Magna Carta of Peace

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 24 Mar 2025

Bishnu Pathak – TRANSCEND Media Service

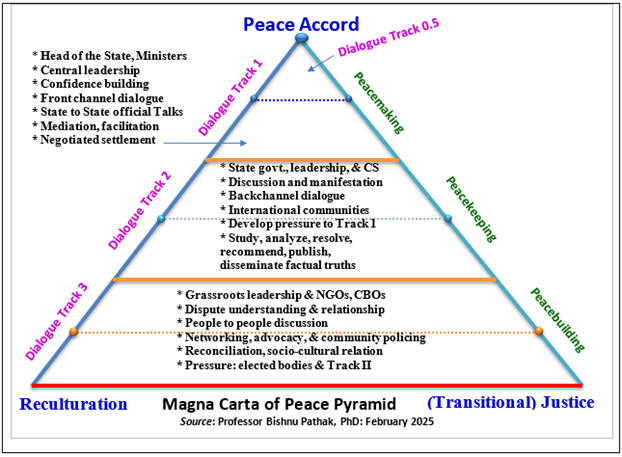

21 Mar 2025 – The Magna Carta, also known as the Great Charter, was established in 1215 as a historic legal document in England. In contrast, the Magna Carta of Peace (MCP) is nothing more than a Peace Accord. The MCP symbolizes unity, cooperation, collaboration, and harmony in society promoting reculturation and transitional justice. It upholds freedoms guaranteed by legal frameworks, including peace agreements, domestic constitution and laws, international human rights standards, international humanitarian law, international human rights law, and international criminal law. The pyramid structure of the MCP represents strength through unity (coming together) and collective (working together) effort.

The MCP is a civilian peace treaty without binding legal obligations serving as a guide for nations recovering from armed conflict, violence, and war. It consists of two stages: ex-ante and ex-post peace, promoting collaboration between leaders and people. The Peace Accord, Transitional Justice, and Reculturation outlined in the pyramid, are key components for diplomacy, conflict resolution, and transformation towards a more peaceful, hopeful, prosperous, and re-cultured society. This process aims to create a harmonious as well as prosperous society for all after signing of a peace accord.

When looking at global armed conflicts or violence, it is evident that those at the grassroots level are the most victimized, oppressed, marginalized, and vulnerable. This study seeks to empower these individuals through a bottom-up approach. The short paper “Magna Carta of Peace” is based on personal experiences, passion, and participant observation collected over four decades, rather than relying solely on theoretical concepts.

Reculturation and transitional justice are essential components in the process of resolving conflicts and transitioning towards peace following the signing of a Peace Accord. The study starts at the grassroots level in Dialogue Track 3, involving project preparation, initiation, formulation, planning, development, conflict transformation, and management (Simplilearn, November 20, 2024). This bottom-up approach aims to gain a deep understanding of the needs of the people involved (Main, November 30, 2023). Typically, this grassroots study begins with peacebuilding, peacekeeping, and peacemaking in dialogue tracks 3, 2, and 1, respectively. The concept of post-peacebuilding, introduced by United Nations Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali emphasizes preventive measures such as diplomacy, peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding in the peace accord agenda (Reychler, December 2017).

Peacebuilding is a new approach that aims to transition from conflict to peace by restoring a culture of justice and promoting peace and stability. It involves the participation of representatives from all parties, civil society, and elected local bodies in activities related to truth-seeking and sharing. During times of conflict, peacebuilding requires humanitarian aid to address basic needs at the grassroots level, known as Track 3, as an immediate response.

Peacebuilding is an ongoing process that operates both before conflicts arise and during times of conflict. It seeks to transform cultural and structural violence into positive personal, group, and political relationships across various boundaries such as class, caste/ethnicity, profession, race, geography, and religion. Peacebuilding is guided by principles of violence prevention, conflict management, resolution, transformation, and reculturation (Rapport, 1998 & 1992).

Peacebuilding is especially important for grassroots communities (Dialogue Track 3) compared to other Dialogue Tracks (2 and 1). At the grassroots level, peacebuilding involves community-led initiatives to address violence, promote reconciliation, and apply humanitarian emergencies among communities who are most vulnerable in armed conflicts. When grassroots communities unite to address violence and promote reconciliation, their efforts can have a positive impact, influencing higher levels of Dialogue (Track 2 and 1) and even reaching the international community.

Peacebuilding at the grassroots level plays a crucial role in preventing future conflicts by facilitating communication between disputants and building relationships through various forms of dialogue tracking, including indirect and direct, as well as informal and formal methods[1]. Ultimately, these efforts are essential for promoting peace, progress, harmony, co-existence, and stability at all levels.

The United Nations’ peacekeeping efforts aim to promote, maintain, and restore international peace and security with the motto “live and let live peacefully”. This initiative began in Lebanon in 1958. The Magna Carta of Peace utilizes the Unarmed Civilian Protection Force (UCPF) where trained, unarmed civilians directly protect other civilians in situations of violence, focusing on community-led safety and security initiatives. The UCPF utilizes civilian-to-civilian interactions and civilian self-defense tactics to protect civilians in conflict zones, as outlined in Dialogue Track 2. This non-military strategy aims to reduce violence and damage in conflict zones, ultimately supporting peacebuilding efforts in Track 3 and Track 2 as a whole.

Peacekeeping involves the creation of a peacekeeping team that uses non-violent methods to protect people in grassroots and semi-urban areas, building connections within local communities and society. The main goal of the peace team is to bridge the gap between warring parties and innocent civilians. The team addresses the issues of warring parties by facilitating mediation and nurturing relationships.

Dialogue Track 2 refers to conflict resolution or transformation initiatives that are typically carried out by practitioners and theorists (Davidson & Montville, 1981-1982). State government leadership, including provincial government, legislative, judiciary, diplomatic, international agency officials, civil society representatives, and mid-level leadership of political parties, are usually involved in Track 2. Indirect and informal discussions and interactions among stakeholders typically take place through backchannel dialogue (Heinz, 2002). Backchannel dialogue progresses as unarmed peacekeepers report, facilitate, and monitor dialogue, while officials, especially those in Track 1, must apply pressure and offer moral support globally for this dialogue. Peacekeeping is an unarmed process that falls between peacemaking (Track 1) and peacebuilding (Track 3).

Peacemaking is a method employed to settle conflicts or violence by achieving a peace agreement known as a peace accord through negotiated settlement. It utilizes a range of front-channel approaches like dialogue, mediation, arbitration, adjudication, and negotiation to resolve conflicts and mend relationships across all levels. Peacemaking also deals with disputes within families, communities, workplaces, and regions. Track 1 dialogue, also referred to as “peacemaking through dialogue diplomacy” (McDonald, 2012), is a key component of this process.

Track 1 plays a central role in influencing discussions and their outcomes (Sanders, 1991) and works in conjunction with Track 2 (Montville, 1991). In Track 1.5, a third party mediates or facilitates interactions between the official representatives of the disputants in Tracks 1 and 1.5. Track 1 serves as a policy-making body that establishes a formal state-level dialogue team. This team is responsible for brokering peace talks, negotiating, and signing Peace Accords. By bringing together hostile groups or disputants to a roundtable for further discussion, the team aims to reach a peace accord that restores peace, truth, justice, harmony, and reculturation. Peacemaking also involves reconciling disputants when necessary, which is a part of restorative justice and includes non-restrictive, political, diplomatic, and judicial measures.

Confidence-building strategies can be strengthened through a mix of indirect and direct sharing, as well as snowball tactics. In Track 1, formal and direct communication, also known as front-channel communication, is used to kickstart a dialogue between two parties. A mediator or facilitator oversees this communication, following formal diplomatic procedures to work towards a peace accord. Track 1 involves official representatives like heads of state, ministries, and senior government officials. The peace agreement is signed by the Head of Government or their representative and the Head of the Conflicting Party or their representative in Dialogue Track 0.5. Track 1 transfers its discussions, decisions, and peace accord results to Track 2, and Track 2 communicates with Track 3.

After a peace accord is signed, reculturation is the first step to normalize the challenging post-conflict situation. This process primarily takes place in Track 3, Track 2, and Track 1, respectively. Reculturation involves reconnecting conflict victims to civilian life, including their family, birth culture, and society in a post-conflict setting to promote peace, harmony, and tranquility. It consists of several stages: Disarmament (D), Demobilization (D), Reinsertion (R), Repatriation (R), Resettlement (R), Rehabilitation (R), Reconciliation (R), and Reintegration (R), also known as 2D6R. The focus is on rebuilding positive relationships for lasting peace among individuals, groups, and societies.

Disarmament is the process of collecting, recording, managing, and disposing of arms, explosives, and ammunition used by combatants. It involves weapons surveys, collection, storage, destruction, and redistribution. It is the first step of the 2D6R process, generally led by a neutral third party, such as the United Nations or the European Union. Similarly, demobilization is the second step of the formal and controlled discharge of active combatants who were being kept in temporary cantonments-and-satellite cantonment (Caramés, et al., 2008). It involves a process of counseling, vocational training, and economic assistance.

Reinsertion is a short-term stabilization process that aims to transition former combatants away from armed conflict, civil war, or criminal activities until a peace and political mission can be implemented. It offers temporary income-generating opportunities to all former combatants, their dependents, and victims of conflict to assist with their immediate resettlement by addressing essential needs like food, shelter, clothing, healthcare, and education.

Repatriation allows individuals or groups to return to their country of birth or origin after being released from captivity or a foreign land. The 1949 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War mandates that prisoners of war must be granted the right to return to their homeland.

Resettlement is the act of moving individuals affected by conflict to a secure location where they can begin afresh. This could mean relocating to a new country or region, as is the case for internally displaced persons, immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees, and ensuring housing for vulnerable populations such as women, children, and the elderly.

Reintegration is a comprehensive process that helps individuals impacted by conflict or transitioning from military to civilian life reconnect with their families and communities. It addresses social, cultural, economic, legal, and psychological aspects to rebuild their security, dignity, and sense of belonging within their communities.

Reconciliation is the process of settling disputes and ending conflicts between two parties. Galtung introduced 12 approaches to reconciliation, such as reparation, apology, forgiveness, judicial punishment, karma, truth commissions, and joint sorrow. It is a complex term aimed at maintaining social harmony and justice among survivors’ families, relatives, and accused persons affected by armed conflict (Bloomfield, 2006).

The final component of the Magna Carta of Peace pyramid is Justice, which focuses on providing justice to the victims of conflict through transitional justice. Transitional justice aims to address past atrocities by bridging the gap between old and new regimes during democratic transitions. The Transitional Justice (Part 57): Six-Pillar of Transitional Justice has departed from the traditional four-pillar transitional justice model, rationalizing the confluence of six pillars: truth-telling, vetting, reparation, prosecution, guarantee of non-recurrence, and justice policies (Pathak, April 22, 2024).

Truth-telling is the process of involving victims, such as survivors, complainants, and witnesses, sharing historical truths to identify and evaluate testimonies and information. Testimonies are typically collected through participant observation. When collecting information about victims of conflict, it is essential to ask questions about who, why, how, by whom, from where, and when their rights were violated. Accused individuals (perpetrators) also have rights, including access to information filed against them, the opportunity to present their side of the story, the right to an effective investigation, and the right to defend their innocence.

Vetting is the process of investigating and evaluating someone’s background to conduct checks on an individual’s past performances before making decisions related to hiring, promotion, and transfers. It is a process used by both employees and employers to identify, manage, and mitigate security risks.

Reparation is a form of compensation provided by the state to address victims’ psychological, material, physical, and emotional harms, including livelihood support such as cash and kind assistance. It encompasses relief compensation, restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and memorialization.

Prosecution aims to prevent individuals from engaging in unlawful retaliation and uphold the rule of law. It is a direct way of holding accountable those responsible for the crimes they have committed in the past.

Non-recurrence focuses on institutional reforms that ensure guarantees of non-repetition at the state, semi-public institutions, and societal levels. Justice is characterized by truthful, fair, impartial, and just behavior. It guides distributive, retributive, and restorative justice efforts in transitional justice.

Reculturation and transitional justice take place after conflicts, with the goal of achieving peace. They focus on creating a new peace accord based on civil law, ensuring justice for victims, holding perpetrators accountable or responsible, and upholding international human rights standards. In this context, victims and perpetrators are two sides of the same coin. A genuine peace accord (treaty) embodies justice, righteousness, legality, freedom, fairness, impartiality, non-hierarchy, and equity.

The following poetry can be used to explore different aspects of peace.

Peace is a universal concept that transcends all distinctions, such as caste and ethnicity.

Peace is unconcerned with skin color, social class, status, or rank.

Peace is above any occupation, position, or person.

Peace takes precedence over family, friendships, and personal connections.

Peace goes further than being a good neighbor.

Peace transcends nationality, religion, and cultural differences.

Peace breaks through language barriers, gender disparities, and class hierarchies.

Peace surpasses boundaries, politics, ideology, and opinions.

Peace is impartial, unbiased, fair, and just.

Peace values, protects, nurtures, and respects all lives.

Peace is a universal truth that applies to everyone.

Peace is a fundamental principle that goes beyond any Great Charter.

References:

Pathak, Bishnu. (2024, April 22). “Transitional Justice (Part 57): Six Pillar of Transitional Justice”. TRANSCEND Media Service. Available Online at https://www.transcend.org/tms/2024/04/transitional-justice-part-57-six-pillar-of-transitional-justice/.

Bloomfield, David. (2006). On Good Terms: Clarifying Reconciliation. Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management.

Caramés, A.; Fisas, V. Fisas; and Sanz, E. (2008). Liberia. Analysis of Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration Programs in the World during 2007. Escola Pau, Bellaterra.

Davidson, W. D., and Montville, J. V. (1981-1982). “Foreign Policy According to Freud,” Foreign Policy. Vol. 45.

Galtung, Johan. (2000). Conflict Transformation by Peaceful Means. UN Disaster Management Training Program.

Heinz, Bettina. (2002). “Backchannel responses as strategic responses in bilingual speakers’ conversations”. Journal of Pragmatics. Volume 35. Issue 7. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00190-X.

Main, Paul. (2025, January 25, 2025). Top-Down Processing And Bottom-Up Processing. Structural Learning. Retrieved January 25, 2025, from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/top-down-processing-and-bottom-up-processing.

McDonald, John W. (2012). “The Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy”. Journal of Conflictology. Volume 3. Issue 2.

Montville, J. (1991). “Track Two Diplomacy: The Arrow and the Olive Branch: A case for Track Two Diplomacy”. The Psychodynamics of International Relations. Volume 2.

Reychler, Luc. (2017, December). “Peacemaking, Peacekeeping, and Peacebuilding”. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.274.

Sanders, H.H. (1991). “Officials and citizens in international relations”. The Psychodynamics of International Relations. Volume 2.

Simplilearn. (2024, November 20). Learn Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches with Examples. Retrieved January 25, 2025, from https://www.simplilearn.com/top-down-approach-vs-bottom-up-approach-article.

What is Strategic Peacebuilding? Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. Retrieved January 26, 2025, from kroc.nd.edu/about-us/what-is-peace-studies/what-is-strategic-peacebuilding/.

NOTE:

[1] Dialogue can take various forms depending on the context. Indirect dialogue conveys messages without using direct quotes, while direct dialogue uses quotations to reproduce exact words. Informal dialogue is casual and relaxed, whereas formal dialogue adheres to rules to effectively address conflicting opinions.

_______________________________________________

Prof. Bishnu Pathak was a former Senior Commissioner at the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP), Nepal who has been a Noble Peace prize nominee 2013-2019 for his noble finding of Peace-Conflict Lifecycle similar to the ecosystem. A Board Member of the TRANSCEND Peace University holds a Ph.D. in interdisciplinary Conflict Transformation and Human Rights in two decades. Arduous Dr. Pathak who is an author of over 100 international paper-book publications has been used as references in more than 100 countries across the globe. Immense versatile personality Dr. Pathak’s publications belong to Human Rights, Human Security, Peace, Conflict Transformation, and Transitional Justices among others. He can be reached at ciedpnp@gmail.com.

Tags: Magna Carta, Magna Carta of Peace, Transitional Justice, UK

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 24 Mar 2025.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Magna Carta of Peace, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

7 Responses to “Magna Carta of Peace”

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.

Dear Bishnu,

This is a wonderful magna carta of peace and a real blueprint for a peace process for all.

Thank you for your inspiring work.

Peace,

Thank you very much, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Mairead.

https://nepaltoday.com.np/politics/13954

Thank you very much, Mr. Rajan Karki

I have read it thoroughly and truly its a wonderful craft from you which has very high significance in present days and more specifically for nextgen scholars and HRS. My brief comments or expressions reamins as follows, which I will try to share in some of mine destinations,

The paper “Magna Carta of Peace” presents a thought-provoking framework for conflict resolution, peacebuilding, and transitional justice through a structured, multi-track dialogue approach. Emphasizing a bottom-up strategy, it advocates for grassroots engagement in peace processes, ensuring the direct involvement of marginalized communities in conflict transformation. The integration of peacekeeping, peacemaking, and peacebuilding into a cohesive methodology underscores the significance of diplomacy, reconciliation, and reculturation in post-conflict societies. The discussion on the Unarmed Civilian Protection Force (UCPF) effectively highlights a non-military, community-driven approach to violence mitigation. While the paper offers valuable insights rooted in personal experience and practical observation, a clearer distinction between theoretical foundations and empirical findings could strengthen its academic rigor. Additionally, further elaboration on the real-world applications of the proposed framework would enhance its impact in contemporary peace efforts. A big congratulation for writer Prof Bishnu Pathak ji , to make it so simple, catchy and interesting that even a person like me , who do not have wisdom on such subject lines keeps engaged in reading and understanding it and commenting herein

Regards

Dr M L Gaur

VC, Dr C V Raman University Vaishali Bihar

Clicking “upload” in the top bar of Academia.edu, or the “upload” button on your profile, will start you on the process of adding a piece of research to Academia.

Please let us know if we can help with anything else!

You can also check out our help center article here!

Thanks!

Alberto (he/him)

Academia Customer Support

Vary innovative approach, congrats.