Why the Assange Arrest Should Scare Reporters

MEDIA, 22 Apr 2019

The WikiLeaks founder will be tried in a real court for one thing, but for something else in the court of public opinion.

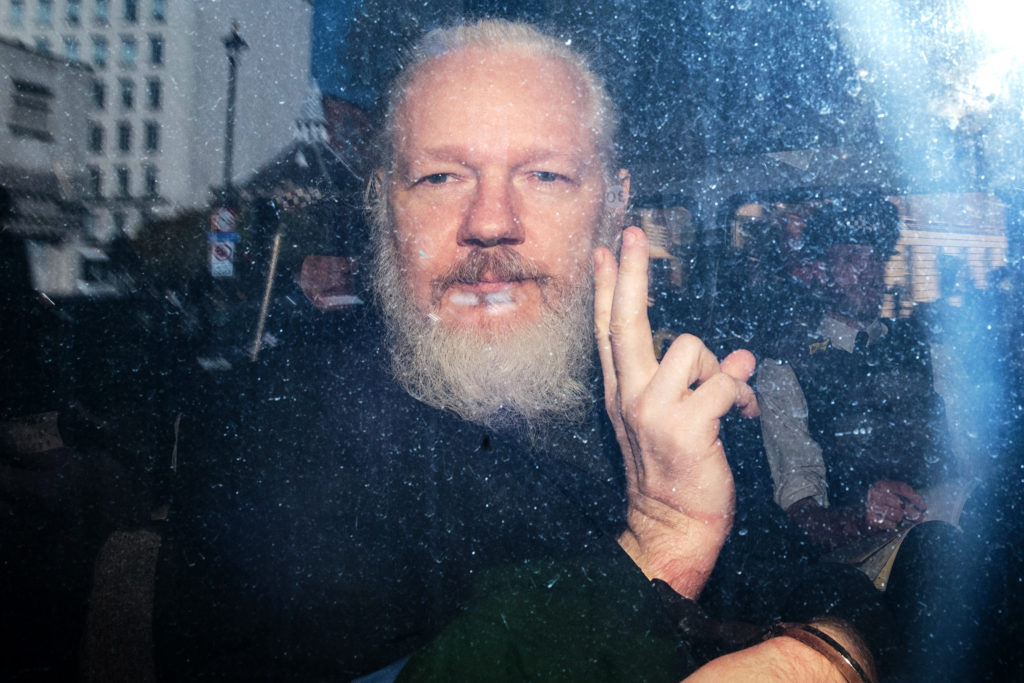

Julian Assange gestures to the media from a police vehicle on his arrival at Westminster Magistrates court on April 11, 2019 in London. After weeks of speculation WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was arrested by Scotland Yard Police Officers inside the Ecuadorian Embassy in Central London this morning. Ecuador’s President, Lenin Moreno, withdrew Assange’s Asylum after seven years citing repeated violations to international conventions.

Jack Taylor/Getty Images

11 Apr 2019 – Julian Assange was arrested in England on Thursday. Though nothing has been announced, there are reports he may be extradited to the United States to face charges related to Obama-era actions.

Here’s the Washington Post on the subject of prosecuting Assange:

“A conviction would also cause collateral damage to American media freedoms. It is difficult to distinguish Assange or WikiLeaks from The Washington Post.”

That passage is from a 2011 editorial, “Why the U.S. Shouldn’t Try Julian Assange.”

The Post editorial of years back is still relevant because Assange is being tried for an “offense” almost a decade old. What’s changed since is the public perception of him, and in a supreme irony it will be the government of Donald “I love WikiLeaks” Trump benefiting from a trick of time, to rally public support for a prosecution that officials hesitated to push in the Obama years.

Much of the American media audience views the arrested WikiLeaks founder through the lens of the 2016 election, after which he was denounced as a Russian cutout who threw an election for Trump.

But the current indictment is the extension of a years-long effort, pre-dating Trump, to construct a legal argument against someone who releases embarrassing secrets.

Barack Obama’s Attorney General, Eric Holder, said as far back as 2010 the WikiLeaks founder was the focus of an “active, ongoing criminal investigation.” Assange at the time had won, or was en route to winning, a pile of journalism prizes for releasing embarrassing classified information about many governments, including the infamous “Collateral Murder” video delivered by Chelsea Manning. The video showed a helicopter attack in Iraq which among other things resulted in the deaths of two Reuters reporters.

Last year, we reported a rumored American criminal case against Assange was not expected to have anything to do with 2016, Russians, or DNC emails. This turned out to be the case, as the exact charge is for conspiracy, with Chelsea Manning, to hack into a “classified U.S. government computer.”

The indictment unveiled today falls just short of a full frontal attack on press freedoms only because it indicts on something like a technicality: specifically, an accusation that Assange tried (and, seemingly, failed) to help Manning crack a government password.

For this reason, the language of the indictment underwhelmed some legal experts who had expressed concerns about the speech ramifications of this case before.

“There’s a gray area here,” says University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck. “But the government at least tries to put this at the far end of the gray area.”

Not everyone agreed. Assange lawyer Barry Pollock said the allegations “boil down to encouraging a source to provide him information and taking efforts to protect the identify of that source.”

“The weakness of the US charge against Assange is shocking,” tweeted Edward Snowden. “The allegation he tried (and failed?) to help crack a password during their world-famous reporting has been public for nearly a decade: it is the count Obama’s DOJ refused to charge, saying it endangered journalism.”

Part of the case clearly describes conduct that exists outside the normal parameters of press-source interaction, specifically the password issue. However, the evidence about this part of the conspiracy seems thin, limited mainly to Assange saying he’d had “no luck so far,” apparently in relation to attempts to crack the password.

The meatier parts of the indictment speak more to normal journalistic practices. In its press release, the Justice Department noted Assange was “actively encouraging Manning” to provide more classified information. In the indictment itself, the government noted Assange told Manning, who said she had no more secrets to divulge, “curious eyes never run dry.”

Also in the indictment:

“It is part of the conspiracy that Assange and Manning took measures to conceal Manning as the source of the disclosure.”

Reporters have extremely complicated relationships with sources, especially whistleblower types like Manning, who are often under extreme stress and emotionally vulnerable.

At different times, you might counsel the same person both for and against disclosure. It’s proper to work through all the reasons for action in any direction, including weighing the public’s interest, the effect on the source’s conscience and mental health, and personal and professional consequences.

For this reason, placing criminal penalties on a prosecutor’s interpretation of such interactions will likely put a scare into anyone involved with national security reporting going forward.

As Ben Wizner of the ACLU put it:

“Any prosecution by the United States of Mr. Assange for WikiLeaks’ publishing operations would be unprecedented and unconstitutional, and would open the door to criminal investigations of other news organizations.”

Unfortunately, Assange’s case, and the very serious issues it raises, will be impacted in profound ways by things that took place long after the alleged offenses, specifically the Russiagate story. It’s why some reporters are less than concerned about the Assange case today.

About that other thing, i.e. Assange’s role in the 2016 election:

Not only did this case have nothing to do with Russiagate, but in one of the odder unreported details of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, he never interviewed or attempted to interview Assange. In fact, it appears none of the 2800 subpoenas, 500 witness interviews, and 500 search warrants in the Mueller probe targeted Assange or WikiLeaks.

According to WikiLeaks, no one from Mueller’s office ever attempted to get a statement from Assange, any WikiLeaks employee, or any of Assange’s lawyers (the Office of Special Counsel declined comment for this story). A Senate committee did reach out to Assange last year about the possibility of testifying, but never followed up.

As Pollock told me in February,

“[Assange] has not been contacted by the OSC or the House.” There was a Senate inquiry, he said, but “it was only an exploratory conversation and has not resulted in any agreement for Mr. Assange to be interviewed.”

Throughout the winter I asked officials and former prosecutors why officials wouldn’t be interested in at least getting a statement from a person ostensibly at the center of an all-consuming international controversy. There were many explanations offered, the least curious being that Assange’s earlier charges, assuming they existed, could pose legal and procedural obstacles.

Now that Assange’s extant case has finally been made public, the concern on that score “dissipates,” as one legal expert put it today.

It will therefore be interesting to see if Assange is finally asked about Russiagate by someone in American officialdom. If he isn’t, that will be yet another curious detail in a case that gets stranger by the minute.

As for Assange’s case, coverage by a national press corps that embraced him at the time of these offenses — and widely re-reported his leaks — will likely focus on the narrow hacking issue, as if this is not really about curtailing legitimate journalism.

In reality, it would be hard to find a more extreme example of how deep the bipartisan consensus runs on expanding the policing of leaks.

Donald Trump, infamously and ridiculously, is a pronounced Twitter fan of WikiLeaks, even comparing it favorably to the “dishonest media.” His Justice Department’s prosecution of Assange seems as counter-intuitive as the constitutional lawyer Barack Obama’s expansion of drone assassination programs.

Both things happened, though, and we should stop being surprised by them — even when Donald Trump takes the last step of journey begun by Barack Obama.

____________________________________________

Matt Taibbi is a contributing editor for Rolling Stone. He’s the author of five books and a winner of the National Magazine Award for commentary. Please direct all media requests to taibbimedia@yahoo.com.

Matt Taibbi is a contributing editor for Rolling Stone. He’s the author of five books and a winner of the National Magazine Award for commentary. Please direct all media requests to taibbimedia@yahoo.com.

Go to Original – rollingstone.com

Tags: Activism, Assange, Big Brother, Democracy, Edward Snowden, Journalism, Media, Military, NATO, Nonviolence, Surveillance, UK, USA, Violence, War, Whistleblowing, WikiLeaks

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.