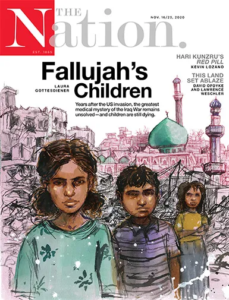

The Children of Fallujah: The Medical Mystery at the Heart of the Iraq War

MILITARISM, 23 Nov 2020

Laura Gottesdiener | The Nation - TRANSCEND Media Service

Since the 2003 invasion, doctors in Fallujah have been reporting a sharp rise in birth defects among the city’s children—and to this day, no one knows why.

9 Nov 2020 – Three years after American soldiers besieged her city, Iraqi pediatrician Samira Alani began to see a problem in the maternity ward. Women were bearing infants with organs spilling out of their abdomens or with their legs fused together like mermaids’ tails. Some looked as if they were covered in snakeskin. Others emerged gasping, unsuccessfully, for air. No one knew what was wrong with the babies, although almost no one was trying to find out, either. It was 2007, the height of the political and sectarian violence unleashed by the US invasion and occupation. Fallujah, where Alani lived and worked, was considered one of the most unstable and inaccessible cities on earth.

The news about the babies spread from the hospital corridors to the inner courtyards of the city’s homes, whispered among female relatives and neighbors. Entisar Hussein, a housewife in Fallujah, learned about the deformities after a cousin returned from the maternity ward. “One woman, she had a child with a tail, and one, she had a child with a rabbit’s face,” Hussein recalled her cousin telling her. The sickness crept into Hussein’s family, too, she said: One of her sisters-in-law delivered an infant without skull bones to protect the brain tissue; the baby died at birth. Another sister-in-law had two miscarriages and then gave birth to a child with an enormous, bloated head. He died, too.

Soon Fallujah’s children became a topic of concern at tribal meetings and in the provincial doctors’ union. Many residents suspected that the major American offensives against the city might have had something to do with the deformities. The second offensive, which began in early November 2004, was the deadliest battle of the entire US war in Iraq—a six-week siege that killed thousands of Iraqis and dozens of Americans and left much of the city in rubble. But these suspicions were kept quiet. Outside people’s homes, just beyond the iron front doors, US Marines patrolled the streets, and residents said they feared the United States wouldn’t respond kindly to insinuations of having sparked a public health crisis. Moreover, the Americans weren’t the only actors that Fallujans had to consider. The Shiite-led national government in Baghdad, which many viewed as a puppet of Washington and Tehran, was engaged in a campaign of arrests, torture, and political retribution against its critics, particularly in Sunni-majority areas like Fallujah. In Fallujah, various Iraqi parties and militias were jockeying for political power, and they, too, sought to control the spread of information for their own agendas.

But even if people hadn’t been afraid, doctors and residents said it didn’t seem there was much anyone could do about the birth defects in those days. All across Iraq, the US invasion had unleashed a wave of violence against doctors, whose relative wealth and high profiles made them easy targets amid the country’s growing sectarian strife. By 2007, when Alani began to notice the birth defects in Fallujah, the Iraqi Medical Association estimated that half of registered doctors had been forced to flee the country. Those who remained, like her, risked not only arrest, kidnapping, and assassination but also the reality of straitened working conditions, brought on by shortages of drugs, medical equipment, and both water and electricity.

“We felt that there was something wrong,” she recalled. “But we could do nothing.”

Alani’s colleague Muntaha Alwani, a fetal medicine specialist, also believed there was a problem. Both women have worked at the hospital since the late 1990s, and they thought they were seeing far more defects than before the US invasion. Alani quietly began to record the cases, and Alwani photographed the tiny patients. Alani made a form to register birth defects and distributed it across the hospital’s wards. Many of their coworkers were skeptical. “Some thought it was of no use,” said Alani. “Of course, they were wrong. Through our documentation, we brought the attention of the whole world.”

Alani’s ad hoc registry was the beginning of a yearslong, unfinished quest to document and investigate the most controversial medical mystery of the Iraq War: an alleged increase in birth defects that, local doctors say, began after the United States invaded the country in 2003 and plagues the city to this day. At stake is the question of whether US military activities in Fallujah contributed to these congenital disorders—an explosive possibility that has transformed this local public health concern into an international political and scientific controversy. For years, the fierce debate over Fallujah has centered on questions about the use and impact of potentially toxic material in US weapons, particularly depleted uranium. The discussion has largely overlooked, however, broader and perhaps even more troubling questions about the long-term public health effects of urban warfare on civilian populations and the dangers of politicizing science and medicine in times of conflict.

The Department of Defense did not respond to most of the questions posed by The Nation about allegations of rising numbers of birth defects in Fallujah resulting from the war. It did share its “Policy for Environmental Remediation Outside the United States,” which states that “DOD has no general authority or funding to engage in environmental remediation outside of the United States.” The policy also states that the Department of Defense “takes no action to remediate environmental contamination resulting from armed conflict.”

For its part, the Iraqi government said the United States has provided invaluable resources in addressing the country’s environmental and health concerns in the years since the invasion. “The United States support[s] us…not only in the field of radiation but also in the field of climate change and the pollution of the water resources,” said Jassim Abdulaziz Humadi Alflahy, Iraq’s deputy minister of health and the environment.

Still, more than 17 years after the US invasion, the mystery of Fallujah’s children continues to haunt Iraq. Nearly every aspect of the story of the city’s birth defects remains contested. And although accounts and images of Fallujah’s maimed and ailing children have traveled from the halls of the World Health Organization and the pages of medical journals to the text of internal Pentagon memos and the posters of anti-war marches, Alani and her colleagues continue to operate in a tiny and underresourced birth defects center, now treating children whose parents were children themselves when the United States invaded Iraq.

On a hot September morning in 2019, more than half a dozen women waited outside a squat building at Fallujah’s maternity hospital on the banks of the Euphrates River. Some sat alone, holding their children or grandchildren on their laps. Others milled around, greeting each other with kisses on the cheek. Among them was Samira Ahmad, who said her infant granddaughter, Maram, had been struggling to breathe since the family took her home from the hospital a few months earlier. She said that Maram is her daughter-in-law’s first child after two previous pregnancies ended in miscarriages. Later that day, the pediatric cardiologist discovered a small hole in Maram’s heart.

Alani, meanwhile, was driving from her house in the center of Fallujah to the hospital. As she drove, she passed clothing stores and vegetable shops, a shiny new burger joint, and roadside tea stands where old men kept watch over boiling kettles and dainty istikan glasses. Late summer is date season in Iraq, and platters piled high with the sweet fruit were perched on nearly every street corner. Scaffolding surrounded some of the famed mosques, whose minarets were punctured with bullet holes.

Alani’s daily commute hadn’t always been this smooth. In 2005 and 2006, after US forces occupied Fallujah, the streets were so choked by US military checkpoints that she had to travel the two miles from her home to the hospital on foot. In early 2014, she anxiously drove past masked fighters with the Islamic State on her way to work. Her home and her hospital have been bombed repeatedly. And yet then, as now, Alani was undeterred.

Shortly after 8 am, Alani parked in front of the birth defects center. A tiny, angular woman, she tilts forward as she walks, giving her the perpetual appearance of being impatient to arrive. She unlocked the clinic and then hurried with short, deliberate steps across the yellowed grass, past the men smoking cigarettes while awaiting news of their wives, and into the neonatal ward, where she bent over a child named Muhammed. He had been born two weeks earlier with a large sac containing part of his brain protruding from the back of his skull, according to a hospital photograph. This defect, called encephalocele, has a high fatality rate, but the doctors on duty said he was recovering from the surgeries that removed the sac and drained the excess spinal fluid.

Alani bent over the incubator, lifting Muhammed’s arms and legs and examining his short neck and misshapen ribs. “He will be crippled,” she said matter-of-factly. He was one of four babies with congenital disorders delivered in the facility on August 28, according to hospital records and interviews with doctors. Two were twins—one with a bloated head and the second with distorted limbs and abnormal genitals. The fourth baby had fully blocked nasal cavities; days earlier, she lay in an incubator next to Muhammed, crying as she struggled to breathe.

Alani cast about the crowded room for Muhammed’s grandmothers, who had stayed by his hospital bedside since his birth. “There are four babies and one, two, three… eight women in here,” Alani muttered to herself with a frown. “It’s not good for the babies.”

Alani has a brusque bedside manner that’s exacerbated by her various pet peeves—too many women crowded into a neonatal ward, doctors who hawk baby formula on behalf of milk companies, and worst of all, colleagues who refuse to participate in her beleaguered birth defects registry. Two decades earlier, she had fallen in love with pediatrics during her medical school training in Baghdad, and she has dedicated her life to the profession ever since. Five days a week, she heads to work in Fallujah’s public hospital, even as friends have fled to the capital or abroad or opted to spend the majority of their time in private practice. Still, after more than 20 years on duty, she occasionally wishes she’d chosen to specialize in dermatology or radiology or anything other than caring for children in a city seemingly plagued by unexplained birth defects.

After examining Muhammed, Alani headed to the hospital’s archives to track down the file for a patient who was born a few days earlier without a skull but whose case hadn’t been recorded in her registry. After some searching, she found the child’s documents amid the bundled stacks of pink, blue, and white sheets of paper. The family was from Abu Ghraib, about 20 miles east of Fallujah and home to the former US prison that became infamous for the torture and sexual abuse that American soldiers carried out behind its walls. She then returned to the birth defects center to examine a child diagnosed with Pierre Robin syndrome, a rare condition in which an infant has an underdeveloped jaw that causes breathing and feeding problems.

“Will she be normal?” asked the child’s grandmother Nahida Sami Aghul. She said it was the second time her daughter had a child with congenital defects; in 2014 she delivered an infant with a shriveled head who died.

“Probably not,” Alani responded flatly, warning that infants with this disorder can die from respiratory problems.

“We’re afraid of the next pregnancy. Can this happen again?” Aghul wondered.

Alani didn’t have an answer, and soon she was summoned back to the neonatal ward to examine a newborn whose spine protruded from a blood-red hole in his back. His mother was still in the delivery room, and she didn’t yet know about the infant’s condition. His grandmother hovered over the incubator and worried aloud about not having the money to pay for the baby’s treatment. Muhammed Namiq, another pediatrician, peeked into the room from the hallway.

“We have many cases like this,” he said.

This was his first year in this hospital, after stints outside Baghdad and in the country’s north and southeast. He said he has seen more birth defects in Fallujah than anywhere else he has worked. He pulled out his phone and showed a picture of an infant born in the hospital that year, according to records from the birth defects clinic. The child had no nose—an extremely rare condition known as arhinia.

Namiq said he performed surgery on the patient, but it didn’t work. The child died after the operation. According to the medical literature, only a few dozen instances of this condition have been recorded worldwide.

Over the past century, veterans and civilians across the world have voiced recurring fears about the health impacts of war on future generations. Conflict has, of course, always posed risks to public health. But the rise of industrialized warfare in the 20th century, with the introduction of chemical weapons and the threat of nuclear attacks, brought new toxic exposures and the possibility of terrifying genetic consequences. In August 1945 the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing more than 200,000 people and thrusting the world into the nuclear age. In the wake of the bombings, “public concern focused more on the genetic consequences than any other untoward health outcome,” observed the geneticist William Schull, a member of the US government’s Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission. “Many individuals had visions of an epidemic of births culminating in misshapen monsters or infants condemned to early death.”

Since then, modern warfare’s potential to deform future generations has sparked unparalleled attention and controversy, even as the science has rarely been conclusive. The largest longitudinal study of Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors and their children was undertaken by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission and its successor, the US-Japanese Radiation Effects Research Foundation. After examining more than 75,000 newborns in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, RERF concluded that “no statistically significant increase in major birth defects or other untoward pregnancy outcomes was seen among children of survivors”—a conclusion reinforced by the agency’s subsequent studies. Despite these findings, the fear of mass genetic distortions sent shock waves through the scientific world and inspired epidemiologists to establish some of the first major registries of congenital disorders.

That fear radiated into the broader population as well. In the decades that followed, US veterans who participated in the Pentagon’s mustard gas experiments during World War II raised concerns about infertility and birth defects among their children. So did veterans sent to the Marshall Islands in the late 1970s to clean up the toxic waste from the Pentagon’s relentless nuclear testing, as well as Marshallese civilians who say the radioactive fallout from 67 nuclear bomb explosions has produced so-called jellyfish babies. In all three cases, the US government does not consider there to be sufficient evidence to link these tests with birth defects.

Then, in the late ’70s, the US public was confronted with prime-time television exposure to these nightmarish visions, as veterans of the Vietnam War began to report birth defects in their children. They blamed the disorders on their wartime contact with the herbicide Agent Orange, which the US Air Force sprayed across swaths of South Vietnam. “We’re not the veterans,” former Green Beret John Woods testified at a 1979 congressional hearing. “Our kids are the veterans.” Meanwhile, the Vietnamese Association for Victims of Agent Orange says as many as 3 million civilians across four generations have suffered from cancers, neural damage, reproductive problems, and other illnesses linked to the toxic chemical. Even now, Vietnamese officials say they are witnessing an increase in the number of children born with birth defects—four decades after the war’s end.

As in the earlier instances, the US government has disputed these claims, arguing “there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of birth defects…resulting from tactical herbicide exposure.” But a number of US and international studies have suggested a link between the chemical and some types of birth defects, helping fuel decades of debate.

Part of the challenge is the complexity of the science. “They [birth defects] are so damn hard to study and to understand and to get causal mechanisms,” said Leslie Roberts, an epidemiologist at Columbia University who has worked with the WHO. “And this makes them uniquely inflammatory and unresolvable. Sometimes we’ll have an issue like Agent Orange where we can actually measure chemical markers of exposure, but usually not.”

Compounding these scientific challenges are the sweeping financial and legal implications of any conclusive evidence. “We have enormously sophisticated propaganda machines that are trying to avoid any liability issues,” said Roberts. In the case of Agent Orange, US veterans sued the chemical companies that manufactured it, including Dow and Monsanto, and won a $180 million settlement in 1984. They also pushed the VA to cover health care for their children born with spina bifida and, in certain instances, a number of other birth defects, even as the agency maintains they are not related to Agent Orange exposure. Meanwhile, US veterans who were exposed to the herbicide and their children, as well as Vietnamese civilians and their descendants, continue to demand additional recognition and compensation for damages.

In 2008 a US court dismissed a class action lawsuit filed on behalf of Vietnamese civilians, after Seth Waxman, who served as solicitor general under Bill Clinton, argued on behalf of the chemical companies that the case could have far-reaching political implications. “This does affect our ongoing diplomacy,” he said. The diplomacy he was referring to was not abstract but was related to a specific conflict that was being fought some 6,000 miles away, with its own controversial weapons: the war in Iraq, during which the US was rumored to have used depleted uranium.

Chemical assault: US planes spray Agent Orange over dense vegetation in South Vietnam in 1966.

TO CONTINUE READING Go to Original – thenation.com

Tags: Anglo America, Arms Industry, Arms Race, Conflict, Geopolitics, Hegemony, History, Human Rights, Imperialism, International Relations, Invasion, Military, Military Industrial Complex, Military Intervention, Military Supremacy, NATO, Occupation, Politics, Power, US Military, USA, Violence, War, War on Terror, West, World

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.