Necessary Losses: The Life-Shaping Art of Letting Go

INSPIRATIONAL, 27 Nov 2023

Maria Popova | The Marginalian – TRANSCEND Media Service

“The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” Elizabeth Bishop wrote in one of the great masterpieces of poetry. “Every mortal loss is an Immortal Gain,” William Blake wrote two centuries before her in his beautiful letter to a bereaved father.

“The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” Elizabeth Bishop wrote in one of the great masterpieces of poetry. “Every mortal loss is an Immortal Gain,” William Blake wrote two centuries before her in his beautiful letter to a bereaved father.

We dream of immortality because we are creatures made of loss — the death of the individual is what ensured the survival of the species along the evolutionary vector of adaptation — and made for loss: All of our creativity, all of our compulsive productivity, all of our poems and our space telescopes, are but a coping mechanism for our mortality, for the elemental knowledge that we will lose everything and everyone we cherish as we inevitably return our borrowed stardust to the universe.

And yet the measure of life, the meaning of it, may be precisely what we make of our losses — how we turn the dust of disappointment and dissolution into clay for creation and self-creation, how we make of loss a reason to love more fully and live more deeply.

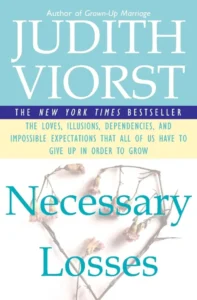

That is what Judith Viorst explores in her 1987 consolation of a book Necessary Losses (public library) — an inquiry into the profound and far-reaching relationship between our losses and our gains, revealing renunciation as a fulcrum of growth. She paints the vast landscape of loss upon which life plays out:

When we think of loss we think of the loss, through death, of people we love. But loss is a far more encompassing theme in our life. For we lose not only through death, but also by leaving and being left, by changing and letting go and moving on. And our losses include not only our separations and departures from those we love, but our conscious and unconscious losses of romantic dreams, impossible expectations, illusions of freedom and power, illusions of safety — and the loss of our own younger self, the self that thought it always would be unwrinkled and invulnerable and immortal.

[…]

These necessary losses… we confront when we are confronted by the inescapable fact… that we are essentially out here on our own; that we will have to accept — in other people and ourselves — the mingling of love with hate, of the good with the bad;… that there are flaws in every human connection; that our status on this planet is implacably impermanent; and that we are utterly powerless to offer ourselves or those we love protection — protection from danger and pain, from the in-roads of time, from the coming of age, from the coming of death; protection from our necessary losses.

These losses are a part of life — universal, unavoidable, inexorable. And these losses are necessary because we grow by losing and leaving and letting go.

As a sculpture is shaped by what is chiseled off from the block of stone, so too are we shaped by what we lose — by choice, with all the complexities and difficulties of letting go, or by the scythe of chance, which takes away as impartially as it gives. Viorst writes:

The road to human development is paved with renunciation. Throughout our life we grow by giving up. We give up some of our deepest attachments to others. We give up certain cherished parts of ourselves. We must confront, in the dreams we dream, as well as in our intimate relationships, all that we never will have and never will be. Passionate investment leaves us vulnerable to loss. And sometimes, no matter how clever we are, we must lose… It is only through our losses that we become fully developed human beings.

We enter the realm of loss the moment the umbilical cord is cut to sever what Viorst calls the “blurred-boundary bliss of mother-child oneness” — the primal loss that sets off the ongoing task of becoming ourselves. From this origin point, she traces the lifelong vector of losses and gains:

Exchanging the illusion of absolute shelter and absolute safety for the triumphant anxieties of standing alone… we become a moral, responsible, adult self, discovering — within the limitations imposed by necessity — our freedoms and choices. And in giving up our impossible expectations, we become a lovingly connected self, renouncing ideal visions of perfect friendship, marriage, children, family life for the sweet imperfections of all-too-human relationships. And in confronting the many losses that are brought by time and death, we become a mourning and adapting self, finding at every stage — until we draw our final breath — opportunities for creative transformations.

In a sentiment the poet Mark Doty would echo — “you need to both remember where love leads and love anyway,” he wrote in his beautiful reckoning with love and loss — she adds:

We cannot deeply love anything without becoming vulnerable to loss. And we cannot become separate people, responsible people, connected people, reflective people without some losing and leaving and letting go.

Complement Necessary Losses, which goes on to explore the many regions of loss in human life and how they can become frontiers of growth, with Hannah Arendt on learning how to live with the fundamental fear of loss, Thoreau on living through a loss, and Alan Watts on learning not to think of gain and loss, then explore two uncommon lenses on loss: fractals and chlorophyll.

_______________________________________

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

Go to Original – themarginalian.org

Tags: Death, Inspirational, Life, Spirituality

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.