Johan Galtung: Positive and Negative Peace

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 29 Jul 2024

Baljit Grewal | School of Social Science, University of Auckland - TRANSCEND Media Service

Introduction

In the present essay, the word peace is the central focus. It is often stated that the word peace is very often used and abused and that since it lacks an agreeable definition and difficult to conceptualise, it is unreal and utopian.

The word peace conjures images of harmony and bliss in psychological, social and political sense. These images seem to conflict with the reality of a chaotic and non-harmonious world. The field of peace research is an attempt to reach towards a world which is peaceful or at least free of violence. Peace Research carries a normative value of striving towards peace, not only in international relations but also in domestic politics. The present essay deals with peace theory and not conflict theory because that is a related but separate branch within peace research.

In this essay, I will describe the differences between two aspects of peace, derived from peace theory and relevant to social and political philosophy, known as positive and negative peace. These terms were first introduced by one of the founders and main figure in peace research, Johan Galtung (1964), in the Editorial to the founding edition of the Journal of Peace Research in 1964. The editorial piece was aimed at clarifying the philosophy of peace research, according to the Peace Research Institute, Oslo who published the journal. The history of the divide between positive and negative peace stems from 195o’s when peace research was too heavily focussed on direct violence, such as assault and warfare and was dominated by the North Americans. The Oslo Peace Research Institute and the journal JPR were a source of fresh insights in peace theory. In the 196o’s, Galtung expanded the concepts of peace and violence to include indirect or structural violence, and this was a direct challenge to the prevalent notions about the nature of peace. The expanded definition of violence led to an expanded definition of peace.

According to Galtung, peace research is a research into the conditions for moving closer to peace or atleast not drifting closer to violence. Thus, negative peace “is the absence of violence, absence of war”, and positive peace “is the integration of human society” (1964, p. 2). It must be noted that in 1964 Galtung did not specifically mention the word structural violence but human integration. Further, these two types of peace are to be conceived as two separate dimensions, where one is possible without the other. Negative peace is what we see in a world dominated by one nation or a United Nations who are equipped with coercive power and readiness to use it, which maybe used to bring about integration (positive peace). Galtung believes that this method is not going to work without general and complete disarmament.

Examples of peace policies and proposals in this tradition are multilateralism, arms control, international conventions (Geneva Conventions), balance of power strategies, and so on. Examples of positive peace policies and proposals include improved human understanding through communication, peace education, international cooperation, dispute resolution, arbitration, conflict management, and so on. Thus, we can see that peace research, from Galtung’s (original 1964 position) perspective, is peace “search” and it values theoretical consistency of norms and values more than empirical validation. In addition, whereas negative peace is shown to be pessimistic, positive peace is optimistic. According to Galtung (1985) the inspiration behind the original positive peace idea was the health sciences, where health can be seen as an mere absence of disease as well as something more positive: making the body capable of resisting disease.

Likewise, two types of remedies obtaining from health analogy are useful for peace research: curative aimed at negative peace and preventive aimed at positive peace. Similarly, the role of peace studies is to study both negative as well as positive aspects of peace, both the conditions for absence of violence and the conditions for peace. In the next sections we will look at what peace theory (as it evolved after 1964) has to say about peace, conflict and violence and their relation to positive and negative peace.

Peace & Violence: Theory & Concepts

The theory of peace has undergone changes since 1964 and Galtung’s views on peace and violence have changed to a broadened focus on the causes and effects of violence and peace. Galtung’s original 1964 position was generally accepted though not without challenges. The main challenges came from critical social theorists who somehow did not agree with the whole peace project. Between 1964-1971 Galtung published many theoretical papers based on his structural theory, along themes such as aggression (1964), institutionalised conflict resolution (1965), non-violence (1965), integration (1968), violence, peace and peace research (1969), structural and direct violence (1971), and, imperialism (1971). One prominent idea that comes out of these papers is that an adequate understanding of violence is required in order to understand and define peace.

So, Galtung moved away from the actor-oriented explanation of peace and violence to structure-oriented explanation where the central idea was that violence exists because of the structure and the actors merely carry out that violence. Galtung (1969) defines violence as being “present when human beings are being influenced so that their actual somatic and mental realisations are below their potential realisation” (p. 168). This definition is much wider than violence as being merely somatic or direct and includes structural violence. This extended definition of violence leads to an extended definition of peace, where peace is not merely and absence of direct violence (negative peace) but also absence of structural violence (positive peace) (Figure 1). Structural violence stems from violence in the structure of society, rather than the actor-generated personal and direct violence.

Figure 1: The Expanded concept of Peace and Violence

By relating violence to the structure of society, Galtung created a connection between peace, conflict and development research. The notion of structural violence is also relevant in conflict theory and development research because its social justice connotations. Galtung goes even further to state that since personal and direct violence are often built into the social structure, it is much better to focus on the bigger picture revealed by structural violence as this would reveal the causes and effects of violence and conditions for peace.

Following from here, the purpose of peace research is to create conditions for promoting both types of peace.

Hakan Wiberg (1981) traced the evolution of the notions of negative and positive peace and is of the view that Galtung expanded the concept of positive peace to include structural violence in his1969 (Galtung, 1969) paper, after Schmid’s (1968) article which maintained that much of peace research is based on negative peace in line with the needs of the power holders and that positive peace is devoid of concrete content. Therefore, peace research serves the purpose of the powerful. Schmid’s line of argument is still prevalent today in some writings, such as Gur-Ze-ev (2oo1) who believe that the entire project of peace education is doomed to fail. Bonisch (1981) also found the positive peace concept lacking in rigour and overly utopian. Galtung (1985) states that the inspiration behind the structural violence idea was Gandhi’s approach to dealing with violence, where the structure of violence was the target of (Gandhi’s) non-violence rather than the actor. Wiberg concluded that the notions of structural violence and positive peace had become well entrenched in peace research even though there were challenges. Primarily as a response to the work of Galtung, the central concern of peace research for many researchers moved from direct violence and its elimination or reduction (negative peace) to the broader agenda of structural violence and its elimination (positive peace) (Weber, 1999).

As the notions of structural violence and positive peace took root in peace theory, Galtung since 198o’s has further expanded the concepts of negative and positive peace to include the notions of social cosmology, culture and ecology. Galtung (1981) presented an argument that the peace concept that dominates contemporary peace theory and practice is the Roman “pax” and it serves the interests of the powerful to maintain status quo in the society.

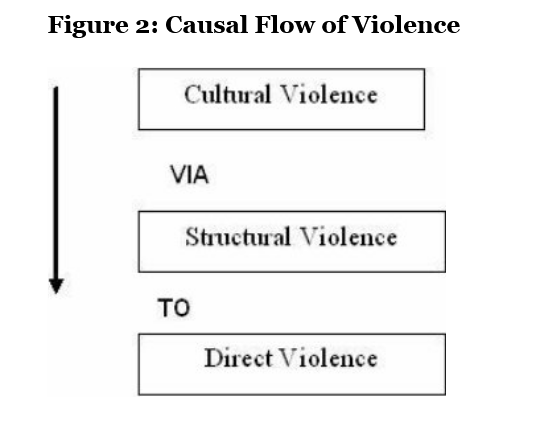

Galtung felt a need for a richer peace concept reflecting the social cosmologies of the world for creating conditions for peace. Another central idea that Galtung (1988) proposed was that peace should be achieved by peaceful means and notions such as just war are basically violences committed by the self-styled leaders of the world. In 199o, Galtung (199o) introduced the concept of cultural violence as those aspects of culture that can be used to justify and legitimise direct and cultural violence. Violence was redefined as “avoidable insults to basic human needs and more generally to life”. Cultural violence was added as a type of violence alongside direct and structural violence. The flow of violence was from cultural via structural to direct violence (Figure 2).

To understand the direct-structural and cultural violence triangle, Galtung (1996) employes the concept of power and identified four dimensions of power impacting positive and negative peace: cultural, economic, military and political. Galtung believes that the vicious spiral of violence can be broken with the virtuous spiral of peace flowing from cultural peace through structural peace to direct peace. This process would bring about positive peace.

Differences between Positive and Negative Peace

The major characteristics of negative and positive peace can be summarised as follows:

Negative Peace: Absence of violence, pessimistic, curative, peace not always by peaceful means.

Positive Peace: Structural integration, optimistic, preventive, peace by peaceful means.

Galtung in most of his work has sought to project positive peace as a higher ideal than negative peace. This is because according to Galtung, peace research shouldn’t merely deal with the narrow vision of ending or reducing violence at a direct or structural level but seek to understand conditions for preventing violence. For this to happen, peace and violence need to be looked at in totality at all levels of human organisation. So, inter-gender violence is no less important than inter-state violence and positive peace promotion has to address issues of violence at all levels. This requires an understanding of the civilisations, development, peace and conflict studied eclectically.

Galtung (1996) suggests a typology in answer to the question, what is the cause of peace? What is the effect of peace? The typology includes six spaces: Nature, Person, Social, World, Culture and Time. This gives five violences: nature violence, actor or direct violence, structural or indirect, cultural and time violence. Negative peace then is defined as the absence of violence of all the above kinds. Positive peace includes nature peace, direct positive peace, structural positive peace and cultural positive. Based on these Galtung comes to the conclusions that violence and peace breed themselves and that positive peace is the best protection against violence.

The answer to the above question can be framed thus, that positive peace is feasible according to Galtung’s theory and that though negative peace is useful for the short term, the longer-term remedies are only achievable with the positive peace approach. After all, prevention is the best cure.

Discussion

The typologies of violence and peace clearly show that Galtung (1996) has modified his previous position. As the criteria for violence has become wider, the achievement of positive peace has become even more illusory. Kenneth Boulding (1977, 1978) has criticised Galtung for downgrading the study of international peace by labelling it “negative peace” and by introducing the notion of structural violence. Boulding believes that such ideas drag peace researchers into theoretical areas (like development studies) where they have little expertise. Kenneth Boulding (1991) attempted to unify these two concepts. Boulding’s idea, which he called “stable peace”, borrowed the notion of the absence of war from negative peace. But Boulding also drew from the positive peace concept. Research on stable peace, he believed, entailed exploring how social systems such as religion or ideology and economic behaviour diminish or increase the chances of movement towards stable peace. While Boulding emphasises on situations where peace is present, Galtung tries to find out where conflict is present, what violences it does and how to achieve positive peace.

It seems that had Galtung not kept on pressing the concept of positive peace, it would have been superseded by the negative peace idea as the central idea of peace research. This would infact have meant the hegemony of the North American dominated conflict resolution paradigm as the dominant paradigm in peace studies. The value of the positive peace paradigm is its vision of bringing about peace rather than just resolving conflicts through political mechanisms. Another idea that comes out of this discussion is that the dichotomy of negative and positive peace might be a false one. But if this dichotomy is not placed at the conceptual level, then the theory of peace will be poorer.

This approach to peace can be seen as very positivist, reflecting Enlightenment ideals. These ideas do not find favour with the postmodernist theorists who believe that these are Western, humanistic, liberal, and enlightenment ideals. Further, postmodern sensitivity to the “contingent stance of values and truth claims; the refusal to accept universal validity claims; and the rejection of any general theory of foundationalism, essentialism, and transcendentalism, are in direct conflict with the Enlightenment’s modern ideals and its philosophical tradition” (Gur-Ze-ev, 2oo1). The postmodern critique is against peace values based on empirical data. On the other hand, the peace theory is constructivist in nature, which means it provides constructive proposals about what should happen and what might work? It attempts to adjust theories to values, producing visions of a new reality (Galtung, 1996). Galtung himself rejects the positivist epistemology in favour of eclectism, where he gathers his conceptual and theoretical mixture by combining Eastern and Western philosophies.

Conclusion

The above essay has shown how the concepts of positive and negative peace have been expanded and reformulated as a response to challenges from their critics. This change has not altered the basic differences between these two concepts, that while negative peace is absence of visible and direct violence, positive peace is emancipatory in nature. Despite the challenges, these ideas remain the foundation of peace theory and are valuable as counter-weight to the realist theory of international relations, which gives too much credit to the state. Peace has to be worked at and is not easy and resistance from the state is inevitable. The twin concepts are very valuable today when peace studies is evolving from building knowledge about peace to peace training and peace education.

References:

Bonisch, A. (1981). Elements of the Modern Concept of Peace. Journal of Peace Research, 18 (2), 165-173.

Boulding, K. (1977). Twelve Friendly Querrels with Johan Galtung. Journal of Peace Research, 14 (1), 75-86.

Boulding, K. (1978). Future Directions of Conflict and Peace Studies. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 22 (2), 342-354.

Boulding, K. (1991). “Stable Peace Among Nations: A Learning Process”, in Boulding, E., Brigagao, C. and Clements, K. (eds.). Peace, Culture and Society: Transnational Research and Dialogue. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1o8–14.

Galtung, J. (1964). An Editorial. Journal of Peace Research, 1 (1), 1-4. Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, Peace and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6 (3), 167-191.

Galtung, J. (1981). Social Cosmology and the Concept of Peace. Journal of Peace Research, 17 (2), 183-199.

Galtung, J. (1985). Twenty-Five Years of Peace Research: Ten Challenges and Some Responses. Journal of Peace Research, 22 (2), 141-158.

Galtung, J. (199o). Cultural Violence. Journal of Peace Research, 27 (3), 291- 3o5.

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilisation. Oslo: PRIO.

Gur-Ze-ev, I. (2oo1). Philosophy of peace education in a postmodern era. Educational Theory, 51 (3), 315-337.

Hicks, David (1988). “Understanding the field”. In David Hicks, (Ed.). Education for Peace: Issues, Principles, and Practice in the Classroom. London: Routledge, 3–19.

Schmid, H. (1968). Peace Research and Politics. Journal of Peace Research, 5 (3), 217-232.

Weber, T. (1999). Gandhi, Deep Ecology, Peace Research and Buddhist Economics. Journal of Peace Research, 36 (3), 349-361.

Wiberg, H. (1981). JPR 1964-198o. What Have We Learnt about Peace? Journal of Peace Research, 18 (2), 111-148.

– Paper published in 2003 –

____________________________________________________

Johan Galtung (24 Oct 1930 – 17 Feb 2024), a professor of peace studies, dr hc mult, was the founder of TRANSCEND International, TRANSCEND Media Service, and rector of TRANSCEND Peace University. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize numerous times and was awarded among others the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative NPP. Galtung has mediated in over 150 conflicts in more than 150 countries, and written more than 170 books on peace and related issues, 96 as the sole author. More than 40 have been translated to other languages, including 50 Years-100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives published by TRANSCEND University Press. His book, Transcend and Transform, was translated to 25 languages. He has published more than 1700 articles and book chapters and over 500 Editorials for TRANSCEND Media Service. More information about Prof. Galtung and all of his publications can be found at transcend.org/galtung

Johan Galtung (24 Oct 1930 – 17 Feb 2024), a professor of peace studies, dr hc mult, was the founder of TRANSCEND International, TRANSCEND Media Service, and rector of TRANSCEND Peace University. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize numerous times and was awarded among others the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative NPP. Galtung has mediated in over 150 conflicts in more than 150 countries, and written more than 170 books on peace and related issues, 96 as the sole author. More than 40 have been translated to other languages, including 50 Years-100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives published by TRANSCEND University Press. His book, Transcend and Transform, was translated to 25 languages. He has published more than 1700 articles and book chapters and over 500 Editorials for TRANSCEND Media Service. More information about Prof. Galtung and all of his publications can be found at transcend.org/galtung

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Conflict studies, Johan Galtung, Negative Peace, Peace Studies, Positive Peace, Structural violence, Terrorism

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

One Response to “Johan Galtung: Positive and Negative Peace”

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER:

Universal Peace Education for Justice and Peace, Prevention and Remedy of War

By Dr. Surya Nath Prasad – Transcend Media Service

http://transcend.org/tms/2023/10/universal-peace-education-for-justice-and-peace-prevention-and-remedy-of-war/…

Universal Peace Education: A Remedy for All Ills

By Surya Nath Prasad, Ph.D.

https://www.editions-harmattan.fr/livre-universal_peace_education_a_remedy_for_all_ills_surya_nath_prasad-9782140488580-80186.html

UCN News Channel

A Dialogue

Between Dr. Surya Nath Prasad and the Anchor of UCN News Channel on

Universal Peace Education

For Peace, Closure of Hospitals (because All will be free from Diseases), Prisons,

Courts of Law, Police Force, and Military

By Surya Nath Prasad, Ph.D.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LS10fxIuvik