Before, With and After Johan Galtung

PAPER OF THE WEEK, 27 Jan 2025

Prof. Tiziano Telleschi - TRANSCEND Media Service

An (almost) Case Study: Symbolic Violence at the Restaurant

21 Jan 2025 – Think about what can happen at a formal dinner at a restaurant to draw the necessary lessons from it. The scene takes place in Italy, where the meal is not simply nourishment and where gathering at the family table is a living tradition which rooted in deep culture. The parents of my grandchildren, five-year-old Olga and eight-year-old Edward, need to be reminded often enough that one does not put one’s hands on the plate or elbows on the table, that the knife is not for stabbing food but for cutting it. As for most parents, more or less consciously, “dining etiquette” are among the marks of recognition of a certain social prestige. Their hope is that in a few years’ time the two children will be able to devote their full attention to the proper way of holding a fork and knife, sitting at the table with an erect torso and participating in conversation with other table-companions.

This ritual, like all the countless others to which they will be called throughout their lives, serves a very important purpose. It provides access for living, communicating and interacting in a social context without having to invent the “right” key each time through trial and error, so it becomes a mental scheme that doesn’t need active reasoning anymore. That is to say, each context, though initially indecipherable, is not chaotic nor does it face random behaviors, but is structured according to practical, countless and almost never explicit “rules” underlying rituals, pre-created for thinking about the external world and ourselves, ‘to whom’, ‘how’, ‘where’ and ‘when’ to communicate and express ourselves.

Rituals define what in a specific context originates and what is “important” (people, words, objects, events, actions). By learning the “rules” of how a given context works (from home to school, work, religious, politics, leisure one, etc.) we learn the intuitive sense of what is correct or incorrect, repeatable or non-repeatable, good or not good relating to emotions, beliefs, moral sense as well as stereotypes and hierarchical classifications. Here, by performing that “ruled” ritual, my grandchildren will have learned beyond the careful thought (Bateson, 1977 [1972]) some habits of acting in a unreflective and at the same time controlled and organized manner in a specific context, the restaurant; a context that requires practical skills appropriate to the expectations of the table-companions. By the very fact of conforming to these expectations, the two children will reproduce them, albeit interpreted with some personal nuances, and in doing so will likely contribute to the blame for all the dissimilar conduct they will have occasion to witness in similar contexts (from the school cafeteria, the parish dining hall to the party with friends in sports).

If, on the other hand, they eat noisily with their mouths open or put their hands in their plates to take their food or play from under the table, then it is very likely that disapproving looks and expressions of disappointment, that is morally sanctioning reactions, will come from the other tables, because those conducts “clash” with the place and discredit those sought-after customers who frequent it precisely to draw prestige from its registered trademark. Verisimilarly, the maître de salon would intervene with authority to restore the disrupted order by calling the two children back to more consonant behavior (moved also by the concern of “what will be the customer’s online review?”).

It is conceivable, however, that my grandchildren would not be capable of that “vulgar” conduct due to the fact that habits embedded in the course of socialization and structured into affective-cognitive and logical-practical patterns, together with the normative constraints and formal injunctions inscribed in the particular social environment, would create in their eyes strong evaluations “to be and maintain a certain evaluation” as who knows how to behave in a given situation. So much so that it raises in them emotions of embarrassment and shame of “losing face” so strong that they form an (almost) insurmountable barrier to conduct differently from that which “is suitable” in such contexts. By defending their “face,” they will implicitly defend their parents who have passed those rituals on to them (the “good table manners” as well as other minuscule yet endless social rituals).

At the same time they defend the society that instituted those rituals along with the power the society has to give legitimacy to “what’s worth, is important”. As a result, kids — and by extension parents — will be recognized as having a legitimate baggage of characteristics and properties (“marks of distinction”) in common with their social context of reference and with society as a whole: “good manners” or any proper “social game” implies a consensus to the social order that my grandchildren, like each of us, cannot fail to give in order to think of themselves as and be part of a social system and to do it in an almost automatic way.

It should be added that not all habits are impactful; some remain on the periphery of being as mere routines, but others hold authentic meaning for the subject who, insofar as he or she “cares about it,” are inscribed in the body (embodied cognition, as neuroscience notes) and preserved as the fundamental core of the habitus. Habitus constitutes the construct that organizes habits with associated cognitive-evaluative patterns and pre-orients the subjectively peculiar way of establishing any relationship with the world, communicating, loving, cooperating, making decisions.

The laboratory experiment of formal dining at a restaurant invites discussion of some weighty dimensions of the social world learning process. The first concerns the “ordered” character of the experience of reality for the explanation of which we must rely, with greater rigor than in the reported episode, on the refined techniques of ethnomethodological research (Garfinkel, 1967). Another concerns the relationship between the specific situation and society. If the acquisition of a ritual of social space consists of incorporating the principles that organize individual behavior, these organizing principles are not only incorporated and reproduced by individuals in the form of habitus, but are also objectified by the more or less formal institutions and beliefs of the social world.

A further point refers to the placement of the subject in the sphere of power. Social rituals are not neutral or flat, but rather asymmetrical, depending on the position and habitus that the subject holds within the geography of social space (by class, culture, education, religion, ethnicity, skin color etc.). Social space has always been crossed by logics that decide the dimensions of value and legitimacy of actions, positions, objects and individuals located in it; it is structured by a series of value oppositions that function as a matrix of competition and conflict between the habitus and the position each subject holds within it.

In such oppositions between what is refined and what is vulgar, polished and trivial, good and bad, spiritual and material, are already contained the positive or negative appreciations toward people, things and events so that each subject is placed on one side or the other of these oppositions, inside or outside a social sphere or at the margin.

It means that the regulatory principles of action that the subject incorporates through the social rituals structured in habitus, he incorporates them from a certain position within the social space, that social space to which are linked on the one hand the material and immaterial resources he has and on the other hand linked to the value of these resources with respect to the actual evaluation criteria, or at least those that count in his own strategy of accumulating recognition and prestige: Power to define the criteria that fix “what counts” is the stake in the exercise of social rituals, a social stake that can be described in different concepts, but always involves a form of dissymmetrical power relation. The struggle for recognition, as Bourdieu points out, place the dominated and the dominant in a competition concerning the legitimacy that one and the other have in defining the principle of distinction (which attach value to “whom” and “what”).

Competition in the distribution of power is already inherent in that hierarchy that distinguishes those who can legitimately afford to establish such criteria from those who are precluded from doing so. In turn, dissymmetry helps reproduce the order that makes those criteria and related inequalities exist. Power that succeeds in imposing differentiated value criteria and imposing them as legitimate by disguising the real imbalance on which it bases the relationship (Popitz, 1990 [1986]), so adds to the rituals it produces, and to the social action that follows, a specifically symbolic plus, that is, arbitrary, assumed outside consciousness and not negotiated, achieving to disguise such imposition as natural: here it’s hidden the form of violence that at different times Bourdieu and Passeron (1972 [1970] and Galtung (1990) have called symbolic violence.

Symbolic violence is not referable to specific agents, is as invisible as insidious, influences people in such a way that their physical and mental development is below their real potential, and consequently generates unequal life chances (please note, together with Soshuana Zubof, to the high impact of the surveillance’s power of the algorithm in the future of humanity in shaping the behavior of people and society, a totally self-authorizing power that has no basis in democratic or moral legitimacy.)

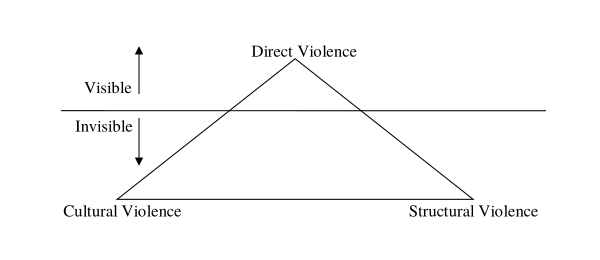

Symbolic violence manifests itself in every aspect of life, both in face-to-face relations (direct violence) and in indirect relations with institutions and external reality (structural violence). The three types of violence are interdependent. Each type of violence can transfer and influence the other types of violence. For example, if structural violence becomes institutionalized and cultural violence increases, then there is a strong likelihood that direct violence will increase. To limit or prevent one type from emerging, one must also deal with the other two and address them with concrete actions.

Herein lies the goal of the laboratory experiment of the formal dinner at the restaurant; it invites us to search for the mechanisms and steps through which symbolic violence in a given context is formed and legitimizes direct violence and structural violence. Which is what theoretical pluralism teaches us: we must learn to recognize, in a “regulated” context hooked on deep culture, the distribution of the principle of distinction, to identify the presence or predominance of one or the other form of violence and especially the ways of their conjunction or transition from one to the other.

This is an ambitious program to carry out which we should make the studies on the topic and equip ourselves with a set of concepts to describe the forces that move the social order and possible dysfunctions i.e., equip ourselves with a theory of power (including consensus) and a theory of social order (including social control).

References:

Bateson, G. (1972). Planning and the Concept of Deutero-Learning. Part. III, Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Chandler

Bourdieu, P. & Passeron, J-C. (1990 [1970]). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Sage Ltd

Galtung, J. (1990). Cultural violence, Journal of Peace Research, 3 (27), pp. 291-315.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall

Popitz, F. (2017 [1986]). Phenomenology of Power. Authority, Domination and Violence, trans. by G. Poggi. Columbia University

_________________________________________________________________

Tiziano Telleschi: Former professor of anthropology and sociology; senior fellow CISP-Interdisciplinary Center “Sciences for Peace,” University of Pisa; Network of Italian Universities for Peace (RUniPace).

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Conflict studies, Cultural violence, Direct violence, Johan Galtung, Peace Research, Peacebuilding, Structural violence

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 27 Jan 2025.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Before, With and After Johan Galtung, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.