Myanmar’s For-Profit Genocide

ASIA-UPDATES ON MYANMAR ROHINGYA GENOCIDE, 13 Jan 2020

Wendy Bone | The Investigative Journal – TRANSCEND Media Service

Brutal operations against the Rohingya minority and stealing their land in Rakhine are crimes under international law — violations supported by Myanmar’s military business ties, foreign companies and arms deals.

10 Jan 2020 – Arif Ismael ran an after-school tutoring program at his home before the mobs arrived to burn it down.

Arif lived with his family in Sittwe, the capital of Myanmar’s Rakhine State, where he taught English, the Myanmar language, and economics. His program for junior high school students had been running well for the past year, despite government limitations imposed on him as a Rohingya Muslim, Rakhine’s largest ethnic minority. For the past 40 years, Rakhine’s more than one million Rohingya had been denied higher education, proper medical care, and citizenship in the country they had lived in for generations. Since graduating from Sittwe University in 2008 with a degree in geography, Arif had wanted to earn a Master’s, but his ambitions were out of the question since Rohingya were not permitted to obtain any degree higher than a Bachelor’s. Job prospects were also severely limited. Arif was barred from teaching at a government school, so he started teaching from home with some Rohingya colleagues.

Then the first wave of violence erupted against the Rohingya that would presage the brutal ethnic cleansing to come. It started on May 28, 2012, when a 26-year-old Rakhine seamstress, Ma Thida Htwe, was murdered on her way home from work in Kyaungnimaw township, 161 kilometres to the south1. Authorities said she had been gang raped, and arrested three men labelled as “Bengali Muslim,” a derogatory term for Rohingya, in connection with the crime. The men were sentenced and imprisoned, but the incident was the spark that ignited already simmering resentments in a country just transitioning to democracy after 50 years of military dictatorship. Soon after Ma Thida Htwe was murdered, Rakhine Buddhists retaliated, killing 10 Muslim missionaries returning from Yangon2.

On hearing about the violence in the townships outside Sittwe, an ominous pall fell over Arif and his colleagues. Throughout Rakhine there is widespread public perception, propagated by the government, that the Rohingya are not “indigenous” to the state but Bengali “invaders” who want to take over the land. In 2011, the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party (now the Arakan National Party) had ramped up tensions by holding seminars on the so-called invasion of illegal “Bengalis,” and a popular magazine depicted the Rohingya as “terrorists” and a “black tsunami” in reference to their dark skin3.

Until then, Arif had lived peacefully with his Buddhist friends, classmates, and neighbours. During the decades-long dictatorship of General Ne Win, Myanmar’s numerous ethnic groups collectively viewed his oppressive regime as the enemy. Now that the country was struggling towards democracy under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy, society was fracturing, and communities were becoming divided along ethnic and religious lines.

Sittwe became eerily quiet. The teashops, usually hubs of conversation, had emptied, shops were closed, and pedicabs ceased carrying housewives home from the market with their shopping4. On June 8, 2012 mobs of armed men arrived, reportedly bussed in from outlying townships—town leaders who had attempted to prevent the violence did not recognize them. The police blocked the roads where the Rohingya lived, trapping them inside their neighbourhoods and assisting the mobs in setting fire to Rohingya homes and businesses. Fears intensified at the sight of smoke billowing into the sky from other neighbourhoods. Arif and his neighbours could only wait for their homes to be next.

That time came four days later, on June 12. Arif remembers it was 12:45 pm when Rakhine Buddhist mobs appeared on the Kon Dan quarter off Main Road where he lived. Brandishing torches and machetes, they began setting fire to the houses. “We tried to defend them to protect ourselves. But we couldn’t as police were shooting at us,” Arif said. “We all decided that it was last day of our lives and we would die soon.” He saw his neighbour Mujeeb, who had been trying to extinguish a fire set in the Islamic university, attempt to run when a mob attacked him. The police shot Mujeeb in the leg and hacked his body into pieces where he fell.

The violence left 192 people dead, 265 injured, and 8,614 houses destroyed5. As the late afternoon sun settled over the Bay of Bengal, soaking the land in a deep red glow, the military began rounding up the Rohingya and sending them to 14 IDP (internally displaced persons) camps on the coast northwest of Sittwe.

An Open Prison

Seven years later, Arif continues to live among an estimated 128,000 Rohingya in the IDP camps6. In Google Maps the region appears to be mostly unnamed empty space, as if the thousands of Rohingya living there don’t exist.

Yet the Rohingya camps are in plain view to any passenger arriving or departing the Sittwe airport. As I arrived in Sittwe to learn what had become of the Rohingya and their homes, I could see the bamboo huts of the IDP camps huddled along the coast, parallel to the flight path of my incoming plane. The camps are spread out over a flat, open plain, vulnerable to monsoons and cyclones that blow in from the Bay of Bengal.

Rohingya in IDP camp near Sittwe.

Source: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operation (licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Arif, now 28, lives with his parents, wife and two children in one of those one-room huts of bamboo and plastic tarp. Regardless of their size, each family gets only one hut. Little work or medical care is available beyond what international non-governmental organizations provide, and the Rohingya subsist on a diet of beans, rice, and oil provided by the World Food Program.

“Life is like living in an open prison,” Arif told me through WhatsApp. I wasn’t able to meet him in person because the camps are off-limits to journalists, so a fellow journalist specializing in Myanmar had introduced us through social media. “It seems the government will never do anything for our resettlement and violated rights,” he said. “There’s no future for us. The world has been blinded and humans are hunting humans. Humans are thirsty for human blood.”

Pike Thae, a Rohingya fishing village on the Sittwe waterfront, has been destroyed and scraped of evidence.

In August 2017, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), formed by young Rohingya men in response to the 2012 violence7, killed 12 officers with homemade weapons in coordinated attacks on security posts, saying it did so because the Myanmar military (the Tatmadaw) was raping and murdering Rohingya civilians8. The Tatmadaw retaliated with a fresh wave of violence, burning entire Rohingya villages to the ground and forcing an estimated 750,000 Rohingya to flee across the border into refugee camps in neighbouring Bangladesh. During the violence, at least 24,800 Rohingya were killed, 42,000 received gunshot wounds, and 18,500 Rohingya women and adolescents were raped9.

Rakhine’s remaining 600,000 Rohingya—an estimated 470,000, mostly in the northern townships, in addition to the 128,000 in the camps—continue their stateless existence in ghettoized conditions, denied freedom of movement and defenceless against further human rights abuses and genocide. One official I interviewed from the International Organization for Migration in Sittwe said he holds out little hope for the future of the Rohingya in the IDP camps, 53 per cent of whom are children10. “It’s going to be permanent apartheid basically,” he said.

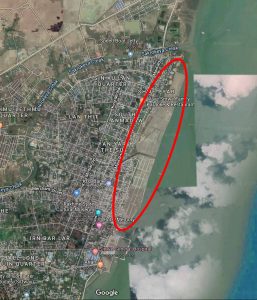

I asked Arif what happened to his home, and he sent me the GPS coordinates of its location and several photos. As with other Rohingya houses, his had been so thoroughly destroyed that almost all evidence of its existence had been erased—just a patch of grass, a fence, and a few rocks remained. A satellite image of the Pike Thae quarter on the waterfront, near where Arif lived, shows the location of the former Rohingya fishing village before the 2012 violence, now a jetty scraped clean of evidence with outlines of the roads between the houses remaining.

The village was burned down and bulldozed by authorities, their occupants forced into the IDP camps, Arif said. “Previously the Rohingya in the area were fishermen. It seems that the land on the coast is wanted for other developments, so they take it by force.”

Exploiting Ethnic Divides for Profit

Bound by the Arakan mountains to the east and the Bay of Bengal to the west, Rakhine has historically been an independent kingdom, isolated from the rest of Myanmar but with strong ethnic and economic ties to India, while Chin State to the north has links with China11. Once considered an isolated backwater, Rakhine, with its strategic location, long coastline, and largely untapped natural resources, is now highly sought after by its powerful neighbors, international corporations, and the Myanmar government.

The government’s Rakhine State Investment Opportunity Survey says that Rakhine plays a vital role in Myanmar’s economy because the state holds enormous economic potential, with “richness in natural endowments such as oil reserves, natural gas fields, and maritime resources, recreational hotspots, beaches, and historical sites” that could create employment opportunities with responsible investment12.

But the ongoing genocide of the Rohingya, a case that Gambia has recently taken to the International Court of Justice and is still trying at the time of writing, calls into question any potentially responsible investment in Rakhine. Amnesty International reports that since the wave of violence in the 2017 “scorched earth” campaign, security infrastructure has dramatically increased in the state, with military bases, helipads and roads built directly over the sites of burned Rohingya villages13.

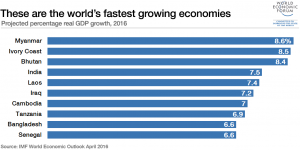

By 2017, when the Rohingya were fleeing for their lives and being forced into the IDP camps, Myanmar had become the world’s fastest growing economy, financed by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and international foreign investors14. A year later, the Myanmar Times reported that more than 60,000 foreign tourists had visited Rakhine in 2018, and that so far foreign companies had invested US$9 billion in hotels and tourism, livestock, fisheries, and oil and gas15.

Two of the state’s largest infrastructure projects include China’s KyaukPhyu Special Economic Zone, a US$7.3 billion deep-water port south of Sittwe that could displace approximately 20,000 people and damage local ecosystems, and the US$2.45 billion Thelong-Myanmar-China oil and gas pipeline, running 771 kilometres from the coast to Yunnan province.

Despite the race to industrial development and its status as Southeast Asia’s largest country by landmass, Myanmar remains the poorest country in Southeast Asia. Rakhine, with a populace largely dependent on agriculture and fishing, is one of its poorest states, with 43.5 per cent living below the poverty line compared to the national average of 25.6 per cent16.

The state’s high level of poverty partly explains the groundswell of popular support among the ethnic Rakhine majority for the Arakan Army. Rakhine’s largest and most well-organized insurgent group, the AA aims to reclaim what it says is ancestral Arakan land (as Rakhine was formerly known) by the end of 2020 under the rallying cry “Arakan Dream 2020”17.

When I was there in October 2019, fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw was centred around Mrauk U, 60 kilometres northeast of Sittwe. With its ancient pagodas and rich history, Mrauk U is the cultural heart of Rakhine and the site of the Tatmadaw’s plans to expand tourism and build a new airport. Since December 2018, however, fighting for control of the region has intensified, killing and displacing Rakhine villagers caught in the crossfire.

Kyaw San Aye, a Rakhine Buddhist who works in Sittwe’s tourism sector, was recently forced to leave Mrauk U and move to Sittwe with his family. As with thousands of Rakhine, poverty had forced him to seek employment outside Myanmar. He was working in Thailand as a waiter and sending money home to his wife when she became afraid of the fighting and begged him to return.

“Rakhine is rich in natural resources, but the people are very poor,” he said. “The oil pipeline is like a straw that sucks all our oil into China. The government gets rich, but the Rakhine people get nothing. We have no money for food or medicine. That’s why the Arakan Army fights the government, and the government divides the people and makes us fight each other.”

The lack of economic opportunities in Rakhine have also made the struggling population vulnerable to the government’s divisive propaganda, a strategy that appears to have been used with foresight to destroy Rohingya homes and villages and take their land. In September 2017, Tatmadaw Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and other high-ranking officials held a fund-raising ceremony in Sittwe, where the general spoke of “deployment of troops in advance for area clearance operations” against “extremist Bengali terrorists,” as well as plans to complete the 274-kilometre border fence on the Myanmar-Bangladesh border that would prevent the return of Rohingya refugees to their land18.

“The Bengali problem was a long-standing one which has become an unfinished job despite the efforts of the previous governments to solve it,” the general told an audience that included the heads of Tatmadaw crony companies and the nationalist organization, The Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, also known as the Dhamma Parahita Foundation, or MaBaTha, which the Tatmadaw created as an alternate power base19. He also openly declared that “absolutely, our country has no Rohingya race.”

Rohingya Land for Sale

Today, on the shore of the Kaladan River where the homes of the Rohingya fishermen of Pike Thae once stood, there’s a vast expanse of black sand—the equivalent of two square kilometres—scraped completely flat. Freighters at the edge of the jetty have replaced the Rohingya’s wooden fishing boats, and mounds of sand and bulldozers have replaced their homes.

At the perimeter next to the road, groups of Rakhine men perched on plastic stools beneath the tarps of makeshift teashops, smoking and gazing morosely out at the altered landscape beyond the barbed wire. I could feel the grit hit my mouth—the sand blows inland, clogging the lungs of staff and patients at the local hospital20. Across the road, an ornate rusty gate hung off its hinges, opening onto a vacant lot of weeds and fruit trees that once made up a garden.

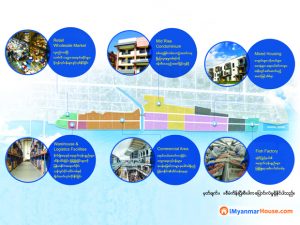

The former Rohingya Pike Thae quarter is now slated for commercial and industrial development on Sittwe’s waterfront

South Korean property developer BXT International has begun its US$10 million, 90-acre “land reclamation project”21 developing this former Rohingya village into a shopping and residential complex complete with hotels, restaurants, and shipping facilities22.

BXT International’s brochure, which I found in the lobby of a Sittwe hotel, features a topographical map of the project in the same shape and size as the land in Arif’s satellite image, and an architectural illustration of the planned shopping and housing complex that looks overly ambitious compared to the flat expanse before me. “The Waterfront Project in Sittwe uses land-based technology based on Singapore’s famous Marina Bay Sands, a 55-storey building, hotel, shopping centre, and casino,” the brochure says. “This is a project that should be invested in.”

The brochure also features a map of the proposed transport route from Sittwe across the Bay of Bengal to Kolkata, West Bengal. Next to the jetty, India’s Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project is hidden behind high metal doors. On October 22, 2018, India and Myanmar signed a memorandum of understanding for the construction of Sittwe Port, part of a planned multinational corridor for shipping and trade. “This land parcel is very close to the Indian port and will be a good location for trade and investment,” the brochure says, adding that it is “the first Smart City in Sittwe, Rakhine State.”

The map of the proposed “Smart City” project matches the satellite image of Sittwe’s former Pike Thae quarter.

A spokeswoman for BXT International in Yangon told me by phone that the project is 85 per cent sold and is expected to be complete in March 2020. When I asked if BXT was aware that the project was on the site of a destroyed Rohingya fishing village, she said that she knew nothing about it, but that the Myanmar Investment Commission had given the company approval. When I asked if BXT was aware of Gambia’s current case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice for the genocide of the Rohingya, she hung up. The company has not responded to emails or to messages through their Facebook site.

The Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC) is a government-appointed body that verifies and approves investment proposals through a fast-track online endorsement system created under Myanmar’s 2017 Myanmar Investment Law. Designed to speed up foreign and domestic investment without requiring formal approval, the law was implemented with consultation from the World Bank and Japanese officials in April 2017, just before the August “clearance” operations began. “Liberalization of Myanmar’s investment law has been a priority across the political spectrum,” the World Bank reported at the time23.

India and Myanmar’s Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport Project aims to link Sittwe Port with Kolkata, West Bengal.

The opening of Rakhine’s free-market economy includes other planned investments. Maps in the Rakhine State Investment Opportunity Survey show oil and gas fields divided into 13 sections covering the entire 700-kilometre Rakhine coast. Also up for grabs is the land where the IDP camps are located—three maps in the survey show that the area is slated for potential investment in manufacturing, fisheries, and tourism24.

In response to media coverage of the genocide against the Rohingya, international investment continues to grow, albeit at a slower pace25. In February 2019, 108 potential investors were invited to the Rakhine State Investment Fair and asked to indicate what business sectors they were interested in. Of the unnamed companies, 44 were from Myanmar, 25 from Japan and 14 from China, followed by five from Italy and four from Korea. In smaller numbers were the US, Australia, France, Germany, Ireland, Malaysia and the UK. Of the 108 potential investors, 37 said they wanted to invest in hotels and tourism26.

Vicky Bowman, director of the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, said companies can ensure their business in Myanmar is ethical by doing their due diligence regarding human rights (see sidebar). She says it is ethical to apply for an MIC permit because MIC is part of the civilian administration rather than the Tatmadaw, and implements the Myanmar Investment Law.

Thinking of investors flying over the Rohingya incarcerated in the IDP camps, I asked Ms. Bowman if she thought, considering the human rights abuses committed against the Rohingya, if any investment in Rakhine could be considered ethical. “Rakhine is a large, long state. While Northern and Central Rakhine State are conflict areas which responsible investors are generally avoiding, Southern Rakhine [Kyaukphyu, Ngapali] is generally not affected by conflict. However, as anywhere, human rights due diligence is necessary.”

When asked about the property developments in Sittwe, prominent Rohingya activist and Boycott Myanmar campaign founder Nay San Lwin, who lives in Germany, said, “The companies don’t care that people are suffering. They just want the business.” Like the IOM official, he believes the Rohingya in the IDP camps will never be allowed to return to their land. Rather than being granted citizenship and freedom, they will only be moved to different camps. “For these reasons, we started the campaign to pressure companies from investing.”

Britain’s Colonial Land Grab

When General Min Aung Hlaing referred to “unfinished business” in his Sittwe speech, he may well have been referring to Rakhine’s colonial history.

When the British colonized Burma (Myanmar) in 1824, they treated it administratively as part of India, employing Indian migrants in the colonial civil service while providing little support to the Buddhist religious hierarchy. This caused much aggravation and anti-British sentiment, as well as resentment towards Burma’s ethnic minorities who were pro-British, including Rohingya Muslims and the Christian Karen27.

During the Second World War, loyalties became further divided along ethnic and religious lines when the Rohingya supported the British while the Buddhist Bamar majority—the group to which State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi belongs—supported the invasion of the Japanese, at least initially until the Japanese proved to be more violent than the British. In 1942, on orders from Arakan leaders when the British were forced to withdraw from the state, 307 Muslim villages were destroyed, 100,000 Rohingya were massacred and 80,000 fled to refugee camps across the border to what is now modern Bangladesh28. In return for their loyalty and sacrifice, the British offered the Rohingya their own Muslim National Area, but once the Japanese were defeated the British reneged on their promise, leaving the Rohingya to fend for themselves29.

In pre-colonial times, the borders of Arakan (Rakhine) were porous, regularly expanding and contracting as far west as Bengal—natural, given their close geographical proximity. Evidence shows that as early as 3,000 BC an Indo-Aryan speaking group associated with the Rohingya emigrated to Arakan30. Rohingya Muslims are also well documented to have been part of the independent nation’s patchwork of ethnicities, and up to 1638 AD at least 18 Muslim kings held court in Mrauk U31 before the British designated Sittwe as the capital.

After the British reneged on the Rohingya, leaving them vulnerable to the Buddhist majority, the issue of who lived in Arakan prior to the British annexation in 1824 become a belabored part of the official narrative, including the oft-parroted claim among officials, and locals I spoke with throughout Sittwe, that the Rohingya are “Bengali” Muslim “extremists” and “outsiders.”

General Ne Win filled the vacuum of power left by the British with a military coup in 1962, and during his xenophobic dictatorship forcibly deported thousands of Indian migrants. Then, in an effort to detract from the country’s economic crisis in 1974, he imposed the Emergency Immigration Act, requiring ethnically based identity cards and making the Rohingya eligible only for Foreign Registration Cards—thus instigating another exodus of Rohingya into Bangladesh around 197832. The discriminatory 1982 Citizenship Law followed, granting full citizenship only to ethnic groups deemed “indigenous,” such as Bamars and Rakhines, while denying the Rohingya full citizenship based on their ethnicity, effectively making them stateless33.

The colonial legacy of the British has had other far-reaching effects on modern Myanmar. It was the British who founded the Burmese police force, and today top positions are still staffed by the military—so the police who either did nothing, or assisted the mobs in burning Arif’s home and killing his neighbour, must have had orders from above. The use of forced labour among the Rohingya and other ethnic groups to build roads, infrastructure and even hotels for tourists, is based on the British colonial 1907 Town Act and 1908 Village Act, which entitle the headman or policemen of towns and villages to demand that residents assist the government34.

Yangon’s notorious Insein Prison, where journalists, artists, and political dissidents are routinely imprisoned, was designed by the British. In 2018, Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo spent more than 500 days in Insein for their ground-breaking reporting on the killings of 10 Rohingya men in the coastal Rakhine village of Inn Din—the first time that the perpetrators admitted their involvement in the killing of Rohingya35. Inn Din was destroyed in a similar way to Pike Thae—burned to the ground and the land scraped clean of evidence, except in the case of Inn Din, security infrastructure was built over top of it36. The arrest of the journalists was based on the charge that they had obtained confidential documents in breach of the Official Secrets Act, which dates back to colonial British rule. They were later released under international pressure in May 2019.

Tatmadaw Businesses Exposed

Soon after the release of the Reuters journalists, the United Nations Human Rights Council caused an international sensation in August 2019 when it released a report based on its fact-finding mission in Myanmar, exposing for the first time the military’s business ties and establishing in detail how the Tatmadaw has used its own businesses, foreign companies and arms deals to support its brutal operations, which constitute crimes under international law37.

The report identified Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and Deputy Commander-in-Chief Vice Senior General Soe Win as the top military leaders involved in various industries, from arms deals to banking, property development and tourism. Both generals head the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) and Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL), umbrella organizations that cast a wide shadow over multiple business dealings throughout Myanmar. While the MEC is involved in gem production, banking, tourism, and transport, MEHL is involved in mining, manufacturing, telecommunications, and natural resources.

The report named at least 14 foreign companies from China, North Korea, India, Israel, the Philippines, Russia, and the Ukraine that have supplied fighter jets, armored combat vehicles, warships, missiles and missile launchers to Myanmar since 2016, as well as 15 foreign firms involved in joint ventures with the MEC and MEHL, and 44 others with commercial ties to them.

“Foreign companies with joint ventures and other commercial relationships with the Tatmadaw, Myanmar business donors to the Tatmadaw’s operations, and arms suppliers are in some cases legally implicated in the conduct of the Tatmadaw, and in all cases complicit through their tacit acceptance and approval of the Tatmadaw’s actions,” the report said. “This conclusion is most notable in northern Rakhine, where private businesses are assisting the implementation of the inhumane and discriminatory policies of the Tatmadaw specifically and the government as a whole under the guise of economic development and reconstruction.”

Myanmar’s economic policy is closely linked Tatmadaw’s “four cuts” counterinsurgency strategy, which aims to cut access to food, funds, intelligence, and recruits from groups such as ARSA (the Rohingya insurgent group) and the AA38. While the Tatmadaw’s strategy applies both groups, it has made no distinction between ARSA, now largely inactive, and the vast majority of innocent Rohingya civilians, which it collectively demonizes as terrorists.

The Mission called for an arms embargo and said the UN Security Council and member states should impose targeted sanctions against companies run by the Tatmadaw. It also encouraged consumers, investors, and firms at home and abroad to engage with businesses unaffiliated with the military instead.

Searching for Arif’s Home

Off Main Road running parallel to the waterfront, there’s a large multi-storied hotel under construction, a seafood restaurant and a café where the occasional NGO worker takes a coffee break. At the Rakhine State Cultural Museum, the centuries-old history of the Rohingya has been completely excluded from that of Rakhine’s other ethnic groups. On the second floor, the museum’s curtains are drawn to block the view of the Jamia Mosque next door. Built in 185939, the mosque remains partially hidden behind cement walls and guarded by police, its façade blackened by fire, its windows shattered and dark. Across the road behind a children’s playpark, the Kon Dan quarter where Arif once lived is blocked by barbed wire and police checkpoints.

When I visited the area to find out what happened to Arif’s home, the neighborhood surrounding Kon Dan resounded with the sound of construction as new houses were being built and a Buddhist temple underwent renovations. Arif said he had heard that a Chinese company was developing the area, but so far no large commercial construction appeared to be underway, and the neighbourhood appeared to be mostly Hindu, with hundreds of people out on the streets.

Inside a Hindu temple, one alcove held a statue of Kali, the black goddess of destruction, while in another, Durga, the goddess of war, brandished a weapon in each of her many arms, destroying a man with the aid of a lion. “A demon,” the caretaker explained. The scenario seemed a poignant description of the Rohingya now demonized and missing from the neighbourhood.

GPS coordinates showed that Arif’s land was on the other side of the blockade. Next to the police checkpoint, a middle-aged woman with long hair called out from under a shop awning. She pointed at the road beyond the barbed wire. “No Muslim! Rakhine. Hindu. No Muslim!”

A group of Rhakine and Hindu women gathered under the awning. Among them was a slim young woman wearing a bindi on her forehead and thanaka on her cheeks—a yellow powder ground from tree bark often worn in Myanmar to protect the skin from the sun. When she saw me she rubbed her fingers and touched them to her lips; she wanted money for food.

Beyond the blockade, dust whirled up from the street in the glaring afternoon sun. Police were absent from the checkpoint. It appears that fewer officers have been manning their checkpoints since January 2019, when the AA killed 13 police officers in targeted attacks in Buthidaung, following up with more targeted attacks on police around the state and a rocket attack on a Myanmar Navy tugboat in Sittwe that killed two security personnel later that June40.

At Kon Dan’s eastern checkpoint, the police may have been absent, but the blockade was still closely guarded. As I approached, a local man with a checkered longyi wrapped around his waist sternly blocked the way, and so what happened to Arif’s house would have to remain a mystery. Watching from the shade of the awning, the Hindu woman who had asked me for money made a sharp slicing gesture across her neck and stuck out her tongue. The other women laughed.

“Enemy” Territory

To see how the Rohingya are living under apartheid conditions, I went to visit Fajar Alam, the uncle of a young Rohingya refugee I had met in 2016 when visiting the refugee camps in Aceh, Indonesia, almost a year after fishermen had rescued 1,800 Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi migrants whose boat had sunk off the Acehnese coast.

Fajar lives in Say Tha Ma Gyi, just outside the IDP camp where Arif is incarcerated. Fajar and his family had watched from their house as Arif, his family, and thousands of other Rohingya were marched past on the dusty, broken road to the camp.

Along the road to Say Tha Ma Gyi is Bumay, the Muslim quarter where an estimated 2,000 Rohingya have lived on the outskirts of Sittwe since before the 2012 violence. Because they were relatively far from where the violence took place, their houses were spared. Still, police barricades confine them between Sittwe and the IDP camps, creating ghetto-like conditions.

An estimated 2,000 Rohingya live in ghettoized conditions, unable to leave Sittwe’s Bumay quarter near the IDP camps.

It took me several hours to procure a pedicab to the meeting point with Fajar in Bumay, as one Rakhine driver after another emphatically refused to enter for fear being mobbed in “enemy” territory. “They all work together,” one Rakhine local had told me with conviction. “If I walked into a Muslim village, they would kill me.”

Finally Aung Tun, a driver in his early 20s, agreed to take me to Say Tha Ma Gyi, for a steep price.

Aung Tun’s pedicab puttered feebly as the three-wheeled vehicle dipped in and out of potholes past Sittwe University, now heavily guarded and surrounded by razor wire. We passed herds of cattle, dusty street markets, fish stretched and hung to dry in the sun, a woman in chador holding her sequined umbrella aloft, and fields of rice, golden and ready to harvest, stretching over the plain that might one day become hotels and resorts, or a manufacturing zone.

An hour later, we reached the meeting point where Fajar, 23, was waiting. Rohingya men gathered round the pedicab, peering in. Their bodies looked painfully thin compared to Aung Tun’s sturdy frame. Fajar’s skin stretched tightly over his cheekbones and his arms and legs were like matchsticks, but his smile was wide. Aung Tun scowled and wiped away the sweat pouring down his face. He was agitated but had already agreed to complete a round trip. He didn’t want to wait here among the Rohingya, so he agreed to come to Fajar’s house.

The house was nominally larger than an IDP camp hut. Made of woven bamboo and roofed with corrugated tin, it had a front room with a raised wooden dais for sitting, a kitchen with a simple cast iron stove in the centre, and a room where Fajar’s entire family slept, with nails on the walls for hanging their clothes and holes in the floorboards. Like Arif, Fajar is a high school teacher.

The family spoke proudly of Fajar’s nephew Mahmud who, at 14, had escaped by smuggler’s boat and almost died at sea before he was rescued by the Acehnese fishermen. Now 18, Mahmud has been resettled in the US, where he is in college studying to become an immigration lawyer. “We hope he will remember us when he is successful,” Fajar said.

His three nieces and four nephews range from three years old to 21. Their mother, Noor, was preparing chicken for lunch, waving the freshly plucked bird over a flame on the stove to rid it of excess feathers. A petite woman in a black flowered dress, Noor attempted a weary smile, but her eyes drooped with hardship and fatigue.

“We can’t get what we need because everything is so expensive,” she said. “My children are in school, and it’s costing a lot of money…Life is so hard. My house is broken and I don’t have money to fix it.”

Behind their house, chickens ran in the yard and the huts of Say Tha Ma Gyi hugged the horizon. Somewhere among them lived Arif and his family, whom I would never be able to meet in person. Under Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership, journalists are no longer permitted to enter the camps. Bumay is also restricted, but the security posts were empty that day.

“Please come in. You are welcome in our home,” Fajar told me and Aung Tun, but Aung Tun chose to stay outside and smoke in the yard. Noor cooked rice and water spinach to accompany the chicken, and two of her bright-eyed daughters, wearing matching green dresses, set the food on a table outside. The oldest, Safya, 17, excels at science and says she wants to be a doctor—their father is a skilled medic. But under the current regime she will likely not go beyond high school. As with Arif, her full potential to contribute to her country will be wasted.

Rohingya mother and children in IDP camp near Sittwe.

Source: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operation

Fajar urged Aung Tun to eat until he reluctantly accepted a plate, saying, “I am just a poor man.” Besides Fajar and the youngest, who sat on the kitchen floor with his bowl, the rest of the family did not eat. With his stomach full, Aung Tun began relaxed a little and ventured into the kitchen.

On the way back to Sittwe, Aung Tun admitted it was his first time in the Muslim quarter. Smiling and visibly relieved, he accepted payment for his bravery and puttered off down Main Road, past the police barricades guarding the space where Arif and his family once lived.

Corporations and Human Rights in Myanmar

All business enterprises active in Myanmar or trading with or investing in businesses in Myanmar should demonstrably ensure that their operations are compliant with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. They should respect human rights, avoiding infringing on the human rights of others and addressing the adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved. They should have:

- a policy commitment to meet their responsibility to respect human rights;

- a human rights due diligence process to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their impacts on human rights;

- processes to enable the remediation of any adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute.

NOTES:

- Francis Wade, Myanmar’s Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim “Other.” London: Zed Books, 2017.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/FFM-Myanmar/A_HRC_39_64.docx

- reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-segregation-insight/we-cant-go-anywhere-myanmar-closes-rohingya-camps-but-entrenches-segregation-idUSKBN1O502U

- bbc.com/news/world-asia-41160679

- aljazeera.com/news/2017/08/deadly-clashes-erupt-myanmar-restive-rakhine-state-170825055848004.html

- researchgate.net/publication/326912213_Forced_Migration_of_Rohingya_The_Untold_Experience

- unicef.org/myanmar/rakhine-state

- Azeem Ibrahim, The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2016.

- dica.gov.mm/sites/dica.gov.mm/files/news-files/report_on_rsios_for_printing_20190215_english.pdf

- amnesty.org/en/documents/asa16/0417/2019/en/

- weforum.org/agenda/2016/04/worlds-fastest-growing-economies/

- mmtimes.com/news/rakhine-opens-new-beaches-hotel-tourism-investments.html

- http://themimu.info/emergencies/rakhine

- rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/icpvtr/arakan-army-myanmars-new-front-of-conflict/

- Francis Wade, Myanmar’s Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim “Other.” London: Zed Books, 2017.

- Azeem Ibrahim, The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2016.

- https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/docs/42/4248317_-os-myanmar-india-mil-construction-of-indian-port-harms.html

- irrawaddy.com/business/10m-land-reclamation-project-restive-rakhine-readies-sales.html

- imyanmarhouse.com/en/project/20772/real-estate-agencies?en=true

- worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/01/25/new-investment-law-helps-myanmar-rebuild-its-economy-and-create-jobs

- dica.gov.mm/sites/dica.gov.mm/files/news-files/report_on_rsios_for_printing_20190215_english.pdf

- imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2019/04/10/Myanmar-2018-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-the-46748

- dica.gov.mm/sites/dica.gov.mm/files/news-files/report_on_rsios_for_printing_20190215_english.pdf

- Azeem Ibrahim, The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2016.

- /R. Bischoff, Buddhism in Myanmar: A Short History. 1996.

- SIL 2015. Languages of Myanmar: Ethnologue Country Report. Dallas, Texas, SIL.

- A. Berlie, The Burmanization of Myanmar’s Muslims. Bangkok: White Lotus, 2008.

- tni.org/en/publication/arakan-rakhine-state

- Azeem Ibrahim, The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2016.

- Emma Larkin, Finding George Orwell in Burma. London: Granta Books, 2011.

- https://uk.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/myanmar-rakhine-events/

- amnesty.org/en/documents/asa16/0417/2019/en/

- https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/MyanmarFFM/Pages/EconomicInterestsMyanmarMilitary.aspx

- Emma Larkin, Finding George Orwell in Burma. London: Granta Books, 2011.

- A. Berlie, The Burmanization of Myanmar’s Muslims. Bangkok: White Lotus, 2008.

- rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/icpvtr/arakan-army-myanmars-new-front-of-conflict/

_______________________________________________

NOTE: Physical descriptions and names have been omitted or changed for security reasons.

Source: 2018 UN Report, Independent Fact-Finding Mission in Myanmar

Go to Original – investigativejournal.org

Tags: Asia, Aung San Suu Kyi, Bangladesh, Buddhism, Burma/Myanmar, Cultural violence, Direct violence, Ethnic Cleansing, Genocide, History, Human Rights, International Court of Justice ICJ, Justice, Maung Zarni, Racism, Religion, Rohingya, Social justice, Structural violence, United Nations

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ASIA-UPDATES ON MYANMAR ROHINGYA GENOCIDE: