Johan Galtung on Peace Studies, Peace Communication, Peace Journalism: Transcending the Underlying Conflicts

TMS PEACE JOURNALISM, 4 Mar 2024

Joan Pedro-Carañana and Eva Aladro-Vico – TRANSCEND Media Service

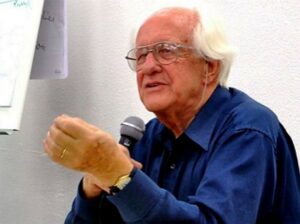

This interview was one of Professor Johan Galtung’s last public appearances. It was conducted by the editors of a special issue of CIC 28 in 2023. Professor Galtung founded peace studies and was an authority in mediation, communication, and peace journalism. The interview was conducted on the occasion of a tribute to him at the International Congress on Communication and Peace, organized by the Latin Union of Political Economy of Information, Communication and Culture (ULEPICC-Spain).

Introduction

For this special issue on Communication and Peace in homage to Johan Galtung, Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación (CIC) had the privilege of interviewing the honoree, who spoke with Joan Pedro-Carañana and Eva Aladro-Vico about his life and work, which were tirelessly dedicated to peace and social justice. The interview took place in the framework of the International Congress “Communication and Peace”, held by the Spanish chapter of the Latin Union of Political Economy of Information, Communication and Culture (Unión Latina de Economía Política de la Información, la Comunicación y la Cultura) (ULEPICC-Spain) at the Complutense University of Madrid in March 2023. A video of the interview is available at the ULEPICC-Spain channel.

When we began to think about this special issue in homage to Galtung, we were excited about the idea of trying to interview him. What better way to present, apply and celebrate his work and figure, but also to discuss and question his contributions -always in a constructive spirit- than to do so in the company of the admired teacher? As the main founder of peace studies, Galtung is internationally recognized as one of the most influential and relevant scholars for understanding and researching societies and their conflicts. In 1959 he founded the International Peace Research Institute, the first research institute on peace and conflict, of which he was the director for a decade. In 1964, he launched the prestigious Journal of Peace Research.

Eva Aladro-Vico has been acquainted with Galtung’s work since the end of the last century, when she was trained in theories of journalism. Johan had already laid the foundations of these theories in the 1960s. Knowledge of the working methods and professional routines of reporters had been of interest for some decades, but Galtung and Ruge’s foundational study from 1965, “The Structure of Foreign News”[i], was crucial. This seminal paper claimed that journalists followed so-called newsworthiness criteria to decide what to publish as news and what not. In many cases, these criteria were not substantive, or linked to the essential importance of the facts, but rather associated with some specific norms: proximity, the availability of material to cover, the number of people involved, the position of the journalist in the newsroom, and other social class criteria.

Galtung explained[ii] that this research led him to recognize a general tendency: making violence and negativity a matter of primary importance for large numbers of people. Positive issues are reserved for the elites; the tendency to relate people of lower class or “underdogs” with negative events is clear. And to select massively negative events against positive events for minority elites or “topdogs”, makes both symbolic or cultural violence and structural violence prevalent in the media, for reasons that are not objective, but related to the way the media develop their information agendas. At the same time, in the 1960s Johan was developing his research on types of violence in the development of peace studies[iii] with the founding in 1964 of the Journal of Peace Research[iv]. It is only logical that, within his integral theory against violence, he developed the perspective of peace journalism in his early work with Jake Lynch,[v] and analyzed the social position of the victims of violence.

What is the lesson of these contributions? Journalists must incorporate an alternative approach to the war journalism that has been dominant in our societies for a century. The difference between conflict and violence is crucial. Conflict must be normalized and detached from violence, seeking a non-polarized overview vision of situations. Independence from propaganda and the systemic exclusionary approach of elites and sources of power is also essential. As a great admirer of Daoism and Gandhian philosophy, Galtung has been able to see beyond the type of journalism that perpetuates violence and social inequality. Empathy, commitment to peace, contextual analysis, and the ability to increase options towards harmony are part of the crucial values of peace journalism. For many of us, Galtung is therefore a crucial reference in professional, ethical, political and philosophical inquiries of journalism, a privileged author in disciplines related to our entire field, something which not all social and human behavior analysis can boast.

This interdisciplinary approach first impressed Joan Pedro-Carañana when he had the privilege of attending as an undergraduate student a PhD seminar given by Galtung at the University of Alicante in 2003. For years, there had been developing a solid international school of thought, with readings, conferences, and dialogues that showed how peace studies and peace journalism and peace communication offered key tools of analysis of social reality. These tools help to think and make the social changes that must be carried out in complex societies, today more urgently than yesterday, to build more peaceful cultures -also with respect to the environment-, ensuring their own survival. In Spain, the Instituto Interuniversitario de Desarrollo Social y Paz (IUDESP) stands out in its dedication to this pairing of social development and peace from a multidisciplinary perspective. Its critique of functionalist conceptualizations comes with promoting interdisciplinary dialogue. The work of this institute, based at the Universitat d’Alacant, has undertaken peace studies and peace research from the perspectives of sociology and the sociology of communication, while the group at the Universitat Jaume I de Castelló is key in understanding and promoting peace communication and peace journalism.

Academia in the Nordic countries has made great contributions to peace studies, but it should be noted that Galtung’s teachings have been applied and expanded in many other contexts. For example, in India, the tradition of nonviolent action and communication based on Gandhi’s legacy has an important presence. Galtung’s work is also known and applied in Latin America, where theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and analyses based on specific contexts have been developed. There are compatible approaches to Galtung’s that necessarily differ, due to characteristics of the place of enunciation. It is worth highlighting the central role given in these countries to the construction of narratives of resistance, resilience, dialogue, social change, and eco-social justice. There is no doubt that thinking about peace from different loci helps to reduce and correct the ethnocentric imprints that every culture bears to a greater or lesser degree. An internationalist approach enables contributions that can be of interest to learn -not copy- in other contexts, including Europe and the USA. For example, learning about communication from the perspective of the good life (Sumak Kawsay, Suma Qamaña, Buen Vivir), decoloniality, the pluriverse or communicative justice.

Many of us have learned theoretical and methodological approaches from Galtung, as well as dialogical practices that are key to understanding the foundations of conflicts and how to transcend them by promoting agreements favorable to all parties, to social justice and human dignity. Galtung developed the well-known Triangle of Violence model based on a holistic and dialectical perspective, teaching us to look not only at direct violence, but also at structural and cultural-communicative violence, as well as ways of transforming them to resolve underlying conflicts. In the face of powerful structures of violence, Galtung conveys the value of human agency in transforming structures and, thus, the capacity of human beings to create and change the world. Therefore, his legacy includes a way of thinking and practicing that promotes action, communication, and education capable of transforming conflicts nonviolently, empathetically, and creatively.

Based on this background as a starting point, we wanted to ask Galtung about current conflicts, the relevance of peace studies, and the role of peace journalism and communication in today’s changing media, technological, and communicative environment. We were fortunate to have the collaboration of several people close to Galtung, who facilitated the meeting we had by video call. Galtung taught he retired Professor of Sociology José María Tortosa or, as the latter likes to say, was one of his teachers, remembering what the former said to him, namely that it is always necessary to diversify intellectual references. Professor Tortosa, one of Pedro-Carañana’s teachers, put us in touch with Irene Galtung, Johan’s daughter, a brilliant and kind lawyer specializing in the right to food and drinking water. She put us in contact with Johan and his wife Fumiko Nishimura to arrange a virtual meeting with the collaboration of her assistant Masiel Cardozo, who, we were told, makes very delicious arepas.

At 92 years of age, Johan Galtung welcomed us on 11 January 2023 with a sincerely happy smile and the kindness of the peacemaker at peace, as a great conversationalist who welcomes you into his living room, even virtually. Although the light was dimmed to take care of Galtung’s delicate eyesight, we could see his cheerful face, but he could only partially see us because of some technological difficulties. Annoyed that he could not recognize our faces, he invited us to distance ourselves from the camera. We did so, and Galtung revealed a face of serene emotion typical of what the theory and practice of nonviolence calls soul-to-soul communication. This is how affective bridges are built between people that, naturally, are accompanied by rational bridges that allow us to walk the path of “feeling-thinking” (sentipensares), in the words of Orlando Flas Borda. These paths led, for example, to the founding of TRANSCEND International in 1993, a network for peace, human development, and environmental care. TRANSCEND is a key example of the influence of Galtung’s work beyond the strictly academic, in the formation of networks of thought, solidarity, communication, and action that seek to influence society. The network includes Transcend Media Service,[vi] a landmark in solutions-oriented peace journalism.

Galtung has developed his own way of seeing the world from the perspective of complexity. He always bears in mind relational and conversational aspects A man of dialogue or, as he explains here the term he prefers, of conversation; a person who has never missed an opportunity to share, listen, and learn from others. A great human being who brings back faith in the species.

A great human being, we think, that restores hope in humanity and, therefore, hope to societies, collectives, and individuals from different parts of the world who wish to transform it. This is attested to by the large number of international awards and recognitions he has received, among them the Alternative Nobel Prize (1987), the Gandhi Prize (1993) and, more recently, the Leif Eiriksson Peace Award (2022) (see video tribute in Transcend Media Service).

We were thinking of doing the interview in English in case it was more comfortable for him, but after speaking for a while in Spanglish, we asked him and, as a good mediator-communicator who knows how to adapt to his interlocutor, he told us to do it in Spanish. A polyglot, he did it without difficulty and was aware of the importance of languages. He is a globalizer of peace culture, which requires a lot of interculturalism -and he must know something about this after mediating in more than 150 conflicts between and within different countries.

Galtung spoke to us in a fragile voice, but with the flexible and gentle firmness of the wise and with relentless logical thinking about his lessons and teachings in relation to both major world events and everyday life and interpersonal relationships, including his own marriage. He was happy for us to follow him on Twitter, and we took the opportunity to read to his thoughts on the internet and social media. Galtung, unsurprisingly, keeps hope alive, but by no means falls into mere idealistic voluntarism. He makes clear the difficulties facing peace. It is precisely the diagnosis that identifies the material, cultural and military difficulties that makes it possible to see that there are real possibilities for change–without forgetting that Galtung has always been scathingly critical of those who refuse to engage in dialogue and insist on seeking war by any means necessary. He also reminds us of the importance of thinking that one can be wrong and contributes to or is the cause of a problem. His ability to synthesize complex thinking and, therefore, to make the difficult become easy, is evident in the transcript below.

Interview

CIC: We would like to start by asking you why you started to develop peace studies. Was there any experience or event that prompted you to work in this line and crystallized into this concept?

JG: There was an experience in the world, World War II, with Norway occupied by the Germans; this was only one aspect, a completely unnecessary war. You could have changed the situation. And then the concept arose that we have to look for the underlying conflict and resolve the conflict. Then we can fix it.

We have a very positive experience in the Scandinavian countries, and the Scandinavians know very little about this, but we have had wars and wars and wars. Now, such conflicts are unthinkable -ah, that depends a little bit on the imagination of the thinker- but they are very unlikely. Something has happened, they have discovered that cooperation is much better than violence.

The opposite word to cooperation is not conflict. Conflict is just disagreement. And disagreement can be resolved. It is very important to resolve it. A keyword is to transcend. To find something satisfactory for both parties. And not a compromise, which is deviant, and a little bit stupid, half-half, and which does not change the situation.

CIC: Speaking of transcending, is it a concept that you integrated from Eastern philosophy and thought, or is it a concept that came to you from your thinking and studies in the West?

JG: That’s a question, hehe, a little too long. My wife is Japanese, that has helped me a lot. I’m very grateful to her because there’s always a different perspective. I learned that perspective from her as an individual, but also her perspective as an Eastern person, or an Eastern perspective, because the East is not only Japan. You can imagine, living in an Eastern-Western, Japanese-Norwegian marriage: Every day, a new occasion to learn. I have benefited so much from that, I am so, so grateful to my dear wife.

CIC: Wonderful. And looking back to the time when you started developing peace studies, do you see parallels with the world today, and that your framework of conflict resolution is useful today?

JG: Naturally, I believe that. There is a formula that everybody knows, which is a very bad formula: it is the compromise: we agree, half to me and half to you. That reproduces exactly the same conflict, maybe at a lower level, just like at the beginning. So, the question is not to reach a compromise, what we have to do is what we call transcending. Transcend the situation in another way.

An example is the Scandinavian countries, where we have the experience of violence, violence, violence, oppression, oppression, and oppression, but we also have the opposite experience, and then, more or less, we have decided that we don’t want any more of that, and it turned out well. It has worked out very well. Now, a very bloody and very violent conflict between Scandinavian countries is, as many say, unthinkable. That depends a little bit, as we say, on the imagination of the thinker. But I am convinced that it is very, very unlikely.

CIC: Concepts such as peacekeeping, peacemaking, and peacebuilding have been very important in your work to transcend conflicts.

JG: If you do something, and you have a positive response, and you have a positive development, that helps a lot. You really get the idea, and with it you can follow a good path. But being empirical, you have to respect the facts and not be dogmatic: That’s why what I have said, this definition of transcending, is the solution.

Some idiots don’t understand because they are stupid. It may be that they are a little bit stupid, but it may also happen that the stupidest person is yourself. This is a starting point. And respecting what they say, you have to enter into dialogue. Dialogue, dialogue, dialogue: How it would have been if instead of doing this, I had done that. Listening, hearing, understanding, dialoguing. We can understand each other with words, which are a divine gift, and therefore we can have very deep contact with others, including the person with whom we have problems.

CIC: Are you optimistic about people’s ability to change, or do you think change is very difficult?

JG: Look, it is very difficult. But the difficulty may not necessarily lie with others. One important factor is that we all tend to blame others. To understand that only others have responsibility for the situation, and that only others have influenced the situation.

CIC: Back in 1987 you criticized the idea that nuclear arms would prevent nuclear war. You said it was a myth. Do you think that is still the case today?

JG: We have the nuclear threat, and we also have biological and chemical threats, which are not necessarily better threats one or the other. I think what matters less is the nature of the weapons. What matters most is the underlying factor, always in my judgment, which is what requires our effort. And the solution in general is almost never a compromise, but what I call transcendence, which is to create a new reality, to transcend into a new reality.

We need to discuss concretely what that means, that is the dialogue between people.

CIC: You also criticized the just war doctrine. Do you still believe that there is no such thing as a just war?

JG: A war is always unjust. If it uses violence, it cannot be just. A just war is a vocabulary that is also a cause of war today, because one side always announces a war as totally justified, and the other side does exactly the same thing: No, no, no, no, no, in my way of seeing the thing, it is a just war. So, in war we always have two just wars, which is something more than two wars, we have two justifications. It is a part of the culture of both sides, and that culture comes in as a causal factor.

We have to grow up, mature and always say that just war does not exist. It is a contradiction in words. It is just peace that we must look for, because with it comes the understanding of the parties. Because with peace you understand this, and I understand it a little bit different. In it we can see what you have against my concept, and I will tell you what I have against your concept. We can have a useful instrument for all this, dialogue. To enter a dialogue is to be able to understand each other a little bit, without pretension, for which we have to prepare ourselves a little bit. Preparation means to think, to understand, to use this cell up here [referring to the head], to think a little bit, what it is all about. It is very important to know that I have understood. It is a very, very important thought, because in this idea, we have done something: With it comes curiosity: what is it that he has seen that I have not seen. Tell me. Then, we have a dialogue. One sees things one way or the other. We analyze the two points of discussion and not others. Then, together, we will discover other points of disagreement. And of agreement. Because the world is rich, there are so many ideas, and every problem has so many sides, angles, ways of solution -always-, and the more you refine your knowledge, the better.

CIC: Professor, how have you managed to maintain that vitality of mind that you have, to keep advancing in knowledge and thought? Do you have a formula, to tell us and our students?

JG: Keep the peace?

CIC: Internal peace

JG: Yes, peace you can keep. For example, I am Scandinavian, I am Norwegian. I know well unfortunately the last 9 centuries of history, almost 1000 years in that part of the world. We have had lots and lots of wars, lots and lots of conquests, and we have come out of that, we have enjoyed the experience that that coming out is better. Cooperation is better than violence.

Here, very importantly, the opposite word to cooperation is not conflict. Conflict is something that we can solve, for example, with compromises. It is a formula, perhaps, of the least intelligent. It is not a very advanced formula. You can know reality better; here comes the research for peace, of peace, from peace, to peace, and with it you can elucidate and distinguish. And that has been my principle. I am on that path. In a way, I have the idea that I discovered the path; I have only the idea that I am on the way. I am at the beginning of the path.

CIC: How beautiful.

JG: And if we keep talking, we will solve more problems. We are going to discover everything that social existence produces.

CIC: We also wanted to ask you, Johan, about peace journalism. How can journalists and communicators help resolve conflicts?

JG: By doing exactly what you are doing. You are with me, for example, in a dialogue, not only in the sense of you asking the questions and me giving my answers, but also in the sense of being in a conversation. The word I like best is not dialogue, but conversation. Conversation is more symmetrical in that dialogue depends on who can convince the other. In a conversation the same thing can happen, but it can also present very interesting aspects for both, which demand to be continued with those aspects.

I think this conversation that the three of us are having right now has this characteristic: it is so interesting that we can continue it. Not in the sense that I want to win, to dominate; aha, Johan, very good Johan… but in the sense above all that I want to teach something new, that can be better. This is called transcending. Transcend, to go beyond.

CIC: Johan, do you think the new social networks can be used for conversation, or do you think they can’t be used for people to learn through conversation?

JG: I like it so much that you use the word conversation! Much better than dialogue. Because in the word dialogue there is more or less the idea that one is going to win and the other is going to lose. In conversation, however, the other is going to say: Thank you, thank you, now I understand, I understand, thank you, thank you, thank you. That is the conversation. You talk, and the other party learns. You dictate things, and the other party dictates things. That’s good conversation.

I have an example that everyone knows. You throw a party. You invite guests, friends, partners, they are there, they fill the room, and a conversation starts. But there is one rule: No one completely dominates the conversation. There is a rule, symmetry. Not perfect symmetry, that doesn’t exist. But as symmetrical as possible. So, in the party there may be a person who says: Now we have understood how he, and them and she, etc., thinks about the situation. But we haven’t heard a word from you, what you think. So, we want to hear what you think. So, at a good party, with everybody sitting around, with good things to eat and especially to drink….

CIC: Hahaha

JG: …They all talk, and then they talk too much, but they talk.

CIC: That happens, hahahaha.

JG: One can gently lead a little bit, saying that I think I understand his opinion very well, and hers, and his, and his, etc., but you are missing, you have not spoken, so far, and this person who has not spoken, says: I have not spoken because you all have misunderstood the world we live in. That is different, an interesting sentence. So, the question is, explain, what is it that we have not understood. And then you can be convinced, either he or she has exaggerated a little bit the importance of his or her position, she has spoken well, but… so, let’s understand. I prefer the word conversation to the word dialogue. In the word dialogue there is always an idea of struggle or fight. In the word conversation, we always have an image of people who are well seated, well entertained, with food, drinks, and partying, relaxed, and conversing well, all of them, trying to find compatible points, and to undo the incompatible ones.

CIC: You will remember, professor, that the Greeks called banquets and feasts agape, but the word agape also means love. So, for the Greeks, being together, conversing, celebrating, was also the highest form of love, the Greek “agape”, wasn’t it?

JG: That’s all very important. I agree. Very important, because we always have in that a model, they’re sitting down, they’ve had a good meal, they’ve had a good drink, and they’re in a conversation. And that conversation is a model of how to resolve conflict, because they feel good, they know that everything is allowed, except for silence. If you don’t want to participate you can say, look, I’m not interested in that, I’m not cut out for that. So, I’ll come tomorrow, and I’ll see if you have developed something that interests me more. That’s completely permissible. I already know what he or she thinks, and I don’t intend to force you to participate in the conversation. I prefer the word conversation to the word dialogue.

CIC: And social networks? Do they provide the conditions for conversation? On the Internet: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram?

JG: On the Internet, you are the one who allows the conversation or not. You say yourself: I don’t agree with that word, I don’t like it. I’m not going to participate, or I’m not going to allow this person to participate. We have found an innovation: an Internet that seems neutral, which can allow everyone to participate. There is no entry card on which everything depends, and according to which it is said that I am a supporter of such and such a thing. Since there is no entry card, you are welcome.

CIC: Professor, we don’t want to take up too much of your time because you will have to eat now.

JG: Now? great idea!

CIC: Hahahahahah…but we should be able to eat together, hahahahaha!

JG: We have mentioned eating, so it’s time to wish you a good meal.

CIC: Likewise, likewise, thank you very much, professor. It has been a great pleasure. (Applause from CIC and Galtung). Bon appétit, and may you continue to give us so much energy.

NOTES:

[i] Galtung, J. and Ruge, M. (1965). The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2, pp. 64–91.

[ii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=64EfDD2Svsg&ab_channel=TranscendMedia

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johan_Galtung

[iv] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=64EfDD2Svsg&ab_channel=TranscendMediajake

[v]https://books.google.es/books/about/Peace_Journalism.html?id=iiobAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=yme

[vi] https://www.transcend.org/tms/

__________________________________________

Published in Spanish in Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación

Joan Pedro-Carañana is in the Department of Journalism and New Media of the Complutense University of Madrid. He has a European doctorate in Communication, Social Change and Development. His interest lies in the role of communication, education and culture both in the production of hegemony and in emancipatory social change. He is co-editor of Communicative Justice in the Pluriverse. An International Dialogue, El Modelo de Propaganda y el Control de los Medios, The Propaganda Model Today: Filtering Perception and Awareness (Open Access), and Talking Back to Globalization: Texts and Practices. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Latin Union of Political Economy of Communication, Information and Culture. He collaborates with Open Democracy, Propaganda in Focus, CTXT, Rebelión and Amanece Metrópolis. Part of his work can be found HERE.

Joan Pedro-Carañana is in the Department of Journalism and New Media of the Complutense University of Madrid. He has a European doctorate in Communication, Social Change and Development. His interest lies in the role of communication, education and culture both in the production of hegemony and in emancipatory social change. He is co-editor of Communicative Justice in the Pluriverse. An International Dialogue, El Modelo de Propaganda y el Control de los Medios, The Propaganda Model Today: Filtering Perception and Awareness (Open Access), and Talking Back to Globalization: Texts and Practices. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Latin Union of Political Economy of Communication, Information and Culture. He collaborates with Open Democracy, Propaganda in Focus, CTXT, Rebelión and Amanece Metrópolis. Part of his work can be found HERE.

Prof. Eva Aladro-Vico, Ph.D. works in the Department of Journalism and New Media, at the Faculty of Information Sciences in Complutense University, Madrid (Spain). She is specialised in Information and Communication Theories. Coordinator of the Academic Journal CIC Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación and director of the research group “Communicative Structures and Interactions between the Different Levels of Interpersonal Communication”. She has written a variety of books in Spanish such as Teoría de la Información y Comunicación Efectiva, Las Diez Leyes de la Teoría de la Información, Comunicación y Retroalimentación, Símbolos, Metáforas y Poder, o La Información Determinante. She is a writer of a blog and of poetry, with eight books of poems edited. She publishes articles about Ecology and Information Theory in the Spanish digital newspaper eldiario.es and in The Conversation. Part of her work is available here: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=MdVEEs4AAAAJ&hl=en

Prof. Eva Aladro-Vico, Ph.D. works in the Department of Journalism and New Media, at the Faculty of Information Sciences in Complutense University, Madrid (Spain). She is specialised in Information and Communication Theories. Coordinator of the Academic Journal CIC Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación and director of the research group “Communicative Structures and Interactions between the Different Levels of Interpersonal Communication”. She has written a variety of books in Spanish such as Teoría de la Información y Comunicación Efectiva, Las Diez Leyes de la Teoría de la Información, Comunicación y Retroalimentación, Símbolos, Metáforas y Poder, o La Información Determinante. She is a writer of a blog and of poetry, with eight books of poems edited. She publishes articles about Ecology and Information Theory in the Spanish digital newspaper eldiario.es and in The Conversation. Part of her work is available here: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=MdVEEs4AAAAJ&hl=en

Tags: Conflict Mediation, Johan Galtung, Nonviolent Journalism, Nonviolent communication, Peace Journalism, Peace Studies

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 4 Mar 2024.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Johan Galtung on Peace Studies, Peace Communication, Peace Journalism: Transcending the Underlying Conflicts, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

TMS PEACE JOURNALISM: