The Poetic Science of the Ghost Pipe: Emily Dickinson and the Secret of Earth’s Most Supernatural Flower

INSPIRATIONAL, 28 Oct 2024

Maria Popova | The Marginalian – TRANSCEND Media Service

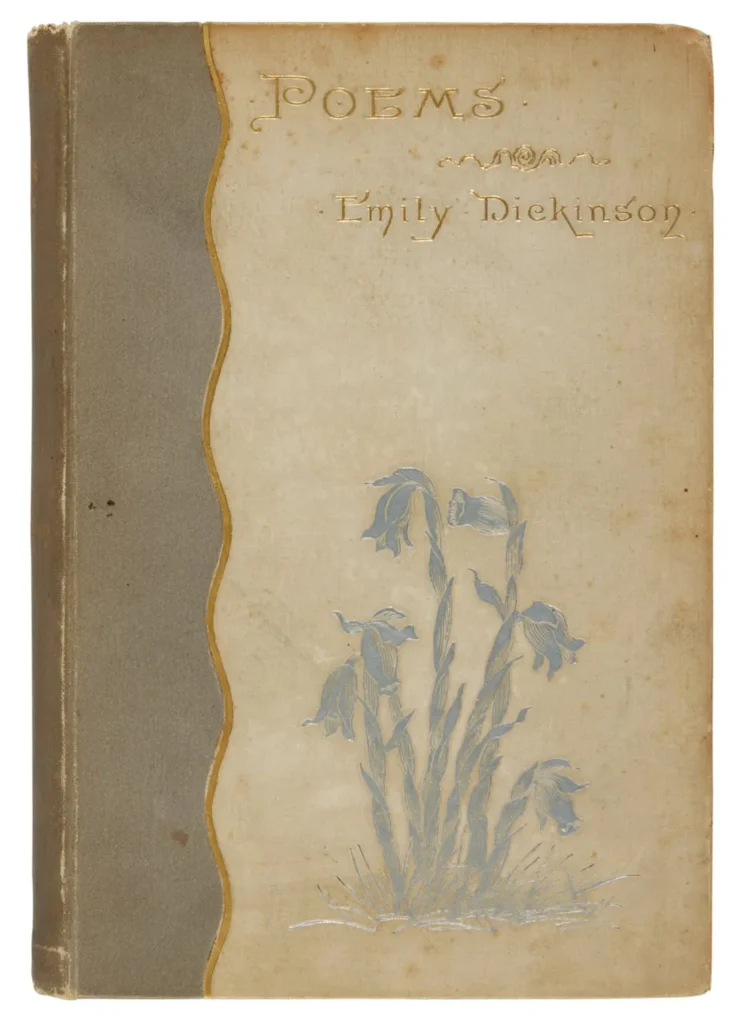

In the late autumn of 1890, four years after Emily Dickinson’s death, her poems met the world for the first time in a handsome volume bound in white. Beneath the gilded title was a flower painting by Mabel Loomis Todd — the complicated woman chiefly responsible for editing and publishing Dickinson’s poems and letters.

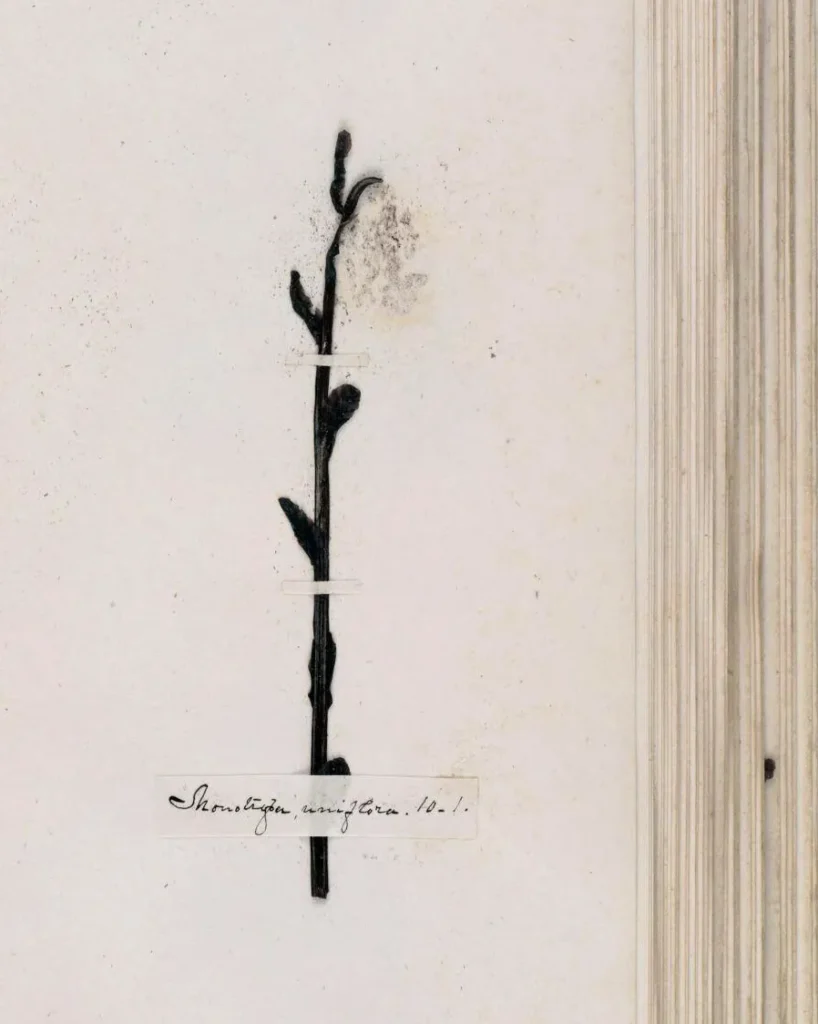

Any flower would have been a fitting emblem for the poet who spent her life believing that “to be a Flower is profound Responsibility,” but none more than this one — a flower she had collected in the woods of Amherst as “a wondering Child,” then pressed into her teenage herbarium and into her poems, enchanted by its “almost supernatural” appearance.

She considered it “the preferred flower of life.”

Monotropa uniflora, known as ghost pipe, is unlike the vast majority of plants on Earth. White as bone, it lacks the chlorophyll by which other plants capture photons and turn light into sugar for life.

Throughout the summer — usually after rainfall, usually under beech trees — the ghost pipe emerges from the darkest regions of the forest floor in clusters, from the Himalayas to Costa Rica to Amherst. Each stem bears a single nodding flower — a tiny chandelier of several translucent petals encircling its dozen stamens and single pistil. Bumblebees, drawn to the pale beauty despite their astonishing ultraviolet vision, are the ghost pipe’s most passionate pollinators.

The secret of Earth’s most “supernatural” flower is its uncommon relationship with the rest of nature:

Rather than reaching up for sunlight like green plants, the ghost pipe reaches down. Its cystidia — the fine hairs coating its roots — entwine around the branching filaments of underground fungi, known as hyphae. So connected, the ghost pipe begins to sap nutrients the fungus has drawn from the roots of nearby photosynthetic trees.

Out of this second-hand survival, such breathtaking beauty.

The mystery of how the ghost pipe flourishes without chlorophyll has enchanted scientists since the dawn of botany. The answer began bubbling up with the discovery of the mycorrhizal network undergirding the forest — a term coined in 1885 by the German botanist, plant pathologist, and mycologist Albert Bernhard Frank, from the Greek mykos (fungus) and rhiza (root). But for nearly a century, the mycorrhizal network — and its relation to the mystery of the ghost pipe — remained a purely theoretical notion, until in 1960 the Swedish botanist Erik Björkman used sugars laced with the radioactive carbon-14 isotope to trace how nutrients move between trees and nearby ghost pipes via the underground fungi.

It was a revelatory notion — an entirely new type of relationship we had never before imagined, as old as the living world.

Less than a century later, we know that 90% of plants rely on these mycorrhizal relationships for their survival — an interdependence for which the English botanist David Read coined the term “the Wood Wide Web,” to describe the groundbreaking research of Canadian plant ecologist Suzanne Simard, who furnished the definitive evidence for it in the 1990s.

By late autumn, the ghost pipe has turned black and brittle. By winter, it has vanished.

“That it will never come again,” Dickinson wrote, “is what makes life so sweet.”

From the brevity and beauty of the ghost pipe’s bloom emerges a tender living poem about the transience of life, about its mystery, about the delicate interdependence that deepens its sweetness.

_______________________________________

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

Tags: Inspirational

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.