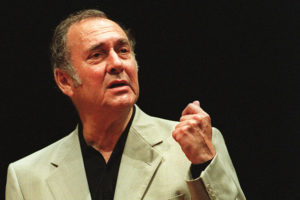

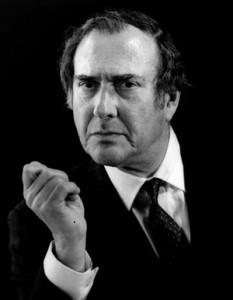

Harold Pinter (10 Oct 1930 – 24 Dec 2008)

BIOGRAPHIES, 8 Oct 2018

Biography – TRANSCEND Media Service

Born in London in 1930, Harold Pinter is a renowned playwright and screenwriter. His plays are particularly famous for their use of understatement to convey characters’ thoughts and feelings. In 2005, Pinter was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Early Life

Writer and political activist Harold Pinter is most famous for his plays. Inspired in part by Samuel Beckett, he created his own distinctive style, marked by terse dialogue and meaningful pauses. He was the son of a Jewish tailor and grew up in a lower middle-class neighborhood in London. In his grammar school years, Pinter was athletic and especially fond of playing cricket.

During World War II, Pinter saw some of the bombing of his city by the Germans. He was sent away to escape the Blitz at one point. This firsthand experience of war and destruction left a lasting impression on Pinter. At the age of 18, he refused to enlist in the military as part of his national service. A conscientious objector, he ended up paying a fine for not completing his national service.

Pinter started out as an actor. After studying at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art for a time, he worked in regional theater in the 1950s and sometimes used the stage name David Baron. Pinter wrote a short play, The Room, in 1957, and went on to create his first full-length drama, The Birthday Party. The Birthday Party premiered in London in 1958 to savage reviews, and closed within a week. One critic, Harold Hobson of The Sunday Times of London, offered a dissenting opinion, writing that Pinter was “the most original, disturbing and arresting talent in theatrical London,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

Major Works

With 1960’s The Caretaker, Pinter had his first taste of success. The play is about two brothers who bring home a homeless man to live with them—a man who then exerts a strange hold over the brothers. The play, like many of Pinter’s works, conveys “a world of perplexing menace,” and in it Pinter uses “a vocabulary all his own,” as a critic for The New York Times once explained.

The Homecoming (1965), considered by some to be his masterwork, explored familial tensions. In the play, a man brings his wife to meet his father and brothers after a long estrangement. The wife ends up leaving him to stay with his family. The drama moved to Broadway in 1967 and won a Tony Award—Pinter’s only Broadway honor. The Homecoming was later turned into a film featuring many of its original cast, including Ian Holm, Terence Rigby and Vivien Merchant. Pinter had met Merchant when he was working as an actor, and the couple had married in 1956.

Around this time, Pinter also branched out into film, writing the screenplays for his own works as well as the works of others. He wrote The Servant (1963) and Accident (1967), both directed by Joseph Losey and starring Dirk Bogarde. Losey and Pinter worked together on one more film—1970’s The Go-Between, starring Julie Christie and Alan Bates. Perhaps one of Pinter’s best-known screen adaptations was 1981’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman, starring Jeremy Irons and Meryl Streep.

In 1978, Pinter brought to the stage another of his best-regarded works, the drama Betrayal. This tale of infidelity and marital meltdown seemed to reflect the writer’s life in some ways, in particular his affair with TV personality Joan Blakewell. He was later involved with Lady Antonia Fraser who was married to a member of Parliament and a mother of six. The pair were eventually able to shed their respective spouses and married in 1980. Pinter and Fraser, a talented writer in her own right, became a very popular couple in literary circles.

Pinter’s politics became more explicit in his late works. The short play Mountain Language (1988), for instance, was written to highlight the mistreatment of the Kurdish people in Turkey. He and fellow playwright Arthur Miller had visited Turkey together a few years earlier.

Death and Legacy

After being diagnosed with cancer in 2001, Pinter continued his writing and activism. He decried Britain’s involvement in the Iraq War, and he called both U.S. President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair “terrorists,” according to the Financial Times. Pinter expressed some of his outrage in his poetry, particularly his 2003 collection, WAR. In a poem entitled “God Bless America,” he wrote:

“Here they go again/ The Yanks in their armoured parade/ Chanting their ballads of joy/ As they gallop across the big world/ Praising America’s God/ The gutters are clogged with the dead.”

These political reflections helped Pinter earn the Wilfred Owen Award for poetry.

In 2005, Pinter was honored with the Nobel Prize for Literature. The selection committee cited Pinter a writer “who, in his plays, uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression’s closed rooms.” Some saw the choice of Pinter, an antiwar campaigner, as a political statement. He wasn’t well enough to accept the prize in person, and he gave his Nobel lecture in a pre-recorded video played at the event.

Pinter succumbed to cancer on December 24, 2008. He was survived by his second wife, writer Antonia Fraser, his son from his first marriage, Daniel, and his six stepchildren.

Pinter’s work has inspired and informed generations of playwrights, especially Tom Stoppard and David Mamet. Pinter’s plays are still performed around the world, with new audiences experiencing the distinct, strange and foreboding atmosphere so often created by the late writer. Of Pinter, fellow playwright David Hare once said, “The essence of Pinter’s singular appeal is that you sit down to every play he writes in certain expectation of the unexpected,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

Go to Original – biography.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.