The Forgotten (Part 5): The First Nations–Indigenous Tribes of Canada

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 18 Dec 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

This publication contains critical narrative and information about the First Nations as a forgotten minority community. Every care has been taken to respect the cultures and traditions; the author intends no disrespect to the elders and members of the First Nations. He humbly and unequivocally apologises for any offenses.

***************

“Indigenous cultures’ languages, traditions and values are endangered entities about to become totally extinct and forgotten in the present world of materialism.” [1]

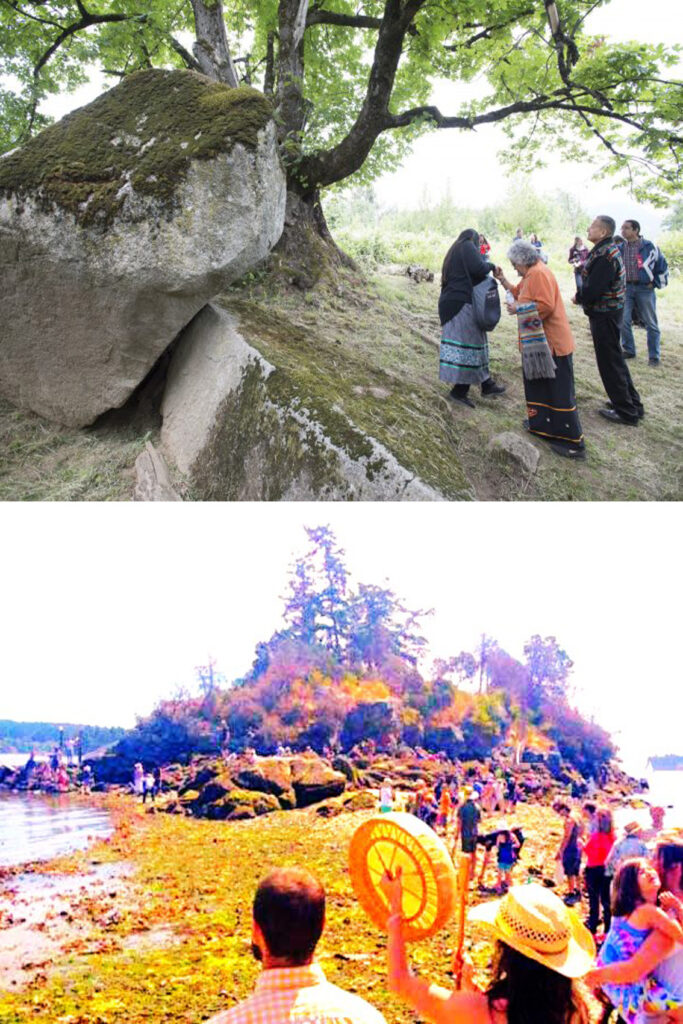

The First Nations, Rich and Spiritual, Ancient Traditions, observed in British Columbia, Canada. These vibrant practices are sadly eroded and forgotten in the 21st century.

Photo Credit: BBC Lonely Planet

This paper, Part 5, in the series on the Forgotten Communities,[2],[3],[4],[5],[6] globally, highlights eradication of the family values, cultures, traditions and ancestral beliefs of the original, inhabitants of the northern regions of North America, presently Canada, by colonialists, imperial occupying forces, who initially arrived under the pretext of converting “the pagans” and bringing them into the fold of Christianity, using the early Christian missionaries.

They came into the country clearly, with a hidden agenda. In the process, the children of the First Nations were forcibly removed, actually abducted from their parents, indoctrinated, killed and buried in mass graves, around these Catholic assimilation schools in different regions of Canada.[7] Effectively, this was a cultural genocide, of the children of the First Nations, as well as a reprogramming of the basic life style, entrenched in deep indigenous knowledge systems and extended family values, to replace these with western traditions and materialistic aspects of life, by the colonial British and other European nations, including France.

The subsequent internal community conflict which was generated as a result of this transformation, resulted in the emergence of a community of lost tribes, with a directionless leadership, indoctrinated by western propaganda, even to the extent of eradicating their vernacular languages and high codes of moral conduct. This was indeed a sad and serious indictment on the invaders and occupiers of the land and minds of the First Nations of Canada, as they accomplished elsewhere in the world.

This is as evidenced by the ethnic cleansing and genocidal killings of Palestinians in Gaza, including scores of targeted assassinations of journalists[8], as well as in the occupied territories by the brutal and ruthless government of Benjamin Netanyahu[9] and the people of Israel, who must bear a collective responsibility for the deaths of over 19000 Palestinians, as of 14th December 2013, including civilians, women and children, in the current war on Gaza, since October 07th 2023[10],[11] while the Palestinians were fighting for their freedom, from the occupying Zionist forces, officially since 1947[12] and even prior to that, historically.

This death, destruction and the suffering of the First Nations, in a psycho-social manner is analogous to the physical human ethnic cleansing and physical genocide which is experienced by the Gazains, the Kashmiris, the Rohingyas, the Uyghurs and the Syrians in different regions of the politico-physical world, in the 21st century, by the different oppressive political regimes. These different regional crusades, driven by nationalistic fervour and the inherent ethos of ethnophobia by these ruthless governments, cause an enormous degree of Peace Disturbance[13], [14] within these marginalised, minority communities.

The First Nations Defined: Who are these marginalised Communities?[15]

Collectively, these are groups of native, indigenous people, who lived on the North American continent long before they were occupied by European explorers. The use of this term reflects a recognition of the historical and cultural continuity of Indigenous peoples in Canada and acknowledges their status as the original inhabitants of the land. They are often associated together by their common language and culture. These natives have been known as Indians, American Indians, Native Americans, the native races of North America, First Nations and other similar terms. Original records and books about them may be listed or catalogued under any or all of these terms. Almost none of the American Indian groups had a written language. Most of the early records regarding them were created and preserved by individuals and governments dealing with the natives. The Native Americans used oral history methods to preserve their history and culture.

However, in a purist sense, the term “The First Nations” refers to the various “Aboriginal” peoples in Canada who are neither Inuit nor Métis. It is a term that came into common usage in the 1970s to replace the term “Indian.”, which was considered derogatory.

Some key facts about the First Nations in the 21st century:

- There are over 600 recognised First Nations governments or bands across Canada. They have unique histories, languages, cultural practices and connections to the land.

- First Nations people live across Canada, from large cities to remote rural areas. However, many reserves and First Nations communities continue to be located on ancestral lands.

- As of 2016, there were over 970,000 people in Canada identifying as First Nations people, making up about 3.5% of the total Canadian population.

- Common First Nations cultural/linguistic groups include the Algonquian peoples across Eastern/Central Canada, Iroquoian peoples like the Haudenosaunee in Quebec/Ontario, Salish peoples in BC, as well as diverse Athabaskan, Tsimshianic, Wakashan and other groups.

- Many First Nations communities continue to face significant challenges including the ongoing impacts of colonial policies and practices, disputes over land/resources with corporations and governments, lack of access to infrastructure and essential services, preservation of languages/culture, poverty, addiction, high suicide rates.[16]

- Advocacy at the tribal, provincial and national levels has focused on issues like improving services on-reserve, settling land claims, establishing self-government, supporting cultural resurgence, investigating missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, and reconciliation around Canada’s history with residential schools.

In summary, the First Nations encompasses a diversity of distinct Indigenous nations across Canada with unique histories tied to their ancestral and treaty territories. Advocating for their rights and well-being remains an important issue in present day Canada, a matter of national importance, which the Trudeau Government is trying extremely hard to reconcile and effect national cohesion. It is critical to understand that the term “First Nations” refers specifically to the indigenous peoples of Canada who are not Inuit or Métis. It does not apply to indigenous groups in other countries. Each country has its own terminology for the indigenous peoples living there prior to imperial, European colonisation:

- In the United States, the most common term is Native American or American Indian. This encompasses such groups as the Cherokee, Navajo, Sioux, Seminole, Iroquois Confederacy, and others. They would not be classified as First Nations.

- In New Zealand, the indigenous Polynesian people are known as Māori. They have their own distinct culture, language, and history and would not be considered First Nations.

- In South Africa, there are various ethnic groups like the Zulu, Xhosa, Basotho, Khoikhoi, and San people. “Hottentots” is considered an outdated, colonial term. These groups would also not be classified as First Nations.

- In India, the Dravidian peoples of southern India have their own ethnic identity and languages like Tamil, Malayalam, and Kannada. They are different from the Indo-Aryan groups of northern India. Neither would be called First Nations.

- The indigenous peoples of the Amazon rainforest consist of hundreds of distinct tribes throughout South America. Some larger Amazonian groups include the Guarani, Mapuche, Quechua, Aymara, and Yanomami peoples. They would not be First Nations either.

Therefore, the First Nations only refers to the wide variety of indigenous bands and peoples recognised within the borders of contemporary Canada. Other countries worldwide have their own terminology and classificatory systems for the native peoples living there. It is to be also noted that the Metis and Inuits are not classified as First Nations in Canada, according to some sources for the following reasons:

Métis:

The Métis are one of the three recognized Indigenous groups in Canada, along with First Nations and Inuit. The Métis have a distinct cultural identity and heritage that emerged through the intermingling of Indigenous peoples, particularly Cree and Ojibwe, with European settlers, primarily of French and Scottish descent. The Métis played a crucial role in the fur trade and were historically concentrated in the Prairies, as well as parts of Ontario and British Columbia. Today, Métis communities can be found across Canada. Métis individuals live in both urban and rural settings, with significant populations in provinces such as Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and parts of Ontario and British Columbia. Métis Nation, the representative government for the Métis people, is organized at the national, provincial, and local levels. Métis citizens often reside in Métis settlements, urban centers, and traditional territories. Métis individuals are engaged in a variety of professions and activities. Many are involved in industries such as education, healthcare, business, arts, and cultural preservation. The Métis Nation has been actively working on issues related to self-governance, land rights, and cultural revitalization. Métis festivals and events celebrate their unique heritage, including Métis music, dance, and traditional crafts.

- The Métis emerged out of unions between European fur traders and First Nations women starting in the late 17th century. A distinct Métis culture developed speaking Michif and practicing certain traditional customs.

- The Métis people established themselves predominantly in areas like the Red River region of Manitoba. Historically important figures include Louis Riel who led two major Métis resistance movements against the Canadian government.

- Unlike First Nations, the Métis did not sign treaties or have reserved lands set aside for their exclusive use. They developed a more nomadic lifestyle than other indigenous groups in Canada.

- Today, being Métis means having ancestral ties to these historic Métis communities. Métis have their own unique identity, culture, struggles and advocacy organizations separate from First Nations peoples.

Inuit:

The Inuit are Indigenous peoples who primarily inhabit the Arctic regions of Canada, Greenland, the United States (Alaska), and Russia. In Canada, the Inuit are recognized as one of the three Indigenous groups alongside First Nations and Métis. Inuit communities are scattered across the Arctic regions of Canada, with the majority residing in Nunavut, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories, Nunavik in Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Labrador, Newfoundland, and Labrador. The harsh and remote environment of the Arctic has shaped traditional Inuit lifestyles and continues to influence contemporary life in these regions. Traditionally, Inuit were skilled hunters, relying on subsistence practices such as hunting marine mammals, fishing, and gathering. Today, while maintaining cultural practices, many Inuit are also engaged in modern professions, including government, healthcare, education, and arts. The Inuit have a rich cultural heritage expressed through their language, Inuktitut, as well as through art forms such as carving, printmaking, and throat singing.

Both Métis and Inuit communities are diverse, and individuals within these communities pursue a range of activities, professions, and cultural practices that reflect their unique identities and contributions to Canadian society.

- The Inuit are the indigenous peoples of Arctic regions like Nunavut, Nunavik (Northern Quebec), Nunatsiavut (Labrador), and the Northwest Territories. Their language and culture sets them apart.

- Traditionally Inuit were nomadic, traveling and hunting across vast Arctic terrains. Today most Inuit live settled lives in communities across Canada’s North. Issues like climate change/environmental damage heavily impact them.

- The Inuit have forms of self-government such as the territory of Nunavut. Their history and treaty rights also differ significantly from other indigenous peoples in Canada.

In summary, while facing many common struggles, the Métis and Inuit have distinct histories, cultures, languages, and rights from other groups now classified as First Nations in Canada. Métis and Inuit form their own recognised aboriginal groups. Collectively, they all make up the indigenous peoples of Canada, but NOT the First Nations” which is a term , exclusively reserved for the other, “pure” indigenous people of Canada. Therefore, the Metis an Inuits are a “hybrid” race as the so classified Coloured in South Africa[17]. There are some notable similarities and differences between the origins of the Métis[18] and Inuit[19] in Canada and the Coloured population in South Africa:

Similarities:

- Both the Métis and Coloured populations emerged from early contact and mixing between European colonizers and indigenous groups. The Métis from First Nations intermixing, and the Coloured population from the Cape Colony.

- Like the Coloured population in South Africa, the Métis and some Inuit groups have relatively distinct mixed ancestries, cultures, languages (e.g. Michif), and identities separate from habitually defined indigenous tribes/bands.

Differences:

- The Coloured identity has traditionally been more institutionalized (birth certificates categorizing the mixed-race population as “Coloured”, for example) within South Africa’s imposed racial classificatory system. Whereas to be recognized as Métis in Canada, proof of ancestral connection to historic Métis populations is required.

- The Inuit as a whole are more widely recognized as a distinct aboriginal group alongside First Nations groups, rather than necessarily being labeled a “hybrid” population akin to the Coloured label. They have more firmly defined communities and territorial regions.

- Métis and Inuit indigenous rights ultimately have firmer legal constitutional protections in Canada today compared to the status of Coloured groups in South Africa who still experience extensive marginalization.

In summary, while the Métis share certain similarities to emerging mixed-race groups like the Coloured population under colonial regimes, they and the Inuit have in many ways moved beyond a “hybrid” label in Canada to be accepted and defined as distinct recognized aboriginal peoples. However, there are still aspects that resonate across transnational indigenous identities shaped under settler colonial systems. Interestingly, a few anthropological experts include the Inuit and Métis under an expanded, conflated definition of “First Nations”, though this remains contested and controversial. There are a few reasons why some academics might take this stance:

- To emphasize the common experiences and impacts of colonialism and discrimination all indigenous groups in Canada have faced historically in spite of legal terminological differences today.

- Using “First Nations” as an overarching postcolonial term for all indigenous groups underscores the shared goals of recognition, rights, reconciliation, and cultural revitalization they seek in the present.

- It highlights that dividing Aboriginal identities into First Nations, Métis and Inuit neglects how fluid Indigenous identity formation has been across time for some individuals, families, and communities.

- Due to overlapping geographic territories and intermixing, clear-cut lines between groups are often challenged on the local community level leading some social scientists argue adopting a singular “First Nations” encompassing label is more realistic.

That said, the majority position still favours maintaining the separate legal and constitutional status of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples. Formally recognised collective rights, reserved lands, and negotiated treaties of these groups vary tremendously. An expansive “First Nations” term can obscure critically important political differences between Aboriginal groups in Canada that shape their identities, legal claims, and well-being to this day. While well-intentioned arguments are made, conflating First Nations, Métis and Inuit under a singular “First Nations” umbrella today remains contentious. There are good reasons for continuing defined national terminologies that recognise distinct histories and right, overall. However, there are indeed a few social scholars and anthropologists who have argued for expanding the definition of First Nations to include the Métis and Inuit, though it is certainly not the majority position. Some who have adopted this perspective include:

- Laura-Lee Kearns, an anthropologist at Memorial University[20]: She has conducted fieldwork with mixed-identity Acadian-Mi’kmaw communities in eastern Canada, contributing to debates around fluid Indigenous identity and corresponding categorical labels.

- Professor Will Kymlicka at Queen’s University[21] – A political/legal philosopher who has advocated for the rights of aboriginal groups. He sees similarities in the historic discrimination of First Nations/Métis/Inuit people under colonial structures as justification for a more unified “First Nations” categorization.

- Sociologist Dennis Foley[22] – He explored Métis identity formation and associated genealogical records challenging exclusionary approaches used to define Aboriginal cultural groups. He felt imposing state mandated blood proportions and ancestral proofs contradicted lived, self-identified indigenous realities.

- Dr. Émilie Cameron at Carleton University[23] – An anthropologist whose work bringing in Inuit perspectives has exposed contradictions between imposed governmental definitions of aboriginality versus actual belief systems, affiliations and families living these fluid identities in Arctic communities.

- Historian Keith Carlson[24] – He has studied oral histories documenting intricate kin networks spanning among First Nations, Métis and Inuit families which becomes lost through rigid, institutional identity labels that fail to capture this complexity on the ground level.

The arguments and rationale these researchers put forward provide some examples of perspectives advocating for reassessing the boundaries of terms like First Nations. The adoption of the term “First Nation” is part of the broader effort to recognize and respect the distinct identities, cultures, and histories of the diverse Indigenous peoples in Canada. It emerged as a way to move away from older and sometimes derogatory terms and to foster a more inclusive and respectful dialogue. The term “First Nation” is often used in conjunction with the names of specific Indigenous communities or nations. For example, the Cree Nation, the Haida Nation, or the Mohawk Nation are specific First Nations within the larger framework.

It is important to note that “First Nation” is just one of the terms used in Canada to refer to Indigenous peoples. The term is officially recognized and used in legal and political contexts, alongside other terms such as Métis and Inuit, to acknowledge the diversity of Indigenous identities in the country.

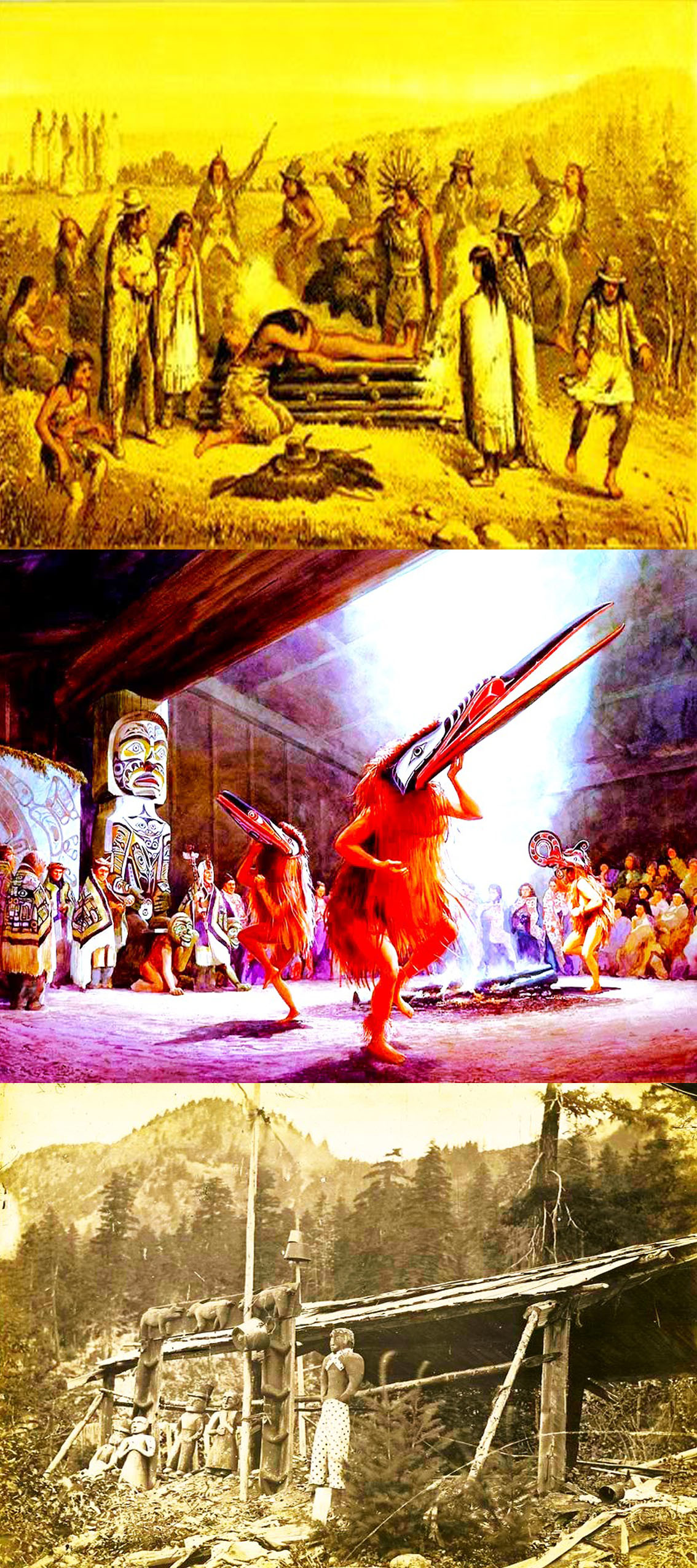

First Nations in traditional Tribal Attires for ceremonies

Top Left: Minister participating in First Nations Rituals, Worship and Festivals celebrated in Canada demonstrating and respecting the collective First Nations Spirituality.

Top Right: A First Nation Child holding the Ceremonial Tribal Drum and stick.

Bottom: First Nations Tribal Officials and child in full Tribal, Colourful, Ceremonial Regalia

The history of First Nations in Canada is complex and spans thousands of years. Indigenous peoples in Canada have diverse cultures, languages, and histories, and their experiences have been shaped by interactions with European colonisers, the impacts of colonisation, and subsequent government policies.

- Origins: Indigenous peoples in Canada have a long and rich history dating back thousands of years. The First Nations are made up of various distinct cultural and linguistic groups, each with its own unique heritage. They have lived on the land now known as Canada long before the arrival of European settlers. The question, often raised is where did the First Nations originated from anthropologically or did they arrive from the cold Artic regions to warmer regions south, noting that the epicentre of evolution of modern humans was in Sterkfontein region of South Africa? The origins and migration patterns of Indigenous peoples, including the First Nations in Canada, are complex and multifaceted. Anthropological and archaeological research continues to contribute to our understanding of human history, and while there are theories, it’s important to note that definitive answers may not be easily attainable due to the gaps in the archaeological record and the richness of diverse Indigenous histories.

There are several theories regarding the peopling of the Americas, and one predominant model is the Bering Land Bridge hypothesis: One widely accepted theory proposes that during the last Ice Age, sea levels were lower, exposing a land bridge called Beringia between Asia and North America. This allowed for the migration of human populations from Asia into North America. These early populations are thought to have gradually moved southward over thousands of years. This theory aligns with genetic evidence that indicates a common ancestry between Indigenous peoples in the Americas and certain populations in Siberia and East Asia. While the Bering Land Bridge hypothesis is a prevailing model, it’s not the only one, and researchers continue to explore alternative theories and refine existing ones. Some other hypotheses and considerations include: Some researchers propose that early populations may have followed coastlines, utilizing maritime resources as they moved southward along the Pacific Coast. Other evidence suggests that multiple migration routes and waves of migration may have occurred, contributing to the diversity of Indigenous cultures in the Americas. Some theories propose that populations could have arrived in the Americas from various directions, including southward dispersals from regions other than Beringia. Regarding the epicenter of human evolution, while the Sterkfontein region in South Africa has yielded significant fossil discoveries, the evolution of modern humans is understood to have taken place in different regions of Africa. The consensus among scientists is that anatomically modern Homo sapiens originated in Africa, and from there, populations migrated and dispersed to various parts of the world. It is crucial to approach discussions about the origins of Indigenous peoples with cultural sensitivity and respect for the diverse histories and perspectives of these communities. Indigenous oral histories, cultural knowledge, and traditions also contribute valuable insights to understanding their own origins and histories

- Colonisation: The arrival of Europeans, particularly in the 15th and 16th centuries, had profound effects on Indigenous populations. The fur trade, European diseases, and the arrival of settlers led to significant disruptions in Indigenous societies. Treaties were often negotiated between Indigenous nations and European powers, but these treaties were not always honored, leading to land dispossession and cultural disruption.

- Residential Schools and Cultural Suppression: In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Canadian government implemented policies aimed at assimilating Indigenous peoples into Euro-Canadian culture. One of the most harmful aspects of this assimilation policy was the establishment of residential schools, where Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families and subjected to cultural suppression, abuse, and neglect.

- Land Displacement and Treaty Rights: Land has been a central issue in the history of First Nations. Many Indigenous communities were displaced from their traditional lands through various means, and treaties signed with the Canadian government often did not uphold the rights and promises made to Indigenous peoples.

- Marginalization and Socioeconomic Disparities: Today, many First Nations communities continue to face socioeconomic challenges. These challenges include inadequate housing, limited access to education and healthcare, high rates of unemployment, and issues related to mental health and substance abuse. These disparities are often linked to historical injustices, discrimination, and ongoing struggles for land and resource rights.

- Land Rights and Self-Governance: There have been ongoing efforts by First Nations to assert their land rights and pursue self-governance. Land claims and negotiations with the Canadian government have taken place, and there is a growing recognition of the need for Indigenous self-determination and the implementation of treaties and agreements.

It is important to note that the experiences of First Nations are diverse, and there are many successful examples of cultural revitalization, economic development, and political empowerment within Indigenous communities. However, the history of colonization and its legacy continue to impact Indigenous peoples in Canada, contributing to ongoing challenges and efforts toward reconciliation. he present status of First Nations in Canada is diverse, as there are over 600 recognized First Nations, each with its own unique circumstances, challenges, and successes. The situation varies widely from one community to another. While there are ongoing challenges, there have also been efforts to address historical injustices and promote Indigenous rights and self-determination.

- Land and Resource Rights: Land rights remain a significant issue for many First Nations. Some communities have successfully negotiated land claims and treaties with the Canadian government, while others continue to advocate for recognition of their traditional territories and resource rights.

- Self-Governance: There has been a push for greater self-governance and autonomy among First Nations. Many communities are working towards establishing their own governance structures, legal systems, and institutions to better address the needs of their populations.

- Education and Health: There are disparities in education and healthcare outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. Efforts are being made to improve access to quality education and healthcare services in First Nations communities, with a focus on cultural relevance and community engagement.

- Economic Development: Economic opportunities and development vary among First Nations. Some communities have successfully pursued economic initiatives, such as resource development, tourism, and other business ventures, to create jobs and generate revenue.

- Special Privileges or Rights: It’s essential to clarify that the rights afforded to Indigenous peoples in Canada are not considered “special privileges” but are instead recognized as inherent rights based on historical treaties, land agreements, and the affirmation of Indigenous rights in the Canadian Constitution. These rights include hunting and fishing rights, the right to self-governance, and the duty of the Canadian government to engage in meaningful consultation with Indigenous communities on matters that may affect their rights and interests.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC): Canada[25] has been engaged in a process of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, acknowledging the historical wrongs, particularly related to the residential school system. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established to address the legacy of the residential schools and make recommendations for reconciliation. The TRC’s calls to action include steps for improving education, health, justice, and other areas for Indigenous communities.

It is important to recognise that the journey towards reconciliation is ongoing, and addressing the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization is a complex and multifaceted process. Efforts are being made at various levels, including federal, provincial, and Indigenous leadership, to address these issues and work towards a more just and equitable relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The discovery of unmarked graves of Indigenous children in Canada is a tragic and deeply disturbing aspect of the country’s history, particularly related to the residential school system. The residential schools were institutions that were established in the 19th century with the goal of assimilating Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture. These schools were often run by religious organisations, including various Christian denominations, with a significant role played by missionaries. The events leading up to the discovery of these graves involve several factors:

- Establishment of Residential Schools (19th Century): In the 19th century, the Canadian government, in collaboration with various religious organizations, established residential schools across the country. The primary objective was to assimilate Indigenous children by removing them from their families, communities, and cultural influences.

- Forcible Separation and Cultural Suppression: Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families and subjected to harsh conditions, cultural suppression, and abuse. The schools sought to erase Indigenous languages, cultures, and traditions, contributing to a profound loss of identity among the students.

- High Mortality Rates and Poor Conditions: The residential schools were often characterized by overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, leading to high mortality rates among students. Diseases such as tuberculosis were widespread, and there were instances of neglect, malnutrition, and physical abuse.

- Unmarked Graves: Many children who died at these schools were buried in unmarked graves, and the circumstances of their deaths were often undocumented. In some cases, families were not informed of the deaths, and the children’s identities were lost over time.

- Discovery of Graves (Recent Years): In recent years, through the efforts of Indigenous communities, survivors, and the work of various organizations, there have been discoveries of unmarked graves near former residential school sites. These findings have brought attention to the extent of the tragedy and the unacknowledged loss of life.

- Involvement of Missionaries and Religious Organizations: Missionaries and religious organizations played a significant role in the operation of residential schools. Various Christian denominations, including the Catholic Church, Anglican Church, United Church of Canada, and others, were involved. The involvement of these institutions in the administration of the schools has led to calls for accountability and acknowledgment of the role they played in the suffering experienced by Indigenous children.

- Impact on Indigenous Communities: The discovery of these unmarked graves has had a profound impact on Indigenous communities, rekindling trauma and sorrow. It has sparked a national and international conversation about the historical and ongoing impact of colonization and the need for reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.

In response to these discoveries, there have been calls for accountability, justice, and efforts to address the legacy of the residential school system. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Canada has documented the experiences of survivors and made recommendations to promote healing and reconciliation. The events surrounding the unmarked graves underscore the importance of acknowledging and addressing the historical injustices committed against Indigenous peoples in Canada. The Canadian government has taken several steps to acknowledge the historical injustices and address the impacts of the residential school system on Indigenous peoples. However, as of my last knowledge update in January 2022, specific reparations have been limited, and the process of reconciliation is ongoing. Here are some key developments:

- Apologies: Various Canadian Prime Ministers and government officials have issued formal apologies for the role of the Canadian government in the establishment and operation of residential schools. Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an apology in 2008, and subsequent leaders, including Justin Trudeau, have reiterated the apology and committed to reconciliation efforts.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC): The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in 2008 to document the experiences of survivors of residential schools, educate the public about the history and legacy of these schools, and make recommendations for reconciliation. The TRC concluded its work in 2015 and produced a report with 94 Calls to Action.

- Compensation and Settlements: Various legal settlements and compensation programs have been established to address specific aspects of the harm caused by residential schools. For example, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) in 2007 included the Common Experience Payment for eligible survivors and the Independent Assessment Process for claims of abuse.

- Investigations and Searches for Unmarked Graves: The Canadian government has provided funding for investigations into unmarked graves near former residential school sites. These efforts have led to the discovery of unmarked graves, bringing attention to the loss of life and prompting discussions about commemoration and memorialization.

- Reconciliation Initiatives: Beyond financial reparations, there have been ongoing efforts to promote reconciliation and healing. This includes funding for cultural revitalization projects, support for Indigenous languages, and initiatives aimed at addressing socioeconomic disparities.

It is crucial to note that the process of acknowledging the damage caused by residential schools and working towards reconciliation is ongoing. The discoveries of unmarked graves have intensified discussions around the need for further actions, accountability, and justice. Efforts continue to address the Calls to Action from the TRC and to involve Indigenous communities in shaping the path forward. Reparations and reconciliation are complex processes that involve multiple stakeholders, including the Canadian government, Indigenous leaders, and non-Indigenous Canadians. It’s recommended to consult the latest sources for updates on government actions and Indigenous perspectives on these issues.

Photo Top: The First Nations Ancestral Burial Ground with a ceremonial ritual in progress.

Photo Bottom: A First Nations protest against commercial development of sacred, tribal land, in an attempt to treat the grounds with respect and the land to be returned.

The Progressive Social Degeneration of the First Nations based on Childhood Experiences

There is evidence to suggest that the traumatic experiences associated with the residential school system in Canada, along with other historical and ongoing challenges, have contributed to higher rates of alcoholism and drug addiction among some Indigenous peoples, including First Nations. It’s important to approach this topic with sensitivity and an understanding of the complex factors involved.

The residential school system, which operated from the 19th century until the latter half of the 20th century, involved the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their families, cultural suppression, abuse, and the denial of their languages and traditions. Many survivors of these schools experienced profound trauma that has had intergenerational effects. Several factors may contribute to higher rates of alcoholism and drug addiction within Indigenous communities:

- Intergenerational Trauma: Trauma experienced by individuals in the residential school system has been passed down through generations, impacting the mental health and well-being of descendants. Intergenerational trauma can contribute to coping mechanisms such as substance abuse.

- Cultural Disruption: The suppression of Indigenous cultures, languages, and traditions in the residential schools disrupted the transmission of cultural knowledge and practices. Reconnecting with cultural identity can be a crucial aspect of healing, and the loss of cultural continuity may contribute to challenges in mental health and substance use.

- Socioeconomic Disparities: Many Indigenous communities face socioeconomic challenges, including inadequate housing, limited access to education and healthcare, and high rates of unemployment. These disparities can contribute to stressors that may lead to substance abuse as a coping mechanism.

- Lack of Mental Health Services: Limited access to culturally appropriate mental health services in some Indigenous communities can be a barrier to addressing trauma-related issues. Substance abuse may sometimes be a way, individuals cope with untreated mental health challenges.

- Colonisation and Discrimination: Ongoing impacts of colonisation, systemic discrimination, and historical injustices contribute to a complex set of factors that affect the well-being of Indigenous individuals and communities.

Efforts are underway to address these challenges, including initiatives focused on mental health, addiction treatment, cultural revitalisation, and community-based healing. It’s important to recognise the resilience and strength within Indigenous communities and the importance of self-determination in developing solutions to address these complex issues. Additionally, acknowledging and respecting the perspectives and experiences of Indigenous peoples is crucial in fostering understanding and support for healing processes.

The Impact of British, colonial imperialism as the root cause of suffering of the First Nations.

The suffering of Indigenous peoples in Canada, including the First Nations, has complex roots, and it cannot be attributed solely to one cause. However, the impacts of colonialism and British imperial policies have played a significant role in shaping the historical and contemporary challenges faced by Indigenous communities. Here are some key points:

- Colonial Policies: British colonial policies in Canada, including the establishment of the residential school system and the signing of treaties, have had lasting effects on Indigenous communities. The imposition of European systems of governance, land dispossession, and attempts to assimilate Indigenous cultures into Euro-Canadian norms contributed to the disruption of traditional ways of life.

- Residential Schools: The residential school system, which operated with the collaboration of the Canadian government and various Christian denominations, including the Catholic Church, aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into European culture. The traumatic experiences in these schools, including cultural suppression, abuse, and neglect, had profound and lasting effects on Indigenous individuals and communities.

- Land Dispossession: Indigenous peoples in Canada experienced the loss of their traditional lands through a combination of colonial policies, treaties, and encroachment by settlers. This had significant implications for Indigenous ways of life, economies, and cultural practices.

- Intergenerational Trauma: The trauma experienced by Indigenous individuals, including the legacy of the residential school system, has been passed down through generations, contributing to what is known as intergenerational trauma. This trauma can manifest in various forms, impacting mental health, social structures, and community well-being.

- Ongoing Challenges: The impacts of historical colonial policies continue to affect Indigenous communities today. Socioeconomic disparities, inadequate access to healthcare and education, and discrimination are among the ongoing challenges faced by Indigenous peoples in Canada.

While colonialism, including British colonialism, played a crucial role in shaping the historical context, it is important to recognise that the issues faced by Indigenous peoples are multifaceted and involve complex interactions with various historical, social, and economic factors. Contemporary efforts toward reconciliation, acknowledging historical injustices, and supporting Indigenous self-determination are crucial steps in addressing the legacy of colonialism and promoting a more equitable and just society. The Indigenous population in Canada, which, according to some social anthropologists, includes First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, was estimated to be around 1.7 million individuals. However, it is important to note that population figures can change, and the most up-to-date information can be obtained from official sources, such as Statistics Canada.[26]

The distribution of the Indigenous population in Canada is diverse, and not all Indigenous individuals reside on reserves. Many live, in urban areas, towns, and cities across the country. Reserves are specific areas of land set aside for the use and benefit of First Nations communities, but not all Indigenous people live on reserves. Some reside in rural or urban settings, contributing to the overall diversity of the Indigenous population in Canada. As for the comparison between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations in Canada, the Indigenous population represents a minority within the broader Canadian population. The majority of Canadians are non-Indigenous, and the Indigenous population is distributed across the country, with varying degrees of concentration in different regions. However, Canada 2023 population is estimated at 38,781,291 people at mid-year. Canada population is equivalent to 0.48% of the total world population. Canada ranks number 38 in the list of countries (and dependencies) by population.[27]

Literacy and the First Nations

Literacy rates can vary among different First Nations communities, and it’s important to consider various factors that contribute to educational outcomes. Historically, Indigenous communities, including First Nations, have faced challenges in accessing quality education due to various factors such as inadequate resources, cultural insensitivity in educational approaches, and geographic isolation. However, there have been efforts at the government and community levels to address these challenges and improve educational outcomes for Indigenous students. Some of these initiatives include:

- Investment in Education: The Canadian government has made efforts to increase funding for Indigenous education, aiming to improve infrastructure, resources, and educational programming. Investments are intended to address the historical underfunding of Indigenous education and contribute to better learning outcomes.

- Language and Cultural Education: Recognizing the importance of preserving Indigenous languages and cultures, there are initiatives to incorporate Indigenous languages and cultural content into educational curricula. This helps to make education more culturally relevant and responsive to the needs of Indigenous students.

- Community Engagement and Self-Determination: Collaborative efforts involve engagement with Indigenous communities to ensure that education is designed in a way that respects and reflects their unique needs and perspectives. Supporting Indigenous self-determination in education is seen as crucial for success.

- Post-Secondary Education Support: There are various programs and initiatives to support Indigenous students in pursuing post-secondary education, including scholarships, grants, and mentorship programs. These initiatives aim to address barriers to higher education faced by Indigenous individuals.

- Reconciliation and Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC): The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Canada has highlighted the importance of education in the reconciliation process. The TRC’s Calls to Action include recommendations related to education, emphasizing the need for curriculum changes, teacher training, and support for Indigenous-controlled education.

While progress is being made, challenges persist, and more work is needed to ensure equitable and culturally responsive education for Indigenous communities.

General Activities of the First Nations

First Nations individuals in Canada, like any diverse population, engage in a wide range of activities and professions. It is important to recognise the diversity of skills, talents, and interests within Indigenous communities. While there is no single narrative that captures all experiences, here are some common activities and professions in which First Nations individuals may be engaged, both in Canada and globally:

- Traditional Activities: Many First Nations individuals actively participate in traditional activities that connect them to their cultural heritage. This includes practices such as hunting, fishing, trapping, and gathering, which may be essential for subsistence, cultural preservation, and spiritual connection to the land.

- Arts and Culture: First Nations individuals contribute significantly to the arts and culture scene. This includes traditional arts such as beadwork, carving, and storytelling, as well as contemporary expressions through visual arts, literature, film, and music.

- Education: First Nations individuals are involved in various aspects of the education sector, including teaching, administration, and curriculum development. Efforts are made to incorporate Indigenous perspectives into educational programs to better reflect the diverse history and culture of Indigenous peoples.

- Healthcare: Some First Nations individuals work in healthcare professions, including nursing, medicine, counseling, and community health services. Addressing healthcare disparities and promoting culturally sensitive healthcare practices are priorities in many Indigenous communities.

- Public Service and Governance: Many First Nations individuals are involved in public service and governance, serving in leadership roles within their communities, tribal councils, and participating in municipal, provincial, and federal government structures.

- Business and Entrepreneurship: There is a growing presence of First Nations individuals in business and entrepreneurship. This includes owning and operating businesses in various sectors, such as tourism, agriculture, and technology.

- Environmental and Land Stewardship: Indigenous peoples, including First Nations, often play a crucial role in environmental and land stewardship. Many communities are actively engaged in sustainable resource management, land conservation, and addressing environmental challenges.

Globally, Indigenous peoples, including those who identify as First Nations, may be involved in similar activities and professions, contributing to their communities and societies in diverse ways. It’s important to recognise the richness and diversity of Indigenous cultures and the ways in which individuals engage with their communities and the broader world.

The Impact of the First Nations on Canadians and Globally, in recent years

First Nations in Canada, like Indigenous peoples around the world, have had significant impacts on Canadian society and have contributed to global discussions on issues such as Indigenous rights, environmental stewardship, and cultural diversity. Here are some key areas where First Nations have made an impact in recent years:

- Advocacy for Indigenous Rights: First Nations individuals and communities have been at the forefront of advocating for the recognition and protection of Indigenous rights. This includes efforts to address historical injustices, promote self-determination, and assert treaty rights.

- Land and Environmental Stewardship: Indigenous communities, including First Nations, have been leaders in advocating for environmental sustainability and responsible land stewardship. Many Indigenous groups actively engage in discussions and actions related to climate change, resource management, and protecting biodiversity.

- Reconciliation Efforts: In Canada, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) has played a crucial role in addressing the historical impacts of the residential school system. First Nations individuals and communities have been actively involved in reconciliation efforts, contributing to national conversations about acknowledging historical wrongs and building better relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- Cultural Contributions: First Nations individuals have made significant contributions to Canadian and global culture, including art, literature, music, and film. Indigenous voices and perspectives are increasingly recognized and celebrated, contributing to a more inclusive and diverse cultural landscape.

- Legal Challenges and Achievements: First Nations have been involved in legal challenges aimed at upholding Indigenous rights and addressing issues such as land claims and resource development. Landmark legal cases have had implications not only for Indigenous communities in Canada but also for the broader understanding of Indigenous rights and title.

- Economic Development: Indigenous economic development, including entrepreneurship and business ventures, has been on the rise. First Nations individuals and communities are increasingly involved in economic initiatives that contribute to sustainable development and community well-being.

- Representation in Politics and Leadership: First Nations individuals have been elected to various levels of government, contributing to the political landscape of Canada. Indigenous leaders advocate for policies that address the needs and aspirations of their communities.

- Global Indigenous Solidarity: First Nations individuals and organisations actively participate in global Indigenous movements and solidarity efforts. This includes collaborations with Indigenous groups from other countries to address common challenges and share experiences.

While progress has been made, challenges persist, and the impact of historical injustices continues to be felt. The ongoing efforts of First Nations individuals and communities contribute to a broader global dialogue on Indigenous rights, environmental sustainability, and the importance of diverse cultural perspectives.

Climate Degradation and the Global Impact made on its arrest by the First Nations

The First Nations of Canada have become vocal advocates in the fight against climate change, even though their contribution to climate change has been very small. The key strategies regarding their role and impact:

- First Nations people are on the frontlines of experiencing severe climate change effects in Canada – including coastal erosion, melting permafrost compromising infrastructure, risks of losing entire villages to rising sea levels, decline in wildlife/vegetation central to diet and culture, etc.

- Indigenous voices have drawn widespread attention to the disproportionate impact of climate crisis on their communities and way of life at international summits and calls for action. Global awareness of threats to First Nations has boosted motivation for change.

- Some First Nations activists and leaders, like Melina Laboucan-Massimo[28], have taken influential roles in global climate organizations like Greenpeace to spotlight indigenous perspectives. Their urgency and moral voice resonates widely.

- First Nations legal challenges and protests against major oil/gas developments have fuelled the climate movement locally and inspired others globally about assertive grassroots mobilisation to demand government action. Cases like the Trans Mountain pipeline lawsuit have symbolic impact.

- First Nations traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable land stewardship practices are now being recognised internationally as valuable climate mitigation and adaptation solutions the world can apply more broadly.

While contributing little to historic emissions, First Nations face possibly the most severe climate consequences worldwide threatening their cultural survival. By sharing their plight and knowledge globally, they have become a moral force advocating for ambitious targets and conservation – spurring awareness and policy changes benefiting the whole planet.

The First Nations and the Canadian Parliament

There are Indigenous Members of Parliament (MPs), including some who are First Nations, representing various constituencies in the Canadian Parliament. The number of Indigenous MPs can vary from one election to another, and it’s important to check the most recent information for the current composition of Parliament. In Canada, Indigenous representation in federal, provincial, and territorial governments has been increasing, reflecting a growing awareness of the importance of diverse perspectives in political decision-making. Indigenous MPs, including those who are First Nations, contribute to discussions on a wide range of issues, including Indigenous rights, economic development, environmental protection, and social justice.

The Unique Traditions and Religious beliefs of the First Nations

The First Nations in Canada encompass diverse cultural groups, each with its unique traditions, languages, and spiritual beliefs. It’s important to recognize that there is no single set of beliefs or practices that represents all First Nations, as each nation has its own distinct cultural identity. However, I can provide a general overview of some common elements found in the traditions and spiritual beliefs of various First Nations:

- Sacred Ceremonies: Many First Nations practice sacred ceremonies that are central to their spiritual beliefs. These ceremonies often involve rituals, dances, songs, and the use of sacred items. Examples include the Sun Dance, Sweat Lodge ceremonies, and Potlatch ceremonies. However, the 1885 to 1951 ban has led to a patriarchal culture where women are excluded from leadership.[29]

- Connection to Nature: A common theme among many First Nations is a deep connection to the natural world. The land, animals, plants, and elements are often viewed as sacred, and there are spiritual practices that honor and seek harmony with the environment.

- Oral Traditions: Oral traditions play a crucial role in preserving cultural knowledge, history, and spiritual teachings. Stories, myths, and legends are passed down through generations, serving as a means of education and connection to the cultural and spiritual heritage.

- Spirituality and Animism: Many First Nations communities have spiritual beliefs that include animism, the idea that all things, including animals, plants, and natural elements, possess a spiritual essence. There is often a belief in a spiritual interconnectedness that binds all living things.

- Dreaming and Vision Quests: Vision quests are spiritual journeys undertaken by individuals seeking guidance, insight, or a connection with the spiritual realm. These quests often involve fasting, meditation, and time spent alone in nature. Dreams and visions hold significant spiritual meaning.

- Totem Poles: Totem poles are traditional carved wooden structures that are rich in symbolism and often represent family lineages, stories, and spiritual beings. Different figures on a totem pole can convey a range of meanings related to cultural identity and spirituality.

- Medicine Wheel: The Medicine Wheel is a symbolic and spiritual concept used by some First Nations. It often represents the interconnectedness of various aspects of life, including the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual dimensions.

- Shamanism and Healing Practices: Some First Nations traditions include shamanic practices and healing ceremonies. Traditional healers may use herbs, rituals, and spiritual practices to promote physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being.

It’s essential to approach discussions about First Nations traditions and spiritual beliefs with respect for the diversity among Indigenous communities. The richness of these traditions contributes to the cultural tapestry of Canada and underscores the importance of recognising and preserving Indigenous knowledge and heritage.

The First Nation Tribes and Leaders

“First Nations” in Canada encompasses a diverse range of Indigenous peoples, each with its own distinct cultures, languages, and histories. There are over 600 recognized First Nations in Canada, and within these nations, there are numerous tribes, bands, and clans. Each First Nation has its own governance structure, leadership, and traditions. It’s important to recognize the richness and diversity of these communities. Below, I’ll mention a few examples of prominent First Nations and their leaders, acknowledging that this is not an exhaustive list:

Ojibwe (Anishinaabe):[30]

- The Ojibwe people are part of the Anishinaabe cultural group.

- Traditional territory includes areas in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and parts of the United States.

- Leaders and chiefs within Ojibwe communities often play crucial roles in decision-making and cultural preservation.

Cree[31]:

- The Cree are one of the largest First Nations groups in Canada.

- They have a broad traditional territory covering parts of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and the Northwest Territories.

- Cree leadership structures may include chiefs and councils representing individual communities.

Haida[32]:

- The Haida Nation is an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast.

- Traditional territory includes Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) in British Columbia.

- The Haida have hereditary chiefs and matriarchs who play key roles in governance and cultural preservation.

Mi’kmaq[33]:

- The Mi’kmaq are an Indigenous people in the Atlantic region.

- Traditional territory includes parts of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland.

Mi’kmaq governance may involve chiefs and councils representing various communities.

Salish[34]:

- The Salish people are found in the Pacific Northwest and have various subgroups, including the Coast Salish and Interior Salish.

- Traditional territory spans parts of British Columbia, Washington, and Montana.

- Leadership structures may include hereditary chiefs and elected officials.

Dene[35]:

- The Dene people are Indigenous to the northern parts of Canada.

- Traditional territory includes regions in the Northwest Territories, Yukon, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

- Dene communities may have chiefs and councils involved in governance.

Inuit[36]:

- The Inuit are Indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions.

- There are eight main Inuit ethnic groups

- Traditional territory includes Nunavut, Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Nunavik, and Nunatsiavut.

- Inuit governance often involves various levels of representation, including Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami at the national level.

Leadership within First Nations communities can take various forms, including hereditary chiefs, elected chiefs and councils, and other governance structures. It’s important to note that each community has its own unique traditions and practices regarding leadership and decision-making. Additionally, the recognition of leadership roles may vary among different First Nations.

The Iconic First Nations Traditional Healers: Medicine Man[37]

Many First Nations communities in Canada have individuals with traditional healing knowledge and practices, often referred to as “medicine people,” “medicine men,” “shamans,” or “faith healers.” These individuals play important roles in the spiritual and physical well-being of their communities. It’s important to note that the terms used to describe these individuals can vary among different Indigenous cultures.

Roles and Practices:

- Healing: Traditional healers often use a combination of herbal remedies, rituals, ceremonies, and spiritual practices to address physical, emotional, and spiritual ailments.

- Spiritual Guidance: They may provide spiritual guidance, conduct ceremonies, and help individuals connect with their cultural and spiritual roots.

- Ceremonies: Many traditional healing practices involve ceremonies that are designed to restore balance and harmony within the individual and the community.

- Cultural Preservation: Traditional healers often play a role in preserving and passing on cultural knowledge, including traditional healing methods, to the next generation.

Cultural Diversity:

- The specific practices and roles of traditional healers vary widely among different First Nations cultures. What is considered appropriate or effective may differ from one community to another.

Integration with Western Medicine:

- In some cases, traditional healing practices may be integrated with Western medicine. Many Indigenous communities recognize the value of both traditional and modern approaches to health and well-being.

Respect and Sensitivity:

- It is crucial to approach discussions about traditional healing with respect for cultural diversity and sensitivity. Traditional healing practices are deeply tied to cultural identity and should be understood within their specific cultural contexts.

Continued Importance:

- Traditional healing practices continue to be valued and respected within many First Nations communities, providing a holistic approach to health that incorporates spiritual, emotional, and physical well-being.

It is important to recognise that the diversity of First Nations cultures means that practices can vary widely from one community to another. Additionally, the terminology used to describe traditional healers may differ among Indigenous peoples. Understanding and respecting these cultural nuances is essential when discussing traditional healing within the context of Indigenous communities.

Major battles between the First Nation Tribes and Canadians or British, in the past[38]

There were significant conflicts and battles between various First Nations tribes and Indigenous groups in Canada and the European colonizers, including the British and later the Canadians. These conflicts spanned a considerable period and were influenced by factors such as land disputes, cultural differences, economic interests, and attempts to assert control over territories. Some notable conflicts include:

Pontiac’s War (1763-1766):[39]

- Pontiac’s War was a conflict between a confederation of Indigenous tribes led by Chief Pontiac, primarily from the Great Lakes region, and British forces. It followed the end of the French and Indian War. The war was characterized by a series of attacks on British forts and settlements in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region.

War of 1812 (1812-1814):[40]

- The War of 1812 involved conflicts between British and Canadian forces, including Indigenous allies, against American forces. Indigenous nations, such as the Shawnee under Tecumseh, played significant roles in battles like the Battle of Tippecanoe and the Battle of Queenston Heights.

Red River Resistance (1869-1870):[41]

- The Red River Resistance involved the Métis people, led by Louis Riel, resisting the transfer of the Hudson’s Bay Company territory to the Dominion of Canada. The Métis and their Indigenous allies engaged in armed conflict with Canadian forces, leading to the establishment of the province of Manitoba.

North-West Rebellion (1885):[42]

- The North-West Rebellion, also known as the Métis Resistance, involved the Métis people, led by Louis Riel, and some First Nations groups, such as the Cree, resisting Canadian government policies and encroachments on their lands. The conflict included battles such as the Battle of Duck Lake and the Battle of Batoche.

Chilcotin War (1864):[43]

- The Chilcotin War was an armed conflict in the interior of British Columbia between a group of Tsilhqot’in (Chilcotin) people and a road-building crew of predominantly non-Indigenous workers. It was sparked by tensions over the construction of the Bute Inlet road and resulted in the deaths of a number of road crew members.

It is essential to note that these conflicts were complex and multifaceted, involving various Indigenous nations, groups, and leaders with distinct goals and motivations. The outcomes of these conflicts varied, and they had lasting impacts on the relationships between Indigenous peoples and the colonial and later Canadian governments. These historical events are an integral part of the broader narrative of Indigenous history and the complex interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in Canada.

First Nations Tribes have a Council or Leader[44]

There is no single council or leader that represents all First Nations in Canada. Instead, each First Nation operates autonomously, with its own governance structure and leadership. The diversity of First Nations is reflected in the variety of governance models, traditional systems, and contemporary leadership structures that exist across different communities. Key points to consider:

- Autonomous Nations: Each First Nation is considered a distinct and autonomous nation with its own government and leadership. The concept of self-determination is crucial, allowing each community to determine its own governance structure and decision-making processes.

- Chief and Council: Many First Nations in Canada have an elected Chief and Council system. The Chief is often the leader or head of the community, and the Council is composed of elected representatives. The roles and responsibilities of the Chief and Council can vary among different First Nations.

- Hereditary Chiefs: Some First Nations, especially those on the West Coast, have hereditary chief systems where leadership is passed down through family lines. Hereditary chiefs may play a significant role in decision-making and governance.

- Tribal Councils: Some First Nations choose to form regional or tribal councils to address common issues and collaborate on matters of mutual interest. Tribal councils are composed of representatives from member First Nations.

- National and Regional Organizations: National and regional Indigenous organizations exist to address broader issues and advocate for the rights and interests of First Nations peoples. The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is a national organization that represents First Nations at the national level.

- Treaty Organizations: In the context of historic treaties, some First Nations are part of treaty organizations that represent their interests in negotiations and implementation of treaties with the Crown.

It is important to recognize the diversity of governance structures and leadership models among First Nations. Each community has its own traditions, customs, and methods of decision-making that are grounded in their unique histories and cultures. The recognition of this diversity is a fundamental aspect of respecting the autonomy and self-determination of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

First Nations Treaties from the past with the applicable Canadian Government[45]

The historical treaties between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian government were agreements made between the 18th and 20th centuries. These treaties were intended to define the relationships between the Indigenous nations and the Crown, often addressing issues such as land rights, resource sharing, and other matters. Here are some key treaties:

Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1760-1761):

- This treaty was signed primarily between the British Crown and the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet peoples in the Maritimes. It was aimed at maintaining peace and fostering a cooperative relationship.

Royal Proclamation of 1763:

- While not a treaty in itself, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a foundational document that set out guidelines for relationships between the Crown and Indigenous peoples. It recognized Indigenous land rights and established a process for acquiring Indigenous lands.

Treaty No. 1 (1871):

- Also known as the Stone Fort Treaty, this treaty was signed between the OjibwaSwampy Cree Nations and the Canadian government. It covered areas in what is now Manitoba.

No. 2 (1871):

- This treaty was signed between the Ojibwa and Swampy Cree Nations and the Canadian government, covering areas in what is now Manitoba.

Treaty No. 3 (1873):

- Also known as the Northwest Angle Treaty, this treaty was signed between the Saulteaux and Swampy Cree Nations and the Canadian government. It covers areas in what is now Ontario and Manitoba.

Treaty No. 4 (1874):

- This treaty was signed between the Cree and Saulteaux Nations and the Canadian government. It covers areas in what is now Saskatchewan.

Treaty No. 5 (1875):

- This treaty was signed between the Ojibwa and Swampy Cree Nations and the Canadian government. It covers areas in what is now Manitoba and parts of Ontario and Saskatchewan.

Treaty No. 6 (1876):

- This treaty was signed between the Plains and Woods Cree and the Canadian government, covering areas in what is now Alberta, Saskatchewan, and parts of Manitoba.

Treaty No. 7 (1877):

- This treaty was signed between the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Stoney, and the Canadian government. It covers areas in what is now Alberta.

Treaty No. 8 (1899):

- This treaty was signed between the Dene and Cree nations and the Canadian government. It covers areas in what is now Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and parts of the Northwest Territories.

Treaty No. 9 (1905-1906):

- Also known as the James Bay Treaty, this treaty was signed between the Ojibwa, Cree, and Oji-Cree Nations and the Canadian government. It covers areas in northern Ontario.

Treaty No. 10 (1906-1907):

- This treaty was signed between the Dene and Cree Nations and the Canadian government, covering areas in what is now Saskatchewan and parts of Alberta.

Treaty No. 11 (1921):

- This treaty was signed between the Dene and Cree Nations and the Canadian government. It covers areas in what is now the Northwest Territories and parts of Yukon.

It is essential to note that the interpretation and implementation of these treaties have been subjects of ongoing discussions, negotiations, and legal challenges. The treaties form a significant part of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian government, and their impact continues to be felt in contemporary discussions about Indigenous rights and land claims.

The Practice of Scalping amongst the First Nations[46]

The practice of “scalping” has been historically associated with certain Indigenous tribes and European colonizers during periods of conflict in North America. However, it’s important to note that not all Indigenous peoples engaged in scalping, and the practice should not be generalized across all First Nations. The term “scalping” refers to the act of removing a person’s scalp, which includes the skin and hair on the head. Historically, it has been documented among various groups in different parts of the world, but it gained particular attention in North America during the colonial period. Factors and considerations related to scalping include:

Warfare Practices:

- Scalping was, in some instances, associated with acts of warfare between Indigenous tribes and European settlers or rival Indigenous groups. The motivations and circumstances varied widely.

Cultural Variation:

- Practices related to warfare, including treatment of captives, varied significantly among different Indigenous tribes. What was true for one group may not have been true for another.

European Influence:

- It is worth noting that there are historical accounts suggesting that European colonisers also engaged in scalping, and the practice was not exclusive to Indigenous peoples.

Stereotypes and Misconceptions:

- Stereotypes and misconceptions about scalping have been perpetuated, contributing to negative portrayals of Indigenous peoples. It is essential to approach historical accounts with a critical and nuanced perspective.

Cultural Practices:

- Indigenous cultures across North America have rich and diverse traditions, and warfare was just one aspect of their histories. It is important to avoid reducing complex cultures to a single, sensationalised practice.

Understanding historical practices, including those related to conflict, requires careful consideration of the specific cultural contexts and individual circumstances. Additionally, it is crucial to recognize that Indigenous cultures are not static and have evolved over time. Discussions about historical practices should be approached with sensitivity and a commitment to dispelling stereotypes and misconceptions.

The Extinction of Bisons[47]

The relationship between Indigenous peoples and bison in North America is complex, and multiple factors contributed to the decline in bison populations. Both Indigenous peoples and European settlers played roles in the changes that occurred. Plains bison were extirpated from Canada by 1888. The wood bisons were fewer and following several severe winters in the late 1800s, their population reached a low of about 200.

Indigenous Peoples and Bison:

- Historically, many Indigenous peoples on the Great Plains relied on bison as a primary source of food, clothing, and materials for tools and shelter.

- Bison hunting was a sustainable practice for Indigenous communities, with tribes utilizing various parts of the bison, minimizing waste.

European Settlement and Overhunting:

- The arrival of European settlers in North America brought significant changes to the relationship between Indigenous peoples and bison.

- European settlers engaged in large-scale, market-driven bison hunting, driven by the fur and hide trade. This contributed to overhunting and a significant decline in bison populations.

Disruption of Bison Ecosystem:

- European settlers disrupted the natural bison ecosystem through habitat destruction, introduction of livestock, and changes in fire regimes. These factors contributed to the decline of the vast bison herds that once roamed the Great Plains.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples:

- The depletion of bison populations had profound consequences for Indigenous peoples who depended on them. Loss of the primary food source led to cultural, economic, and social challenges for many tribes. This lack of protein source was considered as the principal cause for the development of pulmonary tuberculosis in the First Nations[48]

Introduction of Disease:

- The introduction of diseases, such as bovine tuberculosis and anthrax, from European livestock to bison herds had negative impacts on both bison populations and the Indigenous communities that relied on them. These diseases affected not only the bison but also the health of the people who depended on them for sustenance.

It is important to recognise that the bison population decline was driven by a combination of factors, including overhunting, habitat disruption, and the introduction of diseases. The impact on Indigenous peoples was significant, as their traditional way of life was disrupted, and they faced challenges in adapting to the changes brought by European colonisation. Efforts have been made in recent times to restore and conserve bison populations, recognizing their ecological importance and cultural significance for Indigenous peoples. Conservation initiatives, such as the reintroduction of bison to protected areas, aim to contribute to the restoration of these iconic animals and their roles in the ecosystems of North America

Disease and cause of Death amongst the First nations in the past and in the 21st century[49]

In the past, the introduction of infectious diseases by European settlers had a devastating impact on Indigenous populations in the Americas, including First Nations. The lack of immunity to these diseases resulted in widespread outbreaks that caused significant loss of life. Smallpox, measles, influenza, and other infectious diseases had particularly severe consequences. These diseases were major causes of death, leading to population declines and affecting the social fabric of Indigenous communities.

In the 21st century, while infectious diseases remain a concern, other health challenges have emerged, often linked to social, economic, and environmental factors. Some of the major health issues faced by First Nations in the contemporary era include:

Chronic Diseases:

- Diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory diseases are significant health challenges for Indigenous communities. Lifestyle factors, diet, and limited access to healthcare can contribute to the prevalence of chronic diseases.

Mental Health Issues:

- Mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are of concern. Historical traumas, colonization, and social inequalities contribute to the high prevalence of mental health challenges.

Substance Abuse:

- Substance abuse, including alcohol and drug abuse, can be linked to various social and economic factors, including historical trauma, poverty, and limited access to resources.

Access to Healthcare:

- Limited access to quality healthcare services remains a challenge for some Indigenous communities, particularly those in remote or rural areas. Barriers to healthcare access can impact health outcomes.

Environmental Health:

- Environmental factors, such as inadequate housing, water quality issues, and exposure to environmental contaminants, can impact the health of Indigenous communities.

Suicide Rates: