Sixty Years of ‘Dr. Strangelove’: A Nuclear War Planner on the Nightmare Comedy

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, 29 Jan 2024

Kevin Gosztola | The Wide Shot – TRANSCEND Media Service

The nightmare comedy in Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece remains as razor-sharp as ever with the Doomsday Clock at 90 seconds to midnight.

24 Jan 2024 – The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists kept the Doomsday Clock at 90 seconds to midnight for 2024, signaling that the world remains closer than ever before to catastrophe. China, Russia, and the United States, the three largest nuclear powers, have essentially allowed agreements for arms control to collapse and are fueling a 21st century arms race to modernize their nuclear arsenals.

Since 1947, the group of scientific and technological experts has gauged global threats through the Doomsday Clock. It was first set at seven minutes to midnight. U.S. and Soviet Union bomb tests pushed the Bulletin to move the clock forward to two minutes to midnight in 1953. But a decade later, the clock was moved to 12 minutes to midnight after the U.S. and Soviet Union signed a treaty limiting some atmospheric nuclear testing.

The Cuban missile crisis greatly intensified the threat of nuclear annihilation in 1962 and unfolded while director Stanley Kubrick was producing his masterpiece, “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.”

Kubrick’s classic satirical film starring Sterling Hayden, George C. Scott, Slim Pickens, James Earl Jones, Tracy Reed, and Peter Sellers (in three roles) marks its sixtieth anniversary this year. It was released on January 29, 1964.

Back in 2017, I spoke to Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg about his book, “The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner.”

While Ellsberg was primarily known for exposing several of the lies that the U.S. military told about the Vietnam War, he also worked as a nuclear war planner for the RAND Corporation (the BLAND Corporation in “Dr. Strangelove”). He had access to the highest levels of the U.S. military and knew Herman Kahn, who developed the concept for the “Doomsday Machine” that director Stanley Kubrick borrowed for his film.

Ellsberg spent an entire chapter of his book on what he labeled the “Strangelove Paradox.” He also recalled the first time that he saw “Dr. Strangelove” in 1964 and how it left him “dumbstruck by the realism.”

“Harry Rowen and I had gone into D.C. from the Pentagon during the workday to see it, ‘for professional reasons.’ We came out in the afternoon sunlight, dazed by the light and the film, both agreeing that what we had just seen was, essentially, a documentary,” Ellsberg wrote.

“How, I wondered, had the filmmakers picked up such an esoteric, highly secret (and totally incredible) detail as the lack of a Stop code, and the alleged reason for it? Or, for that matter, the real lack of any physical restraint on the ability of a squadron commander, or even a bomber pilot, to execute an attack without presidential authorization?”

‘War Is too Important to Be Left to Politicians’

As Ellsberg said during our interview, “In that movie, a rogue general sends off planes [to attack the Soviet Union], and the president has no way to call them back. Nothing that happened in between their takeoff and their dropping their [nuclear] weapons could actually change their operations.”

“There was no way to tell them either that the enemy had surrendered or there had been a terrible mistake at the beginning that had led to their launch — a false alarm. Or a change of mind by the president,” Ellsberg added.

The bomber pilots in “Dr. Strangelove,” led by cowboy Major King Kong (Pickens), open an envelope from Strategic Air Command (SAC) that contains “Plan R.” It is a top secret plan for a nuclear strike. The pilots follow instructions, silence their radio, and set a code receiver to block transmissions to ensure that the Soviets cannot sabotage them.

According to Ellsberg’s book, this was a stunningly accurate depiction of the envelope authentication procedures that were used. In 1959, he found out that the U.S. Pacific Air Forces had only one envelope with only one card. That card contained a “Go” code for executing a strike. “There was no stop or return code in the envelope or otherwise in the possession of the plane crew.”

If an “Execute” order was received, the procedure was designed to ensure that no official, not even the president of the United States, would be able to reverse course. More importantly, as early as 1960, Ellsberg became aware that no “Stop” code was included to prevent the Soviet Union from discovering the code and “misdirect[ing] the whole force back.”

General Jack Ripper (Hayden), the maniac commanding officer who orders the nuclear attack, takes a number of outlandish steps (e.g. impounding all radios) to make certain the Soviet Union does not get in the way of his crusade. The steps he takes also make it impossible for officers higher in the chain of command to stop him.

The general shares his belief that “war is too important to be left to politicians” through a rant that concludes with one of the nightmare comedy’s best known lines.

“[Politicians] have neither the time, the training, nor the inclination for strategic thought. I can no longer sit back and allow communist infiltration, communist indoctrination, communist subversion and the international communist conspiracy to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids,” Ripper proclaims.

Ripper’s derangement is comedy gold, but it also reflected the widespread sentiment among military officers that a “civilian president” might lack the fortitude or grit to retaliate if Washington, D.C., was attacked by the Soviet Union. Or, as Ellsberg’s book mentioned, a president might squander an opportunity to mount a “coordinated surprise attack.”

This mindset is represented in one of several scenes in the magnificent War Room that Kubrick had built for the film. General Buck Turgidson (Scott) makes the case for a broader nuclear attack to prevent the Soviets from responding to the strike launched by Ripper.

“Mr. President, we are rapidly approaching a moment of truth both for ourselves as human beings and for the life of our nation,” Turgidson declares. “Now, truth is not always a pleasant thing. But it is necessary now to make a choice, to choose between two admittedly regrettable, but nevertheless distinguishable, postwar environments: one where you got twenty million people killed, and the other where you got a hundred and fifty million people killed.”

President Merkin tries to wake up Turgidson to the fact that he is “talking about mass murder,” not war, but Turgidson is unmoved. He even tells Merkin if he is concerned about being remembered as the “greatest mass murderer since Adolf Hitler” that he should be “more concerned with the American people” than his image “in the history books.”

What Turgidson says fits in with the gallows humor of “Dr. Strangelove,” but it is not much of an embellishment of reality. In Ellsberg’s view, Turgidson fairly represented “the view to be expected in such a situation from any number of Air Force officers, high or low.”

‘The Whole Point of the Doomsday Machine Is Lost if You Keep It a Secret’

During another scene, Russian ambassador Alexi de Sadesky (Peter Bull) informs the War Room that the Soviet Union has a Doomsday Machine that will trigger automatically if the attack ordered by Ripper succeeds. The doomsday device will most certainly annihilate all human and animal life on earth.

What Kubrick probably did not realize was that both the Soviet Union and the U.S. had doomsday devices when he made “Dr. Strangelove.”

Ellsberg’s book describes the Soviet Union’s Perimeter system, which was known informally by a Russian phrase that translated to “Dead Hand.” If the U.S. military had attacked Moscow, it would have resulted in a nuclear winter.

In the film, Dr. Strangelove (Sellers) appreciates the glorious power of a doomsday device.

“Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy — the fear to attack,” Strangelove explains. “And so, because of the automated and irrevocable decision-making process, which rules out human meddling, the Doomsday Machine is terrifying and simple to understand — and completely credible and convincing.”

(Note: Dr. Strangelove was inspired by Herman Kahn, Edward Teller, and Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun.)

Yet there is one major problem. The U.S. government has no idea that the Soviet Union has built a Doomsday Machine. That leads Strangelove to exclaim, “But the whole point of the doomsday machine is lost if you keep it a secret! Why didn’t you tell the world, eh?”

“It was to be announced at the Party Congress on Monday. As you know, the premier loves surprises,” the Russian ambassador replies.

The attention that Kubrick gives to this aspect of nuclear policy gives the movie another layer of sophistication. In fact, as Ellsberg details, the Soviet Union never had any intention of informing the world that the Perimeter system was established. (As of 2017, the Russian government still maintained this real-life doomsday device.)

Valery Yarynich, who designed Perimeter, came to regret his involvement in developing the system and especially opposed maintaining the system after the Cold War ended. He featured in the book, “Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy” by David Hoffman.

“The bottom line,” as Yarynich understood, is that humans are not “a species to be trusted with nuclear weapons.”

While it was not exactly a machine, Ellsberg contended that the U.S. had a doomsday system in place in 1961. Bombers in the Strategic Air Command were on alert and later joined by Polaris submarine-launched missiles. “Although this machine wasn’t likely to kill outright or starve to death literally every last human, its effects, once triggered, would come close enough to that to deserve the name Doomsday.”

The accuracy of “Dr. Strangelove” was owed to Peter George, who received a screenwriting credit (along with Kubrick and Terry Southern). George was a former Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command officer, who wrote the book “Red Alert.” Kubrick bought the rights to “Red Alert” for “Strangelove.”

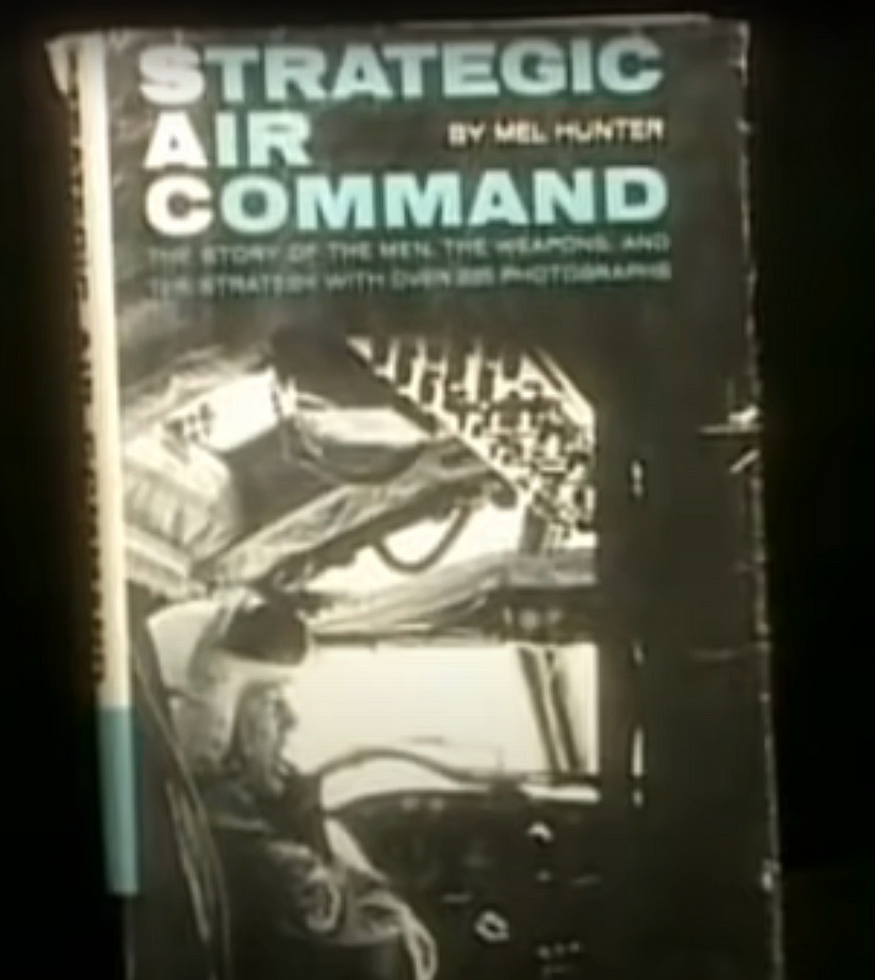

Also, the film was infused with realism thanks to art director Peter Murton, who designed the iconic War Room set. With no U.S. military assistance, Murton referred to a cockpit image on the cover of a book by Mel Hunter called “Strategic Air Command.” That made it possible for the crew to craft a replica of the interior of a B-52 bomber.

Murton spent hours on switches and warning lights, according to the documentary “Inside the Making of Dr. Strangelove.” When publicity people invited U.S. Air Force personnel to look at the set, they were shocked. Even the code receiver box was included in the control dashboard.

Kubrick contacted production designer Ken Adam after the visit to make certain that he had modeled the B-52 bomber set off publicly available materials. The director did not want the FBI to target the film with some kind of an espionage investigation.

Ellsberg, a “movie fanatic,” according to his granddaughter Catherine, considered “Dr. Strangelove” to be a rather funny film. However, he was more than a bit disappointed that it never catalyzed the kind of change in policy that could pull the world back from the brink of catastrophe.

“A lot of people, even a whole book has been written on the theme that, well, this shows you can’t really have a nuclear war because you have to have all these coincidences of sending off missiles and planes with no stop order,” Ellsberg said. “Or having a Doomsday Machine that you didn’t really tell the enemy anything about—that’s really impossible.” Which was false.

“I don’t think many people really thought it could be as realistic as it actually was. So it is worth seeing that movie, but I don’t think it’s ever really evoked the kind of determination to change the system. It’s thought of as, well, that’s an imaginary kind of thing.”

It is easy to look back and regard “Dr. Strangelove” as an artistic byproduct of the Cold War era. Yet as Ellsberg understood, there is tremendous secrecy around nuclear weapons.

Americans do not really know who in the government or the military chain of command has the authority to initiate a nuclear attack. And particularly with the war in Ukraine between U.S.-NATO and Russia, the risk of nuclear catastrophe is as high as it was when Kubrick conceived of one of the greatest comedies of all time.

___________________________________________

Kevin Gosztola is Editor for The Wide Shot, Journalist, film/video college graduate, and movie fan. Member of Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ).

Kevin Gosztola is Editor for The Wide Shot, Journalist, film/video college graduate, and movie fan. Member of Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ).

Tags: Atomic Weapons, Bulletin Atomic Scientists, Manhattan Project, Nuclear Disaster, Nuclear war, Pentagon, Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons TPNW, USA, Weapons of Mass Destruction

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION: