Perpetual Peace by Johan Galtung

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 2 Dec 2024

Bishnu Pathak, Ph.D. – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

Perpetual peace is the enduring and positive (state of) peace that exists within individuals, families, and societies. It is a universal law that aims to ensure freedom, justice, vetting, harmony, equity, truth, and reculturation. The goal of perpetual peace is to achieve a state of lasting peace, harmony, and tranquility. Johan Vincent Galtung’s groundbreaking study, “Perpetual Peace,” delves into the concept of achieving lasting peace in a society, nation, and world plagued by conflict, violence, and war. The objectives of this paper are to explain Galtung’s fundamental works in addressing perpetual peace, establish connections between them, and disseminate the outcomes with like-minded individuals and institutions.

This state-of-the-art paper focuses on translating gathered information through experiences and archival literature review using the snowball technique, drawing from the past (yesterday) to understand the axiomatic truth in the present (today), and fostering hope by sharing knowledge of perpetual peace for the future (tomorrow). The study, written with a focus on the “freedom of mind,” is Galtung’s contribution to perpetual peace in theories, practices, peace research, lectures, and mediation sharing. It consists of freedom of liberty, freedom of memory, freedom to apply peace methods, freedom through empowerment, freedom for theories, freedom at mediation, and freedom from conclusion. Medical metaphor is used to analyze the diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of peace methods. The freedom for theories connects to the theory of peace relations, the theory of positive and negative peace, the theory of structural violence, and the theory of the conflict triangle. Perpetual peace by Galtung generally connects with individual, family, society, nation, and beyond values, advocating for change regardless of caste, ethnicity, color, sex, region, profession, knowledge, and community, and shares wisdom and inspiration to fulfill a commitment in resolving conflicts peacefully through mutual respect, diplomacy, dialogue, conciliation, and acknowledgment of collective rights and humanity with a peaceful mindset for universal and inherent peace.

It is a state of tranquility, harmony, and progress that effectively promotes peaceful societies by managing conflicts of varying intensities. Perpetual peace, by Galtung’s study, is two sides of the same coin for the arts of peaceful living. It is studied on the principle of “I know that I do not know” or “I am simply a student for peace and conflict studies,” which allows for ongoing refinement through comments.

Prof. Johan Galtung receives Doctor Honoris Causa from the Complutense University of Madrid, 27 Jan 2017

1. Introduction

In 1795, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant introduced an essay on “Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Essay”, presenting the idea of lasting peace. The concept of perpetual peace was developed in response to democratic peace (Oneal & Russet, 1997), institutional peace (Russett et al, 1998), and business peace (Deudney, 2007). Kant proposed not only a cessation of hostilities but also a foundation upon which to build peace advocating for republican states with a representative government that separates the legislative and executive branches (Smith, 2016). Perpetual peace should not be temporary, like a ceasefire, but should aim for lasting and durable peace.

In 1713, the French scholar Charles-Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre proposed a European confederation project that influenced the 20th century, aiming to establish permanent peace through leagues of nations and a permanent arbitration council based on the peace of Utrecht (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Irenee-Castel-abbe-de-Saint-Pierre). He also suggested an international organization to maintain perpetual peace.

Kant explored the concept of perpetual peace achieved through the establishment of federal states. It is not just the absence of war, but the presence of positive and lasting peace among nations. Perpetual peace involves the establishment of a federation of independent states focused on universal laws to sustain peace, promote cultural exchange, and prevent conflicts among nations. The principles of international law aim to ensure freedom, justice, and equity to regulate state behavior and prevent aggression or conflict. By overcoming the differences between nations and institutions, a more harmonious world can be built. It involves a commitment to peaceful resolutions through mutual respect, diplomacy, dialogue between conflicting parties, and recognition of collective rights and humanity. Perpetual peace leads to peaceful minds fostering protection, promotion, fulfillment, and cooperation among nations.

Praising Bishnu Pathak’s work as a top author and a state-recognized personality in Nepal for peacemaking and perpetual peace, Dr. Narayan Sharma stated that veteran intellectual Yogi Narahari Nath, who introduced the concept of perpetual peace, identifies two types: Shiva Shanti, meaning conscious peace, and Shava Shanti, meaning peace like that of a dead body. China’s communist leader Mao analyzed war and perpetual peace as antagonistic and dialectical relations. He classified war into just and unjust, with a just war leading to perpetual peace and an unjust full war leading to continuous wars (Comments, November 8, 2024).

Gautama Buddha, also known as the Awakened One or Enlightened One (Laumakis, 2023 & Buswell et al.), was born in 623 BC in the sacred region of Lumbini, now located in western Nepal. He spoke about achieving lasting peace, a peace that lasts as perpetual peace (Gethin, 1998 & Strong, 2001). Buddha taught that non-violence, known as ahimsa, is a way of life that leads to perpetual peace (Rakes, 2015). According to Buddha, maintaining perpetual peaceful thoughts leads to peaceful speech and actions (www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/buddha/). The world can only experience perpetual peace if all living beings possess peaceful minds (Tanabe, Fall 2016). In Buddhism, eternal or perpetual peace signifies a state free from suffering and the cycle of rebirth, representing the ultimate goal of liberation from the endless cycle of birth and death (Wilson, 2010). Detaching oneself from the cycle of sukha and dukkha is the key to eternal or perpetual peace and serenity (Monier-Williams, 1899 & Bodhi, 2005).

On November 4, 2024, the co-authored paper outlining the “Perpetual Peace Plan for the Russia-Ukraine War” was published as a Featured Research Paper on TRANSCEND Media Service (TMS). It was featured again on November 11, 2024 due to its significance. This paper garnered more attention from readers than anticipated due to its sensitivity. Currently, there are notable comments available on the TMS website at https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/11/perpetual-peace-plan-for-the-russia-ukraine-war/. Some of the commentators include Dr. Leo Semashko, Dr. Paul Sancheski, Dr Stephan E. Nikolov, Dr. Birendra Prasad Mishra, Dr. Alberto Portugheis, Dr. Christophe Barbey, Dr. Narayan Sharma, among others.

I acknowledge Professor Leo Semashko’s statement regarding the initiation of the Russo-Ukraine war, which began with a coup d’état in February 2014 (BBC, March 5, 2020). We never support extrajudicial killings of any human beings, including the slogan “Destroy Russia and all Russians” in the Revolution of Dignity (Galeotti & Hook, 2019). Anyone who values humanity, respects human rights, advocates for human dignity, and works for human security must adhere to compliance with the International Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Additionally, using children in war and indiscriminately killing them is a war crime, genocide, and a crime against humanity.

The main responsibility of the UN Security Council should be to bring those who commit such crimes against humanity to justice. A crime is a crime whether committed by a powerful organization like NATO or a powerful country or by a small organization or a poor country. I agree with Leo Semashko who stated that we are against the genocide of Russians in Donbass, militarily destroying its Russian population and thereby starting a war against Russians and Russia, resulting in the deaths of 15 thousand children, women and civilians by February 2022 (Comments, November 19, 2024).

These comments are praiseworthy, serious, and relevant. They mainly fall into three categories. The first group of commentators are close to Ukraine, its government, and its people. The second group supports Russia and Russians, while some remain neutral with curiosity. I have shared these comments with all the coauthors, but most have remained silent so far except for Dr. Semashko. I am attempting to address these comments here after considering the collective role of the first coauthor.

I found many of Johan Galtung’s teachings and interviews discussing dukkha and sukha. He talks about Nirvana, Vajrayana, Mahayana, and Theravada philosophies (https://tricycle.org/beginners/buddhism/whats-the-difference-between-theravada-mahayana-and-vajrayana/). Similarly, Galtung has great respect, honor, and admiration for ahimsa, perpetual peace, and divine paradise.

Perpetual peace advocates for conflict resolution, transformation, and management through peaceful and prosperous means. It envisions a future where all adopt methodologies of informal-formal and indirect-direct dialogue, diplomacy, negotiation, and compromise to achieve perpetual peace.

The aim of this study is to contribute to a deeper understanding of Professor Johan Galtung and his efforts towards achieving perpetual peace. Achieving perpetual peace requires a transformative shift in thinking and consciousness among individuals and institutions. It is important to incorporate the common understanding of perpetual peace into university curricula and make it accessible to the general public drawing from Galtung’s wisdom.

The overall objective of this innovative paper is to create a reference guide on perpetual peace contributed by Galtung to helps learners become familiar with the concept. The specific objectives of this paper are to explain Galtung’s key works on perpetual peace, establish connections between them, and share the outcomes with like-minded individuals and institutions.

Galtung’s groundbreaking study on perpetual peace aims to provide descriptive and explanatory insights based on the principles of universality, indivisibility, interdependence, and interrelatedness. Information and literature were gathered through networking tracking methods, comments on the Perpetual Peace Plan for the Russia-Ukraine War and exchanges and discussions with relevant institutions and experts.

This state-of-the-art paper focuses on translating gathered information through experiences and archival literature review using the snowball technique, drawing from the past (yesterday) to understand the axiomatic truth in the present (today), and fostering hope by sharing knowledge of perpetual peace for the future (tomorrow). This innovative work is based on personal experiences, enthusiasm, and participant observation accumulated over four-decades, rather than solely relying on theoretical conceptions.

This paper aims to provide insight into perpetual peace by Galtung for anyone interested, including employees of peace related organizations, academicians, mediators, facilitators, negotiators, students, researchers, policy-makers, and the general public.

The paper also explores the principles and theoretical concepts of human security. Human security is a comprehensive concept that includes freedom from want, and fear, the ability to live with dignity, freedom to act on one’s behalf, and inheriting a healthy environment for future generations as fundamental rights (Pathak, September 2013). Human security is seen as inherent, inalienable, interdependent, multidimensional, and non-derogatory, with human rights at its core (Pathak, March 2014).

Human security shifts from a territorial-centered approach to a people-centered, job-centered, resource (delivery)-centered, service-centered, autonomy-centered, freedom-centered, secular-centered, solidarity centered, nature-centered, humanitarian-centered, and legal-centered approach. It aims to protect individuals from poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, armed conflict, and terrorism, which are essential for achieving success and ensuring perpetual peace worldwide (Pathak, 2013). Therefore, this paper is written with a focus on “freedom in mind,” emphasizing human security.

The subheadings below have been created based on the gravity of the situation and my personal experiences, rather than existing literature. Therefore, I ask readers to consider the significance of each subheading, my feelings, my understanding and how they relate to the title.

2. Freedom of Liberty

Freedom of liberty is a fundamental individual right that guarantees individuals the ability to act and make choices without external or internal restrictions, interference, or control from others. It is the freedom to express oneself and pursue one’s goals based on one’s values, ethics, and beliefs. Freedom of liberty is essential for a democratic society and the protection of personal rights. Without freedom of liberty, a person cannot develop, progress, grow, and thrive as they wish. It is a cornerstone of democracy and individual rights must be protected, upheld, and safe guarded to achieve perpetual peace.

I have chosen Professor Johan Galtung’s contributions to collectively respond to some of the comments on the “Perpetual Peace Plan for the Russia-Ukraine War”. In today’s contemporary world of peace conflict studies, it seems that there is no other academician on this earth who has contributed more than him. Galtung is synonymous with peace studies, peace research, peace journalism, mediation for peace, dialogue with people, conflict transformation, and equity (Rosa, October 21, 2024 & Lynch, July 29, 2024). His introduction of conflict transformation is to change the differing perceptions of individuals, communities, and parties on conflicting relations and events by adopting a win-win approach through collaboration (Galtung, 1996).

He has been involved as a mediator in over 150 conflicts worldwide (Kraemer, March 25, 2024), ranging from “A” for Afghanistan to “Z” for Zimbabwe. He has written 160 books on peace and conflict studies, along with over 1600 articles, and book chapters in his seven decades of perpetual peace work. Some of his books have been translated into over 34 languages, including Nepali. Galtung has addressed questions of perpetual peace for and with whom (Burak, January 2021).

TRANSCEND International, founded by Johan Galtung and Fumiko Nishimura in 1993, is a global peace network aimed at transforming conflict. It connects over 500 mediators, peace workers, and researchers in over 100 countries. The TRANSCEND peace method (Galtung, August 24, 2024), developed over 50 years of research and practice, consists of three main steps: (i) dialogue with all conflict parties directly and indirectly; (ii) distinguish between legitimate goals and illegitimate goals, in which legitimate goals affirm human needs and illegitimate goals violate human needs, and (iii) bridge the gap between legitimate and illegitimate goals embody creativity, empathy and nonviolence and building a new reality (https://www.galtung-institut.de/en/home/johan-galtung/).

Established in 2002, TRANSCEND Peace University (TPU) is an all-online institution led by Johan Galtung, a key pioneering figure in the academic field of peace studies and perpetual peace. The faculty members include renowned peace scholars, peace researchers, and internationally acclaimed mediators. The interdisciplinary courses place a strong emphasis on solution-oriented methodologies. The goal of TPU courses is to provide students with the knowledge and abilities needed for professional perpetual peace and development. TPU gives students the intellectual and practical competence in conflict-transformation and resolution (https://www.transcend.org/tpu/).

He founded the “Journal of Peace Study”, an academic publication dedicated to peace study, in 1964. The Right Livelihood Award, commonly referred to as the “Alternative Nobel Prize,” was given to Dr. Galtung by its Foundation in 1987 in recognition of both his scientific contributions and his role as a crisis and conflict mediator. Galtung co-wrote Gandhi’s “Political Ethics,” his first scholarly work, with his instructor Professor Arne Naess in 1955 (Scharmer, February 21, 2024). He was a pioneer in introducing Gautam Buddha’s dukkha and sukkha and codifying Gandhi’s ideas about non-violence and conflict management.

One of the roots of his lifelong commitment to perpetual peace was witnessing his father’s arrest by the Nazis when he was just a 12‑year old boy. At the age of 21, he became a conscientious objector, choosing to do a year of civilian service instead of military duty. He was willing to serve the additional 6 months required of those who opted for civilian service, but only if he was allowed to work for peace. Unfortunately, his request was denied by the Norwegian government, and he was imprisoned along with murderers and other violent criminals for six months (Pathak, February 11, 2013).

He served as the first president of the World Future Studies Federation from 1973 to 1977, and also as the Director General of the International University Center in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia from 1974 to 1977. As a visiting professor, he has lectured at many universities, including Santiago, Chile; Tampere, Finland; Tromsö, Norway; Uppsala, Sweden; Turin, Italy; Alicante, Spain; Soka, Japan; the International Institute for Development Studies in Geneva; Princeton, Hawaii, Columbia and Saybrook; Sichuan; Berlin, Witten‑Herdecke, Germany; Puebla, Mexico; and more (Pathak, February 11, 2013).

For his conflict and peace studies, he adopted a perpetual peace methodology applying medical terminology such as prognosis, diagnosis, and therapy as his ancestors for generations belonged to medical doctors and nurses. “A physician has been born,” a family acquaintance said upon his birth in Oslo on October 24, 1930 (https://www.galtung-institut.de/en/home/johan-galtung/). A doctor is still considered a prestigious societal position in Europe, including Norway, deserving to be the guardians of the health and well-being of all humans.

3. Freedom in memory

Memory is not just a fleeting concept, but a priceless gift that allows individuals to revisit the past, treasure experiences, and learn from their mistakes. It is a vital aspect of identity that molds our sense of self and belonging. Freedom in memories can encompass joyful moments, as well as pain, suffering, trauma, grief, and remorse. In this poignant collection, the author reflects on their initial encounter with Galtung in late November 1999 and the subsequent connection they maintained. The author grapples with these memories, processes them, decides to move forward, and ultimately discovers perpetual peace. By embracing the freedom that memory provides, the author harnesses it as a potent tool for personal growth, healing, and progress in life. Essentially, the author is sharing their recollection with Professor Galtung in the subtitle, alongside a few anecdotes from contemporary scholars worldwide.

A recipient of the Right Livelihood Award in 1987, Galtung was a dedicated peace advocate whose influence extended far beyond national borders. Ole von Uexkull, Right Livelihood’s Executive Director says, “His legacy serves as a reminder of the power of compassion, empathy, and dialogue in resolving conflicts and building a more harmonious world. His tireless efforts to promote non-violent alternatives and address the root causes of conflict have left an indelible mark on the world” (March 11, 2024).

Professor Steven Youngblood remembered that Dr. Galtung was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, and made the short list of 32 individuals considered for the prize, but ultimately did not win. Professor Richard Falk of Princeton University praised Galtung stated that Johan Galtung has been a dedicated warrior for peace, embodying the ideals that it seems to me the Nobel Prize was created to honor. What needs to happened for us “to overcome the war system and enjoy the material, political, and spiritual benefits of living in a world of peace premised on the nonviolent resolution of disputes among sovereign states and respect for the authority of international law” (February 26, 2024).

Future Studies Professor Sohail Inayatullah, a Pakistani-born Australian academic, calls a pivotal movement in his academic journey: “When I submitted my doctoral proposal, he looked at it and threw it in the garbage. He said, ‘You are selling your topic short.’ Instead, he suggested I engage in comparative history and epistemology. From that, my PhD became, ‘Understanding Sarkar: The Indian episteme, Macrohistory, and Transformative Knowledge.’…But his toughness was minor compared to his generosity. When I gave him my 120,000-word thesis, instead of balking at the length, he read a chapter daily and called me every evening with words of congratulation. When others criticized my focus on Sarkar, he simply said, ‘Send them more chapters – they don’t know what they don’t know’ (February 26, 2024)”.

Galtung and I share both an institutional and personal relationship. Before starting my doctoral studies, I had heard of Galtung. Born in 1930, Dr. Galtung witnessed the German occupation of his native Norway during World War II. He has served as a peace mediator in numerous countries worldwide and is affectionately known as the father of conflict and peace studies (Urban, August 5, 2024) for his groundbreaking efforts in introducing the discipline at the university level. Currently, conflict and peace studies are included in the curriculum of over 1000 universities globally.

In mid-1999, after being awarded a DANIDA Fellowship for my PhD, I traveled to Denmark and joined the Danish Center for Human Rights to study the human rights impact of the Maoist-launched People’s War. During this time, I managed to find Galtung’s email address and sent him an email on November 19, 1999. To my surprise, he replied the very next day.

Our relationship continued to develop as we pursued studies in conflict and peace around the world. We finally met in persons in Nepal on May 19, 2003, at a program organized by the National Human Rights Commission at the Himalayan Hotel, Kathmandu. Galtung shared his plans to establish the world’s first online TRANSCEND Peace University with six academicians and asked me if I was interested in being a founding member. Besides TPU, he appointed me as the South Asia regional convener of TRANSCEND International. Anyone wishing to become a member of TRANSCEND in this region had to submit an application along with biodata for approval by Dr. Antonio Rosa, Personal Secretary of Johan Galtung, which strengthened our relationship further.

With 26 conveners, TRANSCEND is currently active in 14 regions around the world. These regions include Latin America, North America, Euro Latina, Europe Deutsch, Europe Nordic, Eastern Europe, CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) including Russia, Africa, Arab World, Middle East, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Pacific Oceania and South Asia. Peace and Conflict Studies Center (PCS Center) in Kathmandu is one of the conveners in South Asia (Pathak, February 11, 2013).

On November 21, Galtung contacted me via email at the Conflict Study Center (CS Center), Kathmandu, informing me of his upcoming visit to Nepal for a mediation sharing session from November 30 to December 2, 2006. He asked me to be a coordinator during his stay and the CS Center organized a mediation sharing program with the support of Chelsea International, Kathmandu.

The CS Center organized a Mediation sharing program at Chelsea International premises on November 30, 2006. Initially, the number of participants was estimated to be around 50 consisting of representatives from UN Agencies/Missions, Diplomatic Missions, Donor Communities, Talks Team Members, Academia, Media, Peace Workers, Young People, members of peace-talks, and others. However, many more people showed up upon hearing that Professor Galtung would be sharing his experiences. The event was unable to control the masses resulting in over 350 participants, including Ian Martin, Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General, Maoist talks team leader led by Krishna Bahadur Mahara, dialogue coordinator Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister Krishna Prasad Sitaula on behalf of the Government of Nepal, dialogue facilitator/mediator Daman Nath Dhungana and Padma Ratna Tuladhar who attended the event.

This time Johan Galtung was coming to Nepal with an invitation and financial support from the Norwegian Embassy in Kathmandu to share his experience and facilitate communication with the Maoists and political parties in Nepal. I voluntarily facilitated all arrangements, from receiving him at the airport to organizing the program. When Galtung was leaving for Tribhuvan International Airport in a car, he expressed his sadness that the Norwegian embassy neither came to welcome him at the airport nor bid farewell there. Furthermore, the embassy officials did not even ask, how he was doing. It was an unfortunate decision taken by the Norwegian Nobel Committee to award the Peace Prize to Kissinger in 1973 and deny the same to their native son – Galtung (Mehdi, November 18, 2024).

He thanked me for making his 4-day program a grand success with just a week’s notice. The program held on November 30, 2024, was memorable not only for the number of participants, but also for the presence of the UN Secretary General’s representative, and almost all foreign diplomatic bodies residing in Nepal, dialogue teams, political parties, dialogue mediators, civil society workers, and academicians.

Galtung encouraged me, saying I was not only an academician but also a good manager. He added that when he started conflict and peace studies, he was not as capable as I was then. He believed that if I continued to work hard, we could reintroduce Nepal, the birthplace of Gautama Buddha, to the world. His words became a guiding light for me, and I have found them to be a blessing in recent years.

Bishnu Pathak’s academic performance in just sixteen days, from August 09 to October 08, 2022

In just 60 days, from August 09 to October 08, 2022, over 100 of Prof. Pathak’s international publications on peace, transitional justice, conflict, human rights, and human security reached 158 universities in 99 countries, as reported by Academia.edu (see below box).

The Constituent Assembly (CA) became defunct on May 27, 2012 without promulgating a new constitution even after four years of its normal and extended tenure. When the process of constitution-making by the CA faced political and legitimacy crises, the PCS Center in Kathmandu reached out to Galtung for help in resolving the crisis within the government and political parties. Galtung arranged his visit from January 9 to 19, 2013, which marked Nepal’s first peace event, during which I once again assumed the role of coordinator. Galtung conducted meetings, discussions, and shared his mediation techniques with various prominent figures, including top-and mid-level political leaders, peace and human rights scholars and activists, civil society stalwarts, media personnel, and academics.

4. Freedom to apply peace method

The peace method is a strategy and set of tactics for transforming and resolving conflict or violence, promoting a harmonious culture, a cooperative society, and healthy relationships. It involves active listening, careful speaking, empathy, and both informal and formal (open) exchanges of sharing, understanding, and communication. The peace method fosters a culture of peace in which individuals can work together to find mutually useful solutions and build strong networks with others involved in conflict. By using the peace method, individuals or institutions can address contradictions, disagreements, differences, and misunderstandings in a peaceful and constructive manner. The peace method aims to achieve a prosperous, harmonious, and conducive environment where the voices of individuals in society are heard and respected. Therefore, it is a simple, yet commanding approach to transforming conflict or violence through peaceful means.

Professor Johan Galtung has presented numerous peace method in conflict and peace studies, as well as principles of mediation, and various metaphors for the peace process. His Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy (DPT) approach, which he developed, clearly reflects his upbringing in a medical metaphor family (Bastola, January 31, 2023). While Galtung frequently uses these terms in his lectures and discussions, understanding DPT in the context of conflict and peace studies can be challenging. The peace method he has developed is complex, particularly when applied to social, political, and rights-based disciplines. Throughout my long association with Galtung, I have attempted to simplify the context of DPT for better comprehension. Below is my attempt to explain this peace method in a simple and straight forward way to apply to conflict peace studies, peace research, and conflict mediation to attain perpetual peace.

A diagnosis using Galtung’s peace tool involves identifying the source of conflict or violence by examining the nature of people’s suffering, the scarcity or misuse of resources in society, and the relevant tools of conflict transformation and violence prevention. A correct diagnosis is crucial for creating an effective perpetual peace plan for transforming conflict. Diagnosis involves considering the history of conflict or violence’s impact on individuals, institutions, and physical infrastructures, as well as its potential future impact. Therefore, diagnosis focuses on the past, as the past can provide the data necessary for descriptive analysis (Galtung, 2000). Diagnosis is understanding why a party is engaging in conflict or violent behavior and actions. Diagnosis is made by recommending appropriate conflict or violence measures to stop it through negotiation and restore normal public life for perpetual peace.

Prognosis is nothing less than early warning and early action to maintain perpetual peace. It is the best estimate or prediction of the outcome of a conflict or violent situation. Prognosis is an essential aspect of conflict resolution or violence prevention, as it helps individuals risk-taking people and victims understand the likely progression of the conflict or violence and make informed decisions about peacebuilding options. Prognosis can vary depending on individual circumstances and specific conflicting factors such as the stage of conflict, people’s suffering, and the effectiveness of available medical, legal, and human rights interventions. People should consult with the appropriate agency for the most accurate and up to date prognosis information in their specific changed context. A prognosis helps identify the source of conflict or violence, reduce it, observe its progress, promote temporary peace, monitor ceasefires, and develop a path towards perpetual peace. It also involves discussions on potential peacemaking and peacebuilding measures. Galtung states, “Prognosis is descriptive, but of future violence, in other words, predictive” (2000). It may explore much similar to reciprocity and violence spirals.

Therapy offers suggestions for reducing conflict and violence worldwide. It is focused on the future as a prescriptive analysis (Galtung, 2000). Therapy is a powerful intervention against conflict or violence, helping individuals address and overcome psychosocial and emotional behavioral issues to achieve perpetual peace. It provides a safe, confidential space, and a conducive environment for conflict-affected individuals, families, and societies to explore their thoughts and feelings gain insight and develop coping strategies for conflict transformation and violence prevention. Cognitive, psychodynamic, and mindfulness therapies are used to address specific individual challenges. Peace therapy prevents anxiety, depression, trauma, and stress resulting from conflict or violence. It enhances personal skills, builds self-esteem, and promotes well-being.

Dr. Galtung later added “therapy of the past” to his approach, which involves exploring counterfactual history to see how violence could have been prevented by taking different actions in the past. What could have been done at that critical juncture (Galtung, 2000).

These three DPT components play a significant role in determining the causes of conflict or violence, as well as in transforming the overall outcome for the individuals, families, and societies affected by conflict or violence. In general terms, the process of determining the source or cause of conflict or violence is known as diagnosis, while the anticipated result of the conflict or violence arising from the discovered cause is known as prognosis. The underlying fundamental cause of the conflict or violence that is either transformed, managed, or resolved is known as therapy. These DPT peace methods are powerful tools to achieve perpetual peace.

5. Freedom through empowerment

Freedom through empowerment is the process of gaining the knowledge, power, and independence to control one’s own life and fulfill desires. Empowerment, which is a process and a final outcome of perpetual peace, can be achieved by a number of tactics, such as applied distinctiveness, technology, team cohesion, access to accurate information, and changing mindsets. It entails being cognizant of both domestic and global challenges (Berger, 2009). Empowerment makes decisions easier, fosters respect in families and communities, and gives people the confidence to resolve and transform problems or conflicts (Government of India, Undated). Gaining skills, being more self-assured, independent, and capable of handling conflict are all ways to achieve freedom through empowerment. The ability to promote accountability, take part in public discourse, and participate in democratic peace processes is freedom through empowerment.

Under the dynamic leadership of Professor Johan Galtung, the TRANSCEND Mission to Nepal conducted a nine-day Peacebuilding and Conflict Transformation training program from December 3 to 12, 2002. The program was attended by GTZ staff from Germany and GTZ Nepal, and was administratively, technically, and financially supported by GTZ. TRANSCEND, with assistance from PATRIR, also conducted a five-day advanced training program on Peacebuilding, Conflict Transformation, and Global Development, led by Kai Frithjof Brand-Jacobsen in June 2002. This program was initiated in 2001 as a foundation through a series of intensive discussions and dialogues on Peacebuilding and Conflict Transformation in Nepal with relevant actors and institutions (Brand-Jacobsen, January 7, 2003).

Professor Galtung enthusiastically supported the idea of creating a separate think tank the Global Governance Institute in the center of Europe in Brussels. This think tank served as a platform for reexamining burning issues, such as peace, security, and intercultural perspectives, with a focus on engaging younger generations by bringing together early career researchers, senior scholars, and practitioners. Professor Galtung encouraged the founding team of scholars to reconsider a number of presumptions by spending a great deal of time and effort meeting with students (Global Governance Institute, February 19, 2024).

He established the world’s first International Peace Research Institute in Oslo in 1959 (https://www.prio.org/news/3505 & Haavelsrud, et al., March 11, 2024) which has been a landmark in the institutionalization of peace research (Bilgin, 2018). In 1956, Galtung earned his PhD in mathematics, followed by another PhD in sociology in 1957 (https://www.galtung-institut.de/en/home/johan-galtung/). Research Professor Nils Petter Gleditsch of PRIO writes,

“He was a person of exceptional energy. After qualifying for university in two subjects, he completed two simultaneous master’s degrees (in statistics and sociology), and went on to hold professorships in several fields and countries. In his younger years, he signed the manifesto for Aksjon mot doktorgraden (a campaign against Norwegian doctoral degrees), but later received honorary doctorates from various universities” (February 17, 2024).

Galtung served as the director of the PRIO institute until 1969. He was then appointed as the world’s first chair in peace and conflict studies at the University of Oslo in 1969. Under his direction, the Norwegian Ministry of Education provided funding for PRIO to become a stand-alone research facility (Sandy, Undated). Additionally, Galtung played a key role in naming the first Tun Mahathir Professor of Global Peace at the International Islamic University in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, where he also helped establish the Peace Department (School of Public and International Affairs, November 17, 2015).

He later served as the director general of the International University Centre (IUC) in Dubrovnik and helped to found the institution where he served as its first Director General (https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/SForum/SForum2012/Biographies_27092012.pdf). Galtung was involved in founding the World Future Studies Federation (WFSF), established in Paris in 1973. The WFSF aims to address complex, competing, and conflicting issues by promoting long-term thinking in institutions such as government and other policy areas and to embrace domain to cultural pluralism (https://wfsf.org/history/).

Galtung contributed as the project coordinator at the United Nations University in Geneva for four years (1979-1981) and as a Special Consultant at the Second Special Session on Disarmament (U.N. 1981). He has worked as a Consultant for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), World Health Organization (WHO), UN Environment Program (UNEP), UN 100, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations Organization (UNO) and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation, 1993).

Galtung has earned a name and fame as a world-renowned peace scientist and is affiliated with many universities around the world. He has been a visiting professor at several Universities, including the University of Essex, England (1967-1969), International Christian University, Tokyo, Japan (1970), University of Cairo, Egypt (1971), Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India (1971), University of Zurich, Switzerland (1971-72), University of Hawaii, Honolulu (1973), Royal Academy of Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark (1976), Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris (1979-81), University of West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad (1981) and Freie Universitat Belin, Germany (1983) (Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation, 1993).

Johan Galtung co-founded the International Peace Research Association (IPRA) in 1964. Throughout his career, Galtung has made significant theoretical contributions on perpetual peace, social justice, and humanity (Vision of Humanity, Undated). In order to combat the sickness of violence, Galtung himself put forth a vision for the future: alternate territorial and non-territorial systems that can easily come together in cooperative circles through perceptual peace rather than competition and war-mongering (https://jfsdigital.org/category/authors/johan-galtung/).

6. Freedom for Theories

Freedom for theories is a fundamental principle of intellectual and academic discourses. It allows individuals to explore and develop diverse perspectives and new ideas without fear of censorship, harassment, prejudice, or limitation. It is nothing less than a cornerstone of intellectual freedom and creativity. Embracing freedom for theories fosters a culture of open-mindedness and critical thinking, leading to an advancement of knowledge and understanding. Freedom for theories empowers individuals to challenge century-old beliefs and question leaders and authorities. Without freedom for theories, there can be no progress or growth in discoveries in the academic world. It is essential that we protect and uphold this freedom in order to promote innovation in various fields of study that significantly contribute to the progression of knowledge, impacting society, nations, and beyond, both now and in the future.

6.1 Theory of peace relations

Galtung discuses perpetual peace as a relationship.

Perpetual peace is not a characteristic of one party alone, but a quality of the relationship between parties. Galtung outlines three types of relations: (i) Negative, inharmonious: where what is detrimental to one is beneficial, but not to the other, (ii) indifferent: a lack of relationship where parties do not care about each other, and (iii) Positive, harmonious, where what is beneficial to one is not also useful to the other (Galtung, Undated).

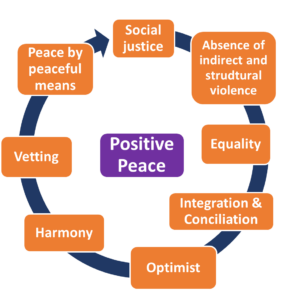

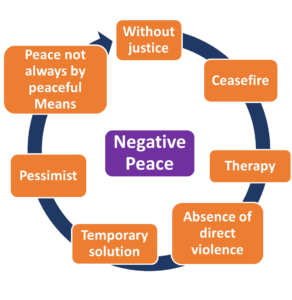

Studies on negative peace focus on reducing or eliminating negative relations, while studies on positive peace aim to build increasingly harmonious relations. Violence studies, on the other hand, focus on understanding the capability to inflict harm. Negative perpetual peace refers to the absence of violence, while positive perpetual peace involves the presence of harmony, whether intentional or not. These two types of perpetual peace are as distinct as negative health (the absence of illness symptoms) and positive health (feeling well and having the capacity to handle illness) (Galtung, Undated).

6.2 Theory of positive and negative

Dichotomous positive and negative peace refer to two different concepts in the realm of peace studies (Gallardo, February 26, 2024). Positive peace is characterized by the presence of social justice, truth and fact, vetting, harmony, and equality among individuals, families, communities, and societies. It focuses on addressing the root-causes of conflict or violence and promoting perpetual peace through cooperation and understanding. On the other hand, negative peace is the absence of violence and fear of violence. It is achieved through the use of force without necessarily addressing the underlying causes. Furthermore, negative peace provides a temporary solution to violence and conflict, while positive peace is long-lasting, meaningful, and aims to restore perpetual peace worldwide (Galtung, August 30, 2003; Dijkeme & d’Hères, May 2007; and https://www.visionofhumanity.org/introducing-the-concept-of-peace/).

Johan Galtung: Summary of positive (perpetual) peace and negative peace

Developed by Professor Bishnu Pathak, PhD: December 2024

The box mentioned above was designed and created by the author, who also discussed the key features that differentiate the negative and positive (perpetual) dimensions of peace. Renowned peace theorist Johan Galtung established the fundamental distinction between positive and negative peace.

6.3 Theory of structural violence

The theory of structural violence is an idea that explains how societal structures and institutions harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs, such as accessing essential services and basic rights. Structural violence is a type of violence that occurs when individuals are deprived of achieving their social, economic, political, and legal rights, making it impossible for them to meet their basic requirements (Lee, March 1, 2019). It is also called indirect violence.

The term was coined by Johan Galtung in 1969 in his article “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research”. Structural violence is a form of social injustice and has been elevated to wisdom. Galtung proposed the institutionalization of racism, sexism, and classism in a public lecture at the International Islamic University Malaysia (November 21, 2014). Galtung differentiates structural violence from classical violence, which is characterized by basic, temporary bodily destruction (November 12-15, 1975). Structural violence results in harm, but Galtung clearly defines positive peace as the absence of structural violence (Vorobej, 2008).

Structural violence includes racism, colorism, ableism, classism, income inequality, ageism, heteronormativity, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, fatphobia, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia (Chefalo, March 24, 2023). Therefore, structural violence creates risks and disadvantages for certain poor, marginalized, and vulnerable groups.

6.4 Theory of the Conflict Triangle

Johan Galtung developed the Conflict Triangle theory, also known as the ABC Triangle. This theory examines three aspects of conflict: attitudes, behaviors, and context or contradiction. The ABC Triangle is based on the idea that peace is characterized by the absence of violence and commonly agreed upon societal goals. The three components of the Conflict Triangle are:

Attitudes: As disagreements escalate, the attitudes of opposing parties may become more hostile or defensive.

Behaviors: The actions of the conflicting parties, influenced by their own attitudes and those of others.

Context or Contradiction: The environment in which the conflict occurs (Galtung, 1969).

The Conflict Triangle is a powerful tool for analyzing conflicts and understanding their roots. All three components – attitudes, behaviors, and contradictions – are interrelated and interconnected essential components of conflicts representing discrepancies between the needs, values, and interests involved in the conflict (https://www.linkedin.com/advice/1/how-do-you-apply-conflict-triangle-model-peacebuilding). However, some argue that the triangle may oversimplify the complexity of real-world conflicts, which often involve overlapping and dynamic issues.

7. Freedom at mediation

Freedom at mediation offers a unique opportunity for individuals to work towards resolving conflicts or violence in a peaceful and constructive manner. It provides a safe and neutral environment where parties can openly discuss and express their thoughts and feelings. The benefit of mediation is the freedom it offers. Unlike traditional proceedings in judicial courts and executives where decisions are imposed from above, mediation allows individuals to actively participate in decision-making. Freedom at mediation promotes a sense of autonomy and self-determination. It provides a platform for everyone to exercise their freedom in resolving violence, war or conflict.

Johan Galtung visited Nepal twice, in 1968 and 1986, before the Maoist-launched People’s War. He visited Nepal from May 16 to 20, 2003, to mediate between the conflicting parties, namely the Government of Nepal and the Maoists. Speaking at a talk program on ‘Transformation of Conflict: Human Rights Approach, Dr. Galtung emphasized Nepal’s need for a cultural and social revolution. He recommended achieving an equitable society through proportional representation and a fixed quota system. Prof. Galtung suggested three key actions that have been proposed: constitution amendment, constitution revision, and a new constitution. He said it is important to shift attention and focus from negative to positive peace (Wright et al, October 7, 2024) . He added that it is equally important to move beyond what the political parties have been saying and not to confuse a ceasefire for perpetual peace.

UNDP Resident Representative Dr. Henning Karcher found Dr. Galtung’s theories on direct, structural, and cultural violence convincing and agreed that Nepal’s society is characterized by structural violence. He stated, “While the conflict in Nepal has political, ideological and even geo-political dimensions, its main root causes are social and economic. These are related to frustrated expectations that came with the advent of democracy, abject poverty that persists for a large percentage of the population, poor and inefficient delivery of social services in areas such as education and health, and inequality, exclusion and discrimination” (People’s Review, May 22-28, 2003).

On the topic of conflict formation and contradiction, Galtung emphasized that all human societies are divided by fault-lines in their deep structure, similar to tectonic plates, which can cause “socio-quakes” when they shift. Massive structural violence can arise along these fault-lines, leading to outbreaks of direct violence. He identified eleven fault-lines that were activated:

| # | Fault-line | Issue | Possible Remedy |

| 1 | Humans/Nature | Depletion/pollution | Appropriate technology |

| 2 | Gender | Repression of women | Appropriate representation |

| 3 | Generation | Young people | Appropriate representation |

| 4 | Class: Political | HMG, King | · Parliamentary democracy Constitutional monarchy |

| 5 | Class: Military | Royal Nepal Army | Parliamentary control of army |

| 6 | Class: Economic | Misery, inequality | · Massive uplift from below

· Land reform · Temple land reform |

| 7 | Class: Culture | Strong cooperative, marginalization | · Public and private sectors

· Massive literacy campaign · Sharing of culture |

| 8 | Class: Social | Dalits | · Appropriate representation

· Economic/cultural measures |

| 9 | Nationalities | Dominant culture, unitary state | · Mother tongue education

· Devolution · Soft federalism |

| 10 | Territories | Misery, inequality | Massive uplift from below |

| 11 | Others/Nepal | Intervention | Reconfirm panch shila |

| Adapted from: The Crisis in Nepal: Opportunity + Danger, available at https://www.transcend.org/files/article525.html or https://www.transcend.org/tms/2013/02/nepal-six-years-of-transition/ | |||

Galtung developed a solution oriented Transcend Perpetual Peace Perspective to facilitate mediation in Nepal’s peace process in 2003 and 2006.

7.1 Nepal: A Transcend Peace Perspective

Diagnosis: Three proposals emerged from a mediation exercise in May 2003

The parties, known as SPA (Seven-Party Alliance) require a robust program for social change that invites both the Maoists and the King to participate in roundtable talks, establish an interim government with the Maoists, and revise the constitution. This action could be promoted by public demonstrations and or significant civil society pressure.

- A statement from the Maoists pledging allegiance to parliamentary democracy

- A statement from the King pledging allegiance to constitutional monarchy.

Effective nonviolence on the streets of Kathmandu from April 6 to 24, 2006, resulted in significant changes. People along with Indian pressure, compelled the King to relinquish absolute monarchy and potentially participate in the process while respecting any referendum. However, the current dialogue between the Prime Minister and the Maoist leader is shrouded in secrecy and seems more accountable to India and the USA, rather than the government, people, and parliament (India-USocracy?). The focus is primarily on achieving a cease-fire, disarmament, holding elections for the Constituent Assembly to amend the 1990 constitution, and debating the monarchy versus republic issue, with no concrete program for social change.

Nepal was previously a feudal society with an absolute monarchy. The Maoist rebellion used illegitimate means to pursue 40-point demand legitimate modernizing objectives, which were submitted on February 1, 1996, rejected, leading to the People’s War on February 13, 1996. The King and the Government resorted to illegitimate means to maintain an illegitimate status quo.

Currently, only conflicts that impact elites are taken seriously, focusing on violence control, the legitimacy of parliament/government/head-of-state, rather than addressing social inequalities and widespread deprivation. This focus on elite interests while neglecting the basic needs of the people leads to a lack of synchronicity in the process.

Prognosis: This is a cease-fire process, which is also called a perpetual peace process.

A causal chain stemming from unresolved conflicts, polarization, dehumanization, violence, and trauma necessitates a perpetual peace process comprising four components: conflict resolution through mediation, peace-building, violence control, and conciliation for healing and closure.

These components should be implemented simultaneously as a comprehensive package. Major risks include a cease-fire without conflict resolution potentially reigniting the violence (similar to cases in Israel-Palestine and Sri Lanka) and conciliation without solving the conflict only resulting in pacification. It is crucial to decisively address conflicts to prevent significant instability, such as a general strike or violence. However, there is a lack of leadership that truly comprehends and addresses the everyday suffering of the people, as well as a lack of innovative ideas for change.

Therapy: Ten possible solutions for SPA-M joint action and reconciliation, utilizing Maoists as a source of energy and national renewal for a better Nepal, with youth challenging them into action:

[a] Establish committees, like the National Monitoring Ceasefire Committee, to address major social issues at various levels, including villages, districts, regions, and the central government.

[b] Implement “positive disarmament” by drawing lessons from the Nicaraguan Sandinista-Contra teams of former militants and military personnel for joint reconstruction of destroyed infrastructures like bridges, clinics, and schools.

[c] Deploy teams of Maoists and others to remote villages to collaborate with the local population to enhance literacy in Nepalese, and other languages.

[d] Enforce quotas for women, youth, and dalits in political bodies at all levels, without waiting for the constitution to catch up.

[e] Ensure Nepal adopts is up-to-date, with labor-intensive, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly appropriate technologies.

[f] Experiment with labor value-based economic niches to alleviate poverty.

[g] Seek expertise from India on federalism to share with Nepalese experts, while adhering to panch shila principles of non-interference.

[h] Invite the USA to resolve conflicts like 9/11, as Spain did with “11M”, without intervening in Nepalese politics.

[i] Begin contemplating the components of a reconciliation process.

Conclusion: 11 mediated conflicts + 1 cease-fire = 12 tasks + conciliation = sustained perpetual peace.

Johan Galtung’s contributions to mediation simplified the work of conflict transformation in Nepal. His charismatic personality, dynamic leadership, deep knowledge of the world’s conflict resolution initiatives, and his experiences as a mediator all played a crucial role in finding a middle way for Nepal. Galtung’s visits to Nepal and his engagement with a wide range of leaders, international communities, and civil society created a conducive environment for the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord. Many of his recommendations made by him are included in the Constitution.

8. Freedom from Conclusion

In early July 2010, TRANSCEND International organized a week-long international meeting at Sydney University in Australia. Approximately sixty TRANSCEND Members from 36 countries, including Europe, America, Japan, South Korea, India, and Nepal, were in attendance. Among them was Professor Dr. Jorgen Johansen, one of 20 writers present, who had planned to publish a book titled, “Experiment with Peace: Celebrating Peace on Johan Galtung’s 80th Birthday”. However, in January 2010, Johnson sent an email informing us about the book. We had already agreed to support him by writing an article for the book he was editing, with the condition that the book would only be revealed during an event on Galtung’s birthday on October 24, 2010.

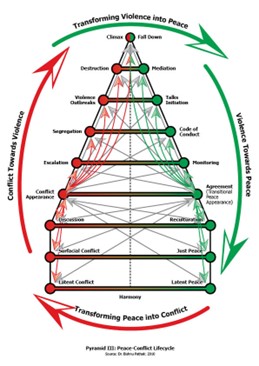

I also published “Approaches to Peacemaking”, three days before Galtung’s birthday. In my paper, Galtung’s different stages of conflict and peace cycle were presented in a unique way in a Pyramid. I was worried that Galtung might see my peace-conflict lifecycle and that our relationship would suffer. However, on his birthday, he came down from the stage and approached the participants to sign the books brought by readers. To my surprise, Galtung expressed his happiness while showing my peace-conflict cycle to them. Upon hearing this, I was not only impressed by seeing his greatness, generosity, and respect for his student’s innovation, but his behavior continues to influence me to this day.

Conflict arises in the complex human mind, eventually escalating to a violent climax after progressing through various stages: latent conflict, surface conflict, discussion, the appearance of conflict, escalation, outbreak of violence, segregation, and destruction.

The early stages of a dispute, when the potential for conflict exists but has not yet materialized, are known as latent conflict. Another name for it is the pre-conflict phase or hidden conflict. Conflict that is evident but has little or no underlying causes is referred to as surficial conflict. The term can also be used to describe a condition where different surfaces of a sheet develop or shrink at different rates. A conflict that can be settled amicably through negotiation might be referred to as a discussion. The appearance of a conflict is when a situation appears to potentially be a conflict of interest. When a disagreement or dispute intensifies over time and becomes increasingly aggressive, it is referred to as conflict escalation.

Segregation is used to describe a variety of conflicts that result from individuals being separated from one another based on factors like race, caste, community, gender, religion, location, hierarchy, and occupation. An outbreak of violence is the precursor of a conflict between nations or groups. A number of opposing circumstances, including political decisions, security force activities, legal reform or amendment, and state or party crimes, led to the unavoidable outcome of war. Destruction is a conflict where issues are left unresolved or transformed when one party dominates the other. The turning point of violence or conflict, when the opposing forces are at their highest point and the protagonist faces them, is known as the climax.

From the violent climax, the conflict transitions towards peace when one group triumphs over the other, there is a stalemate, or through pressure or force. The de-escalation phases may involve direct and indirect mediation (including facilitation, if necessary); formal or informal dialogue (initiation of talks) or negotiation; establishing a code of conduct for bargaining; a monitoring mechanism for signed understandings, agreements, and accords; and reculturation is achieved until conflict reappears.

The falling down violence is a crucial part of a story’s plot structure where the central conflict moves towards resolution or transformation into perpetual peace. Mediation is a neutral third-party involvement in a structured dialogue process that helps conflicting parties reach a mutually acceptable agreement. The ability to initiate a conversation and interact effectively with people is known as talks initiation, a vital social skill that fosters better relationships, empathy, communication, and conflict resolution abilities. A code of conduct is a set of guidelines outlining what to do and not to do during a ceasefire or temporary conflict settlement. Monitoring is the process of confirming and ensuring that the conditions of a ceasefire agreement or temporary conflict settlement are being followed.

An agreement is a formal pact that holds between two or more parties that ends violence or war. Reculturation is the process of reconnecting with families and societies in one’s birth culture, falling under the phase of rehabilitation, reintegration, reconstruction, restructuring, and reconciliation (5R). The concept of “just peace” is a method of achieving perpetual peace and justice through collaboration and nonviolent strategic means. Latent peace is a situation where differences of opinion exist, but are not yet enough to cause unrest, a form of negative peace, known as the latent peace stage or pre-conflict phase.

The latter refers to litigation, arbitration and adjudication aimed at promoting coexistence through truth, respect and tolerance in post-conflict society. In this manner, conflict tapers off, fades away, disappears, and peace is achieved until conflict reappears. Peace-conflict has its own lifecycle, much like an ecosystem (see above Pyramid). There are interrelated relationships at each phase of peace-conflict. For example, the conflict appearance phase may transition to peace through mediation, talks, code of conduct, monitoring, agreement, reculturation, and the reciprocal relation of the peace phase as well. This cycle repeats throughout the life-time of individuals and institutions. Any conflict has not been exempt from this cycle. The appearance, disappearance and reappearance of conflict-peace is known as the peace-conflict lifecycle similar to the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis (TATS) phases.

For Galtung, the Conflict Lifecycle is of utmost importance. He divides it into three phases: before violence, during violence, and after violence, focusing on attitude (hatred), behavior (violence) and contradiction (problem). He emphasizes that there is also a distinct Peace Lifecycle that runs parallel to the Conflict Lifecycle (Galtung, 2008).

At the age of 12, Galtung witnessed his father being arrested by the Nazis, which led to a deep aversion to conflict, violence, and the very word “war.” Additionally, he was imprisoned for six months alongside other criminals as he denied mandatory Norwegian military service in 1951 (Miall, March 25, 2024). This experience fueled his rebellion against violence and war.

His rebellion led him to dedicate his life to transforming conflict through peaceful means and achieving peace through non-violent methods. Today, despite the proliferation of peace studies, peace research, and related organizations worldwide, almost all of them trace their origins back to Galtung’s ideals. Central to his teachings is the concept of positive peace, which aims for lasting or perpetual peace.

Perpetual peace is not just a goal for today, but also for tomorrow. It does not dwell on the past or solely focus on the present but envisions a peaceful future for all. Perpetual peace is not just external; it is also an individual’s inner journey that involves seeking peace within oneself. As Galtung said, perpetual peace should be sought internally, through questioning and understanding our inner selves. Perpetual peace is a virtue that soothes the mind on an individual level, fosters mutual respect on an institutional level, promotes mutual benefit between societies, and advocates for mutual sovereignty and territorial integrity on a national level. It also encourages acceptance of mutual coexistence, non-interference, and non-aggression on an international level. Last, but not least, perpetual peace and Johan Galtung have become synonymous with each other. It is incomplete to discuss perpetual peace without mentioning Galtung. Similarly, Galtung is inseparable from the concept of perpetual peace. Perpetual peace and Galtung are two sides of the same coin.

References:

- Archibugi, Daniele. (1992). “Models of International Organization in Perpetual Peace Projects”. Review of International Studies. Volume 18. No. 4.

- Bastola, Susmita. (2023, January 31). Possibilities of Reconciliation: Studying Violence and Enforced Disappearances from the Post-Conflict Tharu Communities of Nepal. A Doctoral Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Osaka Jogakuin University.

- (2020, March 5). Ukraine- Profile Timeline. Retrieved November 26, 2024, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-18010123.

- Berger, Guy. (2009). Freedom of Expression, Access of Information, Empowerment of People. CSDRC. Retrieved November 25, 2024, from https://gsdrc.org/document-library/freedom-of-expression-access-to-information-and-empowerment-of-people/.

- Bilgin, K. (2018). Johan Galtung, Barış Çalışmaları. Ankara: Adres Yayınları.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu. (2005). In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon. Simon and Schuster.

- Brand-Jacobsen, Kai Frithjof. (2003, January 7). Peacebuilding and Conflict Transformation Nepal: Towards a Comprehensive Strategic Framework. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://web.archive.org/web/20060929061948/http://www.transcend.org/t_database/articles.php?ida=150.

- Browsing: Johan Galtung. Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://jfsdigital.org/category/authors/johan-galtung/.

- Buddha. Retrieved November 23, 2024, from https://www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/buddha/.

- Burak, Ercoskun. (2021, January). “On Galtung’s Approach to Peace Studies”. Lectio Socialis. Volume 5. Issue 1. DOI: 47478/lectio.792847.

- Burton, Candace W; Gilpin Claire E; and Moret, Jessica Draughon. (2021). Structural violence: A concept analysis to inform nursing science and practice. Wiley Periodicals LLC. DOI: 1111/nuf.12535.

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr. and Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Charles-Irénée Castel, abbé de Saint-Pierre. Retrieved November 19, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Irenee-Castel-abbe-de-Saint-Pierre.

- Chase, Tutor. (2024, September 9). Conflict Dynamics and Models. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 26, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/09/conflict-dynamics-and-models/.

- Chefalo, Shenandoah. (2023, March 24). What is structural violence? The National Prevention Science Coalition. Retrieved November 29, 2024, from https://www.pacesconnection.com/blog/what-is-structural-violence.

- Deudney, Daniel H. (2007). Bounding Power: Republican Security Theory from the Polis to the Global Village. Princeton University Press.

- Dijkeme, Claske & d’Hères, Saint Martin. (2007, May). Negative Versus Positive Peace. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-notions-186_en.html.

- Galeotti, Mark and Hook, Adam. (2019). Windrow, Martin (ed.). Armies of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Oxford New York: Osprey Publishing.

- Gallardo, Luis. (2024, February 26). In Memory of Johan Galtung: An Inspiration for Fundamental Peace and Happytalism. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 5, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/02/in-memory-of-johan-galtung-an-inspiration-for-fundamental-peace-and-happytalism/.

- Galtung Institute for Peace Theory and Peace Practice. Retrieved November 16, 2024, from https://www.galtung-institut.de/en/home/johan-galtung/.

- Galtung, Johan. (1969). “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research”. Journal of Peace Research. Volume 6. No. 3.

- Galtung, Johan. (1975, November 12-15). Interdisciplinary Expert Meeting on the Study of the Causes of Violence. Paris: United Nations, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Galtung, Johan. (1996). Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. London: Sage.

- Galtung, Johan. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization.International Peace Research Institute Oslo. Sage Publications.

- Galtung, Johan. (2000). Conflict Transformation by Peaceful Means. UN Disaster Management Training Program.

- Galtung, Johan. (2003, May 22). The Crisis in Nepal: Opportunity + Danger. Retrieved November 26, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/files/article525.html.

- Galtung, Johan. (2004). Transcend and Transform. London: Pluto; Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

- Galtung, Johan. (2008). 50 Years: 100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives. TRANSCEND University Press.

- Galtung, Johan. (2013, February 18). Nepal Six Years of “Transition”. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2013/02/nepal-six-years-of-transition/.

- Galtung, Johan. (2014, November 21). Public Lecture on Speaking Peace from Resolving Conflict between Buddhists and Muslims in Myanmar and Sri Lanka. IIUM Malaysia. Retrieved November 29, 2024, from https://iais.org.my/events/1233-public-lecture-seeking-peace-from-resolving-conflict-between-buddhists-and-muslims-in-myanmar-and-sri-lanka-by-prof-dr-johan-galtung.

- Galtung, Johan. (2024, August 24). Conflict Transformation by Peaceful Means. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 23, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/08/conflict-transformation-by-peaceful-means/.

- Galtung, Johan. (Undated). A Mini Theory of Peace. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.galtung-institut.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Mini-Theory-of-Peace.pdf.

- Gethin, Rupert M.L. (1998). Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press.

- Gleditsch, Nils Petter. (2024, February 17). Johan Galtung. Peace Research Institute Oslo. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.prio.org/news/3505.

- Global Governance Institute. (2024, February 19). In Memory Johan Galtung. Brussels. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.globalgovernance.eu/news/in-memoriam-johan-galtung.

- Government of India. (Undated). Legal Rights of Women. National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from https://www.minorityaffairs.gov.in/WriteReadData/RTF1984/5553835146.pdf.

- Grewal, Baljit. (July 29, 2024). Johan Galtung: Positive and Negative Peace. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/07/johan-galtung-positive-and-negative-peace/.

- Haavelsrud, Magnus; Vambheim, Vidar; and Balsvik, Randi Rønning. (2024, March 11). Remembering Johan Galtung. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 3, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/03/remembering-johan-galtung-24-oct-1930-17-feb-2024/.

- Hinton, Alexander (2022, February 25). “Putin’s claims that Ukraine is committing genocide are baseless, but not unprecedented”. The Conversation. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://theconversation.com/putins-claims-that-ukraine-is-committing-genocide-are-baseless-but-not-unprecedented-177511.

- How do you apply the conflict triangle model to peacebuilding interventions? Retrieved November 16, 2024, from https://www.linkedin.com/advice/1/how-do-you-apply-conflict-triangle-model-peacebuilding.

- Inayatullah, Sohail. (2024, February 26). Johan Galtung: Macrohisorian, Futurist, Peace Theorist. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/02/johan-galtung-macrohistorian-futurist-peace-theorist/.

- Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation. (1993). Professor Johan Galtung: Recipient of the International Award for Promoting Gandhian Values Outside India. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://www.jamnalalbajajawards.org/Media/pdf/JBA_1993_Bio_Johan_Galtung(1).pdf.

- Johan Galtung distinguished between positive and negative peace. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https://www.visionofhumanity.org/introducing-the-concept-of-peace/.

- Johansen, Jorgen and Jones, John Y. (2010). Experiment with Peace: Celebrating Peace on Johan Galtung’s 80th Birthday. Oslo: North-South. Available Online at http://www.transnational-perspectives.org/transnational/articles/article493.pdf.

- Kant, Immanuel. (1795). Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Essay. Translated by M. Campbell Smith. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

- Kraemer, Kelly Rae. (2024, March 25). Remembering a voice for peace: Johan Galtung (1930-2024). TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 1, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/03/remembering-a-voice-for-peace-johan-galtung-1930-2024/.

- Laumakis, Stephen J. (2023). An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, Bandy X. (2019, March 1). Structural Violence. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved November 29, 2024, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119240716.ch7.

- Lynch, Jake. (2024, July 29). Tribute to Johan Galtung (1930-2024): A Personal Recollection. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/07/tribute-to-johan-galtung-1930-2024/.

- Mehdi, Syed Sikandar. (2024, November 18). Henry Kissinger, Johan Galtung and the Nobel Peace Prize. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 25, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/11/henry-kissinger-johan-galtung-and-the-nobel-peace-prize/.

- Miall, Hugh. (2024, March 25). Johan Galtung Obituary. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 16, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/03/johan-galtung-obituary/.

- Monier-Williams, Monier.(1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press.

- Johan Galtung, Rector, Transcend University (Norway). Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/SForum/SForum2012/Biographies_27092012.pdf.

- Oneal, John R. and Russet, Bruce M. (1997). “The Classical Liberals Were Right: Democracy, Interdependence, and Conflict, 1950-1985”. International Studies Quarterly. Volume 41. Issue 41. Doi:1111/1468-2478.00042

- Pathak, Bishnu. (2013). “Concept and Major Initiatives of Human Security”. Contemporary Sociological Global Review. Volume 3. No. 3. Doi: 10.6040/s2027.7431.38118x.

- Pathak, Bishnu. (2013, February 11). Nepal’s First Peace Event 2013 with Professor Dr. Johan Galtung. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 25, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2013/02/nepals-first-peace-event-2013-with-prof-dr-johan-galtung/.

- Pathak, Bishnu. (2013, September 2013). “Origin and development of human security”. International Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Volume 1. No. 9.

- Pathak, Bishnu. (2014, March). “Human Security and Human Rights: Harmonious to Inharmonious Relations”. Archives of Business Research. Volume 2. No. 1. Doi:14738/abr.21.145.

- Pathak, Bishnu. (2016, August 29). Johan Galtung’s Conflict Transformation Theory for Peaceful Freedom: Top Ceiling and Traditional Peacemaking. Global Peace Science & TRANSCEND Media Service. New York: Global Harmony Association. Available Online at https://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=595 & https://www.transcend.org/tms/2016/08/johan-galtungs-conflict-transformation-theory-for-peaceful-world-top-and-ceiling-of-traditional-peacemaking/.

- People’s Review. (2003, May 22-28). Johan Galtung suggests for revision of constitution. Retrieved November 19, 2024, from https://groups.google.com/g/soc.culture.nepal/c/Q-p_32fsAd4?pli=1.

- Rakesh, Saksana. (2015). Buddhism and Its Message of Peace. Retrieved November 22, 2024, from https://www.ayk.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/SAKSANA-Rakesh-Buddhism-and-Its-Message-of-Peace.pdf.

- Right Livelihood Award. (2024, March 11). Johan Galtung, “the Father of Peace Studies,” Dies at 93. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 2, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/03/johan-galtung-the-father-of-peace-studies-dies-at-93/.

- Rosa, Antonio C.S. (2024, October 21). Johan Galtung: Father of Peace Studies (24 Oct 1930-17 Feb 2024). TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 24, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/10/prof-johan-galtung-father-of-peace-studies-24-oct-1930-17-feb-2024/.

- Russett, Bruce; Oneal, John R.; and Davis, David R. (1998). “The Third Leg of the Kantian Tripod for Peace: International Organizations and Militarized Disputes, 1950-85”. International Organization. Volume 52. Issue 3. Doi:1162/002081898550626

- Sandy, Leo R. (Undated). Johan Galtung. Plymouth State University.

- Scharmer, Pau. (2024, February 21). Johan Galtung: Peace with Peaceful Means. Retrieved November 21, 2024, from https://medium.com/presencing-institute-blog/johan-galtung-peace-with-peaceful-means-e0c184335c03.

- School of Public and International Affairs. (2015, November 17). Guest Speaker: Professor Johan Galtung. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https://spia.uga.edu/event/guest-speaker-professor-johan-galtung/.

- Semashko, Leo. (2024, November 19). “Comments on Perpetual Peace for the Russia-Ukraine War”. Featured Research Paper. TRANSCEND Media Service of November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/11/perpetual-peace-plan-for-the-russia-ukraine-war/

- Sharma, Narayan. (2024, November 8). “Comments on Perpetual Peace for the Russia-Ukraine War”. Featured Research Paper. TRANSCEND Media Service of November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/11/perpetual-peace-plan-for-the-russia-ukraine-war/

- Smith, Mary C. (2016). Perpetual Peace; A Philosophical Essay (Translation of Immanuel Kent’s original book). Translated by Project Gutenberg.

- Strong, J.S. (2001). The Buddha: A Beginner’s Guide.Oneworld Publications.

- Tanabe, Juichiro. (2016 Fall). “Buddhism and Peace Theory: Exploring a Buddhist Inner Peace”. International Journal of Peace Studies. Volume 21. No. 2.

- TRANSCEND Media Service. (2013, March 4). Interview with Johan Galtung on Nepal. Retrieved November 23, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2013/03/interview-with-johan-galtung/.

- TRANSCEND Peace University. Retrieved November 18, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tpu/.

- Urban, Susanne. (2024, August 5). Invitation to the Memorial Gathering for Kohan Vincent Galtung in Hardangar, Norway. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved November 21, 2024, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/08/invitation-to-the-memorial-gathering-for-johan-vincent-galtung-in-hardanger-norway/.

- Vision of Humanity. (Undated). Johan Galtung, 1930-2024: A Life Dedicated to Peace. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.visionofhumanity.org/johan-galtung-1930-2024/.

- Vorobej, Mark. (2008). “Structural Violence”. The Canadian Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies. Volume 40. No. 2.

- What’s the difference between Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana ? (Undated). Tricycle Buddhism for Beginners. Retrieved November 16, 2024, from https://tricycle.org/beginners/buddhism/whats-the-difference-between-theravada-mahayana-and-vajrayana/.

- Wilson, Jeff. (2010). “Saṃsāra and Rebirth”. Buddhism. Oxford University Press.