- The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon by Adam Shatz Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 451 pp.

- Fanon’s Dialectic of Experience by Ato Sekyi-Otu, Harvard University Press, 276 pp.

Fanon the Universalist

BIOGRAPHIES, 20 May 2024

Susan Neiman | The New York Review – TRANSCEND Media Service

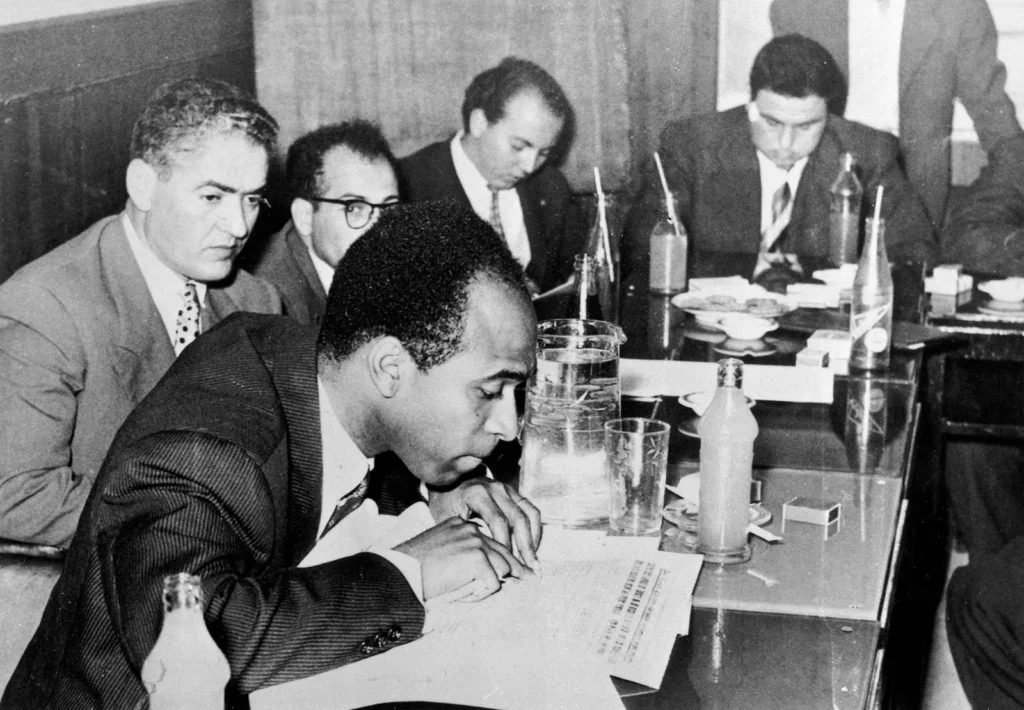

Frantz Fanon, front, at a press conference during the Congress of Writers, Tunis, Tunisia, 1959. Archives Frantz Fanon/IMEC

6 Jun 2024 Issue – Frantz Fanon, the supposed patron saint of political violence, was instead a visionary of a radical universalism that rejected racial essentialism and colonialism.

Yet what if we could return to Fanon’s vision? For what he proposed was not only a robust and radical universalism but also an end to colonialism—to the assumption that it’s natural to base international relations on inequalities of power, which has plagued us since recorded history began. The proposal was idealistic enough in Fanon’s day; it will seem utopian in ours. But honestly, look around you: What do we have to lose?”

Decolonization, said Frantz Fanon, began a new chapter of history. It’s common enough for the politically engaged to magnify their engagement, if only to sustain themselves through the cycles of danger and boredom that accompany serious political struggle, but in this case Fanon might have understated things. Stronger nations have overtaken weaker ones since the beginning of recorded history—indeed, since before there were nations in our sense at all. Contrary to much current opinion, colonialism did not begin with the Enlightenment, whose ideas were later twisted to support it.

Until the last century imperialism was as universal a political practice as any: the Romans and the Chinese created empires, as did the Assyrians, the Aztecs, the Malians, the Khmer, the Mughals, and the Ottomans, to name just a few. Those empires operated with different degrees of brutality and repression, but all presupposed the logic recorded in Thucydides’ dialogue between the Athenians and the Melians: big states swallow little ones as night follows day. It’s a law of nature against which reason has no claim.

Enlightenment philosophers asked whether such assumptions really are as natural as alleged, and they used their reason to ground a thoroughgoing attack on colonialism. Kant congratulated the Chinese and the Japanese for their wisdom in refusing entry to “unjust invaders”; Diderot urged the “Hottentots” to let their arrows fly toward the Dutch East India Company. Like progressive intellectuals in our day, these thinkers had limited political success, at least in the short term: the colonial projects they condemned only expanded in the nineteenth century. Pace the ambivalent American experiment, it wasn’t until the twentieth century that Enlightenment ideals about universal human rights began to undergird real anticolonial struggles from Ireland to India.

No one represents those struggles more clearly than Fanon, whose life and work have inspired books that often reveal more about their authors than their subject. “Fanon,” wrote Henry Louis Gates Jr., “is a Rorschach blot with legs.” In recent years Fanon has been seen as the patron saint of postcolonial theory whose rejection of all things white and Western rivals that of the grimmest Afropessimist. Adam Shatz’s The Rebel’s Clinic presents him instead as someone who lived against the tribalist essentialisms we’ve come to expect from contemporary progressive thought. It is not only a superb addition to a large and largely hagiographic literature; it is also a contribution to one of the greater theoretical challenges we face today: Is it possible to create a genuinely universalist political ethic that avoids the pitfalls of earlier ones?

The Rebel’s Clinic portrays Fanon and his time with nuance and complexity, and it underscores his ongoing relevance. Not the least of the book’s virtues is its portrait of an unfinished Fanon. Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, to whom he dictated his last works, was both amused and exasperated that his writings were dissected in universities. “These were pamphlets!” she protested. So, of course, was The Communist Manifesto. Shatz believes that Fanon’s texts should be debated in universities, but not as theory straining for timelessness. Fanon was brilliant, he was brave, and he was very young when he died. When would he have had time to construct a flawless doctrine?

Fanon’s biography leaves the reader wondering how he managed to pack so much life into thirty-six years. As Shatz takes pains to emphasize, no simple story can do justice to his identity. He was born in 1925 to a middle-class family with socialist leanings in the French colony of Martinique, considered as much a part of France as Brittany or the Loire. His paternal great-great-grandfather was enslaved, but his father’s family had long been free people with property, and they provided the children with piano lessons and a weekend cottage in the country. His mother’s family was originally from Alsace, and though her ancestry wasn’t white enough to allow her to socialize with the island’s békés—descendants of planters—the Fanons identified with the France that had proclaimed the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

Martinique’s leading writer and activist, Aimé Césaire, made the island a center of Négritude, the international movement that sought to liberate Black humanity from domination by white cultures by elevating Black difference. Still, “Je suis français” was the first sentence Fanon learned to write. In 1944, at eighteen, he ignored his family’s and teachers’ admonitions “not to get mixed up in a white man’s war,” Shatz writes, and enlisted in Charles de Gaulle’s Free French Forces. Though influenced by Césaire, Fanon began life in loyalty to the France that understood itself as the birthplace of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

West Indians training with French forces in North Africa were considered honorary Europeans and granted privileges African soldiers did not share, but the absurdity of fighting fascism in a force structured by complex racial hierarchies undermined Fanon’s faith in France. That faith was further undone in the war’s aftermath. Under American pressure, Black soldiers were excluded from the triumphant Allies’ march into liberated Paris in August 1944, though most of de Gaulle’s army came from the colonies. During the celebrations of the liberation, the Martinique veteran, who loved to dance, found no Frenchwoman willing to dance with him. As he was recovering from battle injuries, Fanon wrote to his family that he had been wrong in deciding to fight for France. He concluded by saying he doubted everything, even himself.

Yet it took him some time to give up on France entirely, and perhaps he never did.

Taking advantage of the free education to which veterans were entitled, he chose to study medicine in Lyon because, he said, “there are too many nègres in Paris.” Shatz quotes this remark as a joke Fanon made to his brother but also asks why he avoided Paris, with its vibrant West Indian community, in favor of notoriously provincial Lyon. He argues that although Fanon might have longed to become part of a community—later calling himself Algerian, though few Algerians would have agreed—“he wanted to invent himself, and to be known first and foremost as a self-made man.” If so, that explains his immediate attraction to existentialism, the philosophical movement that swept France, and Europe, in the heady years after the liberation.

“Existence precedes essence,” the phrase with which Jean-Paul Sartre defined existentialism, could begin a neo-Heideggerian riff on the nature of Being, but it’s a claim with political consequences. Though Sartre’s and Simone de Beauvoir’s contributions to the war effort were hardly as serious as they or their admirers liked to suggest, Shatz rightly calls existentialism “the philosophical continuation of the ethics of the wartime Resistance” and shows its centrality to the development of Fanon’s thought. If existence precedes essence, we are born free, undetermined by biology or history. It follows that essentialist views like the Senegalese writer Léopold Senghor’s version of Négritude, which claimed that “the African is a ‘man of nature,’ a ‘sensualist,’ living ‘traditionally off the land and with the land, with and by the cosmos,’” cannot stand. Shatz distinguishes Césaire’s version of Négritude, which allowed for certain forms of self-invention, from Senghor’s essentialist view, which suggested that reason is Greek, emotion African. (In Fanon’s Dialectic of Experience, the Ghanaian philosopher Ato Sekyi-Otu calls this a left-wing version of the ideas of the nineteenth-century French racist Arthur de Gobineau and lambastes readings of Fanon that try to press him into its service.)

In the end, however, Fanon turned away from Césaire as well as Senghor and toward Sartre’s version of universalism. “What’s all this about Black people and a Black nationality?” he asked in Black Skin, White Masks (1952). “I am French. I am interested in French culture, French civilization, and the French. We refuse to be treated as outsiders.” Fanon’s work, Shatz argues, is a celebration of freedom.

And yet he was an outsider wherever he went. Though he came to refer to himself as Algerian and arranged to be buried there, he spent less than three years in the country and never learned Arabic or local Berber languages; as a psychiatrist treating patients, he had to rely on translators. Nor did he understand the ways in which Islamic culture dominated the land he adopted. Perhaps that feeling of never quite being at home in the world—as existentialist a trope as any—remained the one in which he felt most at home. Shatz draws on the sociologist Georg Simmel to argue that strangers can hear and understand things that native observers tend to miss.

The event that fixed Fanon’s sense of himself as fundamentally Other took place during his studies in Lyon, where his skin color was conspicuous. When a boy on a train called out, “Look, maman, a nègre!” Fanon’s hopes for being “nothing but a man” took a blow. Nor were they improved when the mother attempted to salvage the scene by saying, “Look how handsome the nègre is.” “The handsome nègre says, fuck you, madame,” replied Fanon, feeling momentarily free, but the incident stayed with him for life. Like the child who innocently revealed the emperor’s nakedness, the boy exposed the hollowness of French claims to see only the universal.

The power and pain of that revelation were amplified as Fanon began to work as a doctor and witnessed his colleagues’ treatment of Algerians in France. The colonial hierarchy cast him as a middle-class Frenchman, but he identified with his patients instead. French doctors treated their ailments as imaginary, a function of “North African syndrome,” at the time an accepted diagnosis meaning hysteria over fictitious pain.

Drawing connections between colonialism and mental illness that would be among his most lasting contributions to psychology, Fanon came to believe that colonialism was a system of pathological relations masquerading as normality. “For a man armed solely with reason,” he wrote, “there is nothing more conducive to neurosis than contact with the irrational.” Though he thought neurosis, and even psychosis, could be understood as reasonable responses to unreasonable relations, Fanon criticized Jacques Lacan and other left-wing psychiatrists whose reappraisals of their profession often idealized mental illness as a protest against a world gone mad. “Madness itself does not command respect, patience, indulgence,” he wrote. Far from endorsing a critique of reason as an instrument of domination, he believed that reason was a weapon the weak could use against the powers that oppressed them. Madness, by contrast, is a barrier to freedom. His decision to become a psychiatrist was a way both to study and to heal people in all their particularity.

Fanon was a psychiatrist before he became a revolutionary, and Shatz argues that his thought was shaped by experiences of confinement—in asylums and clinics as well as “the prison house of race.” Hence the biography’s title, and several chapters devoted to the evolution of his psychiatric practice. Repelled by the rigid and racist methods he witnessed as a young doctor, Fanon found a home at the Saint-Alban asylum in southern France. There he learned new approaches to psychiatry that blended Freud and Marx and gave the mentally ill an autonomy that was absent in traditional psychiatry. Saint-Alban had been a center of resistance during the occupation and was run by François Tosquelles, a refugee from Franco’s Spain who created the psychiatric services of POUM, the anti-Stalinist Marxist party during the civil war. A revolutionary who viewed psychiatry as a continuation of politics, Tosquelles became Fanon’s most important mentor.

After interning at Saint-Alban, Fanon was ready to direct an institute, but his choice to head the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria was not a political act. Few at the time could imagine an imminent national struggle in North Africa. The young doctor was a representative of colonial authority who took a good civil service job in France’s prized colonial possession. Yet he brought with him a striking openness to learning from his patients that would eventually ground his commitment to the Algerian Revolution.

Fifteen hundred patients, mostly Muslim men, were housed in the Blida hospital. Only half had beds; some were tied to trees or chained naked to iron rings on straw-strewn floors. Fanon intended to reform the clinic using the methods he had learned at Saint-Alban. His students were struck by his ability to listen to patients, enabling them to talk without fear. Even complaints about the quality of hospital food, Fanon told his staff, helped develop a sense of nuance. Still, he was considered European by his Muslim patients, and Tosquelles’s methods did not work in Algeria: there was no interest in the theater and film clubs that had structured patients’ days in southern France. Rather than giving up on reform, as his European colleagues urged, Fanon worked with a team of Muslim nurses to create the cultural settings that patients knew from their lives outside the clinic. However banal it may sound today, the idea that psychiatry in a colonial society should draw on the life experiences of the colonized was revolutionary. While continuing to view Négritude as a form of mysticism or worse, Fanon came to understand culture as a bulwark of psychological resistance.

The war for independence began shortly after Fanon arrived in Algeria, and the Martinique native who’d been wounded for—and by—France sided with the colonized. His clinic became the only place where fighters could have their wounds, whether physical or psychological, treated without fear of arrest. Fanon served the revolutionary soldiers there as his mentor Tosquelles had served Republican fighters in Catalonia. It was his good fortune, Shatz argues, to fall in with the most open-minded group in the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN): Marxists who believed that national revolution was only worthwhile as a prelude to social revolution. It’s a view that Fanon would refine in his later work, as the clinic itself became a laboratory of revolution, and revolution the ultimate expression of his work as a doctor. When Fanon finally met Beauvoir in Rome in 1961, he told her, “All political leaders should be psychiatrists as well.”

It was not to be. Brutal violence in Algeria had exploded long before their meeting, and both Sartre and Fanon were targeted by assassins. The revolution was not following a course either thinker could welcome, though neither saw it clearly at the time. To appeal to rural Algerians, the FLN began to emphasize populist Islam, portraying what began as a secular anticolonial struggle as a Muslim holy war. While fearing the bloodbath he predicted, Fanon came to accept it. He was shaken by a close friend’s murder in an internecine FLN struggle, but he never spoke out against it—at least partly, Shatz suggests, because his own position within the FLN was insecure. When the colonial government discovered the hospital’s support of the rebels, it expelled Fanon. Like many of his colleagues, he fled to neighboring Tunisia, whose government provided a base of operations for the revolutionaries. In Tunis Fanon opened Africa’s first psychiatric day clinic, which he intended to be a model for other underdeveloped countries. At the same time he treated the physical and psychic wounds of Algerian soldiers at the border so they could return to battle.

Fanon’s view that the Algerian Revolution was not just an anticolonial struggle but a social revolution was a projection, even a myth. Though he called for liberation from inherited traditions as well as colonial oppression, he never saw the gap between his own ideals and the revolution that was actually unfolding. The FLN needed diplomatic support wherever it might come from, but it hardly supported Fanon’s hope that revolution in Algeria would lead to a Pan-African socialist uprising. Nor were other African countries keen on imitating the sort of battle that was devastating Algeria. The FLN’s appointment of Fanon as its roving ambassador to Black Africa in 1960 was a means of courting African goodwill but also of getting an intense, charismatic leftist out of the way.

The last chapters of Shatz’s biography reflect the sadness of Fanon’s final years, when he was trapped between rising nationalism, Islamism, and cold war politics. His belief that the Maghreb could be united with the rest of Africa by the common struggle against colonialism was shared by few north or south of the Sahara. Colonialism, he came to argue, was not the greatest threat to African independence; the graver problem was the lack of a genuine political project that went beyond exchanging corrupt European rule for corrupt local rule. The leukemia that would soon kill him sapped his strength but not his ambition as he strained to dictate The Wretched of the Earth (1961), which came to be called the Bible of the anticolonial movement by figures as different as Stuart Hall and Eldridge Cleaver.

Traveling to Rome in search of a cure, he met Sartre and Beauvoir.

Beauvoir wrote, “When one was with him, life seemed to be a tragic adventure, often horrible, but of infinite worth.” Sartre agreed to write the preface to what would be Fanon’s last book, which must have thrilled him: Fanon had told Claude Lanzmann, “I would pay twenty thousand francs a day to speak with Sartre from morning till evening for a fortnight.” Whether Sartre’s preface helped Fanon’s long-term reputation is another matter.

Hannah Arendt was the first to point out that the book’s most famous claim—that violence is a necessary part of anticolonial liberation—is far more strongly stated by Sartre in his preface than by Fanon himself. Fanon did write that violence can désintoxiquer, but Shatz argues that the word is often misunderstood; when translated as “cleansing” or “healing,” the implication that violence itself intoxicates is ignored. “Fanon’s more clinical word choice,” he writes, “indicates the overcoming of a state of drunkenness, the stupor induced by colonial subjugation.” In a blow that must have stung at the time, Arendt quotes Sartre’s glorification of violence as sentences “Marx never could have written.” Were they true, she continued, revenge would be the cure-all for most of our ills.

Fanon drew on his experience treating patients on both sides of the Algerian War to describe the traumas that violence creates for both victims and perpetrators. The final chapter of The Wretched of the Earth betrays profound uncertainty about the healing powers of violence. His claim that anticolonial violence is necessary to disintoxicate remains just that, a claim without an argument, or even a suggestion of how such a process might work—something we’d expect from a thinker who so acutely analyzed other psychological processes created by colonialism. Fanon always regretted that the enslaved West Indians in his native Martinique had waited to have freedom bestowed by France’s 1848 decree of abolition rather than liberating themselves like the Haitians.

Shatz believes that this regret fueled his support of violence as a revolutionary necessity.

Fanon’s sole argument for the redemptive power of violence is his use of Alexandre Kojève’s lectures on Hegel, which captivated listeners in 1930s Paris and profoundly affected existentialism. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit describes the beginning of history as a meeting between two men prepared to fight to the death for recognition. The one who blinks first becomes the slave of the other, who was willing to risk his life for the triumph of spirit. But might Sartre and Fanon have missed the point of the master–slave dialectic that Hegel saw as the motor of history? In “The Black Man and Hegel,” a section in Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon writes that the Black man who has not fought for freedom does not know its price. Sekyi-Otu calls this a willful misreading of Hegel, and as Fanon recognizes in a footnote, the slave’s work can also lead to liberation. In Hegel’s story the master is unhappy, for the recognition he sought can only come from an equal; the vanquished subject cannot fulfill his desire. The slave’s triumph may come later, but it’s also deeper. Forced to toil, he uses his mind to form matter and thus takes part in creation, which brings him closer in spirit to the Creator than the master who enslaved him. Not violent struggle but labor moves history forward—just as it was mass civil disobedience, not the terrorist violence depicted in Gillo Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers (1966), that finally led to the liberation of Algeria. At the very least, Shatz argues, Fanon’s famous praise of violence is ambivalent, however often it’s repeated by the postcolonial left.

What’s not ambivalent is Fanon’s rejection of every form of racism, and the two are connected. “Racism, hatred, resentment and ‘the legitimate desire for revenge’ cannot nurture a war of liberation,” he explains in The Wretched of the Earth. The book was written in the light—or the shadow—of his growing dismay at the corruption, violence, and despair that were surfacing in postcolonial Africa. But his fundamental convictions had already been clear nine years earlier in Black Skin, White Masks. Those who wish to hijack Fanon for a program of Afropessimism, or any other form of twenty-first-century Négritude, must explain away lines like these, from the final chapter of that book:

Haven’t I got better things to do on this earth than avenge the Blacks of the seventeenth century?

I do not want to be the victim of the Ruse of a black world.

My life must not be devoted to making an assessment of black values.

There is no white world; there is no white ethic—any more than there is a white intelligence.

Am I going to ask today’s white men to answer for the slave traders of the seventeenth century?

Am I going to try by every means available to cause guilt to burgeon in their souls?

I am not a slave to slavery that dehumanized my ancestors.

Without clichés, strained metaphors, or false starts, Shatz’s flowing prose makes the radicality of Fanon’s claims look like common sense. The Fanon we encounter in his pages rejects every form of racial essentialism and envisions a future in which “savage self-interest is [not] the sovereign principle of human conduct.”

His target is neither the West nor the Global North but all attempts to divide us through counterfeit categories in order to convince us that politics amounts to tribal struggles for power.

Shatz’s portrait of Fanon does what superb biographies always do: send the reader back to the original texts. They provide a startling challenge to that recent antiracist ideology that routinely dismisses appeals to universalism as intellectual imperialism, fraudulent attempts to impose European ideas on non-European peoples. The versions promoted by Ibram X. Kendi or Robin DiAngelo may be simplistic, but their simplicity and success lay bare assumptions also held by more thoughtful writers. The very expression “identity politics” assumes what is never proven: that our identities are most fundamentally determined by aspects of our selfhood over which we have no control. The inherited victimhood, or perpetratorship, that much current antiracist literature presupposes is just what Fanon sought to renounce.

Shatz invites us to consider Fanon’s work as a meditation on the absurdity of racialization and as a vision of existentialist humanism that could free us from the racial and colonial histories of the past. But we live at a time when some may ask if Shatz’s reading of Fanon is an act of cultural appropriation. Might not a left-leaning white American Jew be naturally inclined to downplay those elements in Fanon’s work that emphasize the uniqueness of Black experience? The Wretched of the Earth, Sartre’s preface claims, is not addressed to us. Doesn’t a universalist reading of Fanon risk dismissing the aspects Europeans find most disconcerting? And isn’t universalism itself a construct designed to veil the imposition of European values and institutions on the rest of the world?

Common as it is today, that claim was never made by Fanon. His fury at the ways in which the ideals of the French Revolution were unrealized in the successive republics that proclaimed them never led him to jettison the ideals themselves. Rather, he saw universalism as a promise whose fulfillment must be demanded.

Only the crudest forms of standpoint epistemology would argue that Sekyi-Otu’s Ghanaian roots provide more justification for his reading than Shatz’s East Coast American ones. Sekyi-Otu is a philosopher, and his writing is more technical and less fluid than Shatz’s, but his Fanon’s Dialectic of Experience is an excellent complement to The Rebel’s Clinic. Sekyi-Otu argues that postmodern readings “result in the evisceration of Fanon’s texts: they excise the critical normative, yes, revolutionary humanist vision which informs his account of the colonial condition and its aftermath.” His impetus for returning to Fanon, writes Sekyi-Otu, was “the disasters of the post-independence experience” in contemporary Africa. Reading Fanon in this light, he argues, suggests a path away from

the desolation of the world after independence,…the rights of humanity smothered by the heavy fists of self-anointed founders, and…the dream of community wrecked by class predation and ethnic violence.

Unlike “the Fanon of the postmodernists,” Sekyi-Otu’s Fanon articulated

his account of the colonial condition and its aftermath in the language of human possibilities; a Fanon in whom this humanist vocabulary was by no means an occasional lapse from the sturdy posture of a sophisticated nihilism.

The more one rereads Fanon, the harder it becomes to view him as a standard-bearer for the rejection of allegedly European values—the assumption, as Sekyi-Otu puts it, that he was prepared to “throw out the bruised baby with the bloodied water.” And the final chapter of Black Skin, White Masks cites the philosopher commonly decried today as a prime exponent of racism and colonialism:

It is not the black world that governs my behavior. My black skin is not a repository for specific values. The starry sky that left Kant in awe has long revealed its secrets to us. And moral law has doubts about itself.

Given all the evidence that Fanon’s goal was, according to Sekyi-Otu, “not the death of the colonizer, but the death of race as the principle of moral judgement,” what accounts for the persistence of the racial reductionist reading? One answer is quite general: tribalism is the simplest form of social organization. It takes an act of abstraction to become a universalist; to see the possibility of common dignity in all the weird and gorgeous ways human beings differ is an achievement we’ve forgotten how to celebrate.

But there’s a concrete historical reason why our age is more comfortable with postcolonial theory than with the history and theory of real anticolonial struggles. The latter cannot be understood without understanding why communism appealed to millions of thoughtful, decent people. For many today, the question is harder to answer than it was during the McCarthy era. Back then, most people knew someone who might admit to sympathy for communism, or at least who spent nights wondering which version of socialism could be the answer to Stalinism. It was possible to put faces and voices on words like “communist,” which now evokes rigid apparatchiks or brutal gulags.

Around the turn of this century a fierce debate over the relative defects of fascism and communism took place in many countries.

There were arguments comparing philosophical foundations, numbers of deaths, and the importance of the intentions or the personal qualities of Hitler and Stalin. Without deciding those questions it’s possible to argue that Stalinism was the greater of two great evils. It’s no surprise, after all, that a barbarous ideology like fascism, built on pursuit of tribal power, should have barbarous consequences. It’s much harder to understand how a movement that began, as Sekyi-Otu writes, with the promise of fulfilling “humanity’s perennial dream of radical justice” led to brutality and terror. The Soviet Union’s betrayal of the principles that led so many to defend it rendered the principles themselves without a home.

Stalin’s gulags no more undermined socialist ideas than the Inquisition undermined Christian ones. But after all was said and argued, what was lost at the end of the millennium was less any principle in particular than the very idea of acting on principle itself, at least on much of a scale. The belief that we have a perennial yearning for radical justice gave way to the neoliberal assumption that the common goal we’re most likely to share is the acquisition of the latest iPhone. As Margaret Thatcher put it, “Economics are the method: the object is to change the soul.”

Maintaining a socialist vision that allows rival social agents upon whom history has visited different scars to pursue common ends is far more demanding than resigning ourselves to tribalist power struggles. When the process of racial reckoning has become a way of avoiding genuine historical reckoning, that vision has been mocked and buried. As Thomas Piketty explains:

When people are told that there is no credible alternative to the socioeconomic organization and class inequality that exist today, it is not surprising that they invest their hopes in defending their borders and identities instead.

It’s a paradox in search of analysis: even as Stalinist repression sabotaged the Soviet Union, communism was often on the right side of history. While acknowledging that its interests were often instrumental, Edward Said wrote:

Nearly every successful Third World liberation movement after World War Two was helped by the Soviet Union’s counterbalancing influence against the United States, Britain, France, Portugal and Holland.

The reluctance to see anything emancipatory in twentieth-century communism has recast many thinkers who supported its ideas as the nationalists they never were. Fanon is not alone here; W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson are celebrated for their fights against racism, but their internationalism is quietly ignored. All three supported that internationalism with the basic principles of socialist theory, though only Du Bois actually joined the Communist Party. In hindsight, Stalin’s attempt to establish socialism in one country underlined the fact that socialist and internationalist impulses share the same roots. Those who refuse to acknowledge anything of value in the history of socialism are thus left preferring tribal identities—however reactionary or fanatical—over universalist ones that might contain seeds of socialism. We’ve yet to recover from US support for the Taliban or Benjamin Netanyahu’s support for Hamas, and we’ve certainly yet to learn from it.

Though schooled in the Marxist theory any leftist thinker of his time had to know, Fanon never joined the Communist Party. But its ideas influenced him profoundly, and they remain a greater challenge to our current politics than the racialist nationalism inherent in the postcolonial oppositions of “Global South” and “Global North.” Many would rather accept the Sartrean version of Fanon, even if it means accepting that “to kill a European is to kill two birds with one stone…leaving a dead man and a free man.”

Said said that Fanon’s radical hopefulness freed him from Michel Foucault’s relentless pessimism. But Shatz is right to end by asking whether Fanon was naive to hold out hope for a radical universalism that avoided the hollowness of the French (and American) versions. Fanon, he reminds us, lived in more hopeful times: the early successes of decolonization and the American civil rights movement could easily appear as the beginning of a universal liberation we no longer know how to imagine.

Yet what if we could return to Fanon’s vision? For what he proposed was not only a robust and radical universalism but also an end to colonialism—to the assumption that it’s natural to base international relations on inequalities of power, which has plagued us since recorded history began. The proposal was idealistic enough in Fanon’s day; it will seem utopian in ours. But honestly, look around you: What do we have to lose?

______________________________________________

Read More:

Susan Neiman is director of the Einstein Forum in Germany. The expanded paperback edition of her book Left Is Not Woke was published in April. Her first work of fiction, Nine Stories: A Berlin Novel, will be published in 2025.

Tags: Activism, Africa, Biography, Colonialism, Colonization, Europe, Frantz Fanon, History, Literature, Marxism, Political Science

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.