Drawing Palestine from Prison: The Artwork of Palestinian Cartoonist Mohammad Sabaaneh

PALESTINE - ISRAEL, ARTS, 19 Mar 2018

“Most artists describe the Palestinian as a hero, even if imprisoned or killed by Israelis. I prefer to convey the message that Palestinians are human beings, so I portray suffering. The hero does not need anyone to stand with him — the hero is strong — but human beings need and demand someone to show solidarity with them.”

12 Mar 2018 — Mohammad Sabaaneh’s incisive artwork has earned him a barrage of antagonism from Israel and Palestinian political factions. In February 2013, he was issued an administrative detention order by Israel and jailed for five months for alleged association with Hamas through his artwork. Some of his cartoons were published in a book written by Sabaaneh’s brother, who is affiliated with Hamas. Israel defined his contribution to the book as “collaboration with Hamas.”

Sabaaneh’s experience is reminiscent of other Israeli efforts to target freedom of expression. Palestinian media is regularly targeted, including direct attacks on journalists through physical aggression and detention. With the Palestinian Authority following suit since passing its Cybercrime Law, avenues for Palestinian independent expression entail censorship risks and punitive measures.

Sabaaneh grew up in Kuwait as part of the Palestinian diaspora, returning to Palestine in September 2000 before the commencement of the Second Intifada. Sabaaneh’s return to Palestine wrought new perspectives on Palestinians resistance and enabled him to discern the difference between the image of the Palestinian prisoner as a “hero” from the outside and the actual human existence of Palestinian political prisoners.

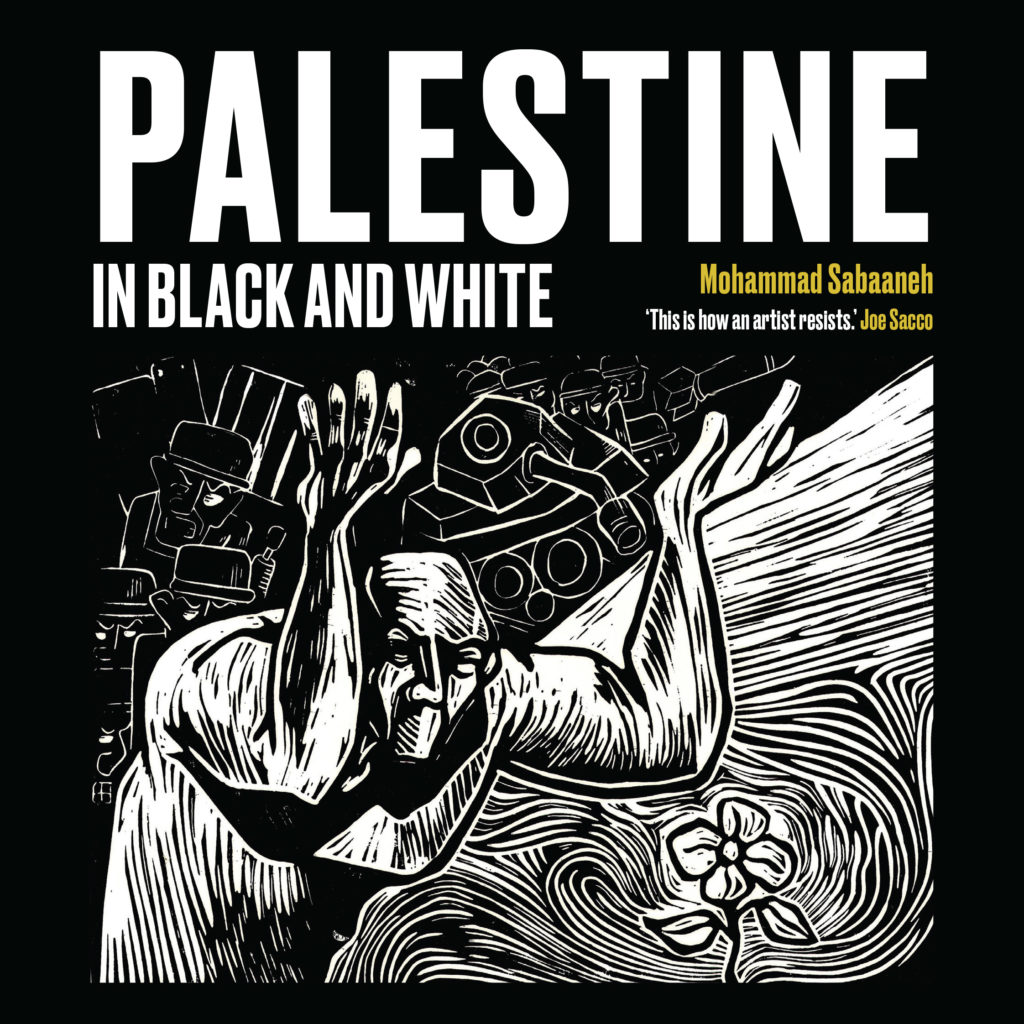

When Israel imprisoned him, sharing a fate similar to that of other Palestinian political prisoners contributed to a new approach in his artistic expression. While in solitary confinement for two weeks, Sabaaneh sought to transcend the dehumanization, embarking upon an art project that he planned to exhibit upon his release and that has now been published as a book titled Palestine in Black and White.

“Enemy of the prison”

Speaking to MintPress News, Sabaaneh describes his experience of isolation while imprisoned by Israel, and his efforts at countering this torture technique:

In Israeli prisons, they torture prisoners by putting them in isolation for long periods of time. During this time, the prisoner cannot talk with, or see, anyone. It is during this time that the prisoner becomes the enemy of the prison.”

He explains further:

I decided to make some artwork to while away these long stretches of time inside the prison, with the intention of exhibiting the art when I was released. The artwork was about Palestinian prisoners, about suffering, questioning and investigations, and family visits.”

To avoid scrutiny, Sabaaneh explains that he drew cartoons without detail:

This was so that nothing would indicate that I was drawing cartoons about prison experience. For example, I drew prison windows without bars and left the speech bubbles empty, without dialogue. This was so that in case of discovery by the prison authorities, they would not recognize the subject as the prison. When prisoners were released, I would smuggle the cartoons out with them. Upon my release I completed the collection and they are now published in a book.”

The humanity of Palestinian prisoners

Sabaaneh’s cartoons are multi-layered and compel the viewer to approach them comprehensively in context. One of his main subjects is the concept of the Palestinian prisoner. The mainstream narrative, even within Palestine, is the glorification of the Palestinian prisoner as a “hero.”

The association with glorification is not without reason. The practice of administrative detention, which is allowed in international law under exceptional circumstances, has been used by Israel to target any form of Palestinian resistance by detaining individuals indefinitely and renewing their detention periods.

Last month, the Palestinian NGO Addameer released statistics regarding the number of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails. The total number of Palestinian political prisoners reached 6,119 by March 2018, while there are currently 450 Palestinians held under administrative detention orders.

Wafa news agency reported the Palestinian Prisoners’ Society (PPS) as stating that, as of the beginning of March 2018, the number of administrative detention orders issued this year had risen to 116.

Without diminishing the status attributed to Palestinian prisoners, Sabaaneh insists upon viewing the human being behind the glorification. On its own, the “hero” image becomes an isolated burden — an identity assumed by the prisoner that is incomplete.

Sabaaneh emphasizes the danger of such detachment between the imposed image and the human being, in this case the Palestinian prisoner:

Yes, they are heroes, but what they are facing is the unethical. Inside the prisons, the prisoners suffer as human beings. To be honest with you, that was what I felt when I was locked in a small bathroom in the Algalami detention center. They wanted to torture and humiliate me. Yes, I was strong in front of the interrogators and soldiers, but inside I missed my life, my art, my place and my family. And I think that is what we should convey to our audience.”

The art depicting Sabaaneh’s statement is impactful. In one cartoon drawing, titled “Families of political prisoners are prisoners too,” he shows the ramifications of incarceration upon the family, something that is often forgotten when the focus is placed exclusively upon the prisoner. There is a link between the prisoner and the family that can be lost in mainstream narratives and that contributes to the isolation of the individuals concerned. This is an anomaly, considering that the experience of imprisonment is also a collective experience for Palestinians resisting Israel’s colonial military occupation.

Sabaaneh also believes that “the artist can choose his role.” This is particularly important when it comes to creating art that narrates the Palestinian experience and trauma. Keeping to the depiction of Palestinian prisoners, he explains the difference between his expression and that of the mainstream:

Most artists describe the Palestinian as a hero, even if imprisoned or killed by Israelis. Personally, I prefer to convey the message that Palestinians are human beings, so I portray suffering. The hero does not need anyone to stand with him — the hero is strong — but human beings need and demand someone to show solidarity with them.”

He goes on to explain another discrepancy between artistic depiction and reality:

I cannot understand how we can draw children in Israeli prisons as heroes, for example. The stark cartoons in my book convey the reality of the situation and of real people’s lives. In standing with my own people, I will not neglect the duty of explaining the true situation to the people around the world.”

Censorship and checkpoints

Conveying an understanding of the implosion experienced by Palestinians, Sabaaneh draws upon two experiences — the reactions of the Israeli government and Palestinian factions to his art, and the experience of living under Israel’s military occupation.

Israel, he says, “attack every cartoon I make. They stop me for hours at the border when I travel.”

The Palestinian Authority turned out to be no different. In 2015, as a response to the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, Sabaaneh drew a cartoon showing a figure standing on top of the earth, which was interpreted as the artist drawing the Prophet Mohammed. Palestinian Authority leader Mahmoud Abbas ordered an investigation into the cartoon, which Sabaaneh says was misinterpreted.

Conversely, Abbas had travelled to Paris with other world leaders, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, for a march in solidarity for press freedom in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo killings. Six months earlier, in the summer of 2014, Netanyahu had launched Operation Protective Edge against Gaza, killing over 2,000 Palestinian civilians. Prior to the march in Paris, Netanyahu manipulated the narrative on freedom of expression to insist:

Israel is being attacked by the very same forces that attack Europe. Israel stands with Europe. Europe must stand with Israel.”

With Palestinians, Abbas has encroached upon freedom of expression — which culminated last year with the Cybercrime Law, largely seen as the means through which the Palestinian Authority can stifle dissent.

Sabaaneh stressed that his art is critical of all Palestinian factions:

In Palestine, the political factions level charges of supporting Hamas, or denigrating faith, to attack my art through social media. Once I received death threat because of my cartoons. It is the hardest for me when I am attacked by my own people.”

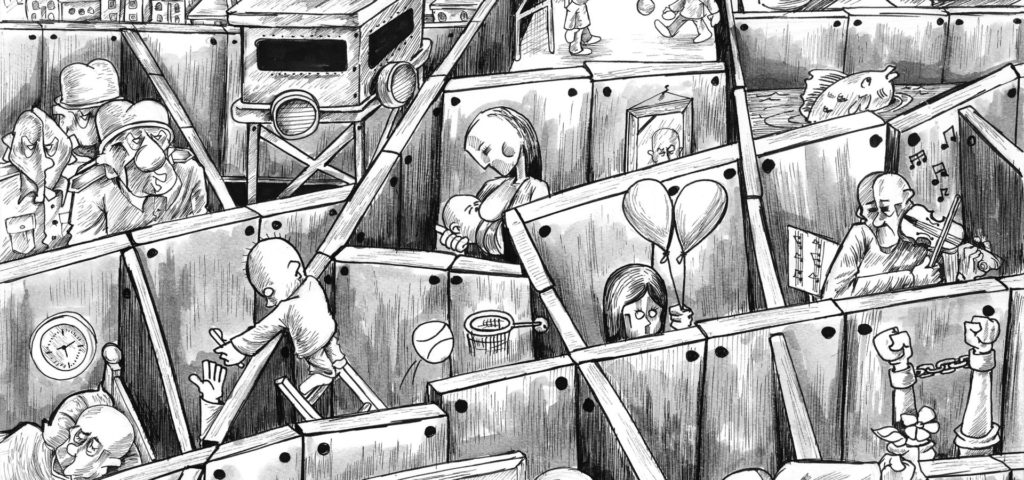

One of Sabaaneh’s cartoons, titled “Lives Interrupted,” portrays the restrictions experienced by Palestinians. It shows Palestinians living life in enclosed spaces with little prospect of communication or movement.

Sabaaneh explains his artistic approach towards these restrictions. He insists that his art is also an emotional expression, or reaction to the human rights violations around him:

I reflect what I feel in my art. I do not decide what to draw when I draw anything. What I know is how stark and dense my artwork in the book is. How I feel it reflects my life.”

Sabaaneh’s words are a reminder of the February 2018 press release by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the occupied Palestinian territory (OCHA), detailing the freedom-of-movement restrictions for Palestinians in Hebron City. It cites “over 100 physical obstacles, including 20 checkpoints” as part of the segregation imposed upon Palestinians. Restrictions in the name of purported security concerns, OCHA stated, has turned “a once thriving area into a ghost town.”

In his art, Sabaaneh reflects these human rights violations: the indignity of checkpoints, military incursions that throttle Palestinian freedom, the Apartheid Wall, and exploitation of labor. His art brings together the Palestinian experience, which is usually summarised in ways that detract from its social and psychological ramifications. He emphasized:

When you travel from any city in the West Bank to another, you will understand what I mean. You will face checkpoints; then you will face settlements; then you will face the segregation wall; then another checkpoint.”

And of the human aspect, Sabaaneh ruminates further:

When you enter a Palestinian city you will meet former prisoners. Then you will see the house of a martyr and posters of him on the wall of a nearby street.”

What of the artistic response to the humanitarian aspect of the political violence suffered by Palestinians? Sabaaneh is unequivocal:

Your artistic response will be explosive. If it is not, then you are not an artist and you are not human. There is no need to decide what you want to talk about in your art. Your feeling will lead you.”

_________________________________________________

Ramona Wadi is an independent researcher, freelance journalist, book reviewer, and blogger. She writes about the struggle for memory in Palestine and Chile, historical legitimacy, the ramifications of settler-colonialism, the correlation between humanitarian aid and human rights abuses, the United Nations as an imperialist organisation, indigenous resistance, la nueva cancion Chilena and Latin American revolutionary philosophy with a particular focus on Fidel Castro, Jose Marti and Jose Carlos Mariategui. Her articles, book reviews, interviews, and blogs have been published in Middle East Monitor, Upside Down World, Truthout, Irish Left Review, Gramsci Oggi, Cubarte, Rabble.ca, Toward Freedom, History Today, Chileno and other outlets, including academic publications and translations into several languages.

Go to Original – mintpressnews.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

PALESTINE - ISRAEL:

- Israel Is About to Empty Gaza

- The Israeli Army Is Facing Its Biggest Refusal Crisis in Decades

- Israeli Troops Blow Whistle on War Crimes in Gaza ‘Kill Zone’

ARTS: