Bridging the Gap between Strategic and Principled Nonviolence

REVIEWS, 24 Jun 2019

Markus Bayer | Waging Nonviolence – TRANSCEND Media Service

Stellan Vinthagen’s 2015 book “A Theory of Nonviolent Action” develops a new theoretical framework for what nonviolence is.

29 May 2019 – For over 40 years Gene Sharp’s seminal work “The politics of Nonviolent Action” has built the theoretical basis for nonviolent action and civil resistance scholars. Four years ago, in 2015, Stellan Vinthagen published A Theory of Nonviolent Action: How Civil Resistance Works with the aim to “develop a conceptual framework and a new theoretical framework of what ‘nonviolence’ is.” However, it seems that the book has not received the attention it deserves so far. To change this, I will discuss the main arguments of Vintagen’s book in a teaser-like review; the book is actually too rich to fully cover it in short.

The author Stellan Vinthagen is one of the key figures within the community of resistance studies. He is founder of the Resistance Studies Network, editor of the Journal of Resistance Studies and, last but not least, owner of the Inaugural Endowed Chair in the Study of Nonviolent Direct Action and Civil Resistance at the University of Massachusetts. Considering Vinthagen’s solid background as an activist on the one hand and as a well-read sociologist on the other, the book promises a lot.

Vinthagen’s overall goal laid down in the introduction is to develop a “sociological perspective to interpret and conceptually describe nonviolent moments in conflict situation.” Therefore, he starts with the ‘forefathers’ of nonviolence, Gandhi and Sharp.

The first chapter, “nonviolent action studies,” is a commented review of literature on the topic, where Vinthagen summarizes and criticises the rival approaches of Gandhi and Sharp completed by some illustrative historical examples. He tries to ground Gandhi’s “theology of liberation“ on sociological theoretical grounds rather than on religious and moral motives and criticizes Sharp’s approach to nonviolence as “problematically reductionist” theory of power. However, he relies his theory on Sharp’s strategic approach and develops it further by including critiques of the cultural turn. In doing so, Vinthagen returns to the sources of Gandhi and establishes as synthesis a third position where he describes nonviolence as social pragmatism “beyond moral high priests of nonviolence and anti-moral strategy generals.”

This very ambitious claim aims to bridge the decades-old chasm between strategic on the one hand and principled nonviolence on the other hand or, in other words, between ‘Gandhians’ and ‘Sharpians’. This third position advanced here is based on the assumption that every social group has a normative structure so that, consequently, even the purest form of pragmatism is driven by norms, in this case, the norm of goal rationality. In turn, principled nonviolence follows the goal of norm conformity and norm rationality. In this sense, pragmatism and principled motivations can be understood as expressions of different forms of rationality and not as antagonism.

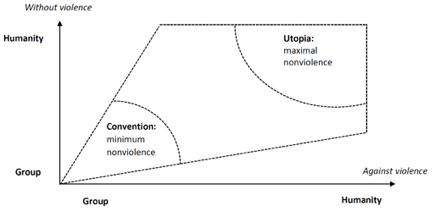

After this reasoning, Vinthagen comes to a definition of the term nonviolence. Contrary to most one-dimensional definitions that focus only on the means and neglect the goal, Vinthagen here follows Gandhi and propagates the unity of ends and means and brings nonviolence to the formula of “without violence + against violence.” According to Vinthagen, nonviolent action furthermore displays the following characteristics: Norm violation, vulnerability and normalization. This means, in short, that nonviolent action breaches norms in order to normalize a new behaviour and to establish new norms, even at the risk of exposing oneself to violence. Furthermore, Vinthagen introduces the idea of truth seeking, suffering, and a constructive program, an element that can also be found in the philosophy of Gandhi, and which will play a crucial role in his own approach.

The second chapter departs from the definition of nonviolence as “without violence + against violence” and elaborates the concept of nonviolence as an antidote to violence. According to Vinthagen, two aspects have to be considered here: the fact that there are different definitions of violence ranging from physical to structural and cultural violence, and the question to whom nonviolence applies (the own in-group, the own nation, all human beings etc.).

Vinthagen understands nonviolence as universal, meaning that both the group of people concerned and the definition of violence have to be broadly understood. As, in reality, groups tend to set their group-boundaries and their definition of violence differently, these boundaries and definitions have to be widened constantly.

Thereby, constant nonviolent ‘work’ is essential meaning that “the construction of social structures, institutions and practices, that replace those being fought against” become a core concern for nonviolent movements.

In theory-laden chapter three, Vinthagen introduces the idea of nonviolence as a multi-rational action in conflicts. Vinthagen emanates from Habermas’ idea that human action follows four different kinds of rationalities: Goal rationality (if a certain action is undertaken because it works), dramaturgical (if it is undertaken to expresses something aesthetic or a symbolic meaning that goes beyond the action), communicative (if it is oriented towards an understanding or towards an agreement) and norm regulated rationality (if guided by group’s norms, institutions or morals).

In contrast to Sharp, who perceives nonviolent action only as a strategic, goal-rational action, Vinthagen perceives it as multi-rational action following different rationalities at the same time. Thereby, each type of action has its own potential to contribute to social change – or, in other words, to make nonviolence work: Following a communicative logic, nonviolent action can facilitate dialogue with the “enemy” (see chapter four). In its goal rational dimension nonviolent action has the potential to break given power structures (see chapter five). In its dramaturgical logic, it can “enact” utopian visions (chapter six). Last but not least, in its norm regulated dimension it has the power to contest norms and to claim and uphold new ones (chapter seven).

The following chapters each describe in detail one of the dimensions of nonviolence and its underlying rationality.

Chapter 4: Truth-seeking and dialogue facilitation

In this chapter, Vinthagen introduces what he calls the communicative rationality of nonviolence and its dimension of dialogue facilitation. Therefore, he brings together Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha and Habermas’ theory of communicative action. He argues that both share the belief in the existence of a mutual truth. While Gandhi’s truth is absolute, Habermas follows the idea that one can find a commonplace through deliberation. In both concepts, the “opponent” is the essential element to come closer to the absolute truth or to reach a higher level of communicative rationality.

Furthermore, both approaches claim that violence such as the killing of a person makes a dialogue impossible and thus prevents from gaining a deeper understanding of the ‘truth’. Importantly, Vinthagen understands the ‘ideal speech situation’ as utopian ideal, which is nevertheless meaningful to constantly widen the real sphere of dialogue facilitation. In this sense, Vinthagen states that “Habermas’ ‘ideal speech situation’ presupposes Gandhi’s ‘nonviolent resistance’ in order to be meaningful in a world characterized by power and violence” (160), which leads us to the next chapter “power breaking”.

Chapter 5: Power breaking

In chapter five Vinthagen introduces the goal-rationality and the power breaking dimension of nonviolence. Since this is the most studied dimension of nonviolence, the chapter mainly reviews and criticises Sharp’s strategic approach and its consent theory of power. As Vinthagen rightly states, Sharp’s approach to power ignores nearly all theoretical innovations that have been brought in by the cultural turn. Following Foucault, he argues that power affects the individual in softer and more structural forms (e.g. via culture, structures of knowledge and by habitus) than Sharp’s simple relation of command and obedience.

Accordingly, Vinthagen states that „[n]ot even the will, body and mind of the resistance fighter is free from power.” While highlighting this important structural dimension of power, Vinthagen points as well to the aspect of agency in stating that “even if power is everywhere, it is not everything” and it is “not total.” In this sense, he states that resistance or “obedience (like all human acts) implies choice.” Nonviolent resistance, as a goal-rational action, has proven to being able to break power relations and bring even more powerful enemies to the negotiation table.

Chapter 6: Utopian enactment

In this chapter Vinthagen develops the innovative dimension of what he calls “utopian enactment”. Once again Vinthagen keeps his straight sociological perspective and draws from Mead’s and Goffman’s symbolic interactionism to explain the self-expressive and dramaturgical rationality of nonviolence. According to Vinthagen “[u]topian enactment is focused on an individual’s relationship to the other, the opponent, and it attempts to counter prevailing images, emotional predispositions and attitudes towards the activist.”

This means that a refrain from violence and dialogue facilitation opens up and uphold channels of communication to start a discourse. Furthermore, and that is the utopian aspect, nonviolence can be an “as if” action in the sense that it can embody an attractive possibility of living together in respect and mutuality. The idea is that the action of the resistors already mirrors the goals. Thereby the dual aspect of nonviolence – refraining from violence and “self-suffering” – plays a key role since it helps to make this utopian vision mutually attractive and at the same time expresses authenticity and commitment of the activists.

Chapter 7: Normative regulation

Departing from the observation that we live in a world where violence is hegemonic, Vinthagen introduces normative regulation as a concept to overcome this hegemony of violence. Similar to Gandhi, who argues that we do not build the new society out of the ashes of the old but have to develop a “constructive program” to establish alternative institutions, norms, and practices in parallel to acts of resistance, Vinthagen argues that we have to “normalize” nonviolence.

In his conception nonviolent training becomes a cornerstone to internalise nonviolence until it becomes a part of one’s routine practices or one’s own habitus. However, Vinthagen has to admit that normative regulation also includes sanctions so that “[e]ven if a nonviolent community tries to apply less violent sanctions […] [it] might still feel violent to those affected.”

The book’s eighth chapter brings together the previous paragraphs and merges the different theoretical aspects into “A theory of nonviolent action”. For readers who are in a hurry or for readers who are familiar with current debates of nonviolence and the sociological concepts described, this chapter can be read separately from the others.

After having sketched out the contents, I want to critically discuss the book in pointing particularly at three problems that I see in Vinthagen’s theory on nonviolence:

The problem of widening and upholding the consensus of nonviolence

The question how to transform in time and space fragmented nonviolent movements into more persistent and global units and phases of nonviolence is a pressing one. As a reader, I therefore cannot thank the author enough for daring to take up this mostly unexplored field. However, that does not mean that the topic is not controversial.

Although it is not empirically self-evident, we can easily imagine a relatively small social entity like a family following a very maximalist definition of nonviolence. Furthermore, we can imagine that most cultures on earth share the same basic normative consensus that killing others is not the preferred way of living together. However, widening the group of people concerned and the definition of violence at the same time poses some fundamental problems: We have to prioritize in one way or another. Furthermore, what can we do to “defend” the achieved level of nonviolence and to advance it further? Which level of violence is acceptable to prevent people from deviating from the nonviolent consensus?

The current system of national states could be seen as one form of compromise. According to social contract philosophers like Rousseau the national state promises the pacification of the people living within its borders by the establishment of the monopoly of violence and the rule of law. The group of people concerned is the nation; the definition of violence is more or less physical violence. State organs like the police enforce the monopoly of violence and the rule of law by using limited violence. The people accept these measures as a smaller evil to avoid the danger of physical violence via the imagined social contract.

Theoretically, however, the problem is that new members of the community have never signed this contract and have to submit themselves under the existing rules. Furthermore, a given state of nonviolence will probably set in motion a logic to defend it: The more valuable an asset, the more are people ready to accept all necessary means including violence to defend it. This furthermore makes it difficult to widen the group of people concerned as newcomers can be perceived as potential threat to the existing order. The current attempts to limit migration to Europe and the US somehow reflect this problem.

The problem of normative regulation

Normative regulation is Vinthagen’s response to the above-mentioned problem of upholding nonviolent consensus, especially under the premise of constant widening.

Normative regulation can maybe best be compared with a police force. While the latter is legitimized to use physical force to enforce the laws and ultimately to prevent more violence, the first uses nonviolent sanctions and, as last resort, exclusion from the movement to uphold the “consensus”. The comparison between both, the police and normative regulation in movements, discloses that normative regulation works on a lower level of violence, but mostly within a smaller group of people concerned. Normative regulation, however, also includes violence at least in a wider sense. If nonviolence means “without violence and against violence” and the normative goal of nonviolence is to widen the group of persons concerned (from family members and close friends to a whole society of the world population) as well as the definition of violence (from direct physical to structural and cultural violence), sanctioning deviant behaviour seems contradictory.

In a purely nonviolent thinking, the group can only be widened by convincing people to submit themselves voluntarily under the rules they choose to obey. This is not about demanding anarchy (without authority) but autonomia (in the sense of self-legislation). If there is nothing but the free submission under self-given rules and, at the same time, the group of people concerned is widened, the potential risk of non-conform behaviour rises. Every step to control the norms and to create institutions to defend them against non-conformists, however, would be a step in the direction of the established state system.

Vinthagen states that the hegemony of violence must be replaced by a hegemony of nonviolence. Therefore, nonviolence needs to be incorporated into the habitus of the people. However, neither hegemony nor habitus are concepts build on agency or the free choice of the people, but belong to more structuralist theories that emphasize limited choices and persistence of power. It therefore seems contradictory that the key to a reduction of submission should lie in a renewed submission. In other words: If the hegemony of power is replaced by a hegemony of nonviolence, it still is a hegemony. If nonviolence becomes incorporated in our habitus, it isn’t longer a free choice. If it isn’t a free and conscious choice, it is unconscious submission.

Clear-cut sociological perspective at the cost of interdisciplinarity

Vinthagen originally intended to name the book “sociology of nonviolence”, which would have been, in my eyes, the more fitting title since it is a straight sociological take on the phenomenon of nonviolence. Furthermore, the original title would have been a call for interdisciplinary complementation. In this sense, the actual title is a little bit misleading as it does not include additional perspectives on nonviolence, all foremost a psychological one. Proposing a sociology of nonviolence, Vinthagen criticises Sharp for his focus on agency and his neglect of structural (cultural) constraints of the free will.

He nevertheless follows the assumption that nonviolence is a choice of the actor, however limited. Thus, he assumes that we have to change existing normative standards and establish a culture of nonviolence across the globe. In following a uniquely sociologist approach, Vinthagen is taken in by a general weakness of the sociological literature on nonviolent resistance, namely its neglect of other explanations of violent behaviour as, for example, aggression. If violent behaviour is not only a matter of choice and outcome of established normative orders and practical training, but influenced by psychological factors, how then do we tackle aggressive behaviour? To advance the field further, a stronger interdisciplinary collaboration with other fields like psychology is very urgent. Sadly, however, up to now psychological studies on nonviolence only played a marginal role (Gregg, Pelton and Moyton are the rare exceptions).

Stellan Vinthagen’s “Theory of Nonviolent Action” is definitively the most important theoretical contribution to the field of nonviolent action and resistance studies since Gene Sharp laid the theoretical groundworks in 1973. In my eyes the conceptualization of nonviolent action as a multi-rational action in conflict is convincing and well-grounded in sociological theory.

Furthermore, the framework has indeed the potential to reach the ambitious goal of reconciling the two camps of Gandhians and Sharpians. Last but not least, the dimensions of dialogue facilitation, utopian enactment and normative regulation open up new barely covered fields for research and, at the same time, offer some important theoretical guidance for it.

As the criticism mentioned above shows, the book cannot answer all questions, but it provides an excellent, theoretically rich starting point to deepen the theoretical debate on nonviolence or to expand theorizing to related fields and disciplines. I would recommend the book for every student and scholar who is familiar with the actual debates within nonviolent resistance studies. Due to its demanding theory, it is, however, not very suitable for those who want a short and easy introduction.

___________________________________________________

Markus Bayer is a Political Scientist and Ph.D. student at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany. He is currently working on a project on “Nonviolent Resistance and Democratic Consolidation”, which is closely related to his doctoral research. His main research interests are peace and conflict studies, nonviolent resistance, democratization, and social movements. His latest publications include articles on “The Democratic Dividend of Non-Violent Resistance” (OA in Journal of Peace Research) and “Heroes and Victims: Economies of Entitlement after violent Pasts” (in Peacebuilding).

Go to Original – wagingnonviolence.org

Tags: Activism, Conflict, Literature, Nonviolence, Politics, Power, Reviews, Social justice, Solutions

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.