Where Do the Names of Our Months Come From?

TRIVIA, 15 Jan 2018

Caillan Davenport - The Conversation

10 Jan 2018 – Our lives run on Roman time. Birthdays, wedding anniversaries, and public holidays are regulated by Pope Gregory XIII’s Gregorian Calendar, which is itself a modification of Julius Caesar’s calendar introduced in 45 B.C. The names of our months are therefore derived from the Roman gods, leaders, festivals, and numbers. If you’ve ever wondered why our 12-month year ends with September, October, November, and December – names which mean the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth months – you can blame the Romans.

The calendar of Romulus

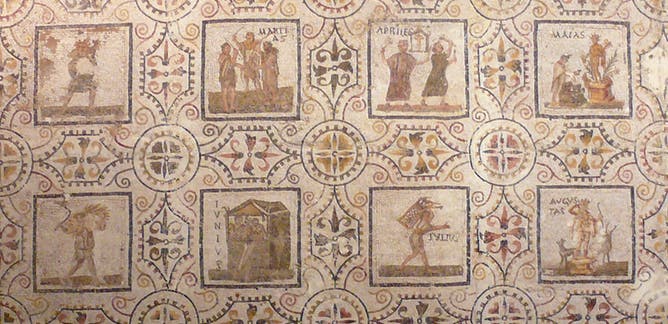

The Roman year originally had ten months, a calendar which was ascribed to the legendary first king, Romulus. Tradition had it that Romulus named the first month, Martius, after his own father, Mars, the god of war. This month was followed by Aprilis, Maius, and Iunius, names derived from deities or aspects of Roman culture. Thereafter, however, the months were simply called the fifth month (Quintilis), sixth month (Sixtilis) and so on, all the way through to the tenth month, December.

The institution of two additional months, Ianuarius and Februarius, at the beginning of the year was attributed to Numa, the second king of Rome. Despite the fact that there were now 12 months in the Roman year, the numerical names of the later months were left unchanged.

Further reading: Explainer: the gods behind the days of the week

Gods and rituals

While January takes its name from Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings, February comes from the word februum (purification) and februa, the rites or instruments used for purification. These formed part of preparations for the coming of Spring in the northern hemisphere.

The februa included spelt and salt for cleaning houses, leaves worn by priests, and strips of goat skin. These strips were put to good use in the festival of the Lupercalia, held each year on February 15. Young men, naked except for a goat-skin cape, dashed around Rome’s sacred boundary playfully whipping women with the strips. This ancient nudie run was designed to purify the city and promote fertility.

The origins of some months were debated even by the Romans themselves. One tradition had it that Romulus named April after the goddess Aphrodite, who was born from the sea’s foam (aphros in Ancient Greek). Aphrodite, known as Venus to the Romans, was the mother of Aeneas, who fled from Troy to Italy and founded the Roman race. The other version was that the month derived from Latin verb aperio, “I open”. As the poet Ovid wrote:

For they say that April was named from the open season, because spring then opens all things, and the sharp frost-bound cold departs, and earth unlocks her teeming soil …

There were similar debates about the origins of May and June. There was a story that Romulus named them after the two divisions of the Roman male citizen body, the maiores (elders) and iuniores (juniors). However, it was also believed that their names came from deities. The nymph Maia, who was assimilated with the earth, gave her name to May, while Juno, the goddess of war and women, was honoured by the month of June.

Imperial pretensions

The numerical names of the months in the second half of the year remained unchanged until the end of the Roman Republic. In 44 B.C., Quintilis was rebranded as Iulius, to celebrate the month in which the dictator Julius Caesar was born.

This change survived Caesar’s assassination (and the outrage of the orator M. Tullius Cicero, who complained about it in his letters). In 8 B.C., Caesar’s adoptive son and heir, the emperor Augustus, had Sextilis renamed in his honour. This was not his birth month (which was September), but the month when he first became consul and subjugated Egypt.

This change left four months – September, October, November and December – for later emperors to appropriate, though none of their new names survive today. Domitian renamed September, the month he became emperor, to Germanicus, in honour of his victory over Germany, while October, his birthday month, he modestly retitled Domitianus, after himself.

Further reading: Explainer: the seasonal calendars of Indigenous Australia

However, Domitian’s arrogance paled in comparison with the megalomaniacal Commodus, who rebranded all the months with his own imperial titles, including Amazonius (January) and Herculeus (October).

If these titles had survived Commodus’s death, we would not have the problem of our year ending with months carrying the wrong numerical names. But we would be celebrating Christmas on the 25th of Exsuperatorius (“All-Surpassing Conqueror”).

_____________________________________________

Caillan Davenport – Senior Lecturer in Roman History, Macquarie University

Caillan Davenport – Senior Lecturer in Roman History, Macquarie University

Republish The Conversation articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons license.

Go to Original – theconversation.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.