Drug Taxis and Impotent Police: The Avalanche of Cocaine Hitting Europe

EUROPE, 2 Dec 2019

Der SPIEGEL Staff *– TRANSCEND Media Service

28 Nov 2019 – Drug syndicates are flooding Europe with very pure cocaine. Consumers need only send an encrypted text and a dealer will show up at their doorstep. And the authorities are all but powerless to stop them.

March 4 is shaping up to be another gray and dreary winter day in Herzfelde, Germany. All is silent and still. The temperature is close to freezing and the town has just received a dusting of fresh snow.

A sound in the distance grows louder and materializes into a line of vehicles speeding down Rüdersdorfer Street. Police officers spill out. They bust down doors, canvas the area with sniffer dogs and begin tearing apart a VW bus and a Chevy Camaro.

It was the snow that drew them — not the stuff of snowball fights and slippery walkways, but a pure, white powder that goes for 70,000 euros ($77,149) a kilo in Europe.

The authorities find 12.8 grams of cocaine stashed over a third-floor stairwell and another 214.3 grams in a garage. There are also micro scales, plastic vials and a shoebox full of cash. All an hour’s drive east of Berlin.

At a gas station near the edge of town, they apprehend the man behind the illicit operation. He is identified as René F., 42, a car salesman-turned-drug-dealer.

F. didn’t work alone. He employed his son Mike, his ex-wife Natalia and his new girlfriend’s son, Otto. It was a flourishing family business that offered same-day delivery. One phone call was all it took for customers to place an order. In the Berlin nightlife scene, it’s known as the “cocaine taxi.”

Everything was going smoothly until March 4.

More Cocaine than Ever Before

Cocaine. Coke. Charlie. An intoxicant for those with disposable income. A party drug. Not exactly the first thing that comes to mind when one thinks of Herzfelde, an otherwise sleepy town, population 1,750, in eastern Germany. The closest thing to nightlife here is a condom dispenser on Main Street.

If the raid earlier this year showed anything, it was how far-reaching cocaine’s global supply chain has grown — and how insatiable demand for the drug has become.

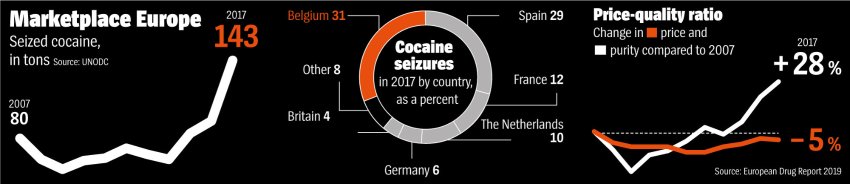

Never before has there been so much cocaine on the market in Germany, in Europe or around the world, investigators say. And the stuff that is available has never been purer. Some estimates put the average level of purity at 70 percent or higher.

It’s never been easier to procure the drug, either. Consequently, more people are sniffing it. The question of what cocaine can do to a society already afflicted by a compulsive urge for self-improvement has never been more pressing.

In Lisbon, where the headquarters of the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction is located, there is talk of a “big boom.” Germany’s Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) has also recorded a “dramatic increase” since 2016. One Interpol investigator says in his 14 years on the job, he’s never experienced anything like this.

Things aren’t likely to slow down anytime soon. “The global cocaine glut has yet to reach its peak,” warns Kevin Scully, the chief drug hunter at the European headquarters of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Quantities will “go up again compared to 2018,” he says. That goes for Germany as well.

That kind of forecast doesn’t require complicated math, just simple logic. In Colombia, the world’s No. 1 producer of cocaine, the amount of land used for cultivating coca has skyrocketed, according to the United Nations. The same is true for Peru, No. 2, and Bolivia, No. 3.

And all that cocaine has to go somewhere. In Germany, demand for cocaine has “risen sharply,” as Niema Movassat, the Left Party’s drug policy spokesman in parliament, points out. What’s more: There is hardly a business more worthwhile for criminals. In South America, a kilo of coke goes for $1,000 (906.50 euros). By the time it gets to dealers in Europe, they’re paying $25,000 to get it across the Atlantic. On the street here, that same kilo can fetch as much as $70,000. There are few other areas of business that are more lucrative for criminals.

A Well-Oiled Machine

The cocaine trade has become a well-oiled machine. It’s almost as if the drug dealers had brought in professional business consultants to analyze their operations. Sure, there’s still the usual violence, such as the recent murder of a lawyer in Amsterdam. But the industry has also grown more efficient. It relies on economies of scale and bulk purchases, precise divisions of labor and just-in-time supply chains. And, of course, it’s constantly innovating — on the lookout for the next, even more sophisticated smuggling method. In the end, the cartels can sit back and rely on the sheer power of the masses. The bigger the avalanche, the less important the things are that get in the way.

News reports of customs agents seizing multiple tons of cocaine in a single bust — 4.5 tons in July in Hamburg, 1.5 tons a few days later — are merely symbolic victories. In truth, investigators know little about the perpetrators or their operations.

What they do know is that the record amount of cocaine they found in 2018 was a reliable indication of the record amount of the drug they did not find. Interpol estimates that for all its efforts, 95 percent of shipments slip through undetected.

As the volume of cocaine flowing into Europe grows, so do the concerns of politicians, who have long lost sight of the drug problem, of investigators, who openly admit they are powerless, and of doctors, who know just how dangerous cocaine can be.

For this report, DER SPIEGEL and its partners at the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network spoke to coca farmers in Colombia and consumers in Germany about the reasons behind and consequences of the boom. Documents provided insights into how large-scale drug dealers set up their billion-dollar, B2B-like businesses — and how small-scale dealers organize their local, B2C operations, distributing product in baggies and tiny vials.

Joao Matias, an analyst with the EU’s anti-drug agency, estimates that snorting cocaine will increasingly seem normal. People’s inhibition thresholds will become lower and consumption will increase. The effect this will have on Germany cannot be known for another few years. “The effects of the cocaine glut are on the way,” warns Karl Lauterbach, a health expert with Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD). But he can say this much: “Cocaine is cheaper, better and therefore much more dangerous than before. In the future, we can expect more deaths.”

The Consumers

Lisbon is a perfect microcosm of the cocaine trade. During the day, down near the Tagus River, the EU’s drug officials pore over the numbers. Come closing time, cocaine can be purchased with ease higher up in the city, in the Bairro Alto bar district — however much you want, wherever you want.

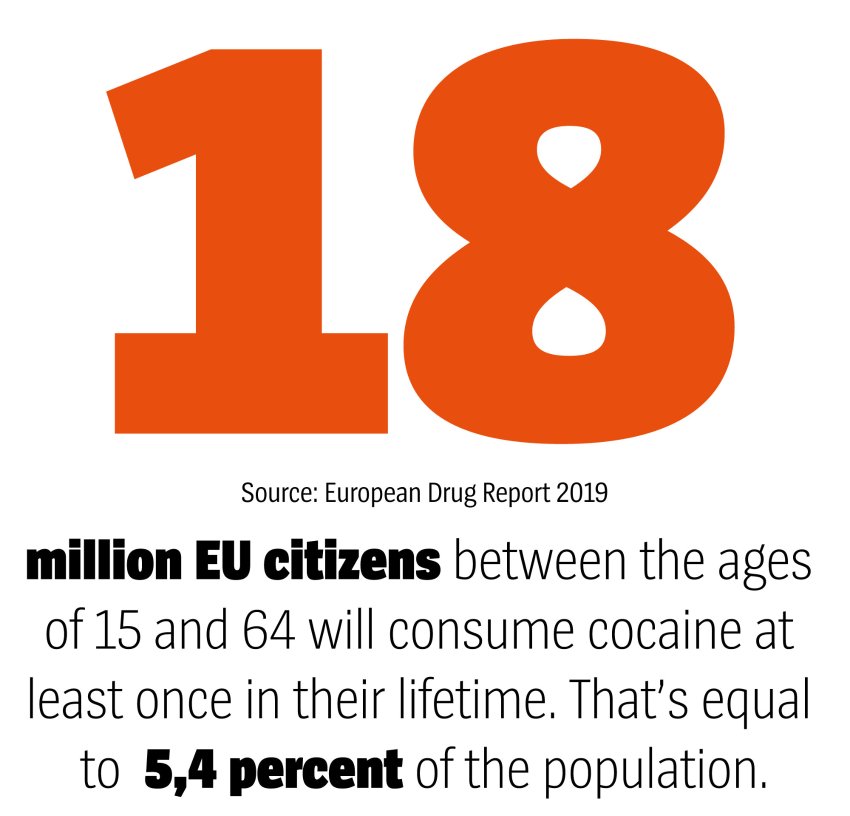

Europe’s anti-drug officials work downtown in a modern office building made of glass and white stone. There, they attempt to understand and explain the cocaine wave. According to the statistics, some 3.9 million Europeans took cocaine in 2017. By last year, that number had jumped to 4 million. That’s not a dramatic increase, but the trend is clear.

Just over 2 percent of young people between the ages of 15 and 34 — the most susceptible age group when it comes to taking drugs — snorted cocaine in 2017. On a country level, the figures varied slightly. Only 1.2 percent of German youths do coke, for instance. That’s considerably less than in Holland (4.5 percent), Denmark (3.9 percent) or France (3.2 percent). At first glance, these figures seem to suggest cocaine is a major problem in other countries but not in Germany. But the German figure is from 2015, before consumption really took off.

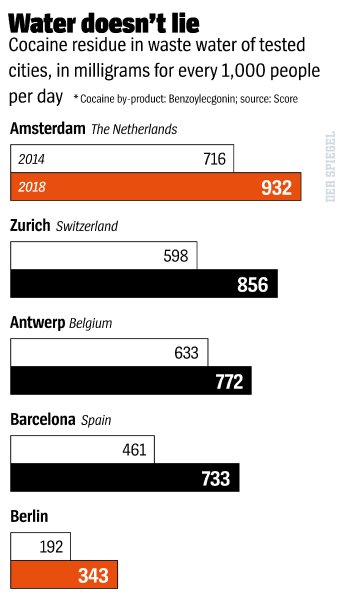

One thing alarming EU officials across Europe are waste water samples. “Water doesn’t lie,” says Laurent Laniel, the anti-drug authority’s chief analyst. Of the 38 countries that had their waste water tested in 2017 and 2018, 22 reported increases in traceable levels of cocaine, which enters the water through people’s urine. In Berlin, those levels were almost twice as high in 2018 as they were in 2014. In Dortmund too. Spikes were recorded on weekends in particular.

The Berlin police say this is because more people are taking cocaine, but European drug officials aren’t so sure. It could also be attributable to the same repeat offenders simply doing more drugs or the fact that the cocaine on the street today is more pure. But one thing is certain: No other drug puts more people in the hospital in Europe. In Berlin, cocaine has overtaken heroin as the drug with the highest death rate. In all of 2018, 35 people died from using cocaine. By the end of July 2019, that number had already hit 25.

In party cities like Berlin, less than a gram of cocaine goes for 50 euros.

Fotos: Dedmityay/ Getty Images / iStockphoto; Ziviani/ Getty Images/ iStockphoto

Everything under Control

Back in Bairro Alto, street dealers stand amid throngs of party tourists, tapping their noses and asking unabashedly, “Cocaine, cocaine?” One puts his arm around passers-by, introduces himself as “Pablo Escobar,” and boasts about having “the best stuff in town.” It’s all very casual. A gram costs 50 to 60 euros and you can even test it because, as “Escobar” and the others promise, it’s “no shit” that they’re selling here.

Bairro Alto was where DER SPEIGEL ran into Lukas, a 27-year-old PhD student who uses an alias to cover up the fact that he does drugs.

He first took cocaine two years ago with some friends from college. Ever since, he has done it around 10 to 15 times a year, and only when there’s something to celebrate: a birthday, their friendship — sometimes just life in general. They do it when they want to feel prosperous and decadent. They only do 0.2 or 0.3 grams each, never more. Lukas describes his high: “You feel clear-headed. You know exactly what you need to say or do. You let it all out. You feel like you have everything under control.”

Lukas says he has no trouble keeping his cocaine consumption under control. He doesn’t think he could ever become addicted. He’s also aware that the drug doesn’t actually make him smarter, that it only feels that way. He has everything under control, so he doesn’t understand why cocaine is so much more stigmatized than alcohol or nicotine. People get downright “hysterical,” when they talk about cocaine, he says.

Lukas could be the kind of person who can use cocaine recreationally his entire life without becoming addicted. Or maybe not. A lot of a person’s susceptibility to addiction has to do with their psyche. The phrase doctors use is “addictive personality.”

Lukas might one day be 50-years-old and just fine. Or he might keel over and die. Heart attacks are one of the potential long-term effects of cocaine use. Unlike marijuana or hash, cocaine doesn’t calm a person down. It pumps them up. It gets a person’s heart racing and it attacks the heart and brain vessels.

Officially, only 93 people died in 2018 in Germany from cocaine use. Their deaths were seldom caused by an overdose but by a collapse of their cardiovascular system. In many cases, no one suspected it was cocaine use that had come back to haunt its victims so many years later.

Everybody Does It

For experts like the drug critic Rainer Thomasius from the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, this is what makes cocaine such a mixed bag: everyone can react to it differently. Thomasius says the drug has a “high potential for psychological dependence.” For anyone who wants to escape their dreary everyday life and live in a world in which everything seems to be working for them, cocaine can be a seductive respite. It offers a soothing, get-me-out-of-here experience that a person could crave again, again and again.

Nevertheless, no more than 10 percent of people who do cocaine are considered hardcore users — the ones who snort the drug more than 50 times a year. Most are recreational users, people who have lives, jobs or families. They are managers, politicians, professors, creatives. You wouldn’t notice at first glance that they use cocaine. In fact, you wouldn’t even notice at second glance. To be sure, you’d have to examine their nasal septum for holes.

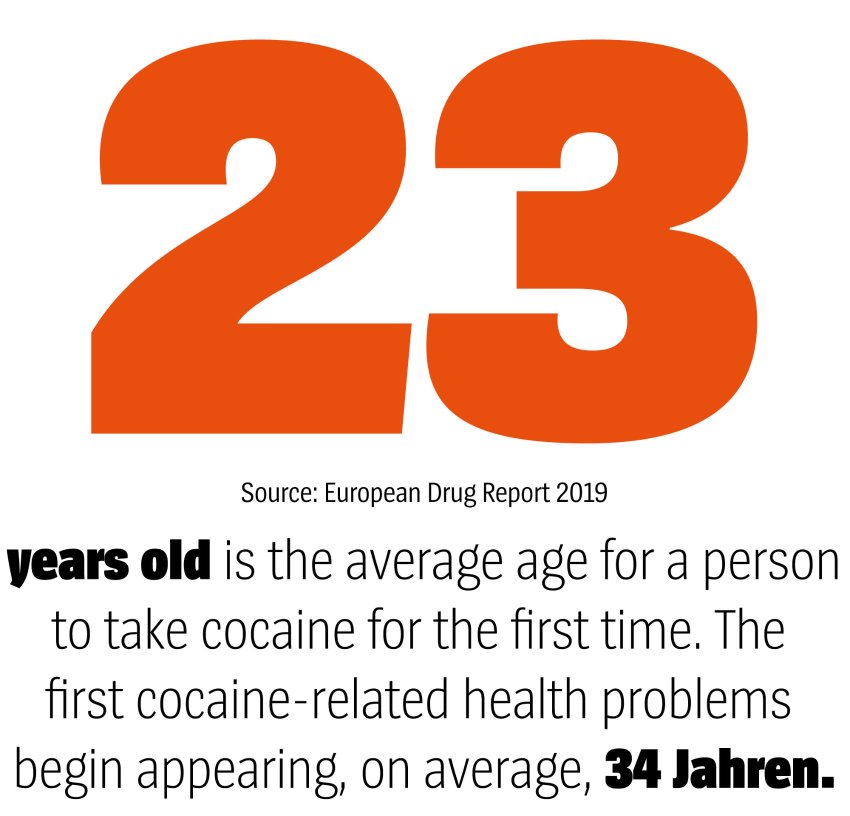

That these people appear to have their cocaine use under control, and not vice versa, may also be due to the fact that cocaine is expensive. Many people can’t afford it until they start making money. For some, this isn’t until they’re 20, maybe as late as 25. By that point, according to Thomasius, a person’s personality is more fully developed and their risk of addiction is lower. And yet, time and again, there are new users who become delusional after doing coke for only a short amount of time. People who, after a few years, can’t concentrate on anything except the next line of blow.

A Life under the Influence

It wouldn’t take much for Florian, a student from Berlin, to become one of these lost souls. Florian isn’t his real name, but he did begin taking drugs when he was 20 and got sucked in by the club scene in Berlin, where dealers often stand in front of the bathroom stalls. For three years, Florian was an intense coke user. Today, he realizes his habit isn’t sustainable. Not unless he wants to become a junkie.

“This stuff makes me more self-confident the more I take. I can make me start acting pretty smug,” he says. Once he was sitting with friends at a bar in Hamburg. The next table over was occupied by several Englishmen who wanted to talk. Florian kept giving them the runaround and felt better about himself with every rude remark.

“I enjoyed making a show of my arrogance. I was this cool guy who did the cool drug. And I increasingly acted this way even when I wasn’t high,” Florian says. He was impatient, aloof, contemptuous. “I could hardly stand my own friends sometimes. And strangers? Forget it.”

Similar to Lukas, Florian considered himself to be a “fairly circumspect consumer” too at first. Then he noticed how his life gradually began to revolve more and more around cocaine. He remembers the time he was at a family get-together, sitting at a table outside with good food, drinks, good company, a nice atmosphere, “and then I caught myself thinking how nice a line of coke would be right now.”

Florian hates the moments in which cocaine takes control of his thoughts and won’t let go. He wants to take back control. He’s only done coke once since January, he says. But quitting altogether? Why should he? Half the people in his philosophy department do cocaine, he says. Then there’s his friend who works in a cafe and says he wouldn’t be able to stand in the kitchen so long without a line every now and then. And the mother of one of his friends, who works at a casting agency. And an acquaintance of his father’s, a businessman. There’s even the young woman who he recently met while playing ping-pong and who seemed so inconspicuous — even she does coke. Everyone does it, Florian says, and the quality is good. Plus, it’s easy to get.

The Producers, the Big Dealers, the Small Dealers and the Investigators

The Producers

Colombia is the country where cocaine’s global journey begins. From the fields of the province Putumayo, to the clubs of New York, Moscow and Berlin. Overlooking a coca plantation, on a wide porch he built just a few months ago, sits a man with a goatee and a brimmed cap. His name is Sneider, at least that’s what everybody calls him. He gazes onto five hectares of green, chest-high coca shrubs. They are his pride and joy, his source of income, his life.

Sneider cleared the area himself. It was hard work not made any easier by the heat and humidity of the jungle. That’s why he can hardly believe someone would ask him in all seriousness: Why don’t you grow potatoes? Or coffee? Corn? Rice? Anything but coca. You might as well ask Sneider if he wants to hold his breath for 15 minutes to save the world’s climate.

“Of course, I have to grow coca here,” he says. “It’s the only thing that fetches enough money.” It takes him between six and seven hours by boat to bring his harvest to the next large town. With potatoes or corn, he would barely make back the money he spends on fuel. And if he makes coca paste, he doesn’t even have to leave home. The buyers come to him.

Sneider looks down a small embankment leading to the river, his only connection to the outside world. Way out here there is no electricity, no phones, no sewage system, no doctor. But also no police, no judges — strictly speaking, no law. It’s Colombia’s age-old problem. There’s simply too much land for too little government. For Sneider, the coke farmer, this is less of a problem than a solution.

Left-wing FARC guerillas have taken over control of the area again. Whether it’s the FARC or the mafia, they all live from cocaine, more or less. For a while, it was less. The government was at war with FARC and since the mid-90s, it sent not only soldiers but also airplanes armed with the plant-killer glyphosate. They figured no coca meant no money. And if there was no money, there could be no guns. Of the 163,000 hectares of coca fields in 2000, only 48,000 were left by 2013.

More Land Than the Government Can Handle

Then came the peace negotiations, and peace was good for men like Sneider. For one, it no longer rained glyphosat. And after the FARC rebels came the drug gangs, financed by the cartels in Mexico with their ravenous hunger for expansion. A Western intelligence service estimates there are 209,000 hectares of coca fields in Colombia today. “The total area under cultivation has exploded,” it says.

Almost 70 percent of the world’s cocaine stems from the fields of Colombia. The rest comes from Bolivia and Peru — two more countries with more land than their governments can handle. A German investigator with the BKA had this to say about Bolivia in an April report that was supposed to remain confidential: “Cocaine combatance is no longer taking place on a notable scale. There is hardly a shred of political will.” The rest was bitingly sarcastic: “The statistics with which Bolivia counters any criticism from abroad are not worth the exceedingly patient paper they are printed on.”

From the jungles of the major cocaine producers, the drug is transported to the coasts of South America, mostly to the container ports in the east. “Brazil is pushing forward to dizzying heights,” the BKA report states, going on to claim that Brazil has been the main hub for shipping cocaine to Europe since 2013. Along the supply route lies a country that doesn’t even bother to feign a hypocritical political will in the fight against drugs: Venezuela. Since the U.S. oil embargo was imposed, which removed the main lubricant for the country’s economy — and the corrupt government of the populist Nicolas Maduro — cocaine has become increasingly important as a substitute.

“Our investigations have shown that both members of the government and high-ranking military personnel are involved in drug trafficking,” one U.S. drug hunter says of Venezuela. The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation, more commonly known as Europol, has made a similar observation: “More and more cocaine is flowing through Venezuela to Europe.” International drug gangs ensure unhindered passage across the Atlantic.

The Big Dealers

When a police SWAT team smashed in the door to a house at 4 a.m. on Dec. 5, 2018, Gioacchino R., Gino for short, didn’t seem particularly fazed. It was not his first encounter with the law. “Mr. R. seemed very calm and said he was familiar with the procedure from a former life,” the state criminal police office later noted. Gino R., a resident of the western German city of Solingen, hailed from Palermo in Sicily, Italy. He allegedly had family ties to the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta mafia and a litany of previous convictions back home for drugs, fraud and assault against motorists on the highway. He owed the most recent early morning house call by the police to his alleged role in a cocaine gang.

R.’s was not one of the street gangs slinging coke one gram at a time, but the kind of major dealer that rarely gets ensnared in investigators’ nets. The kind that has its own people in South America and its own container transports to Europe. There were 84 arrests on that December day in 2018; 47 of the accused were in Germany alone. The sting, “Operation Pollino,” was named after a mountain in Calabria. It offered rare insights into this otherwise opaque, large-scale business.

The public prosecutor’s files reveal that for years, Gino R. had adopted the camouflage of a nobody. He came to Germany, lived with a relative in Lüdenscheid, helped out in a restaurant in Düsseldorf and earned less than 1,200 euros a month. Later, he worked on construction sites and his girlfriend had to work as a cleaner so that the two would have enough money to last them until the end of the month. It was a life lived on the edge, like so many others.

But one thing did stand out to investigators. They wondered why a man devoid of any other notable qualities would act so “extremely conspiratorially.” And another thing didn’t seem to fit the bill: Gino R. had co-founded a company in January 2015 that ostensibly imported charcoal from Colombia and wood from Guyana. Reddish wood of the wamara variety, hardly in demand in Western Europe and practically unsellable. Why would a man with no money, no command of German and no knowledge of specialty timber — or business in general for that matter — pack something like this into an overseas container headed to Europe?

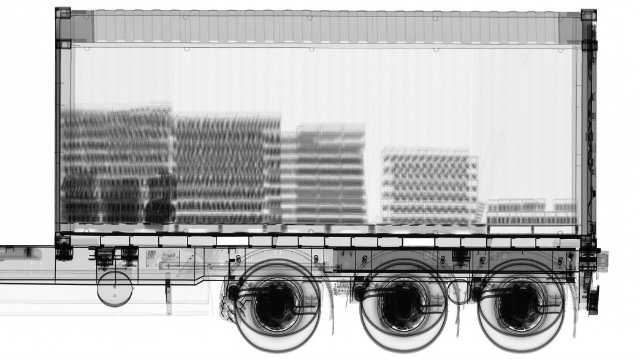

The Port of Antwerp, where an estimated 95 percent of cocaine shipments make it through. Oliver Tjaden/ Laif/DER SPIEGEL

Increasingly Brazen Smugglers

More money is made with cocaine than with any other drug — 300 billion euros worldwide, according to German intelligence officials. Europe is the second-largest market after North America. A quarter of the world’s cocaine users live in Europe, the UN estimates. And where the demand is, the supply must follow. The authorities have seized quantities of the drug on sailing yachts, speedboats and fishing boats. Recently, a private jet with 600 kilos of coke onboard flew from Uruguay to Nice, France, and on to to Basel, Switzerland. Premium shipping. On the lower end of the market, couriers hide the drug in condoms, which they swallow, and stuff it under wigs. They even conceal it in breast implants.

The preferred route to Europe, however, has long been the overseas container. One of the greatest seizures of all time — 19 tons of blow confiscated in June — was distributed between multiple containers onboard a freighter in Philadelphia. From there, the containers were supposed to head to Rotterdam. Thousands of containers like this can fit onto a single ship. Millions of them criss-cross the oceans. Each has enough room to hide a few hundred million dollars worth of cocaine, depending on how full the gangs pack the containers and how much they stretch the goods later.

Whereas drug gangs used to go to the trouble of concealing their product in things like pineapples, today they simply stow it in sports bags or boxes. In South America, they break into an already loaded container and toss in the cocaine. Accomplices in Europe will then retrieve it, usually while the container is still in the port. Investigators refer to this method as, “rip-on, rip-off.” The companies that dispatched the container generally have no knowledge of what goes on.

Of course, this did not apply to Gino R. and his company. The fact that police busted in his door at 4 a.m. had to do with Giuseppe T., a mafia boss in Italy. The man with the nickname “Principale,” or boss, was afraid of being liquidated by other mafiosi. In July 2015, he went to the police and told them everything, including about Gino’s small company in western Germany and the ‘Ndrangheta’s larger operations in Colombia.

During the last coke wave, drug barons like Pablo Escobar and the Ochoa brothers from Colombia dominated the supply chain to North America and Europe. Now the mafia and other European gangs have their own leaders in South America. According to Interpol, Albanians in particular are the new big players in the coke business.

“The groups in Europe want to get their stuff directly from the producers, so that they save on transport and get a bigger piece of the value chain,” explains Interpol investigator Andres Bastidas. Sales representatives collect the money of the mafia families or dealer rings at home, put together a shopping list and buy in bulk overseas for everyone. The goods are divvied up later in Europe. The “Principale” said he had already scraped together 2 million euros to procure cocaine, including his own money and that of other mafia figures.

Charcoal, Wood, Then Coke

The Colombians, for their part, have highly specialized gangs that handle coke cultivation, the drug laboratories and transportation to the coast. They, too, have joined forces and formed cooperatives. “This explains why cocaine is always found by the tons today,” says Interpol’s Bastidas.

The first container of Gino R.’s arrived in Hamburg in early 2015. It contained 640 bags of charcoal emblazoned with the words, “Best Quality.” Customs checked the goods and gave the green light. R., for his part, apparently didn’t care much about his imported coal. By 2017, those same bags were still lying unsold in front of a warehouse in Hürth. The next container, which arrived in Antwerp in October 2015, had wood inside. This time, the freight was abandoned in Schwalmtal.

This came as no surprise to investigators. These were trial deliveries to see whether the containers would make it through customs and to lull the authorities into a false sense of trust. New companies are regarded as suspicious. The more clean deliveries one has, the less likely future shipments will be searched.

The container with the cocaine arrived in Rotterdam on Dec. 6, 2015, and was inspected. Customs officers found five boxes, a sports bag and a Samsonite suitcase lying on a stack of boards in the back. Sniffer dogs and a forensics test confirmed: cocaine. There were 82.3 kilos with 80 percent purity. This wouldn’t pass for a large delivery nowadays, but investigators believe R. and his group intended to eventually smuggle 1.2 tons of the drug to Europe — at least according to documents in the investigation.

At first, narcotics officials in the Netherlands still assumed the company’s founder, Gino R., had nothing to do with the shipment. But by May 2017, when someone using the name, “Toto,” called R. on the phone to order 10 “bread rolls,” the police believed Gino to be part of the gang. R.’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment by DER SPIEGEL. The public prosecutor’s office intends to file charges within a few weeks.

The Small Dealers

Florian, the student from Berlin, will never cross paths with dealers in the same league as Gino or Giuseppe. His contacts are at the end of the chain, the guys on the street delivering the “bread rolls.” They often deliver via “taxi,” as the courier services are known that take orders over the phone and send a driver with the goods within a half hour. A quick drive around the block and the driver asks, “All good, man?” Florian replies, “Yeah, I’m good.” Then 50 euros changes hands, and in return Florian receives a tiny plastic vial filled with 0.7 grams of cocaine. “See you next time.”

Most of the time, Florian says, the drivers are young and, he assumes, Turkish or Arab rather than Italian. But that’s not the kind of thing you ask. “They are incredibly polite, probably because the competition is so fierce,” Florian believes. “There is an unbelievable amount of ‘taxis’ in Berlin. Some friend always has a new number you haven’t tried out yet.”

By now, the Berlin police have become aware of this fact as well. They have bundled their investigations into drug taxis in a special police department. There are 35 ongoing investigations. The Berlin police’s chief drug officer estimates that some “taxi switchboards” handle more than 100 requests a day.

Some even offer their customers discounts to gain an edge over the competition. One text message reads, “Hey, it’s me, Toni. I’ve got some great beer on offer again. Buy four, get one free.” Buy four vials of coke, get the fifth one free. And while drug deals used to take place in small, isolated circles, the EU anti-drug authority has observed a “new quality in cocaine trafficking,” because “social media is used relatively often to advertise cocaine.” On the rampant marketplaces on the darknet, customers can rate coke sellers and their product like they would on Google or eBay.

The coke taxi from Herzfelde wasn’t as well-established as its competitors, but Rene F. and his family had only just begun. They began selling in September 2018. They got their product, according to prosecutors, from a man believed to be a member of the Rammos clan, an Arab criminal syndicate in Berlin. The fact that the source of the cocaine was so well known to investigators may have explained why police placed Rene F. and his family under observation from the very beginning.

Before becoming a drug dealer, Rene F., like his wife, lived on welfare. Their son was learning to be a car salesman. According to investigators, none had any previous experience in the drug trade. The fact that such amateurs started their nascent careers with cocaine — the most expensive of all drugs — says something about the availability and the demand of the substance. In March, their brief stint as drug dealers came to a swift end. Rene was sentenced to four years and three months. The others were given probation. All pleaded guilty.

The Investigators

So was it a victory for investigators to celebrate? Not by a long mile, some say. In the port city of Antwerp, Belgium, they even have a joke for how little headway investigators are making: Did you hear? They found some bananas packed in cocaine crates at the harbor yesterday.

It’s a corny attempt at humor, but it says a lot about the situation in Antwerp. The fight against coke is lost, everyone says, whether at the EU in Lisbon or in Antwerp itself. Antwerp is lost.

Though a lot of drugs enter Europe via Africa and Spain, the Belgian port city is considered Europe’s main coke hub. It even surpasses Rotterdam and Hamburg. Of the 150 tons of cocaine confiscated in Europe in 2018, 51 were seized by investigators in Antwerp. This year, that figure had already risen to 42 tons — by the end of October. Any investigator who isn’t kidding him- or herself knows this can only mean one thing: Nowhere do the gangs try to smuggle their drugs into Europe more often, and nowhere do they succeed so easily.

The port the smugglers love so much is the largest in the world in terms of surface area. It covers 120 square kilometers and it is designed to process containers as quickly as possible. Some 7 million of them pass through Antwerp every year. Nothing is permitted to tarnish the port’s appeal to the rest of the world. Speed, investigators say, is even more important than safety. And a police task force with 40 officials can’t do much to change the situation. “Everything in the port that is good for the economy also benefits the criminal gangs,” says Manolo Tersago, the task force’s ranking officer. Asked what he would need to make a bigger difference, his answer is simple: more personnel “as quickly as possible.” He simply doesn’t have the resources to search for drugs, money or the people pulling the strings.

“For years, the port has been infiltrated by cartels from Albania and Morocco,” laments one narcotics officer. As early as 2017, a confidential report by the Antwerp police described the port as an enclave over which the state had relinquished control to the drug mafia. “They don’t shy away from anything,” not even making death threats against police officers, chief investigator Tersago says.

Bribing Port Workers

But things don’t even need to escalate that far. The gangs earn so much money “they can buy anyone they want,” Tersago says. And they do. Around 60,000 people work directly in the port. The gangs even send recruiters to cafes and gyms. They’re always on the lookout for people who can help them get the product out of the containers. Hauling a steel box to a remote location for a couple of hours costs a container stacker mere minutes, but according to Tersago’s estimates, it can earn him between 25,000 and 75,000 euros.

The jackpot for gangs is bribing a so-called selector, the customs officer who decides whether a container that has just been unloaded is searched or waved through. A man used to work in the Port of Rotterdam who earned 250,000 euros for every 100 kilos of coke he let slip through. But that was just one side of the coin. After the man was arrested in 2015, he said, “They knew everything about me, even where my children went to school.”

A bribed customs officer — what could be better for crime syndicates? In fact, business isn’t all that much worse without them. Without a tip of where to look, investigators can easily get lost in the depths of a ship’s holds. Late last September, three customs officers climbed into the belly of a 300 meter-long container ship in Hamburg. They had to use a 30-millimeter percussion drill to loosen 20 bolts to open the hatch to the ballast tank. Five minutes later, they closed it. And that was just one hatch.

The ship had hundreds of hatches like this. Thousands of hollow spaces. And that’s in addition to the 14,000 containers when the ship is fully loaded. A few hundred of these ships arrive and unload their cargo every year. The port’s annual capacity is 5.4 million containers. If one of them is up on the loading deck, in the second row from the top, boxed in by several other containers, how are customs officials supposed to get at it? “We often don’t,” a customs official admits.

They could, of course, have it unloaded. Like in all large ports, computer programs flag suspicious containers. They check whether the containers are from South America, what they allegedly contain and which company is importing them to Europe. Customs officials could have a container transported to an X-ray facility, which can process a good 100 units a day. But that takes time, and if nothing is found, as is usually the case, the question arises as to whether it was worth the trouble. The port of Hamburg, too, places a high value on speed.

“You have to be able to lose in this job,” the customs officer says. The fact that they made the biggest find of all time in Germany last summer — 4.5 tons — certainly raised morale. They used to celebrate when they seized 20 kilos of coke. But did anything happen to the market because 4.5 tons of product didn’t materialize? Have prices risen because there is less supply? Not even close.

“Despite record quantities seized, there has been no perceivable change in perpetrators’ behavior,” the BKA wrote in April. This “only leads to one conclusion, that the pain threshold has not yet been reached.” Günther Losse, the head of the Hamburg customs unit, says, “We suspect that the lion’s share gets through.” The BKA confirms: “This would mean that enormous quantities of cocaine must make it onto the European market.” Investigators unanimously agree.

No Good Solutions

Many narcotics officials have little hope of winning the fight. The head of customs in Hamburg, Rene Matschke, says, “We never stumble upon fixed structures and therefore don’t know who’s doing the importing. We rarely get close to the bosses.” Interpol’s Andres Bastidas says, “It has become much harder to catch the big fish.” Peter Keller, the chief drug investigator at the customs office in Cologne, says, “There’s too much coke on the market and we can only find the tip of the iceberg.”

Politicians are also to blame for the seemingly hopeless situation. The German Customs Investigation Bureau says they “aren’t terribly interested anymore” in drug smuggling. Europol says the same thing: Drugs have “long disappeared from the agenda.” In Antwerp, for instance, police officers were withdrawn from the port after the attacks in Brussels in order to hunt down terrorists. At customs in Hamburg, more than 10 percent of ship inspection jobs are unfilled. The search for undeclared workers seems to be a higher priority.

In its search for answers, DER SPIEGEL approached Daniela Ludwig, Germany’s federal drugs commissioner. She sees the root of the problem far away, in Colombia. She has nothing to say about Germany. Karl Lauterbach, the SPD’s health expert, is at least willing to accept the criticism: “Investigators simply lack the means. The subject of drugs has not received the attention it deserves.”

This has prompted the Green Party’s domestic policy spokeswoman, Irene Mihalic, to call for more money to be allocated not only to police, but also to education and therapy. Movassat, the Left Party’s drug policy spokesman, proposes a much more radical solution: He’s for decriminalization and a government-controlled cocaine trade — a regulated levy. He says it’s the only way to chip away at the narcos’ global power and dry up their billion-dollar business.

That would be the most radical solution. And the most desperate. The fight against cocaine seems long lost, whether in the fields of Colombia, the ports of Europe or the streets of Berlin. The avalanche is here. What can possibly stop it now?

_______________________________________________

*Jürgen Dahlkamp, Jörg Diehl, Gunther Latsch, Claas Meyer-Heuer, Juan Moreno, Jörg Schmitt, Katja Thimm, Andreas Ulrich

Tags: Cocaine, Colombia, Drug Dealers, Drugs, Economics, Europe, FARC, Latin America Caribbean

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.