their friends and are supporting us greatly in carrying out our activities. Due to this new development, we now have an office in the community where an investigation is being carried out on issues that serve as a threat to peace.”

An important dimension of the Gandhian approach is how it entails the evolution of an individual to a higher plane of values and ethics and respect for human dignity. As conflicts arise due to contradictions of real or perceived goals of the parties involved, when nonviolent communication becomes the instrument to diffuse the dispute, then the parties involved approach it within the framework of values and ethics. This can help in the process of conflict transformation.

A critical element of the Gandhian approach to nonviolent communication is the power of love. For conflict transformation to happen, the aim would be on how this power of love will be able to draw the conflicting parties together. Here Gandhi (1960) had said, “The fact that there are so many men still alive in the world shows that it is based not on the force of arms but on the force of truth or love. Therefore, the greatest and most unimpeachable evidence of the success of this force is to be found in the fact that, in spite of the wars of the world, it still lives on. Thousands, indeed tens of thousands, depend for their existence on a very active working of this force. Little quarrels of millions of families in their daily lives disappear before the exercise of this force. Hundreds of nations live in peace.”

The central elements of Gandhian nonviolent communication as we have noted thus far include the five-pillars of Gandhian nonviolence, the essence of self-restraint, and nonviolence in all our communicative efforts, the values of human dignity and love. The aim of the Gandhian approach to conflict resolution was not to hate the antagonists but make all attempts to end the antagonism. These frameworks of humanism as envisioned and acted upon by Mahatma Gandhi helps individuals turn inwards. Turning inwards for our deeper humanity is the overarching goal of Gandhian nonviolent communication and conflict resolution principles. It helps in seeing the goodness of all human beings; which is important for resolution of any dispute. Seeing goodness in others is an important dimension of Gandhian nonviolent communication which helps in deeper engagement and emotional bridge-building. Gandhi gave great importance to goodness as he equated it to God; he noted, “Goodness is God. Goodness conceived as apart from Him is a lifeless thing and exists only whilst it is a paying policy. So are all morals. If they are to live in us, they must be considered and cultivated in their relation to God. We try to become good because we want to reach and realize God. All the dry ethics of the world turn to dust because apart from God they are lifeless. Coming from God, they come with life in them. They become part of us and ennoble us.” (Harijan, 24-8-1947)

So, assimilation of the Gandhian principles as enumerated above are critical which needs to be assimilated not only at the individual levels but also at institutional levels; these can help in avoidance of violent conflicts and also constructive resolution of disputes.

Further, Kundu (2022 a) lists out another important dimension of Gandhian non- violent communication. He notes, “Mahatma Gandhi’s communication strategy was to reach the hearts of the masses through constructive work for social and economic emancipation. For instance, his Talisman is a powerful statement about how each needs to introspect on what they are doing for the last person of the society. It under- scores the essence of empathetic connections.” The essence of constructive work for social and economic emancipation especially for those who can be described as the last person of the society is a powerful strategy to overcome structural violence in our societies. When policies and instruments are aimed at reaching the hearts of the people for their social and economic emancipation much of the problems arising out of structural violence can be countered.

Using these tools of Gandhian nonviolent communication will also help in humanizing the communicative efforts of various stakeholders and discourage the practice of legitimizing violence and other deprivations. Misrepresentations and false stereotypes which becomes the norm in conflict situation can be prevented if nonviolent communication is integrated in the communication architecture of public and social institutions.

Conclusion

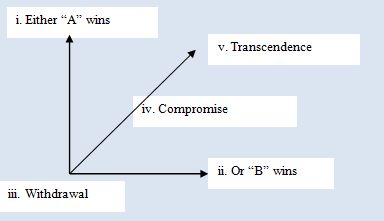

This chapter tied to establish a link between Johan Galtung’s triangles of violence to Gandhian nonviolent communication. It tried to examine through different examples on how direct, structural and cultural violence can be dealt with using Gandhian nonviolent communication. The chapter also looked at Galtung’s explanation of the conflict triangle, it then tried to argue on how the Gandhian approach to nonviolent communication can bring perceptible changes in attitudes and behaviours of those in conflict while aiding the process of removing contra. Besides, it tried to look at how this approach can help in easing of contradictions thereby contribute to reconciliation. Overall, it can be underlined that the efficacy of the Gandhian approach to nonviolent communication lies in its deep assimilation and nurturing whether at individual level, family level, institutional level, societal level or the global level. Only its deep assimilation can help in contributing towards avoidance of conflict and for a culture of peace and nonviolence.

To conclude, it would be apt to revisit this quote of the Mahatma as noted by the former President of India, S Radhakrishnan (1958), which can keep reminding us on the deep strength of our humanity and that we are all intricately connected, “By a long process of prayerful discipline I have ceased for over forty years to hate anybody. All men are brothers and no human being should be a stranger to another. The welfare of all, Sarvodaya, should be our aim. God is the common bond that unites all human beings. To break this bond even with our greatest enemy is to tear God Himself to pieces. There is humanity even in the most wicked.”

References:

Ercoskun, Burak (2021).On Galtung’s Approach to Peace Studies. Lectin Socialis, Volume 5, Issue 1, 1-7, January 2021.

Fossati, Fabio (2022). Contemporary Conflict Resolution Processes: Diagnoses and Therapies. https://www.transcend.org/tri/downloads/FabioFossati2018-ContemporaryCo nflictResolutionProcesses-DiagnosesAndTherapies.pdf; accessed on April 10, 2023.

Galtung, Johan (1969). Violence, Peace and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research; Vol. 6, No. 3 (1969); pp– 167-191.

Galtung, Johan (1990). Cultural Violence. Journal of Peace Research; Vol. 27. No. 3. 1990. pp. 291-305.

Galtung, Johan (2009). Theories of Conflict. Transcend Peace University, Retrieved from https://www.transcend.org/files/Galtung_Book_Theories_Of_Conflict_single.pdf.

Gandhi, Mahatma (1960). All men are brothers: Life and thoughts of Mahatma Gandhi as told in his own words. Krishna Kriplani (Ed.). Navajivan, India.

Gandhi, Arun (2017). The Gift of Anger. Gallery/Jeter Publishing.

Kundu, Vedabhyas (2018). Nurturing Emotional Bridge Building: A Dialogue with Nagaland’s Gandhi. Peaceworks, 8 (1), June 2018. Retrieved from https://peaceworks.in/ issuepdf/76573Peaceworks_Vol8_Issue1_2018.pdf

Kundu, Vedabhyas (2020). Exploring the Indian Tradition of Nonviolent Communication. International Journal of Peace, Education and Development, 8(2): 81-89, December 2020. doi: 10.30954/2454-9525.02.2020.4

Kundu, Vedabhyas and Sinha, Shristi (2021). Exploring Nonviolent Communication. Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti & Bharathiar University.

Kundu, Vedabhyas (2022a). Exploring the Gandhian Model of Nonviolent Communication and its Significance; Gandhi Marg. 44 (1), April-June 2022. Retrieved from https://www. mkgandhi.org/articles/Gandhian-model-of-nonviolent-communication.html

Kundu, Vedabhyas (2022b). Nonviolent Communication for Peaceful Co-existence. In L.R. Kurtz (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict, Vol. 4. Elsevier, Academic Press.

Mshelia, Andrew Wayuta and Birma, Mshelia (2022). Transformational effect of training in nonviolent communication: A case study of training of vigilante groups in Yobe State, Northeast Nigeria; International Journal of Peace, Education and Development; 10(01): 01-07; June 2022. doi: 10.30954/2454-9525.01.2022.2.

Milian, Navarro Ivan; Aspa, Maria Royo; Garcia, Jordi Aspa; Arestizabal, Urrutia Pamela; Arino, Villellas Ana; Arino, Villellas Maria (2022). Alert 2022! Report on conflicts, human rights and peacebuilding. Escola de Cultura de Pau; Barcelona: Icaria, 2022.

Obuyi, Rehema Zaid (2021). Enhancing capacities in nonviolent communication to change perceptions and addressing root, proximate and tertiary causes of Ethiopia’s Tigray crisis; International and Public Affairs.5 (1). 2021; pp. 11-18; doi: 10.11648/j.ipa.20210501.13 Radhakrishnan, S (1958). Introduction. In Krishna Kriplani (Ed.). All men are brothers: Life and thoughts of Mahatma Gandhi as told in his own words. Navajivan, India.

Sidhu, Shazaf Masood (2022). Introducing Nonviolent Communication amongst Youth of Yemen: An Exploration of the Impact of the Intervention. International Journal of Peace, Education and Development; 10(02): pp. 01-05, December 2022; doi: 10.30954/2454- 9525.02.2022.2.

SIPRI Yearbook. (2022). Armaments, Disarmament and International Security. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Oxford University Press.

28 May 2023

___________________________________________

Vedabhyas Kundu is Programme Officer, Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti. Email: vedabhyaskundu.ahimsa@gmail.com

Download PDF file:

Exploring the Centrality of Nonviolent Communication

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER REMAINS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS

Tags: Conflict Mediation, Conflict Resolution, Conflict Transformation, Cultural violence, Direct violence, Gandhi, Johan Galtung, Nonviolence, Nonviolent communication, Peace Studies, Structural violence

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 11 Sep 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Exploring the Centrality of Nonviolent Communication for Resolution of Conflicts and a Culture of Peace, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: