The Rohingya Crisis Shames the Global Community

ASIA--PACIFIC, 18 Dec 2017

11 Dec 2017 – The international response to the Rohingya crisis has been high on emotion, but depressingly low on action. As the Myanmar military began its latest “clearance operations” against the long-oppressed Muslim minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine state in August – pillaging villages, burning crops, and shooting civilians on sight – global media responded in admirable fashion. Within days, witness accounts and heart-wrenching photographs were relayed around the world.

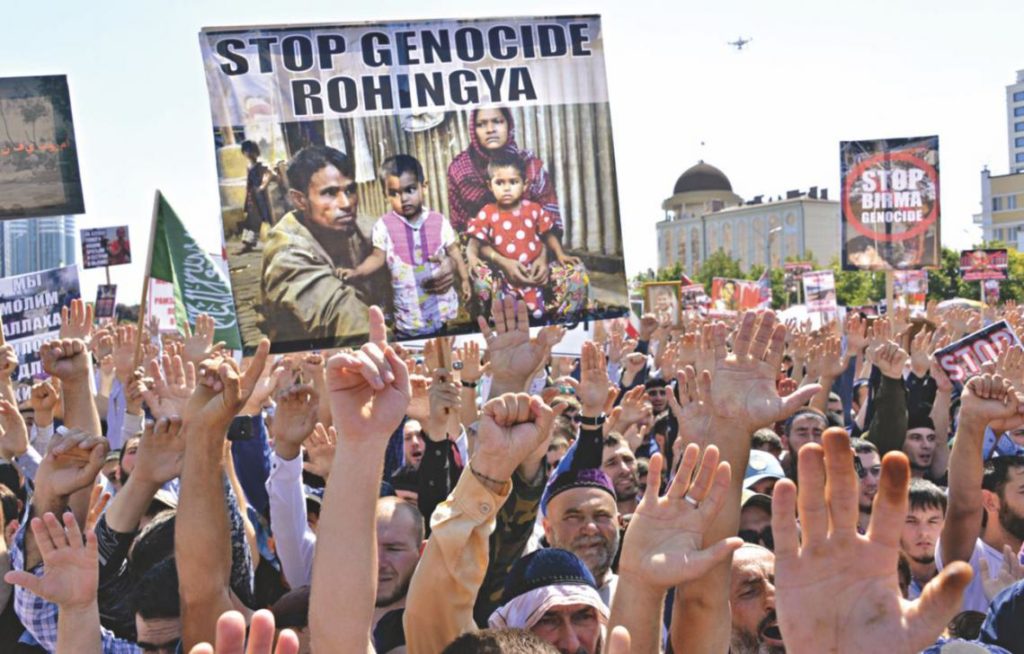

People take part in a rally in support of Myanmar’s stateless Rohingya minority in the Chechen capital of Grozny, Russia,on September 4, 2017. PHOTO: Reuters

But any hope that elevating the Rohingya’s plight into the public consciousness would lead to decisive action soon faded. By early September, as the death toll and the number of displaced persons rose, it became clear that the only reaction the international community could muster was condemnation – yet again, a damning indictment of our global institutional architecture.

Politicians quite rightly criticized the Myanmar military, known as the Tatmadaw. But that only precipitated a rush to express concern, and register anger. The media were far more interested in the Hollywood-esque story that human-rights icon Aung San Suu Kyi – who failed to act – had fallen from grace. And while attention was focused on waiting for Myanmar’s de facto leader to do something, policy prescriptions and in-depth insights on ending, or managing, the crisis were relegated to non-governmental organizations’ blogs, as politicians and diplomats bumbled on.

Indeed, public discourse is often a barometer for what’s happening at the policy level. And the necessary early push toward solutions was hijacked by the world’s collective outrage. Much energy was directed toward whether Suu Kyi should have her Nobel Peace Prize revoked, asking why she wasn’t acting, or pussyfooting over whether the Tatmadaw’s actions constituted genocide or ethnic cleansing.

Platitudes, anger, and pontification wasted valuable time. It took until September 19 – four weeks after the atrocities began – for the UK Ministry of Defense simply to announce it would stop training and supporting the Tatmadaw. And it was not until 500,000 Rohingya had fled for Bangladesh that the United Nations Security Council held its first public meeting on the situation. It was only at the end of September when the world began to realize that Suu Kyi, willingly or unwillingly, had her hands tied.

While humanitarian support for the displaced Rohingya in Bangladesh grew, Rakhine remained on lockdown. And any action that did take place was bilateral.

A weak understanding of the nation’s politics meant considerable time was wasted on waiting for Suu Kyi to act. Sanctions may now only bring the largely anti-Muslim population of Myanmar and the military closely together

In mid-October, the European Union Council of Foreign Ministers annulled ties and incorporated travel bans for the Myanmar military, as did the United States. Both also began reviewing the possibility of further formal sanctions. Meanwhile the Pope’s late-November visit to Myanmar to denounce the violence must have hit home to the Rohingya just how helpless the West had become.

Of course, solutions to the conflict are not simple, or easy to coordinate. But a weak understanding of the nation’s politics meant considerable time was wasted on waiting for Suu Kyi to act. Sanctions may now only bring the largely anti-Muslim population of Myanmar and the military closely together. And with their veto power on the UN Security Council, China, Myanmar’s ally, and Russia have limited the most powerful multilateral institution to words of condemnation. Another world power, India, has meanwhile tacitly supported the Myanmar military’s actions.

As such, it has now become “one of the fastest refugee exoduses in modern times and has created the largest refugee camp in the world,” according to the International Crisis Group. In reality, boots on the ground to defend the Rohingya are the only things that would have assuaged the military onslaught. And subsequently, support for empowering the government to enact the recommendations of the Kofi Annan-led Advisory Commission on Rakhine State would be a constructive course. That won’t be easy – but it is better than defeatism and helplessness.

Indeed, the crisis underscores how the international community, after decades of experience, still does not have the resources, coordination, and intelligence to act – partly because the UN lacks rapidly decisive, independent, and well-equipped institutional teeth. And as such, emotion and national politics – and crucially, not concerted reason –tend to define policy in times of conflict.

We may say “never again.” But without reform and rethinking how we react, we’re only doomed to keep repeating the same cycle: condemnation, anger, calls for action, insufficient action, and, then, shame.

_________________________________________________

Tej Parikh is a global policy analyst and journalist. He received his master’s degree from Yale University with a focus on state building, political economy, and conflict. He runs The Global Prism a centrist international affairs platform.

Tej Parikh is a global policy analyst and journalist. He received his master’s degree from Yale University with a focus on state building, political economy, and conflict. He runs The Global Prism a centrist international affairs platform.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.