Unfortunately, in both cases, these assumptions are false. Those who make them about Hamas choose to highlight the statements contained in their constitution in which they express their intention to eradicate Israel. They ignore Hamas’s subsequent political statements in which the organization states its readiness to accept UN resolutions as well as those of the Security Council, even though these only provide 22% of the territory of Palestine for the Palestinians.

To defend an equally dubious interpretation in the case of Russia, one must stick to a few lines of Vladimir Putin’s text from July 2021 or certain sentences spoken on the eve of the special military operation. On both occasions, Putin refers to the fact that there are no significant differences of identity between Ukrainians and Russians, that Ukraine has for a long time been part of historical Russia, and that the borders separating them are only administrative and therefore somewhat arbitrary. These statements would serve the cause of his imperialist ambitions of territorial conquest. Some see in them the influence of the philosopher Alexander Dugin, whom Putin has practically never read or met. The American philosopher Jason Stanley also explains the invasion of Ukraine by relying on Putin’s few identity-related remarks and, in his book Erasing History, he describes the popular support enjoyed by the Kremlin leader by the fact that his theses concerning historical Ukraine are taught in schools. These theses would have served as an alibi for an invasion motivated by ambitions of territorial conquest. Stanley claims that education has consolidated the regime by reshaping the understanding of the past. For others still, it is the undemocratic character of the regime that would explain the brutality of the undemocratic solution adopted. In any case, all these claims suggest that the invasion of Ukraine proceeds from factors internal to Russia and that it must be morally condemned.

Those who are obsessed with attributing imperialist ambitions to Putin ignore the fact that his intervention in July 2021 and the one made just a few days before, on February 24, 2022, were simultaneously accompanied by the recognition of Ukraine’s sovereignty. Putin’s remarks on this subject have unfortunately simply been ignored or glossed over. However, they make problematic an interpretation of the invasion based on imperialist conquest objectives. Those who propagate these ideas especially ignore the repeated warnings coming from the Kremlin not to include Ukraine in NATO. They forget Moscow’s support for the Minsk agreements. They ignore Russia’s proposals of December 2021 concerning security in Europe. They omit the agreement that Russia and Ukraine concluded in April 2022. However, these repeated actions reveal Moscow’s real preoccupation and they clearly concern security.

Russia had no imperialist ambitions in launching its special military operation in Ukraine. In order to ensure its security on the border, Moscow believed that it had to demilitarize a Ukrainian army trained, equipped, and fortified by the West and that it had to denazify the regime under the control of a minority of extremists fueled by hatred of Russia and the Russian-speaking people of Donbass. These two specific goals, according to the Russians, would increase security and defuse the instrumentalization of Ukraine that the United States was trying to implement in order to weaken Russia. Instead of referring to explanations based on the ideas of Dugin or Stanley, we recommend those of Scott Horton who, in his book Provoked, provides, in our opinion, a better understanding of what happened.

The above remarks should have been enough to convince everyone that the special military operation had nothing to do with territorial ambitions. Nor does it have anything to do with the “authoritarian democracy” that characterizes Russia’s internal political regime, because it is explained by considerations related to geopolitics. The fixation on the idea of “unprovoked aggression,” or aggression that must be “morally condemned,” may have a “salutary” effect on some minds, but it only reinforces deeply rooted Russophobic prejudices.

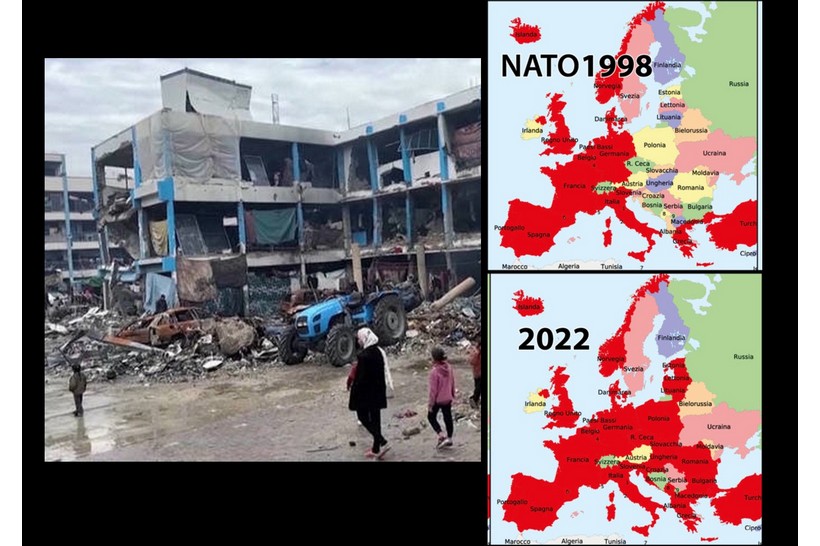

Even if Russia’s internal regime is perhaps not recommendable, this has nothing to do with its foreign policy. From a geopolitical perspective, we should rather focus on the imperialist character of the US foreign policy. This country uses NATO to establish its economic hegemony by force, at the expense of the Ukrainian people and European countries. In the minds of American leaders, the US was only responding favorably to the requests for protection coming from the former Eastern European countries. But in fact, the US’s favorable response was based on an ambition to spread throughout the world the “values” that it believed it had already established at home.

Being forced to intervene

From the US perspective, provoking Russian intervention on Ukrainian territory was important because it would finally allow it to justify “sanctions” against Russia: in particular, ending the sale of Russian gas and oil to Europe and ending the Nordstream project, goals that Washington had been entertaining for years. It was therefore necessary to compromise Russia so that it get bogged down in a long-term war in Ukraine.

Russia was certainly not naive about these provocations, but at the same time, it had to face the facts. Ukraine had become a de facto member of NATO. The Minsk agreements had still not been implemented. These so-called “agreements” had only given the Ukrainian army time to equip itself and train under the guidance of certain NATO countries. Territorial fortifications had been created all over the territory. What is more, Washington had rejected Russia’s proposals of December 2021 regarding European security.

Then, according to Ray McGovern, even if Biden had promised on December 31, 2021 not to install nuclear missiles on Ukrainian territory, a few weeks later, this promise was already off the table. If the Americans installed anti-ballistic missile systems in Poland and Romania after withdrawing from the ABM treaty in 2002, they would probably be able and willing to install medium-range missiles in Ukraine, after withdrawing from the IMF treaty in 2019.

Finally, tensions were rising in Donbass, with the Ukrainian army increasingly concentrated in the region. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) noted a significant increase in armed incidents and explosions occurring in both republics.

Russia felt it had no choice but to engage in what it called a “special military operation.” Nothing short of military intervention would prevent the United States from constantly provoking Russia by creating conditions for escalating tensions. Those who believe it had a choice must point out what other avenues remain to be explored. Above all, they must show that these “solutions” would not have led the United States to find other ways to provoke escalation.

Simply establishing a causal link between the events that took place does not mean that the interventions were not planned. The special military operation was, of course, planned. Russian troops had been stationed along the Ukrainian border for several months. To say that American provocations caused the special military operation simply means that the intervention had become unavoidable. The Russian authorities considered that there were no other options left for Russia to explore. More precisely, Putin understood that any other option would only lead to new provocations. This reaction is, in its inevitability, to a certain extent comparable to that of Hamas, even if, in the latter case, one must mention the desperate situation in which this people, forgotten by the international community, found themselves.

To say that war was inevitable does not mean that it was morally justified. It means that perhaps we should not condemn it either. Similarly, in the Middle East, the Abraham Accords could be signed without taking into account the Palestinian people. It was necessary to act quickly so that the whole world would remember the Palestinian cause.

We were now far from the famous “unipolar moment” and the American desire to “generously” propagate Western “values” outside its borders. Since at least 2014, and even more so since 2019, based on the Rand Corporation document “Extending Russia,” a growing concern animated the White House. The Americans feared losing their hegemony. It was necessary to act quickly to weaken Russia.

International law

Shouldn’t we nevertheless condemn the Russian aggression? In international law, the issue is very complex. A country has the right to intervene in another country if it so requests. The self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Luhansk requested Russia’s intervention. A few days before the invasion, Putin recognized these two oblasts as sovereign states precisely for this reason. His intervention in Donbass was therefore technically legal.

But did he have the right to intervene elsewhere in Ukraine? From Putin’s point of view, it was necessary to put an end to an escalation that was about to lead to the installation of nuclear missiles on Russia’s borders. A preventive military intervention is, however, only legal if one obtains the approval of the Security Council. But there was no question of being able to get it, since the United States has veto. It was therefore an illegal intervention. But was it legitimate? Can Russia plead its case and invoke the legitimacy of its approach? Must positive law be transformed to take this reality into account?

One can refuse to legitimize it while still claiming that it was inevitable. This is the position that John Mearsheimer, Ray McGovern, and Norman Finkelstein seem to take. It is similar to Finkelstein’s attitude toward October 7, 2023. There is no possible moral justification for the horror that took place on October 7, 2023. The Palestinians in Gaza were certainly acting in self-defense against the occupying foreign power, but that does not morally justify the actions taken during the uprising. A similar observation applies to the war in Ukraine. Russia, for its part, was not acting in self-defense. It did have legitimate security interests, but that does not morally justify the violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. So there seem to have been war crimes committed in both cases: the massacre of civilians by Hamas and the violation by Russia of Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

Should we then condemn them? Should we not rather seek to understand the causes without passing judgment? Perhaps this is the perspective we should adopt.

Conclusion

The events of February 24, 2022, and those of October 7, 2023, both illustrate extreme recourses to violence. Nevertheless, the condemnation of the Hamas insurgency and the Russian special military operation may be unfounded. The war crimes committed should certainly not be condoned, but it is wrong to interpret them in terms of objectives that are unrelated to what these two peoples have had to endure. The invasion of Ukraine was not based on territorial conquest objectives and the invasion of Israel by Hamas was not explained by the desire to eradicate the Israeli people.

On October 7, 2023, the Palestinian people sought to defend themselves against Israel’s illegal occupation of their territory, while on February 24, 2022, Russia sought to ensure their security at the border. In both cases, the motives were valid even if the actions taken cannot be morally justified.

In both cases, the actions violated international law: attacking civilian populations for Hamas, and violating the territorial integrity of Ukraine for Russia. In an ideal world, such events should never take place. But we are not in an ideal world. While one might hope that international law would serve to establish a set of standards that must always be respected, violence sometimes inevitably leads to violence.

To break out of the cycle of violence, we need to be able to correctly identify what is at stake. In both cases, we may need to turn to the United States, for whom Israel is a kind of protectorate and Ukraine a kind of proxy.

_______________________________________

Michel Seymour is a retired professor in the Department of Philosophy at the Université de Montréal, where he taught from 1990 to 2019. He is the author of a dozen monographs, including A Liberal Theory of Collective Rights, 2017; La nation pluraliste, co-authored with Jérôme Gosselin-Tapp, for which the authors won the Canadian Philosophical Association Prize; De la tolérance à la reconnaissance, 2008, for which he won the Jean-Charles Falardeau Prize of the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences. He also won the Richard Arès prize from Action nationale magazine for Le pari de la démesure, published in 2001. Email : seymour@videotron.ca web site: michelseymour.org

Michel Seymour is a retired professor in the Department of Philosophy at the Université de Montréal, where he taught from 1990 to 2019. He is the author of a dozen monographs, including A Liberal Theory of Collective Rights, 2017; La nation pluraliste, co-authored with Jérôme Gosselin-Tapp, for which the authors won the Canadian Philosophical Association Prize; De la tolérance à la reconnaissance, 2008, for which he won the Jean-Charles Falardeau Prize of the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences. He also won the Richard Arès prize from Action nationale magazine for Le pari de la démesure, published in 2001. Email : seymour@videotron.ca web site: michelseymour.org