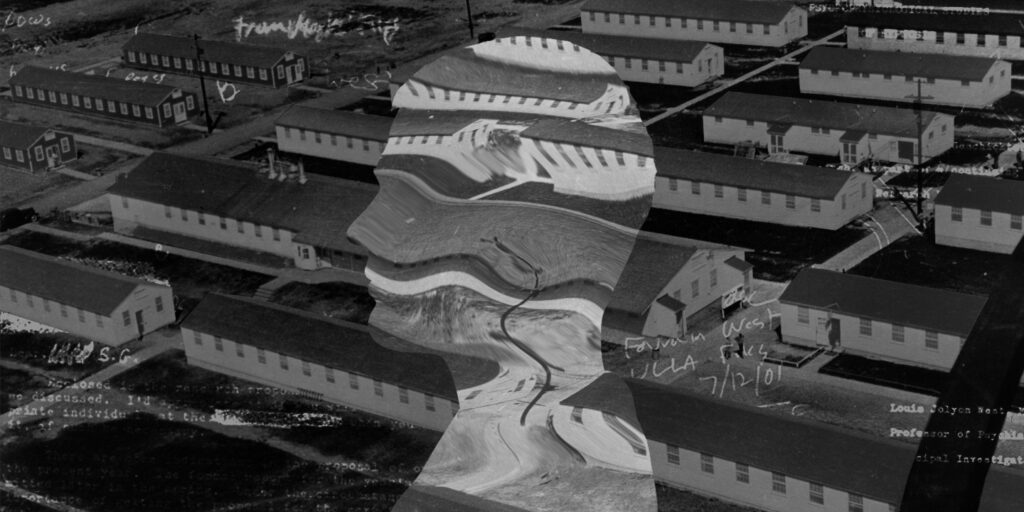

Inside the Archive of an LSD Researcher with Ties to the CIA’s MKUltra Mind Control Project

ANGLO AMERICA, 2 Dec 2019

Tom O’Neill and Dan Piepenbring – The Intercept

24 Nov 2019 – On the night of July 4, 1954, San Antonio, Texas, was shaken by the rape and murder of a 3-year-old girl. The man accused of these crimes was Jimmy Shaver, an airman at the nearby Lackland Air Force Base with no criminal record. Shaver claimed to have lost his memory of the incident.

The victim, 3-year-old Chere Jo Horton, had disappeared around midnight outside the Air Force Base, where her parents had left her in the parking lot outside a bar; she played with her brother while they had a drink inside. When they noticed her missing, they formed a search party.

Within an hour, the group came upon a car parked next to a gravel pit; Chere’s underwear was hanging from one of the car’s doors. Shaver wandered out of the darkness. He was shirtless, covered in blood and scratches. Making no attempt to escape, he let the search party walk him to the edge of the highway. Bystanders described him as “dazed” and in a “trance-like” state.

“What’s going on here?” he asked. He didn’t seem drunk, but he couldn’t say where he was, how’d he gotten there, or whose blood was all over him. Meanwhile, the search party found Horton’s body in the gravel pit. Her neck was broken, her legs had been torn open, and she’d been raped.

Deputies arrested Shaver. At 29, he was recently remarried with two children and no history of violence. He’d been at the same bar Horton had been abducted from, but he’d left with a friend, who told police that neither of them was drunk, though Shaver had seemed high on something. Before deputies could take Shaver to the county jail, a constable from another precinct arrived with orders from military police to assume custody of him.

Around four that morning, an air force marshal questioned Shaver and two doctors examined him, agreeing he wasn’t drunk. One later testified that he “probably was not normal … he was very composed outside, which I did not expect him to be under these circumstances.” He was released to the county jail and booked for rape and murder.

Investigators interrogated Shaver through the morning. When his wife came to visit, he didn’t recognize her. He gave his first statement at 10:30 a.m., adamant that another man was responsible: He could summon an image of a stranger with blond hair and tattoos. After the air force marshal returned to the jailhouse, however, Shaver signed a second statement taking full responsibility. Though he still didn’t remember anything, he reasoned, he must have done it.

Two months later, in September, Shaver’s memories still hadn’t returned. The commander of the base hospital, Col. Robert S. Bray, ordered a psychiatric evaluation, to be performed by Dr. Louis Jolyon West, the head of psychiatric services at the air base. It fell to West to decide if Shaver had been legally sane at the time of the murder.

Shaver spent the next two weeks under West’s supervision. They returned to the scene of the crime, trying to jog his memory. Later, West hypnotized Shaver and gave him an injection of sodium pentothal, or “truth serum,” to see if he could clear his amnesia.

While Shaver was under, according to testimony, he recalled the events of that night. He confessed to killing Horton. She’d brought out repressed memories of his cousin, “Beth Rainboat,” who’d sexually abused him as a child. Shaver had started drinking at home that night when he “had visions of God, who whispered into his ear to seek out and kill the evil girl Beth.”

While Shaver was under hypnosis, he confessed to killing the young girl. At trial, he maintained his innocence.

At the trial, West made only a minimal effort to exonerate Shaver. The airman was found guilty. Though an appeals court later ruled that he’d had an unfair trial, he was convicted again in the retrial. In 1958, on his 33rd birthday, he was executed by the electric chair. He maintained his innocence the whole time.

The trial, which hinged on Shaver’s testimony, might have ended differently had the jury known about West’s past. According to newly surfaced papers from West’s archives, the psychiatrist had some of the clearest, most nefarious ties of any scientist to the CIA’s Project MKUltra. West’s files — especially his correspondence with the CIA’s longtime poisons expert, Sidney Gottlieb — shed new light on one of the most infamous projects in the agency’s history. Likely comprising more than 149 subprojects and at least 185 researchers working at institutions across America and Canada, MKUltra was, as the New York Times put it, “a secret twenty-five year, twenty-five million dollar effort by the CIA to learn how to control the human mind.” Its experiments violated international laws, not to mention the agency’s charter, which forbids domestic activity.

At the trial, West maintained that Shaver had suffered a bout of temporary insanity on the night of Chere Jo Horton’s killing, but he argued that Shaver was “quite sane now.” In the courtroom, Shaver didn’t look that way. One newspaper account said he “sat through the strenuous sessions like a man in a trance,” saying nothing, never rising to stretch or smoke, though he was a known chain-smoker.

Large portions of West’s truth serum interview with Shaver were read into the court record. The doctor had used leading questions to walk the entranced Shaver through the crime. “Tell me about when you took your clothes off, Jimmy,” he’d said. The transcript of the interview, which survived among West’s papers, also showed West trying to prove that Shaver had repressed memories: “Jimmy, do you remember when something like this happened before?” Or: “After you took her clothes off, what did you do?”

“I never did take her clothes off,” Shaver said.

The interview was divided into thirds, and the middle third hadn’t been recorded. When the transcript picked up, it said: “Shaver is crying. He has been confronted with all the facts repeatedly.”

West asked, “Now you remember it all, don’t you, Jimmy?”

“Yes, sir,” Shaver replied.

Though lawyers scrutinized Shaver’s medical history, little mention was made of the base hospital where West’s archived letters indicate he had conducted his MKUltra experiments. Shaver had suffered from migraines so debilitating that he’d dunk his head in a bucket of ice water when he felt one coming on. His condition was severe enough that the Air Force had recommended him for a two-year experimental program. The doctor who’d attempted to recruit him was not named in court records or transcripts.

On the stand, West said he’d never gotten around to seeing whether Shaver had been treated in the experimental program. Lackland officials told me there was no record of him in their master index of patients. But, curiously, according to the base’s archivist, all the records for patients in 1954 had been maintained, with one exception: the file for last names beginning with “Sa” through “St” had vanished.

Dr. Louis Jolyon West in San Francisco, Calif., in 1976.

Photo: Lawrence Schiller/Polaris Communications/Getty Images

West’s professional fascination with LSD was practically as old as the drug itself. For several decades, he was one of an elite cadre of scientists using it in top-secret research. Lysergic acid diethylamide was synthesized in 1938 by chemists at Switzerland’s Sandoz Industries, but it was not introduced as a pharmaceutical until 1947. In the fifties, when the CIA began to experiment on humans with it, it was a new substance. Albert Hofmann, the Swiss scientist who’d discovered its hallucinogenic qualities in 1943, described it as a “sacred drug” that gestured toward “the mystical experience of a deeper, comprehensive reality.”

In the ’50s, even before hippies embraced the drug, “Very few people took LSD without having somebody being a ‘trip leader,’” Charles Fischer, a drug researcher, told me. The suggestibility from LSD was akin to that associated with hypnosis; West had studied the two in tandem. “You can tell somebody to hurt somebody, but you call it something else,” Fischer explained. “Hammer the nail into the wood, and the wood, perhaps, is a human being.”

West seems to have used chemicals liberally in his medical practice, and his tactics left an indelible mark on the psychiatrists who worked with him. One of them, Gilbert Rose, was so baffled by the Shaver case that he went on to write a play about it.

“In my 50 years in the profession, that was the most dramatic moment ever — when he clapped his hands to his face and remembered killing the girl,” Rose said in 2002 of Shaver and the truth serum interview. But Rose was shocked when I told him that West had hypnotized Shaver in addition to giving him sodium pentothal. Hypnotism, he said, was not part of the protocol for the interview.

He’d also never known how West had found out about the case right away.

“We were involved from the first day,” Rose recalled. “Jolly phoned me the morning of the murder. He initiated it.”

West claimed he was in the courtroom the day Shaver was sentenced to death. Around this time, he became vehemently opposed to capital punishment. Did he know his experiments might’ve led to the execution of an innocent man and the death of a child? If his correspondence with CIA head of MKUltra Gottlieb — predating the crime by just a year — had been presented at trial, would the outcome have been the same?

Almost as soon as they had access to it, government scientists saw LSD as a potential Cold War miracle drug. Full-fledged U.S. research into LSD began soon after the end of World War II, when American intelligence learned that the USSR was developing a program to influence human behavior through drugs and hypnosis. The United States believed that Soviets could extract information from people without their knowledge, program them to make false confessions, and perhaps persuade them to kill on command.

In 1949, the CIA, then in its infancy, launched Project Bluebird, a mind-control program that tested drugs on American citizens — most in federal penitentiaries or on military bases — who didn’t even know about, let alone consent to, the battery of procedures they underwent.

Their abuse found further justification in 1952, when, in Korea, captured American pilots admitted on national radio that they’d sprayed the Korean countryside with illegal biological weapons. It was a confession so beyond the pale that the CIA blamed communists: The POWs must have been “brainwashed.” The word, a literal translation of the Chinese “xi nao,” didn’t appear in English before 1950. It articulated a set of fears that had coalesced in postwar America: that a new class of chemicals could rewire and automate the human mind.

“You can tell somebody to hurt somebody, but you call it something else,” Fischer explained. “Hammer the nail into the wood, and the wood, perhaps, is a human being.”

When the American POWs returned, the Army brought in a team of scientists to “deprogram” them. Among those scientists was West. Born in Brooklyn in 1924, he had enlisted in the Air Force during World War II, eventually rising to the rank of colonel. His friends called him “Jolly,” for his middle name, impressive girth, and oversized personality. When he got out, he researched methods of controlling human behavior at Cornell University. He would later claim to have studied 83 prisoners of war, 56 of whom had been forced to make false confessions. He and his colleagues were credited with reintegrating the POWs into Western society and, maybe more important, getting them to renounce their claims about having used biological weapons.

West’s success with the POWs gained him entrance into the upper echelons of the intelligence community. Gottlieb, the poisons expert who headed the chemical division of the CIA’s Technical Services Staff, along with Richard Helms, the CIA’s chief of operations for the Directorate of Plans had convinced the agency’s then-director, Allen Dulles, that mind control ops were the future. Initially, the agency wanted only to prevent further potential brainwashing by the Soviets. But the defensive program became an offensive one. Operation Bluebird morphed into Operation Artichoke, a search for an all-purpose truth serum.

In a speech at Princeton University, Dulles warned that communist spies could turn the American mind into “a phonograph playing a disc put on its spindle by an outside genius.” Just days after those remarks, on April 13, 1953, he officially set Project MKUltra in motion.

Little is known about the program. After Watergate, Helms (who by that time was CIA director) ordered Gottlieb to destroy all MKUltra papers; in January 1973, the Technical Services staff shredded countless documents describing the use of hallucinogens.

In the mid-1970s, after the Times revealed the existence of MKUltra on its front page, the government launched three separate investigations, all of which were hobbled by the CIA’s destruction of its files: Vice President Nelson Rockefeller’s Commission on CIA Activities within the United States (1975); Senator Frank Church’s Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (1975-6); and Senators Edward Kennedy and Daniel Inouye’s joint Senate Select Committee hearings on Project MKUltra, the CIA’s Program of Research in Behavioral Modification (1977). When records were available, they were redacted; when witnesses were summoned to testify before Congress, they were forgetful.

We do know the project’s broadest goal was “to influence human behavior.” Under its umbrella were at least 149 subprojects, many involving research on unwitting participants. Gottlieb, whose aptitude and amorality earned him the nickname the “Black Sorcerer,” developed gadgetry straight out of schlocky sci-fi: high-potency stink bombs, swizzle sticks laced with drugs, exploding seashells, poisoned toothpaste. Having persuaded an Indianapolis pharmaceutical company to replicate the Swiss formula for LSD, the CIA had a limitless domestic supply of its favorite new drug. The agency hoped to produce couriers who could embed hidden messages in their brains, to implant false memories and remove true ones in people without their awareness, to convert groups to opposing ideologies, and more. The loftiest objective was the creation of hypno-programmed assassins.

The most sensitive work was conducted far from Langley — farmed out to scientists at colleges, hospitals, prisons, and military bases all over the United States and Canada. The CIA gave these scientists aliases, funneled money to them, and instructed them on how to conceal their research from prying eyes, including those of their unknowing subjects.

Their work encompassed everything from electronic brain stimulation to sensory deprivation to “induced pain” and “psychosis.” They sought ways to cause heart attacks, severe twitching, and intense cluster headaches. If drugs didn’t do the trick, they’d try to master ESP, ultrasonic vibrations, and radiation poisoning. One project tried to harness the power of magnetic fields.

MKUltra was so highly classified that when John McCone succeeded Dulles as CIA director late in 1961, he was not informed of its existence until 1963. Fewer than half a dozen agency brass were aware of it at any period during its 20-year history.

West headed the psychiatry department at UCLA and the school’s renowned neuroscience center until his retirement in 1988. One day, among a batch of research papers on hypnosis in West’s archives there, I found letters between West and his CIA handler, “Sherman Grifford” — the cover name, according to John Marks’s “The Search for the Manchurian Candidate,” for Sidney Gottlieb. West, who had once written to a magazine editor that he had “never worked for the CIA,” had in fact worked closely with the agency’s “Black Sorcerer” himself.

The letters picked up midstream, with no prologue or preliminaries. The first was dated June 11, 1953, a mere two months after MKUltra started, when West was chief of the psychiatric service at the air base at Lackland.

Who would the guinea pigs be? West listed four groups: basic airmen, volunteers, patients, and “others, possibly including prisoners in the local stockade.”

Addressing Gottlieb as “S.G.,” West outlined the experiments he proposed to perform using a combination of psychotropic drugs and hypnosis. He began with a plan to discover “the degree to which information can be extracted from presumably unwilling subjects (through hypnosis alone or in combination with certain drugs), possibly with subsequent amnesia for the interrogation and/or alteration of the subject’s recollection of the information he formerly knew.” Another item proposed honing “techniques for implanting false information into particular subjects … or for inducing in them specific mental disorders.” He hoped to create “couriers” who would carry “a long and complex message” embedded secretly in their minds, and to study “the induction of trance-states by drugs.” His list lined up perfectly with the goals of MKUltra.

“Needless to say,” West added, the experiments “must eventually be put to test in practical trials in the field.” To this end, he asked Gottlieb for “some sort of carte blanche.”

Who would the guinea pigs be? He listed four groups: basic airmen, volunteers, patients, and “others, possibly including prisoners in the local stockade.” Only the volunteers would be paid. The others could be unwilling, and, though it wasn’t spelled out, unwitting. It would be easier to preserve his secrecy if he were “inducing specific mental disorders” in people who already exhibited them. “Certain patients requiring hypnosis in therapy, or suffering from dissociative disorders (trances, fugues, amnesias, etc.) might lend themselves to our experiments.” Official investigations into MKUltra yielded little information about its subjects, but West’s letter suggests that the program cast a wide net.

Gottlieb’s reply came on letterhead from “Chemrophyl Associates,” a front company he used to correspond with MKUltra subcontractors. “My Good Friend,” he wrote, “I had been wondering whether your apparent rapid and comprehensive grasp of our problems could possibly be real. … you have indeed developed an admirably accurate picture of exactly what we are after. For this I am deeply grateful.”

Gottlieb saluted his new recruit: “We have gained quite an asset in the relationship we are developing with you.”

West returned the camaraderie: “It makes me very happy to realize that you consider me ‘an asset,’” he replied. “Surely there is no more vital undertaking conceivable in these times.”

In 1954, around the same time as Chere Jo Horton’s murder, West began to split his time between Lackland and the University of Oklahoma School of Medicine, where he would lead the psychiatry department.

West had told his prospective employer that his Lackland duties were “purely clinical” and that he’d “been doing no research, classified or otherwise” — and he asked the board of directors at Oklahoma for permission to accept money from the Geschickter Fund for Medical Research, which he called “a non-profit private research foundation.” In fact, as the CIA later acknowledged, Geschickter was another of Gottlieb’s fictions, a shell organization enabling him.

In 1956, West reported back to the CIA that the experiments he’d begun in 1953 had at last come to fruition. In a 1956 paper titled “The Psychophysiological Studies of Hypnosis and Suggestibility,” he claimed to have achieved the impossible: He knew how to replace “true memories” with “false ones” in human beings without their knowledge. Without detailing specific incidents, he put it in layman’s terms: “It has been found to be feasible to take the memory of a definite event in the life of an individual and, through hypnotic suggestion, bring about the subsequent conscious recall to the effect that this event never actually took place, but that a different (fictional) event actually did occur.” He’d done it, he claimed, by administering “new drugs” effective in “speeding the induction of the hypnotic state and in deepening the trance that can be produced in given subjects.”

At the National Security Archives in D.C., I found the version of “The Psychophysiological Studies of Hypnosis and Suggestibility” that the CIA turned over to Senators Kennedy and Inouye in 1977. West’s name and affiliation were redacted, as expected. But the CIA’s version was also shorter, and watered down in comparison. West’s document was 14 pages. This one was five, including a cover page. Most glaringly, there was no mention of West’s triumphant accomplishment, the replacement of “the memory of a definite event in the life of an individual” with a “fictional event.”

One passage, not in West’s original, claims the CIA never used LSD in studies at all: “The effects of [LSD and other drugs] upon the production, maintenance, and manifestations of disassociated states has never been studied.”

West, of course, had studied those effects for years. But when it came to elaborating on his findings about implanting memories and controlling thoughts, even in the paper found in West’s own files, he offered few details. He seems to have been in a rudimentary phase of his research. Acid, he wrote, made people more difficult to hypnotize; it was better to pair hypnosis with long bouts of isolation and sleep deprivation. Using hypnotic suggestion, he claimed, “a person can be told that it is now a year later and during the course of this year many changes have taken place…so that it is now acceptable for him to discuss matters that he previously felt he should not discuss…An individual who insists he desires to do one thing will reveal that secretly he wishes just the opposite.”

Had the CIA doctored West’s original document to mislead the Senate committee? And if so, why would the agency have gone to so much trouble to hide experimental findings that weren’t ultimately all that revealing? Agency officials claimed the program had been a colossal failure, leading to mocking headlines like the “The Gang That Couldn’t Spray Straight.” Perhaps the agency wanted the world to assume that MKUltra was a bust, and to forget the whole thing.

The CIA seems to have pared MKUltra back in the mid-’60s, according to congressional testimony and surviving financial records, but Jolly West’s government-funded research continued apace. Late in the fall of 1966, West arrived in San Francisco to study hippies and LSD. Tall, broad, and crew cut, with an all-American look in keeping with his military past, he cobbled together a new wardrobe and started skipping haircuts. He secured a government grant and took a yearlong sabbatical from the University of Oklahoma, nominally to pursue a fellowship at Stanford, although that school had no record of his participation in a program there.

When he arrived in Haight-Ashbury, West was the only scientist in the world who’d predicted the emergence of potentially violent “LSD cults” such as Charles Manson’s Family. In a 1967 psychiatry textbook, West had contributed a chapter called “Hallucinogens,” warning students of a “remarkable substance” percolating through college campuses and into cities. LSD was known to leave users “unusually susceptible and emotionally labile.” It appealed to alienated kids who would crave “shared forbidden activity in a group setting to provide a sense of belonging.”

Acid, he wrote, made people more difficult to hypnotize; it was better to pair hypnosis with long bouts of isolation and sleep deprivation.

Another of his papers, 1965’s “Dangers of Hypnosis,” foresaw the rise of dangerous groups led by “crackpots” who hypnotized their followers into violent criminality. He cited two cases: a double murder in Copenhagen committed by a hypno-programmed man, and a “military offense” induced experimentally at an undisclosed U.S. Army base. (It’s not at all clear that the latter referred to Shaver’s killing of Chere Jo Horton.)

He’d also supervised a study in Oklahoma City, in which he’d hired informants to infiltrate teenage gangs and engender “a fundamental change” in “basic moral, religious or political matters.” The title of the project was “Mass Conversion,” and it had been funded by Gottlieb.

In the Haight, West arranged for the use of a crumbling Victorian house on Frederick Street, where he set up what he described as a “laboratory disguised as a hippie crash pad.” The “pad” opened in June 1967, at the dawn of the summer of love. He installed six graduate students in the “pad,” telling them to “dress like hippies” and “lure” itinerant kids into the apartment. Passersby were welcome to do as they pleased and stay as long as they liked, as long as they didn’t mind grad students taking notes on their behavior.

According to records in West’s files, his “crash pad” was funded by the Foundations Fund for Research in Psychiatry, Inc., which had bankrolled a number of his other projects, too, across decades and institutions. Dr. Gordon Deckert, West’s successor as chair at the University of Oklahoma, told me that he found papers in West’s desk that revealed that the Foundations Fund was a front for the CIA.

This wouldn’t have been the agency’s first “disguised laboratory” in San Francisco. A few years earlier, the evocatively titled Operation Midnight Climax had seen CIA operatives open at least three Bay Area safe houses disguised as upscale bordellos, kitted out with one-way mirrors and kinky photographs. A spy named George Hunter White and his colleagues hired prostitutes to entice prospective johns to the homes, where the men were served cocktails laced with acid. The goal was to see if LSD, paired with sex, could be used to coax sensitive information from the men. White later wrote to his CIA handler, “I was a very minor missionary, actually a heretic, but I toiled wholeheartedly in the vineyards because it was fun, fun, fun.”

At the Haight-Ashbury pad, though, West’s motives were vague. No one seemed to have a firm grasp of the project’s purpose — not even those involved in it. The grad students hired to staff West’s “crash pad” lab were assigned to keep diaries of their work. In unguarded moments, nearly all of these students admitted that something didn’t add up. They weren’t sure what they were supposed to be doing, or why West was there. And often he wasn’t there.

One of the diaries in West’s files belonged to a Stanford psychology grad student who lived at the pad that summer. The experience was aimless to the point of worthlessness, she wrote. When “crashers” showed up, “no one made much of a point of finding out about [them].” More often, hippies failed to show up at all, since many of them apparently looked on the pad with suspicion. “What the hell is Jolly doing, it is like a zoo,” the student fumed. “Is he studying us or them?”

When West made one of his rare appearances, he was dressed like a “silly hippie”; sometimes he brought friends to the house. Their general attitude, she wrote, “was that this was a good opportunity to have fun. … They spent a good deal of the time stoned.” She added, “I feel like no one is being honest and straight and the whole thing is a gigantic put on. … What is he trying to prove? He is interested in drugs, that is clear. What else?”

In December 1974, MKUltra finally came to light in a terrific flash of headlines and intrigue. Seymour Hersh reported it on the front page of the Times: “Huge C.I.A. Operation Reported in U.S. Against Antiwar Forces.” The three government investigations that followed — the Rockefeller Commission, Church Committee, and the Kennedy-Inouye Select Committee hearings — looked into illegal domestic activities of various federal intelligence agencies, including wiretapping, mail opening, and unwitting drug testing of U.S. citizens.

The Church Committee’s final report unveiled a 1957 internal evaluation of MKUltra by the CIA’s inspector general. “Precautions must be taken,” the document warned, “to conceal these activities from the American public in general. The knowledge that the agency is engaging in unethical and illicit activities would have serious repercussions.” A 1963 review from the inspector general put it even more gravely: “A final phase of the testing of MKUltra products places the rights and interests of U.S. citizens in jeopardy.”

The Church Committee found that MKUltra had caused the deaths of at least two American citizens. One was a psychiatric patient who’d been injected with a synthetic mescaline derivative. The other was Frank Olson, a military-contracted scientist who’d been unwittingly dosed with LSD at a small agency gathering in the backwoods of Maryland presided over by Gottlieb himself. Olson fell into an irreparable depression afterward, which led him to hurl himself out the window of a New York City hotel where agents had brought him for “treatment.” (Continued investigation by Olson’s son, Eric — dramatized by Errol Morris in the series “Wormwood” — strongly suggests that the CIA arranged for the agents to fake his suicide, throwing him out of the window because they feared he would blow the whistle on MKUltra and the military’s use of biological weapons in the Korean War.)

The Statler Hotel in New York, N.Y. where Frank Olson fell to his death.

Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The news of Olson’s death shocked a nation already reeling from Watergate, and now less inclined than ever to trust its institutions. The government tried to quell the controversy by passing new regulations on human experimentation. Gottlieb’s destruction of the MKUltra files was investigated by the Justice Department in 1976, but, according to the Times, “quietly dropped.” Gottlieb had testified before the Senate in 1977 only under the condition that he received criminal immunity.

The Senate demanded the formation of a federal program to locate the victims of MKUltra experiments, and to pursue criminal charges against the perpetrators. That program never coalesced. Surviving records named 80 institutions, including 44 universities and colleges, and 185 researchers, among them Louis Jolyon West. The Times identified West as one of less than a dozen suspected scientists who’d secretly participated in MKUltra under academic cover.

Yet not one researcher was ever federally investigated, nor were any victims ever notified. Despite the outrage of congressional leaders and more than three years of headlines about the brutalities of the program, no one — not the “Black Sorcerer” Sidney Gottlieb, nor senior CIA official Richard Helms, nor Jolly West — suffered any legal consequences.

______________________________________________–

This article is an adapted excerpt from “Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties.”

Go to Original – theintercept.com

Tags: CIA, Drugs, Human Experiment, Human Rights, LSD Research, MKUltra Mind Control CIA, Politics, Power, Science and Medicine, US Military, USA, Violence

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.