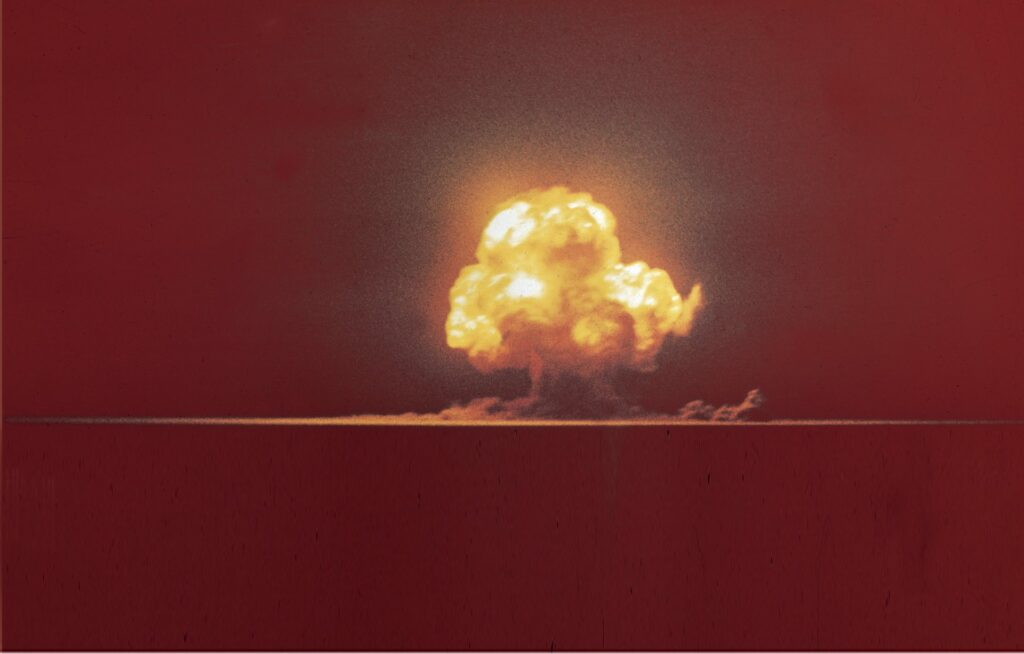

Nuclear War: Still Unthinkable?

IN FOCUS, 10 Jun 2024

Michael Brenner – TRANSCEND Media Service

The United State’s provocative actions are the principal reason the “unthinkable” possibility is becoming ever more likely.

8 Jun 2024 – The unthinkable is becoming thinkable. Nuclear war. The United States’s provocative actions are the principal reason. Desperate to remain the global supremo, our foreign affairs elites are embarked on an increasingly dangerous venture. Going mano a mano with China and Russia in a vain attempt to preserve its hegemonic standing against the tides of history, America is endangering itself and the rest of world. With conflict scenarios that envisage the prospects of war between nuclear armed powers all the rage, some sober reflection is in order. Here are a set of facts about nuclear life worth considering.

I.

The advent of the nuclear age forced a fundamental change in how we think about war and strategic confrontation. By the late 1960s, nearly all thoughtful, responsible persons had come to accept two key intersecting precepts. 1) The sole utility of nuclear weapons is to deter another power similarly endowed – taking into account political as well as strictly military considerations. 2) Risk calculations in dealings between nuclear powers point to the conclusions that opting for a policy choice that entails even a 1-2% chance of leading to the detonation of nuclear bombs should be excluded since the negative value of that occurrence is infinity. That logic also pertains to so-called Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNWs) since their use for war fighting on or near the battlefield carries a high risk of escalation. Inexorably, the theater of operations will extend deep into rear echelons. Population centers will not be unscathed. There is no clear breakpoint on the escalatory ladder..* Understandably, ultra caution has been taken to avoid facing high stakes choices that could raise that option.

In recent years, those tenets implicitly have been modified by officials and analysts. Lacking the experience of managing the delicate relations between the super powers during the Cold War; believing that a new strategic day dawned when they themselves engaged major international issues; emboldened by the triumphalism that prevailed post-1991 to think that the United States ran the world; their notions about nuclear matters deduced from dogmatic, overarching geo-political objectives; and stung into an aggressive, pro-active approach to foreign policy by the passions of 9/11 – they have come to discount the apocalyptic dangers intrinsic to nuclear weapons. They are prone to ignore the acquired wisdom that you don’t play games when nuclear weapons potentially are involved, you don’t bluff, you don’t bet that the other party is bluffing, you avoid wishful thinking like the plague, and you assiduously resist the blandishments of the fantasy worlds that nowadays are a readily available temptation. Yet, today, there are influential people doing all of those things.

II.

There is much handwringing in Washington over the security ties being knit between Russia and North Korea. They have earned Pyongyang a place in the latest version of the Axis of Evil: Russia-China-Iran-North Korea. Heady company for the isolated state in the remote Northeastern corner of Asia. Already it is seen as an immediate threat to the United States due to its expanding nuclear capabilities combined with implacable antagonism. The established wisdom is that the military embrace of Moscow along with the renewed association with China deepens the danger we face and raises the urgency to do something about it.

However, on reflection one can persuasively argue that a North Korea that is coming out of the cold to engage in exchanges with Russia and China is a positive development that should be welcomed. The starting point for such a contrary judgment is a specification of what exactly it is that we have feared from North Korea. Obviously, the technical capability to strike the continental with nuclear weapons constitutes an existential threat. How and why, though, might that latent threat be actualized? The Kim regime has been called a rouge state in the grip of a quirky tyrant whose behavior is unpredictable. Moreover, he is allegedly paranoid. Might he not interpret words or deeds by Washington – perhaps in conjunction with those emanating from Seoul – as signaling a planned attack by his avowed enemies? Therefore, shouldn’t we worry about a rash decision to preempt by launching his ICBMs? There is the further possibility that he becomes totally unhinged and lashes out impetuously in a suicidal dernier cri.

In either of these worst-case scenarios, the chances that the conjectured actions will occur are increased by North Korea’s – and Kim’s – extreme isolation at a political and personal level. It follows that the more that it/he is engaged with other powers and leaders the better. They have a surer grip on reality. They are fully aware of the grave risks inherent in any confrontation with the U.S. They can differentiate between real and imagined threats to North Korea’s security. They potentially can serve as moderators of angst and mediators between North Korea and its enemies.

There is another, practical benefit from Russo-Korean cooperation in the nuclear domain. The Russians likely are providing technical advice on command-and-control mechanisms. Such mechanisms as Permissive Action Links (PALS) play a critical chance in minimizing the risks of accidental or unauthorized activation of nuclear weapons. Everyone has an interest in securing them. That is why the United States clandestinely assisted France in installing such mechanisms in the early 1960s on its embryonic nuclear arsenal even while it publicly distanced itself from its development.

The matter of Moscow-Pyongyang security cooperation has to be placed in a wider strategic context. Collaboration among all four members of the Axis of Evil II has been encouraged by America’s deep hostility toward all four of them. An easing of the mounting tensions between Washington, on the one side, and Russia/China, on the other, would facilitate more transparency and mutual understanding of all parties’ nuclear plans. Actual military conflict, though, increases the chances of escalation to the nuclear level; in that event North Korea could become the wild card complicating the challenge of crisis management.

The pervasive attitude toward dealing with North Korea is that any agreement is just not in the cards due to Kim’s truculent antipathy. Recent history does not support that proposition, though. In fact, two tentative agreements were negotiated: first under the Clinton administration in 1994, then under Trump. The former unraveled mainly because of Washington’s dilatoriness in meeting its commitments. The latter fell victim to the machinations of the security ‘deep state’ that torpedoed a nuanced accord worked out in the meeting between Trump and Kim in Singapore in 2018. It laid out a series of reciprocated steps to be taken in stages. Yet, within just a few weeks it was rendered moot by unilateral American declarations that North Korea must execute its undertakings before any American reciprocation could take place. The agreement initialed by Trump had been fiercely opposed by National Security Advisor John Bolton and other senior officials. They simply imposed their own judgment on a distracted, feckless President.

III.

To the extent that we take seriously the technical and psychological requirements for deterrence, the logic tells us that the strategy most effective for deterrence is the one that you absolutely do not want in place in the events of hostilities.

Example: a tripwire or doomsday mechanism. Works wonderfully as deterrence, but… That’s why the development of Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBM) was such a boost to stable deterrence.

Two things deter: certainty of retaliation; and total uncertainty (e.g. Your opposite numbers state of mind). Certainty can take the form of tripwires: e.g. Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe deployed on the battlefield that almost surely would escalate into strategic, inter-continental exchanges. Certainty could take another form: “launch-on-warning.” That is to say, as soon as incoming missiles are detected – in whatever number, on whatever trajectory – ICBMs and SLBMs are activated and launched. That also obviates the risk that an incoming strike might ‘decapitate’ the targeted government’s leadership – leaving it paralyzed to respond. Knowledge that such arrangements are in place should be the ultimate deterrent to an intentional first strike. However, in the event of an accidental launch or limited launch, you have committed both sides to suicide. The U.S. government never has stated that it has in place any such arrangement that provides a direct link between warning system and release of ICBMs – but there are recurrent assertions that in fact they have existed since Jimmy Carter’s day.

There is a solution to this puzzle: broadcast a lowering of the nuclear threshold but fact leaving intact more conservative contingency plans and force disposition. This seems to be the tactic followed by the Russians. Medvedev repeatedly warns of the prospect that NATO’s further involvement in the Ukraine conflict easily could lead to a resort to nuclear weapons (now reiterated more discretely by Putin), military exercises incorporating TNWs are conducted. Yet there is no evidence that the Kremlin is so rash as to ready itself for a relatively quick resort to nuclear weapons given likely scenarios.

Can the inferior nuclear state deter the superior from launching conventional attacks on it directly? We do not have much data on this – especially since there is no case of the superior state trying to do so. Would an Iran with a rudimentary nuclear arsenal be able to deter an American or Israeli-led assault a la Iraq by threatening troop concentrations and/or naval assets in the Persian Gulf? All we can say is that it will heighten caution. Current example: will the prospect of introducing NATO (American) troops into Ukraine be nullified by fear that, if they are successful, the consequence could be a lowering of the odds on a Russian resort to TNWs? Would either the United States or China be dissuaded from resorting to the nuclear option in extremity when losing a conventional war around Taiwan?

What separates these two scenarios from Cold War crises is that the parties are in direct hostilities. Logically, that should reinforce the already powerful cautionary instincts instilled in the past. However, there are so-called strategists today who seriously conjecture scenarios wherein one plays around with TNWs. Of course, the inescapable truth is that any war with China will obliterate Taiwan. The fate of a few million Taiwanese is given no greater weight in the equation than we do the fate of a few million Ukrainians. If the inferior state (e.g. N. Korea) has the ability to deliver a nuclear weapon against the superior’s homeland, that cautionary element grows by several factors of magnitude.

IV

Can the nuclear state provide a credible deterrent umbrella for an ally that is conventionally inferior to a superior armed enemy? (Western Europe facing the Red Army).

The NATO and South Korea experience says ‘yes.’ That is, if the stakes are highly valued by the state providing the “nuclear umbrella”, e.g. the integrity of Western Europe or Japan. This logic does not apply, however, to a possible NATO/US defense guarantee to a Ukrainian state entity. For it is neither a member of a mutual defense alliance which carries legal pledges and obligations nor a bilateral agreement with the U.S. such as Japan has. Moreover, Ukraine does not possess the same intrinsic importance to the United States.

A related issue arises re. the conjecture that Russia in Ukraine might resort to TNWs in the unlikely event that if it were on the brink of a decisive defeat. Since there is no defense treaty between the Kiev government and NATO – or the U.S. bilaterally – the fear of a nuclear response may be relatively low. Moreover, they have no core security interest at stake. There would be widespread repercussions, though – elsewhere, over time, indirect – that could inflict very significant damage on Russia’s global position, a loss equivalent or greater to whatever occurs in the Ukraine war. Putin’s vague allusion to nuclear weapons properly should be understood not as a threat of possible resort to TNWs, but rather as reinforcing the message that any overt military conflict between nuclear powers (the U.S. and Russia) carries cataclysmic risks. He made that unmistakingly clear in his June 5 press conference in St. Petersburg. Therefore, Washington is warned that it should exclude out-of-hand any notion of armed intervention. The deployment of TNWs in Belarus serves the same deterrent purpose by throwing a nuclear umbrella over a close partner who may be targeted by the West.

Putin addressed the nuclear question in a nuanced manner at his June 5 press conference (Minutes 221 – 223):

What of the nuclear taboo? It didn’t exist at the time of Hiroshima/Nagasaki – for two reasons. The devastating effects of nuclear weapons had not yet been demonstrated; we were in the midst of a total war with Japan. That taboo exists today and will inhibit anyone who is tempted to use nuclear weapons in a compellent mode. However, that taboo has gradually faded in recent years for the reasons outlined in the introduction to this essay.

*TNW is a pronoun with multiple antecedent nouns. There exists a wide range of TNW in terms of explosive force and delivery systems. Those with the lowest yield were configured to be deployed as artillery shells or mines. The exact yields are classified. During the Cold War, the smallest supposedly had a yield of less than 1 Kiloton. However, they have been deactivated for fear that they might wind up in the hands of terrorists. Shells delivered by artillery (e.g. the M777 155mm) can carry yields between 10 – 20 kilotons. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima, ‘Little Boy’, had a yield of 20 Kilotons. The range of the M777 is 20 – 25 miles. Though firing from behind the frontline, that would put those troops at some distance from the detonation with an uncertain degree of protection from blast impact and radiation (the latter depending on the wind direction). Then, one must consider TNW strikes from the enemy who may not be so considerate as to refrain from discomforting you.

There also are neutron bombs in the TNW inventory: explosives engineered to kill living creatures through radiation while causing relatively little blast damage to structures. These details indicate how extremely difficult in would be to limit the effects of their use on or near the battlefield. Realistically, the eventual net effect is likely to be mutual annihilation. The only benefit being an extra few hours or days to prepare oneself to meet one’s Maker. A kinder, gentler Apocalypse.

________________________________________________

Michael Brenner is professor of international affairs at the University of Pittsburgh; a senior fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations, SAIS-Johns Hopkins (Washington, D.C.), contributor to research and consulting projects on Euro-American security and economic issues. Publishes and teaches in the fields of US foreign policy, Euro-American relations, and the European Union. mbren@pitt.edu – More…

Michael Brenner is professor of international affairs at the University of Pittsburgh; a senior fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations, SAIS-Johns Hopkins (Washington, D.C.), contributor to research and consulting projects on Euro-American security and economic issues. Publishes and teaches in the fields of US foreign policy, Euro-American relations, and the European Union. mbren@pitt.edu – More…

Tags: Anti-hegemony, Anti-imperialism, Atomic Weapons, Bullying, China, Multipolar World Order, Nuclear club, Nuclear war, Rogue states, Russia, USA, Unipolar World, Weapons of Mass Destruction

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 10 Jun 2024.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Nuclear War: Still Unthinkable?, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.