How the Pandemic Defeated the USA

ANGLO AMERICA, 10 Aug 2020

Ed Yong | The Atlantic - TRANSCEND Media Service

A virus has brought the world’s most powerful country to its knees.

4 Aug 2020 – How did it come to this? A virus a thousand times smaller than a dust mote has humbled and humiliated the planet’s most powerful nation. America has failed to protect its people, leaving them with illness and financial ruin. It has lost its status as a global leader. It has careened between inaction and ineptitude. The breadth and magnitude of its errors are difficult, in the moment, to truly fathom.

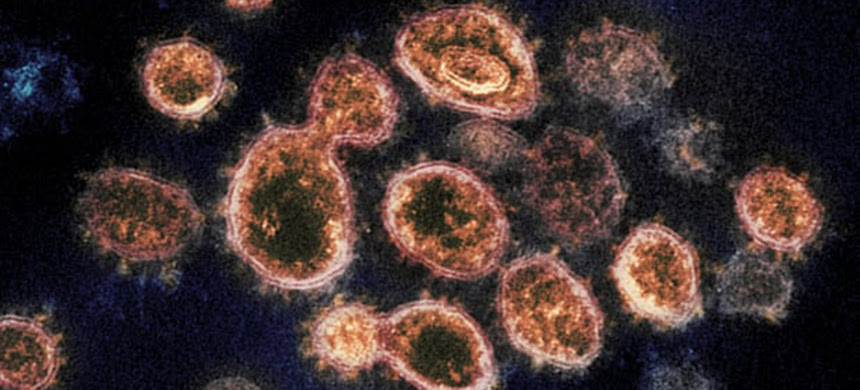

A pandemic can be prevented in two ways: Stop an infection from ever arising, or stop an infection from becoming thousands more. The first way is likely impossible. There are simply too many viruses and too many animals that harbor them. Bats alone could host thousands of unknown coronaviruses; in some Chinese caves, one out of every 20 bats is infected. Many people live near these caves, shelter in them, or collect guano from them for fertilizer. Thousands of bats also fly over these people’s villages and roost in their homes, creating opportunities for the bats’ viral stowaways to spill over into human hosts. Based on antibody testing in rural parts of China, Peter Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit that studies emerging diseases, estimates that such viruses infect a substantial number of people every year. “Most infected people don’t know about it, and most of the viruses aren’t transmissible,” Daszak says. But it takes just one transmissible virus to start a pandemic.

As the coronavirus established itself in the U.S., it found a nation through which it could spread easily, without being detected. For years, Pardis Sabeti, a virologist at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, has been trying to create a surveillance network that would allow hospitals in every major U.S. city to quickly track new viruses through genetic sequencing. Had that network existed, once Chinese scientists published SARS‑CoV‑2’s genome on January 11, every American hospital would have been able to develop its own diagnostic test in preparation for the virus’s arrival. “I spent a lot of time trying to convince many funders to fund it,” Sabeti told me. “I never got anywhere.”

Water running along a pavement will readily seep into every crack; so, too, did the unchecked coronavirus seep into every fault line in the modern world. Consider our buildings. In response to the global energy crisis of the 1970s, architects made structures more energy-efficient by sealing them off from outdoor air, reducing ventilation rates. Pollutants and pathogens built up indoors, “ushering in the era of ‘sick buildings,’ ” says Joseph Allen, who studies environmental health at Harvard’s T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Energy efficiency is a pillar of modern climate policy, but there are ways to achieve it without sacrificing well-being. “We lost our way over the years and stopped designing buildings for people,” Allen says.

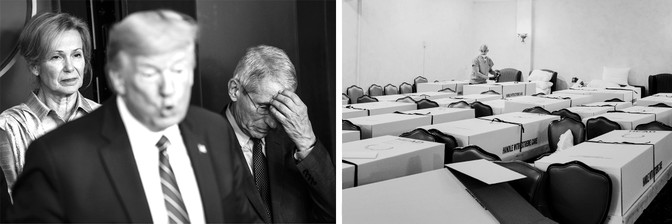

(Rose Marie Cromwell; Tim Rue / Bloomberg / Getty)

Other densely packed facilities were also besieged. America’s nursing homes and long-term-care facilities house less than 1 percent of its people, but as of mid-June, they accounted for 40 percent of its coronavirus deaths. More than 50,000 residents and staff have died. At least 250,000 more have been infected. These grim figures are a reflection not just of the greater harms that COVID‑19 inflicts upon elderly physiology, but also of the care the elderly receive. Before the pandemic, three in four nursing homes were understaffed, and four in five had recently been cited for failures in infection control. The Trump administration’s policies have exacerbated the problem by reducing the influx of immigrants, who make up a quarter of long-term caregivers.

Even though a Seattle nursing home was one of the first COVID‑19 hot spots in the U.S., similar facilities weren’t provided with tests and protective equipment. Rather than girding these facilities against the pandemic, the Department of Health and Human Services paused nursing-home inspections in March, passing the buck to the states. Some nursing homes avoided the virus because their owners immediately stopped visitations, or paid caregivers to live on-site. But in others, staff stopped working, scared about infecting their charges or becoming infected themselves. In some cases, residents had to be evacuated because no one showed up to care for them.

America’s neglect of nursing homes and prisons, its sick buildings, and its botched deployment of tests are all indicative of its problematic attitude toward health: “Get hospitals ready and wait for sick people to show,” as Sheila Davis, the CEO of the nonprofit Partners in Health, puts it. “Especially in the beginning, we catered our entire [COVID‑19] response to the 20 percent of people who required hospitalization, rather than preventing transmission in the community.” The latter is the job of the public-health system, which prevents sickness in populations instead of merely treating it in individuals. That system pairs uneasily with a national temperament that views health as a matter of personal responsibility rather than a collective good.

Ripping unimpeded through American communities, the coronavirus created thousands of sickly hosts that it then rode into America’s hospitals. It should have found facilities armed with state-of-the-art medical technologies, detailed pandemic plans, and ample supplies of protective equipment and life-saving medicines. Instead, it found a brittle system in danger of collapse.

American hospitals operate on a just-in-time economy. They acquire the goods they need in the moment through labyrinthine supply chains that wrap around the world in tangled lines, from countries with cheap labor to richer nations like the U.S. The lines are invisible until they snap. About half of the world’s face masks, for example, are made in China, some of them in Hubei province. When that region became the pandemic epicenter, the mask supply shriveled just as global demand spiked. The Trump administration turned to a larder of medical supplies called the Strategic National Stockpile, only to find that the 100 million respirators and masks that had been dispersed during the 2009 flu pandemic were never replaced. Just 13 million respirators were left.

In April, four in five frontline nurses said they didn’t have enough protective equipment. Some solicited donations from the public, or navigated a morass of back-alley deals and internet scams. Others fashioned their own surgical masks from bandannas and gowns from garbage bags. The supply of nasopharyngeal swabs that are used in every diagnostic test also ran low, because one of the largest manufacturers is based in Lombardy, Italy—initially the COVID‑19 capital of Europe. About 40 percent of critical-care drugs, including antibiotics and painkillers, became scarce because they depend on manufacturing lines that begin in China and India. Once a vaccine is ready, there might not be enough vials to put it in, because of the long-running global shortage of medical-grade glass—literally, a bottle-neck bottleneck.

(Sarah Blesener; Alexis Hunley)

The coronavirus found, exploited, and widened every inequity that the U.S. had to offer. Elderly people, already pushed to the fringes of society, were treated as acceptable losses. Women were more likely to lose jobs than men, and also shouldered extra burdens of child care and domestic work, while facing rising rates of domestic violence. In half of the states, people with dementia and intellectual disabilities faced policies that threatened to deny them access to lifesaving ventilators. Thousands of people endured months of COVID‑19 symptoms that resembled those of chronic postviral illnesses, only to be told that their devastating symptoms were in their head. Latinos were three times as likely to be infected as white people. Asian Americans faced racist abuse. Far from being a “great equalizer,” the pandemic fell unevenly upon the U.S., taking advantage of injustices that had been brewing throughout the nation’s history.

Of the 3.1 million Americans who still cannot afford health insurance in states where Medicaid has not been expanded, more than half are people of color, and 30 percent are Black.* This is no accident. In the decades after the Civil War, the white leaders of former slave states deliberately withheld health care from Black Americans, apportioning medicine more according to the logic of Jim Crow than Hippocrates. They built hospitals away from Black communities, segregated Black patients into separate wings, and blocked Black students from medical school. In the 20th century, they helped construct America’s system of private, employer-based insurance, which has kept many Black people from receiving adequate medical treatment. They fought every attempt to improve Black people’s access to health care, from the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in the ’60s to the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010.

A number of former slave states also have among the lowest investments in public health, the lowest quality of medical care, the highest proportions of Black citizens, and the greatest racial divides in health outcomes. As the COVID‑19 pandemic wore on, they were among the quickest to lift social-distancing restrictions and reexpose their citizens to the coronavirus. The harms of these moves were unduly foisted upon the poor and the Black.

As of early July, one in every 1,450 Black Americans had died from COVID‑19—a rate more than twice that of white Americans. That figure is both tragic and wholly expected given the mountain of medical disadvantages that Black people face. Compared with white people, they die three years younger. Three times as many Black mothers die during pregnancy. Black people have higher rates of chronic illnesses that predispose them to fatal cases of COVID‑19. When they go to hospitals, they’re less likely to be treated. The care they do receive tends to be poorer. Aware of these biases, Black people are hesitant to seek aid for COVID‑19 symptoms and then show up at hospitals in sicker states. “One of my patients said, ‘I don’t want to go to the hospital, because they’re not going to treat me well,’ ” says Uché Blackstock, an emergency physician and the founder of Advancing Health Equity, a nonprofit that fights bias and racism in health care. “Another whispered to me, ‘I’m so relieved you’re Black. I just want to make sure I’m listened to.’ ”

Black people were both more worried about the pandemic and more likely to be infected by it. The dismantling of America’s social safety net left Black people with less income and higher unemployment. They make up a disproportionate share of the low-paid “essential workers” who were expected to staff grocery stores and warehouses, clean buildings, and deliver mail while the pandemic raged around them. Earning hourly wages without paid sick leave, they couldn’t afford to miss shifts even when symptomatic. They faced risky commutes on crowded public transportation while more privileged people teleworked from the safety of isolation. “There’s nothing about Blackness that makes you more prone to COVID,” says Nicolette Louissaint, the executive director of Healthcare Ready, a nonprofit that works to strengthen medical supply chains. Instead, existing inequities stack the odds in favor of the virus.

Clear distribution of accurate information is among the most important defenses against an epidemic’s spread. And yet the largely unregulated, social-media-based communications infrastructure of the 21st century almost ensures that misinformation will proliferate fast. “In every outbreak throughout the existence of social media, from Zika to Ebola, conspiratorial communities immediately spread their content about how it’s all caused by some government or pharmaceutical company or Bill Gates,” says Renée DiResta of the Stanford Internet Observatory, who studies the flow of online information. When COVID‑19 arrived, “there was no doubt in my mind that it was coming.”

Sure enough, existing conspiracy theories—George Soros! 5G! Bioweapons!—were repurposed for the pandemic. An infodemic of falsehoods spread alongside the actual virus. Rumors coursed through online platforms that are designed to keep users engaged, even if that means feeding them content that is polarizing or untrue. In a national crisis, when people need to act in concert, this is calamitous. “The social internet as a system is broken,” DiResta told me, and its faults are readily abused.

(Mark Peterson / Redux; Amy Lombard)

Beginning on April 16, DiResta’s team noticed growing online chatter about Judy Mikovits, a discredited researcher turned anti-vaccination champion. Posts and videos cast Mikovits as a whistleblower who claimed that the new coronavirus was made in a lab and described Anthony Fauci of the White House’s coronavirus task force as her nemesis. Ironically, this conspiracy theory was nested inside a larger conspiracy—part of an orchestrated PR campaign by an anti-vaxxer and QAnon fan with the explicit goal to “take down Anthony Fauci.” It culminated in a slickly produced video called Plandemic, which was released on May 4. More than 8 million people watched it in a week.

During a pandemic, leaders must rally the public, tell the truth, and speak clearly and consistently. Instead, Trump repeatedly contradicted public-health experts, his scientific advisers, and himself. He said that “nobody ever thought a thing like [the pandemic] could happen” and also that he “felt it was a pandemic long before it was called a pandemic.” Both statements cannot be true at the same time, and in fact neither is true.

A month before his inauguration, I wrote that “the question isn’t whether [Trump will] face a deadly outbreak during his presidency, but when.” Based on his actions as a media personality during the 2014 Ebola outbreak and as a candidate in the 2016 election, I suggested that he would fail at diplomacy, close borders, tweet rashly, spread conspiracy theories, ignore experts, and exhibit reckless self-confidence. And so he did.

No one should be shocked that a liar who has made almost 20,000 false or misleading claims during his presidency would lie about whether the U.S. had the pandemic under control; that a racist who gave birth to birtherism would do little to stop a virus that was disproportionately killing Black people; that a xenophobe who presided over the creation of new immigrant-detention centers would order meatpacking plants with a substantial immigrant workforce to remain open; that a cruel man devoid of empathy would fail to calm fearful citizens; that a narcissist who cannot stand to be upstaged would refuse to tap the deep well of experts at his disposal; that a scion of nepotism would hand control of a shadow coronavirus task force to his unqualified son-in-law; that an armchair polymath would claim to have a “natural ability” at medicine and display it by wondering out loud about the curative potential of injecting disinfectant; that an egotist incapable of admitting failure would try to distract from his greatest one by blaming China, defunding the WHO, and promoting miracle drugs; or that a president who has been shielded by his party from any shred of accountability would say, when asked about the lack of testing, “I don’t take any responsibility at all.”

(Al Bello / Getty; Andrew Renneisen / The New York Times / Redux)

Trump is a comorbidity of the COVID‑19 pandemic. He isn’t solely responsible for America’s fiasco, but he is central to it. A pandemic demands the coordinated efforts of dozens of agencies. “In the best circumstances, it’s hard to make the bureaucracy move quickly,” Ron Klain said. “It moves if the president stands on a table and says, ‘Move quickly.’ But it really doesn’t move if he’s sitting at his desk saying it’s not a big deal.”

In the early days of Trump’s presidency, many believed that America’s institutions would check his excesses. They have, in part, but Trump has also corrupted them. The CDC is but his latest victim. On February 25, the agency’s respiratory-disease chief, Nancy Messonnier, shocked people by raising the possibility of school closures and saying that “disruption to everyday life might be severe.” Trump was reportedly enraged. In response, he seems to have benched the entire agency. The CDC led the way in every recent domestic disease outbreak and has been the inspiration and template for public-health agencies around the world. But during the three months when some 2 million Americans contracted COVID‑19 and the death toll topped 100,000, the agency didn’t hold a single press conference. Its detailed guidelines on reopening the country were shelved for a month while the White House released its own uselessly vague plan.

Again, everyday Americans did more than the White House. By voluntarily agreeing to months of social distancing, they bought the country time, at substantial cost to their financial and mental well-being. Their sacrifice came with an implicit social contract—that the government would use the valuable time to mobilize an extraordinary, energetic effort to suppress the virus, as did the likes of Germany and Singapore. But the government did not, to the bafflement of health experts. “There are instances in history where humanity has really moved mountains to defeat infectious diseases,” says Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “It’s appalling that we in the U.S. have not summoned that energy around COVID‑19.”

Instead, the U.S. sleepwalked into the worst possible scenario: People suffered all the debilitating effects of a lockdown with few of the benefits. Most states felt compelled to reopen without accruing enough tests or contact tracers. In April and May, the nation was stuck on a terrible plateau, averaging 20,000 to 30,000 new cases every day. In June, the plateau again became an upward slope, soaring to record-breaking heights.

Trump never rallied the country. Despite declaring himself a “wartime president,” he merely presided over a culture war, turning public health into yet another politicized cage match. Abetted by supporters in the conservative media, he framed measures that protect against the virus, from masks to social distancing, as liberal and anti-American. Armed anti-lockdown protesters demonstrated at government buildings while Trump egged them on, urging them to “LIBERATE” Minnesota, Michigan, and Virginia. Several public-health officials left their jobs over harassment and threats.

It is no coincidence that other powerful nations that elected populist leaders—Brazil, Russia, India, and the United Kingdom—also fumbled their response to COVID‑19. “When you have people elected based on undermining trust in the government, what happens when trust is what you need the most?” says Sarah Dalglish of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who studies the political determinants of health.

“Trump is president,” she says. “How could it go well?”

The countries that fared better against COVID‑19 didn’t follow a universal playbook. Many used masks widely; New Zealand didn’t. Many tested extensively; Japan didn’t. Many had science-minded leaders who acted early; Hong Kong didn’t—instead, a grassroots movement compensated for a lax government. Many were small islands; not large and continental Germany. Each nation succeeded because it did enough things right.

Meanwhile, the United States underperformed across the board, and its errors compounded. The dearth of tests allowed unconfirmed cases to create still more cases, which flooded the hospitals, which ran out of masks, which are necessary to limit the virus’s spread. Twitter amplified Trump’s misleading messages, which raised fear and anxiety among people, which led them to spend more time scouring for information on Twitter. Even seasoned health experts underestimated these compounded risks. Yes, having Trump at the helm during a pandemic was worrying, but it was tempting to think that national wealth and technological superiority would save America. “We are a rich country, and we think we can stop any infectious disease because of that,” says Michael Osterholm, the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “But dollar bills alone are no match against a virus.”

Public-health experts talk wearily about the panic-neglect cycle, in which outbreaks trigger waves of attention and funding that quickly dissipate once the diseases recede. This time around, the U.S. is already flirting with neglect, before the panic phase is over. The virus was never beaten in the spring, but many people, including Trump, pretended that it was. Every state reopened to varying degrees, and many subsequently saw record numbers of cases. After Arizona’s cases started climbing sharply at the end of May, Cara Christ, the director of the state’s health-services department, said, “We are not going to be able to stop the spread. And so we can’t stop living as well.” The virus may beg to differ.

At times, Americans have seemed to collectively surrender to COVID‑19. The White House’s coronavirus task force wound down. Trump resumed holding rallies, and called for less testing, so that official numbers would be rosier. The country behaved like a horror-movie character who believes the danger is over, even though the monster is still at large. The long wait for a vaccine will likely culminate in a predictable way: Many Americans will refuse to get it, and among those who want it, the most vulnerable will be last in line.

Still, there is some reason for hope. Many of the people I interviewed tentatively suggested that the upheaval wrought by COVID‑19 might be so large as to permanently change the nation’s disposition. Experience, after all, sharpens the mind. East Asian states that had lived through the SARS and MERS epidemics reacted quickly when threatened by SARS‑CoV‑2, spurred by a cultural memory of what a fast-moving coronavirus can do. But the U.S. had barely been touched by the major epidemics of past decades (with the exception of the H1N1 flu). In 2019, more Americans were concerned about terrorists and cyberattacks than about outbreaks of exotic diseases. Perhaps they will emerge from this pandemic with immunity both cellular and cultural.

There are also a few signs that Americans are learning important lessons. A June survey showed that 60 to 75 percent of Americans were still practicing social distancing. A partisan gap exists, but it has narrowed. “In public-opinion polling in the U.S., high-60s agreement on anything is an amazing accomplishment,” says Beth Redbird, a sociologist at Northwestern University, who led the survey. Polls in May also showed that most Democrats and Republicans supported mask wearing, and felt it should be mandatory in at least some indoor spaces. It is almost unheard-of for a public-health measure to go from zero to majority acceptance in less than half a year. But pandemics are rare situations when “people are desperate for guidelines and rules,” says Zoë McLaren, a health-policy professor at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County. The closest analogy is pregnancy, she says, which is “a time when women’s lives are changing, and they can absorb a ton of information. A pandemic is similar: People are actually paying attention, and learning.”

Redbird’s survey suggests that Americans indeed sought out new sources of information—and that consumers of news from conservative outlets, in particular, expanded their media diet. People of all political bents became more dissatisfied with the Trump administration. As the economy nose-dived, the health-care system ailed, and the government fumbled, belief in American exceptionalism declined. “Times of big social disruption call into question things we thought were normal and standard,” Redbird told me. “If our institutions fail us here, in what ways are they failing elsewhere?” And whom are they failing the most?

(Brandon Bell; Mel D. Cole)

Americans were in the mood for systemic change. Then, on May 25, George Floyd, who had survived COVID‑19’s assault on his airway, asphyxiated under the crushing pressure of a police officer’s knee. The excruciating video of his killing circulated through communities that were still reeling from the deaths of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, and disproportionate casualties from COVID‑19. America’s simmering outrage came to a boil and spilled into its streets.

Defiant and largely cloaked in masks, protesters turned out in more than 2,000 cities and towns. Support for Black Lives Matter soared: For the first time since its founding in 2013, the movement had majority approval across racial groups. These protests were not about the pandemic, but individual protesters had been primed by months of shocking governmental missteps. Even people who might once have ignored evidence of police brutality recognized yet another broken institution. They could no longer look away.

It is hard to stare directly at the biggest problems of our age. Pandemics, climate change, the sixth extinction of wildlife, food and water shortages—their scope is planetary, and their stakes are overwhelming. We have no choice, though, but to grapple with them. It is now abundantly clear what happens when global disasters collide with historical negligence.

COVID‑19 is an assault on America’s body, and a referendum on the ideas that animate its culture. Recovery is possible, but it demands radical introspection. America would be wise to help reverse the ruination of the natural world, a process that continues to shunt animal diseases into human bodies. It should strive to prevent sickness instead of profiting from it. It should build a health-care system that prizes resilience over brittle efficiency, and an information system that favors light over heat. It should rebuild its international alliances, its social safety net, and its trust in empiricism. It should address the health inequities that flow from its history. Not least, it should elect leaders with sound judgment, high character, and respect for science, logic, and reason.

The pandemic has been both tragedy and teacher. Its very etymology offers a clue about what is at stake in the greatest challenges of the future, and what is needed to address them. Pandemic. Pan and demos. All people.

_________________________________________________

* This article has been updated to clarify why 3.1 million Americans still cannot afford health insurance.

** This article originally mischaracterized similarities between two studies that were retracted in June, one in The Lancet and one in the New England Journal of Medicine. It has been updated to reflect that the latter study was not specifically about hydroxychloroquine.

This article appears in the September 2020 print edition with the headline “Anatomy of an American Failure.”

Ed Yong is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he covers science.

Tags: Anglo America, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Empires, USA

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.