Socialism or Barbarism in Brazil, According to Boaventura de Sousa Santos

BRICS, 24 Dec 2018

Beverly Goldberg and Francesc Badia i Dalmases | Open Democracy – TRANSCEND Media Service

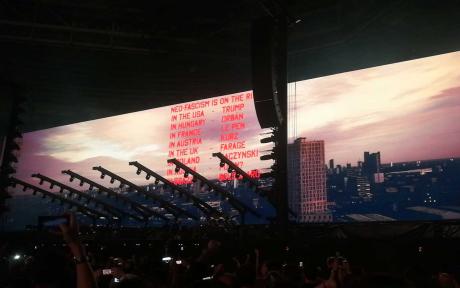

The crisis of the left around the world has opened up a vacuum for extreme right movements to gain traction and threaten our democracies. How does Boaventura de Sousa Santos makes sense of this in Brazil?

17 Dec 2018 – The crisis of the left around the world has opened up a vacuum for extreme right movements to gain traction and threaten our democracies.

What Francis Fukuyama called the ‘end of history’ after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, in other words, the end of the fight between the ideologies of the left and the right in the post-Cold War world, and the triumph of liberal democracy as the only political path, lost its relevance thirty years later.

One of the most influential modern thinkers that has positioned himself against this idea of the end of history is Portuguese sociologist, Boaventura de Sousa Santos.

De Sousa Santos has pointed out that the democratic decline that we are currently experiencing, and the solution to said decline, has everything to do with ideology.

In his recent book “Left of the world, unite!”, he analyses various cases of democratic decline around the world and proposes a solution: only a union of left wing forces is capable of containing the capitalist system that has eroded the civil, human and political rights of the marginalised classes in the world over the years.

Neoliberalism: a dark force

The key point in De Sousa Santo’s argument is that whilst previously, democracy was a force that was able to contain capitalism by creating a system of controls that involved state intervention in the economy to mitigate the most unforgiving abuses of the financial regime, now the tables have turned.

What we now see is a type of neoliberal capitalism that controls our democracies, and that shapes them according to the needs of the market and the financial elites.

For De Sousa Santos, this evolution towards an unforgiving neoliberalist strain of capitalism is natural, given that capitalism is intrinsically incompatible with democracy.

Capitalism due to its very nature, constantly seeks greater accumulation of wealth and goods, and consequently depends on a structure that includes some and excludes others.

Democracy on the other hand seeks the greatest level of citizen participation possible and a widening of both political and human rights.

To understand the evolutions that we are currently experiencing, it is essential to understand the three axes of domination that generate the inequalities that characterise the current social system: capitalism, colonialism, and the patriarchy.

Upon exporting and reinforcing privitisation and the primacy of the market, supported strongly by US imperialism, neoliberal globalisation facilitated the erosion of the social democratic state.

Colonialism, as a generator of race inequality, the patriarchy as a generator of gender inequality, and capitalism, as a generator of economic inequality and a reinforce of the other two axes.

Upon exporting and reinforcing privitisation and the primacy of the market, supported strongly by US imperialism, neoliberal globalisation facilitated the erosion of the social democratic state.

This US imperialism is not the same as that which John Pilger referred to in his documentary ‘The War on Democracy’ a decade ago.

His reports of impositions of dictatorships and of invasions by military forces propped up by the CIA in Latin America correspond to a situation that has developed into an equally invasive threat today.

It may appear more subtle in nature but it is certainly no less dangerous: the promotion and financing of “market friendly democracy initiatives through libertarian and evangelical non-governmental organisations”.

Democratic decline in Brazil and the deterioration of the left

Brazil is an example of how the inequalities that De Sousa Santos identifies can manifest themselves openly and savagely.

The country has one of the highest Gini coefficients in the world (a measure of inequality of the World Bank), and the highest of Latin America at 0,513 in 2015, and it has recently become the latest country to fall victim to the rise of the extreme right, with the presidential win of ex-military hard man Jair Bolsonaro, known for his racist, sexist, homophobic, and ultra-neoliberal positions.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and the Workers Party (PT) takes power for the first time in Brazil in 2002 with 61% of the votes and as the first left wing force to govern the country.

The PT arrive at the presidential palace as a moderate left-wing force that, through the years, had gradually lost its socialist character to become a party that defended increased state control of the economy, but also within the neoliberal capitalist system.

The empire of the PT would last until 2016 with the impeachment of ex-president Dilma Rousseff.

During 14 years of PT governance, the Gini coefficient improved by 8 points due to the introduction of redistributive policies, an increase in the minimum wage, and expansion of credit for the popular classes.

However, after being defeated by two far right leaders, Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro, the PT currently finds itself in the most acute crisis it has experienced to this date.

Some analysts have even attributed the results of the last election to the fact that the levels of rejection of the PT (antipetismo) were higher than the levels of support for Bolsonaro, catapulting him to victory.

The causes are complex and it is important to understand what such a drastic change will mean in real terms for Brazil.

De Sousa Santos identifies the existence of the ‘deep Brazil’, that he also describes as the invisible Brazil, where the disappointment of the marginalised and impoverished majority seemingly became one of the main sources of antipetismo.

In his analysis, he claims that this majority had no access to political discourse, and in this context, evangelical churches would act to replace this absence.

This majority felt abandoned by the governments of the PT, and suffered the great environmental and human costs incurred throughout the implementation of their social and developmental policies relating to mining, agribusiness, and mega-projects such as hydroelectric dams, and the stadiums built for the Olympic Games and the World Cup.

On many occasions, the PT, although it defined itself as a party of the left, operated within the same neoliberal frameworks that their right-wing counterparts openly promote.

For example, during the governments of Lula and Rousseff, the contruction of the Belo Monte dam was carried out in the river Xingú on indigenous territory, without respecting the right of these communities to prior consultation.

This disappointment with the PT could be seen even before the previous elections, when the public survey on voter intention by DataFolha from the 10th of October showed that indigenous voters preferred Bolsonaro by 41% to 37% for Haddad.

Even though the Federal Court of the region declared that the project was inconstitutional, the Supreme Court returned the licence to the construction company and demanded the works immediately recommence as the economic effects on Brazil of its non-construction would be significant.

This disappointment with the PT could be seen even before the previous elections, when the public survey on voter intention by DataFolha from the 10th of October showed that indigenous voters preferred Bolsonaro by 41% to 37% for Haddad.

The role of the US and democratic decline

De Sousa Santos indicates that neoliberal imperial intervention originating from the US influenced decisively the results of the Brazilian elections.

US millionaires with strong interests in deterring state interference in the economy, redistribution, and development projects, felt that the country had to regress back to the neoliberal market that once determined its functioning so that US companies could exploit natural resources and access the free market according to their needs.

One of the main pillars of this imperial intervention is the incitement of social protest through social media, using civil institutions and organisations to represent their interests with fake news and misinformation.

Together with this pillar is that of intervention in the judicial system, which managed to implant a highly politicised anti-corruption investigation, Lava Jato, that sent Lula da Silva to jail whilst leaving many politicians of the right equally accused of corruption completely untouched.

Fake news spread across social networks have been the protagonist of these past elections in Brazil. The role of the US in this process is ambiguous yet present nonetheless.

An investigation by Mídia Ninja demonstrated that many WhatsApp groups that were spreading fake news in favour of Bolsonaro originated in the US, and the far-right figure who decisively intervened in the election of Trump by spreading fake news en masse, Steve Bannon, met with Eduardo Bolsonaro and they agreed that Bannon would advise him throughout his father’s campaign.

What De Sousa Santos fails to address is the complicity of the Brazilian elites in the continued spinning of the US funded neoliberal wheel of fortune whether or not they have direct links to the US, and without which a far-right victory would have been impossible.

An investigation by the BBC shows that there were far more fake news groups in favour of Bolsonaro on WhatsApp than for any other candidate, meanwhile the Caixa2 scandal revealed an extensive network of Brazilian entrepreneurs paying millions of dollars to flood social media and WhatsApp with fake news against Haddad.

Brazilian sociologist Luiz Alberto de Vianna Moniz Bandeira for example has denounced the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in 2016 as a process driven by strong US interests that sought to reinforce its hegemony before negotiating the construction of two naval bases in Argentina.

Wall street funds arrived swiftly in the country to secure the success of the impeachment. Sergio Moro, the judge who led the investigation and who incarcerated Lula da Silva has strong links to the US.

The causes of this democratic decline that Brazil and the entire world are suffering are multiple, however, the solution that de Sousa Santos proposes is this: a union of left-wing forces that protect human rights and state intervention in the economy

He completed a program on combating international corruption at Harvard, and since then, has travelled frequently to the US. Now, he has been named Bolsonaro’s justice minister.

The causes of this democratic decline that Brazil and the entire world are suffering are multiple, however, the solution that de Sousa Santos proposes is this: a union of left-wing forces that protect human rights and state intervention in the economy, with the intention of counteracting the most dehumanising effects of neoliberalism.

However, in a multiparty system as diverse as that of Brazil (there are currently more than 30 different parties in the House of Representatives), and where the left is highly divided between those who believe in the hegemony of the PT and those who demand a change, a united force of the left is unlikely.

A left that has been caught up in discussions over its multiple identities is ultimately vulnerable up against a right that knows how to successfully define itself by what it is not: communist.

The dilemma of socialism or barbarism that De Sousa Santos has posed may seem exaggerated and dichotomist, with undertones of anti-US imperialism that appears somewhat contrasting to the current isolationist trend promoted by Trump.

Savage and colonializing capitalism today is also dealt by Chinese and Russian hands, equally felt by Latin America today.

Boaventura could not be more right that this state of dangerous democratic decline that is currently tearing through Brazil, can only be combated through constructive self-criticism and a union of left wing forces that can overcome the hegemony of the PT, together with the recognition that history did not end with the Cold War as Fukuyama suggested, but is it more alive than ever, at the very least in the context of southern epistemologies.

______________________________________________

Boaventura de Sousa Santos is Professor of Sociology, University of Coimbra (Portugal), and Distinguished Legal Scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. He earned an LL.M and J.S.D. from Yale University and holds the Degree of Doctor of Laws, Honoris Causa, by McGill University. He is director of the Center for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra and has written and published widely on the issues of globalization, sociology of law and the state, epistemology, social movements and the World Social Forum. His most recent project ALICE: Leading Europe to a New Way of Sharing the World Experiences is funded by an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council. bsantos@ces.uc.pt

Boaventura de Sousa Santos is Professor of Sociology, University of Coimbra (Portugal), and Distinguished Legal Scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. He earned an LL.M and J.S.D. from Yale University and holds the Degree of Doctor of Laws, Honoris Causa, by McGill University. He is director of the Center for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra and has written and published widely on the issues of globalization, sociology of law and the state, epistemology, social movements and the World Social Forum. His most recent project ALICE: Leading Europe to a New Way of Sharing the World Experiences is funded by an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council. bsantos@ces.uc.pt

Graduate in Hispanic and Latin American Studies from the University of Glasgow, Beverly Goldberg is currently based in Barcelona, where she is interning for democraciaAbierta whilst completing a masters in International Relations.

Francesc Badia i Dalmases is Founder, Director and Lead Editor of democraciaAbierta. Francesc is an international affairs expert, journalist and political analyst. His most recent book: Order and disorder in the 21st century. Gobal governance in a world of anxieties.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.

Go to Original – opendemocracy.net

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.