Three Simple Conflict Analysis Tools That Anyone Can Use

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION, 2 Nov 2020

Taylor O’Connor | Medium - TRANSCEND Media Service

To transform conflict in your family, workplace, community, and beyond.

“Peace is not the absence of conflict, but the presence of creative alternatives for responding to conflict.” — Dorothy Thompson

After a week on the job, I learned the following:

- Person A didn’t talk to person B. They had some longstanding personal issues that predated them even working together.

- Person B was the boss, and for her short temper, everyone was afraid of her, except person C, who would lash out whenever he felt person B was overstepping her authority.

- Person C also grossly mistreated his subordinates, but since his only superior (person B) was afraid of him, nothing happened. Most people avoided person C.

- Person D was on the leadership team, but nobody listened to her. She was just a figurehead who held authority, but nobody respected it… Except for ‘Person A,’ of course, who didn’t listen to anyone but ‘person D’ because they were friends.

I thought I had a handle on these dynamics, but the learning continued:

- Person A tried once to organize a secret coup to overthrow the authority of person B, but was foiled by person E, who was an ally of person B (the boss) and acted as an informant when he found out that people were conspiring against her.

- Since person E was person B’s only ally, he had an unofficial authority to micromanage everyone else’s work, even when it had nothing to do with his official job responsibilities. He enjoyed exercising this authority, and most people resented him.

As for some of the others:

- Person F avoided the office almost entirely because she considered it a toxic work environment, and it was wearing on her health.

- Person G avoided conflict, but was passive-aggressive. She would accept what her superiors told her to do; then, she would do the opposite since there was little oversite. Other colleagues had to compensate for her.

- Person H had tried to get everyone to work together at various times, but had long since given up. Person H was also in a secret relationship with Person I, so while he had lost interest in trying to address the myriad conflicts, if some workplace issue affected his partner, he would intervene.

Are you confused yet?

But I didn’t even tell you about person J, K, or L… or the many others. We’re just scratching the surface of this clusterf*uck.

The only thing you might understand from this is that it was a mess. But since you, the reader, are human, chances are you may have encountered a similarly complex conflict scenario at some point in your life. We all have really. And you may wonder how in the world you or anyone could do anything to fix such a mess.

Have no fear; I’m here to help. After some years conducting conflict research, I’ve got a few tricks up my sleeve that might help you find ways to un-fu*k situations like these whenever and wherever you encounter them. We call it conflict transformation.

A few simple truths about conflict:

- Conflicts are everywhere. You’re bound to encounter conflict at one time or another, in the family, in your work, or elsewhere.

- Conflicts tend to grow in complexity and involve more people until issues underlying the conflict get resolved. There is no avoiding this.

- Once a party to a conflict, nobody is neutral. It’s like that book by Howard Zinn: You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.

Now on to the tools. We who study conflict have an array of tools we use to analyze conflict. Not every tool fits any given conflict, but when you understand a few, you can usually pick the right one to help you gain insight into the dynamics of any given conflict. From there, you can find ways to address the problem and ultimately transform the conflict.

The problem here, though, is that these great conflict analysis tools are all super academic and use technical language. They were designed for conflict mediators, researchers, academics, and the like. They aren’t made for regular people.

But I think these tools should be accessible to everyone, to use to transform any conflicts regular people may encounter, be they in your family, in your workplace, in your community, or beyond. So I took a few of my favorite tools that I think are simple and practical for anyone to use, and I have presented them in a user-friendly manner. This means no technical jargon, simplified, and even with some cool sketches a friend of mine did on Canva (free design software). Check them out!

Three Simple Conflict Analysis Tools

1. The Conflict Tree

The conflict tree is a simple and fun tool to help you gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between the causes and effects of a conflict, and to gain clarity about the core of the problem. Often in a conflict, these three things get mixed up, and things get complicated. It is helpful to separate issues and organize them into these categories, then figure out your priorities and make a plan of action to transform the conflict. This is a good tool to help you understand a conflict that is complex.

For groups, this tool can help build consensus about these three components, to facilitate discussion, and to find ways to address the issues.

This tool is also good for those artistically or visually inclined as it includes some drawing and the image of a tree. It can often look quite nice once complete.

How to do it:

- Gather some materials: pens or markers, a big piece of paper like a flip chart paper or something, index cards or sticky notes (or cut smaller pieces of paper). If you’re not working in a group, you could probably do it on a regular-sized piece of paper.

- Draw a picture of a tree, including three sections: the roots, the trunk, and the branches. If in a group, you can ask some artistic person or persons to draw the tree.

- On the small pieces of paper, and individually or as a group, write words and phrases that come to mind when you think of the conflict. This is like a brainstorm. Write anything that describes any issue associated with the conflict: one issue or phrase per paper. There should be many pieces of paper, each representing a different issue/idea.

- The tree branches represent the effects of the conflict, the trunk of the tree represents the core problem (or problems), and the roots of the tree represent the causes of the conflict. Write these words in the appropriate places on the tree (as indicated in the image below), and explain to the group what each section represents.

- Organize the small pieces of paper into these three categories. Move the papers to where they should be: the branches (for effects), the trunk (for core problem), or the roots (for causes). There may be some notes that are repeated or that represent similar ideas. If so, these can be combined. If in a group, there may be lots of discussion until there is full consensus.

- Brainstorm to think if anything is missing to ensure all causes, core problems, and effects are represented on the tree. Add new notes to the tree wherever appropriate.

- Circle which ‘effects’ need to be addressed immediately and which ‘causes’ should be addressed to transform the core problem. Prioritize which actions should be taken.

I’ve facilitated workshops where participants liked their conflict tree so much they recreated it beautifully and displayed it in the office. Below is a photo I took from a workshop nearly ten years ago. This group is in the process of working out their conflict tree.

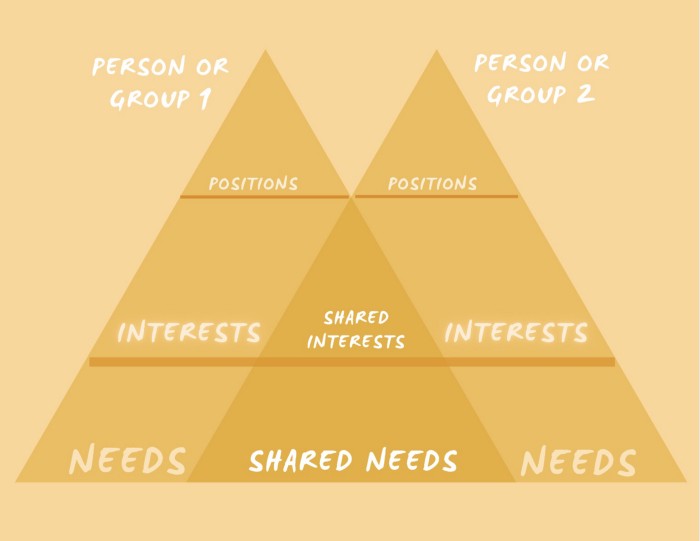

2. The PIN Model

This tool helps persons or groups in conflict find creative solutions to problems by moving away from incompatible positions and focusing on shared interests and needs.

When two persons or groups are in conflict over a particular issue (or course of action), this tool can help identify shared interests and needs. This is a good one for when there is a conflict between two individuals or two groups, so long as the groups in conflict are not divided amongst themselves. You can do it when there are more than two persons or groups, but it is most effective with just two.

It’s actually quite a simple process. All you do is map all of the positions, interests, and needs of each person/group you can think of; then, seek to find where there are shared interests and needs. Putting it into practice, you can try to help the individuals or groups move away from their positions and focus on shared interests and needs.

This activity can be done individually or in groups. I’ll include more detailed steps below:

- Draw two overlapping triangles on a full sheet of paper, as seen in the image below. Write the name of the two persons or groups above each triangle, depending on if the conflict is between two persons or between two groups.

- Map out the positions of each person/group and write them in the top of the triangles of each person/group. These are the positions of each related to the main issue (or issues) of the conflict. There’s a conflict because these positions aren’t compatible. Fill this in on the top of the triangle (as shown in the image below).

- Map out the interests of each person/group that underly their positions. Some interests aren’t compatible with the interests of the other while other interests are shared interests between the two persons/groups. Organize the interests into two categories: 1) shared interests, and 2) individual interests (as indicated in the image below.)

- Map out the needs of each person/group (associated with the conflict). Identify which are shared needs and which are unique needs of each. Fill in the triangles accordingly, shared needs going in the overlapping part of the triangles (as indicated in the image below).

- Put into action by finding ways to get persons/groups in conflict to move away from their positions and to find alternative solutions that focus on shared interests and needs. You can also find creative ways to have individual interests and needs met in ways that help transform the conflict.

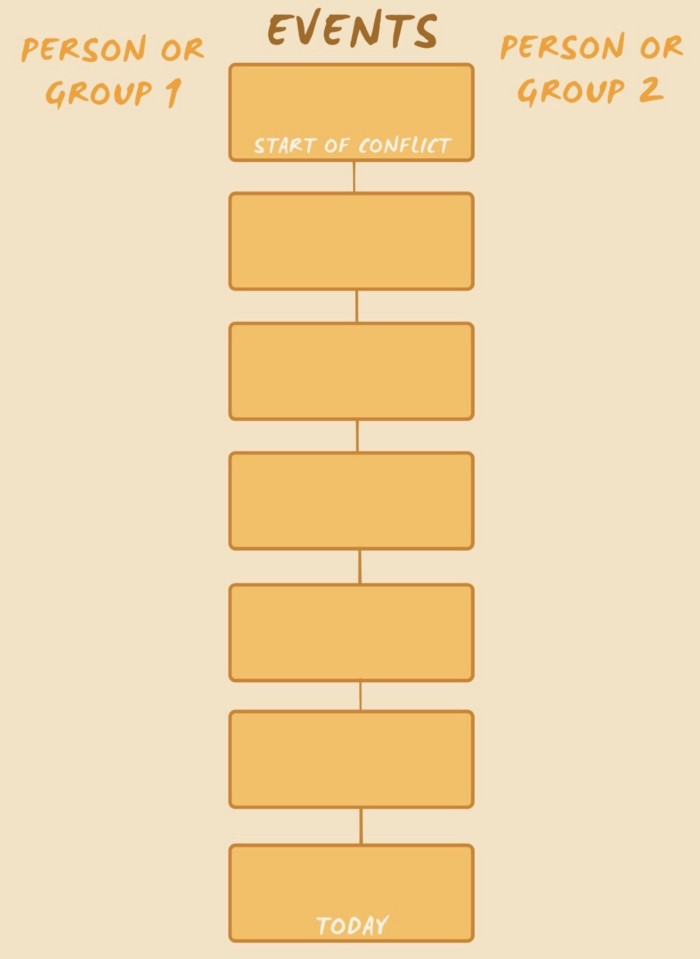

3. The Conflict Timeline

For longstanding conflicts, often, it is helpful to map the course of the conflict. This Conflict Timeline tool can be helpful to understand the history of a conflict from the perspective of different persons or groups involved in the conflict, then to find ways to influence the trajectory in a positive direction. Using this tool, you will create a visual representation of the stages that the conflict has moved through, all the events (both positive and negative) that have influenced conflict dynamics in one way or another, and perspectives from persons/groups on events important to them.

The tool is as it sounds, a graphic plotting of key conflict-related events from the perspective of two persons or groups in conflict. If more than three persons or groups are involved in the conflict, the activity can be expanded to include space for perspectives of each. If done with the participation of persons or groups in conflict, either together or separate, this tool can facilitate greater understanding of the perspectives of each surrounding the conflict history. In itself, it may help parties find ways to move the conflict in a more positive direction.

The process for this tool is as follows:

- Decide who will be involved in this activity. If you have in-depth knowledge of the particular conflict, you may do it individually. As this may be a mapping of conflict between persons or groups, the persons or group representatives may be invited to do this activity together or separately, depending on how tense the conflict dynamics are. Or you may invite persons with in-depth knowledge of the conflict dynamics and an understanding of the perspectives of each person or group.

- Prepare the timeline as a long line on a piece of paper. You can do this on a single sheet or connect some sheets of paper together. In the photo below I used a roll of paper. Prepare the paper(s) as indicated in the sketch below with the events in the middle of the timeline, and the name of each person/group on either side of the timeline (where it’s written ‘person or group A’ and ‘person or group B’). Leave space for the perspectives of each person/group about each event to be written on each side.

- As a group or by yourself, decide when the conflict began and mark this at the beginning of the timeline. Expecting that the conflict is ongoing, the other end of the timeline will be marked as today.

- For this next step, you should use sticky notes or small pieces of paper. Mark or ask the persons/groups to mark in individual sheets of paper each key event in the trajectory of the conflict. These may include the following: a) key events in the early history/stages of the conflict; b) significant events that negatively influenced conflict dynamics; c) key moments of cooperation, where those in conflict worked together or improved on conflict dynamics; or d) missed opportunities for reconciliation or resolution of conflict issues.

- Now arrange these on the timeline in the center in chronological order. You should include as many events as you feel are relevant.

- Now write in, or have participants write in, the significance of each event from the perspective of each person/group on the timeline below the spaces marked ‘person or group A’ and ‘person or group B’.

Apply learning from the timeline:

- Identify differences in perspective about events, and possible gaps in knowledge where one person/group can learn about the other to improve understanding.

- Identify possible recurring events where tensions may be high and/or that may be used to facilitate cooperation or understanding.

- Identify events that promoted cooperation or moved the conflict in a positive direction. Find ways to capitalize on these or make them happen more often.

I hope that in these three tools, you’ve found something interesting that you may use to analyze and ultimately to transform any given conflict that you are interested in addressing. Remember that not every tool is practical for any given conflict. We who analyze conflict have a toolbox of these at our disposal and what we do is select the right tool to analyze any given conflict.

So now you have three conflict analysis tools in your toolbox. I have selected three tools that are quite different so that for whatever conflict you wish to analyze, you should be able to use one or two of these. Then, with the insight you have gained, you can find creative ways to address the conflict. And in the future, whenever you encounter some conflict, you’ll already be prepared with these tools to analyze it and find ways to address it.

After you’ve completed your analysis, if you seek to learn more creative ways to take action to transform the conflict, check out my free downloadable handout with 198 Actions for Peace. I think this will help you generate lots of ideas.

_____________________________________________

Taylor O’Connor, MA Peace Education, UN Mandated University for Peace, 2009. Taylor is a rebellious peacebuilder, peace educator, and founder of the blog Everyday Peacebuilding. Freelance Peacebuilding Technical Specialist by day, he’s working to make insights from peacebuilding practice relevant and practical to wider audiences. If you’d like to learn some creative and strategic ways you can build peace in your life and in the world around you, get his free handout 198 Actions for Peace – also good for educational settings.

Taylor O’Connor, MA Peace Education, UN Mandated University for Peace, 2009. Taylor is a rebellious peacebuilder, peace educator, and founder of the blog Everyday Peacebuilding. Freelance Peacebuilding Technical Specialist by day, he’s working to make insights from peacebuilding practice relevant and practical to wider audiences. If you’d like to learn some creative and strategic ways you can build peace in your life and in the world around you, get his free handout 198 Actions for Peace – also good for educational settings.

Tags: Conflict Analysis, Conflict Transformation, Peace Education

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION: