How to Conduct Your Own Conflict Analysis

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION, 7 Dec 2020

Taylor O’Connor | Medium - TRANSCEND Media Service

A User-Friendly Guide

“The key to complexity is finding the elegant beauty of simplicity.”

— John Paul Lederach

1 Dec 2020 – I remember the first conflict analysis I did, some ten or so years ago. I was just getting into consulting in the NGO world, looking to ‘get my foot in the door’ so to speak.

I did well with the CV, and the interview, and the pretending I knew what I was talking about part. Hired. Contracted. Now came the part of figuring out how the hell I was gonna do this thing!

So I downloaded a bunch of PDF guides for conducting conflict analyses. Each was massive, like 100+ pages sometimes! Each had their own approach and came with their own unique set of technical terms. And in the end I came up with a report as massive, complex, and confusing as the guides I was following.

I went on to conduct more conflict analyses, for different organizations, each for different purposes, using different frameworks, approaches, and terminology. I feel like it’s just too easy to overcomplicate things. But to really come up with an analysis that will be of practical use for me, you, or anybody, it’s got to be simple and clear.

Making conflict analysis simple

I figure there are many people and groups out there who are working to transform violent conflict, uproot some injustice, or address some social issue. It’s challenging work! And I know from experience that putting together a nice, clear conflict analysis can be incredibly useful to find strategic, effective ways to transform the issues you’re engaging with.

You’ll find the guides out there on conflict analysis are overly complicated and likely not useful for you. To make things easy on you so that you can produce an easy, effective conflict analysis, I’ve made this little guide for you. In it, I’ve distilled what I’ve learned from conducting numerous conflict analyses over the past ten years. I’ve picked out what works (and left out what doesn’t) from a cross-section of existing frameworks and guides. And I’ve simplified the language.

You may use this guide to conduct a conflict analysis of any conflict, from the local to the national or international levels. It helps to focus on a specific conflict (i.e., anti-Muslim riots in Myanmar) or theme (i.e., police violence in the United States).

When you conduct a conflict analysis, you produce a conflict analysis report. And you can use the report to develop strategies to build peace. So let’s look at what goes into your conflict analysis report. Then I’ll give you some simple steps you can take to conduct your own conflict research (to produce your conflict analysis report).

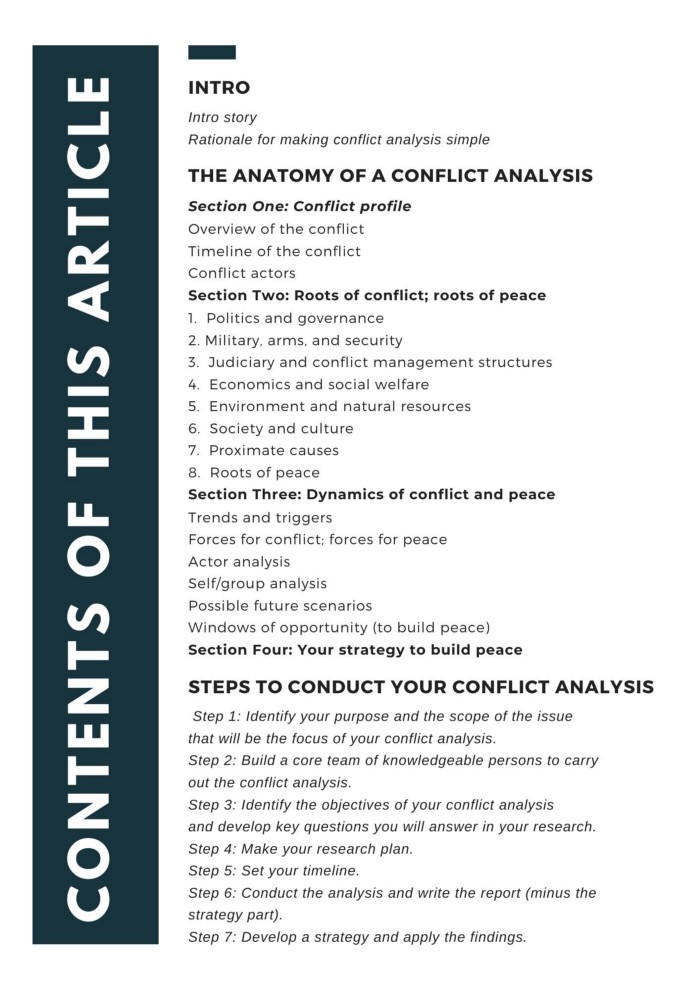

There are lots of sections in this article and you may have to jump around a bit if you’re actually using it to conduct a conflict analysis. So to you help navigate the guide, I put together a little table of contents for you. See below.

The anatomy of a conflict analysis

The anatomy of a conflict analysis

So here, I’ve produced a basic structure of how I would organize a conflict analysis. It has similarities to report structures recommended in guides from some big NGOs and UN agencies, but you’ll find it is also quite different. I organized everything in a logical manner, so each section builds on the previous. Also, I’ve taken out the technical stuff. It is a basic structure that you are free to use as-is or adapt to fit your needs.

Let’s go for 7–10 pages, or 5–7 pages if you want to do a quick one. More than that gets too technical, and the important stuff gets buried.

Here’s the basic structure we’re looking at, broken down into four sections, page number estimations included:

1. Conflict profile (2–3 pages)

2. Roots of conflict; roots of peace (2–3 pages)

3. Dynamics of conflict and peace (2–3 pages)

4. Your strategy to build peace (one page)

To make this all user-friendly, I’ve broken each section down into sub-sections and included questions and prompts to help you generate ideas for filling out each section.

Let’s get started.

Section One: Conflict profile

You want to start by establishing your understanding of the conflict and the context it has emerged within. Think of this section as an introduction to the conflict, which you will use to inform the analysis in later sections. You want to provide a general overview of the conflict while noting any key episodes of violence and other effects of the conflict.

Don’t get drawn into analyzing the conflict dynamics. That will come later.

I’ve broken this into three sections: 1) overview of the conflict, 2) the conflict timeline, and 3) conflict actors. You can write approximately a page or less on each.

Overview of the conflict

Here you’ll describe what the conflict is generally about, note the main people or groups in conflict, and briefly explain why the conflict started and when. And while you’ll be noting major political, economic, socio-cultural issues associated with the conflict and other stuff like that, keep it surface level. The more in-depth analysis comes later.

First, describe what kind of conflict this is. Possible examples include:

- War or armed conflict, including displaced persons and/or refugee movements

- Violence committed by gangs, private militias, mafia groups, or others

- State violence, police brutality, arbitrary arrest, or illegal detention

- Politically motivated violence or hate crimes, including scapegoating and mobilization of people to respond to internal or external threats, real or perceived

- Ethnic/religious violence or hatred, or religious persecution

- Competition over land, water, or resources

- Riots and uprisings, including peaceful demonstrations that indicate there is conflict about something

Now, describe what the consequences of the conflict are. If there have been specific acts of violence committed, describe these. If there was a series of critical events in the trajectory of the conflict, describe these.

Consider:

- Which people or groups have committed acts of violence or aggression?

- Who are the people harmed by the conflict, and how are they harmed?

- What other key people and groups are involved in this conflict?

Lastly, briefly describe key emerging issues that people are fighting over. These may include major political, economic, or social issues or grievances voiced by key individuals or groups, but this should not include in-depth analysis. This comes later. So just include the main issues that people are fighting over. If external influences have a strong influence on conflict dynamics, note this here, but if it isn’t a significant factor, it isn’t necessary here.

Timeline of the conflict

It is essential to know critical events in the trajectory of the conflict.

Key questions to consider here:

- When did the conflict start? How did it develop over the last years or months?

- Is there a history of violence/conflict? Are there any significant events in the history of the conflict?

- Has there been any displacement or major population movements? When did these happen?

- Have there been any major phases that the conflict has passed through? How have conflict dynamics changed over time?

- Across the timeline of the conflict, have there been significant periods of conflict escalation or de-escalation? Periods of heightened tension?

- Have there been any efforts to mediate between key individuals/groups or to resolve critical issues?

It is optional to include a visual of the conflict timeline. This may be a shorter-term timeline of key events, or it may be a timeline mapping key events in a longer history of the conflict. Some conflicts date back many years, decades, or even centuries. Sometimes there has been a recent resurgence of violence amidst a long history of conflict. If this is the case, you may want to include two separate timelines: one mapping recent episodes of violence and the other mapping the history.

Timelines can be presented in a number of ways. There is a description of one method of producing a timeline in my article: 3 Simple Conflict Analysis Tools That Anyone Can Use

Conflict actors

In this section, you will provide a brief overview of all the key persons and groups involved in the conflict. This can be any influence, both positive or negative, for or against peace.

Begin by brainstorming a list of any persons and groups involved in driving the conflict, those affected by conflict, and those working for peace.

Possible actors include:

- The national government, as well as political parties, groups, and networks

- Military, police, or security sector actors; or armed groups

- Businesses, multinational corporations, or other private sector actors

- Religious, cultural, or traditional leaders/authorities; religious/cultural groups and networks

- Grassroots organizations, local activists groups, peace groups, youth or women’s organizations, or other civil society organizations

- Neighboring states, regional organizations (e.g., African Union); also UN agencies, international NGOs, donor agencies, foreign embassies, etc.

- Diaspora groups, refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs)

- Trade unions, teachers groups, medical worker groups, or other organized worker groups

- Influential media entities or groups

Now you will write a brief description of each actor. Keep it brief. This is just an introduction. You will analyze their influence on conflict dynamics later. One short paragraph (approx. 3–5 sentences) on each is fine. This can be shorter for those with lesser influence on conflict dynamics.

Depending on the complexity of the conflict and the number of actors, you may choose to organize them in any manner you choose. Be sure to write in a way that you are explaining it to someone who doesn’t know about the context so that it is accessible to anyone.

The short descriptions of each actor should answer the following questions:

- Who are they?

- What is their role? How do they influence conflict dynamics? Is their influence negative or positive (i.e., towards peace)?

- What interests are they pursuing? Do they have an agenda (or a stated position) that promotes conflict or peace?

Don’t forget to include yourself, your group, or your organization! Put in a short profile of your group just as you have for the other organizations.

Section Two: Roots of conflict; roots of peace

I like to get straight into this section because it is a key part of making a peacebuilding strategy. Recall that your peacebuilding strategy will seek to transform one or more roots of conflict (and/or strengthen roots of peace). So having these clearly outlined here will help you immensely with your strategy.

When you think about the causes of conflict, consider what factors create the conditions for the conflict in the first place. And so, if these causes are removed or transformed in some way, there would either be no conflict or the conflict dynamics would be drastically different.

Causes of conflict can be broken down into different categories. Sometimes they are mapped as structural causes and socio-cultural causes. Sometimes they are considered as immediate causes and ‘proximate’ causes. Sometimes they are mapped as political, economic, social causes. It doesn’t matter how you break it down. What matters is that you consider different types of causes, whatever categories they may fall into.

I’m gonna do a hybrid of these forms and map causes in seven categories:

1 . Politics and governance

2. Military, arms, and security

3. Judiciary and conflict management structures

4. Economics and social welfare

5. Environment and natural resources

6. Society and culture

7. Proximate causes

And you’ll find the section on the roots of peace is at the end.

I’ve inserted a list of questions under each category to help you generate ideas about the causes of conflict. You may generate many ideas, but you should try to narrow down just the most critical causes of conflict. Identifying five to seven clear causes is a good number. And you may have up to ten. If you come up with more than ten, try to combine some that are similar.

1. Politics and governance

Politics and poor governance are common causes of conflict.

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with politics and governance, consider the following:

- Do some groups perceive the government as illegitimate?

- Are diverse groups equitably represented in political parties and government institutions? Are diverse interests represented?

- Are there proper checks and balances in the political system? Is there endemic abuse of power?

- Do some groups cite systemic racism or discrimination in key government institutions?

- Is there real or perceived corruption at any level? Is this corruption widespread?

- Do political leaders exploit ethnic/religious/cultural differences? Do they mobilize people around ethnic nationalist or exclusionary ideologies?

- Do corporations have undue influence on political processes?

2. Military, arms, and security

Militarization, arms proliferation, and poorly regulated or discriminatory security structures are common, often overlooked causes of conflict. Thus, I have made this a separate category. If there are high levels of armament and militarization in any context, this will lead to a high likelihood of violence, both perpetrated by the state (i.e., military, police, and security forces) and also against the state (i.e., insurgency, rebel groups, etc.).

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with military, arms, and security, consider the following:

- Does the country have a high level of military spending? What portion of the national budget is spent on defense?

- Do police have access to and use military weaponry, vehicles, and gear?

- Are military and security structures discriminatory? Are diverse groups represented in the military and police?

- Do military and police operate in a discriminatory manner? Is police brutality or state violence a problem?

- Is there a thriving war economy or arms trade? Are certain groups profiting from war, violence, or the threat/fear of violence? Is there an influential gun/weapons lobby? Does the population have easy access to weapons?

- Do all ethnic and religious groups feel safe and protected by police and security forces? Do they express feelings of unequal treatment by security personnel?

3. Judiciary and conflict management structures

Conflict management structures are essential to resolve conflicts when they emerge. Weak or non-existent structures increase the likelihood that conflicts escalate to violence. Conflict management structures may be formal (like a judiciary system), and they may be informal (like community leaders or councils). Institutions of criminal justice, incarceration, and lawmaking may also be analyzed here, as well as informal structures where relevant.

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with the judiciary and conflict management structures, consider the following:

- Is the judicial system representative of the population?

- Do all ethnic, religious, cultural, social classes, and other groups feel that the justice system treats them fairly and equally? Do people have fair and equal access to justice?

- Is the capacity of the criminal justice system weak or discriminatory in any way?

- Are religious, cultural, and civil rights protected? Is there freedom of speech and freedom of the press?

- Are perpetrators of state violence prosecuted?

- Do local mechanisms exist to solve community conflict? How well does it function? Is everyone pleased with how it functions? Is it representative of the population?

4. Economics and social welfare

I put economics and social welfare together because they are linked. Consider the degree of economic equality experienced by diverse populations in any given context. Sound economic management will produce a robust economy which should, in theory, benefit all people. The nature of a country’s education, healthcare, and social welfare systems are key factors that determine the level of access diverse populations have to resources and opportunities.

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with economics, consider the following:

- Do economic policies create a stable economy that creates equitable access to opportunities across a broad cross-section of the population?

- How prevalent is social and regional economic inequality? Do all diverse populations feel that they have the same degree of access to economic opportunities?

- Is wealth concentrated in the hands of a few? How wide are the margins of wealth and income inequality? Are they increasing or decreasing? Is there a large economic gap between rich and working-class people?

- Do the rich (and especially the super-rich) pay their fair share of taxes? Does the government adequately distribute wealth through its tax system?

- Are there widening economic disparities across regions, ethnic groups, or other factors? Is the economic system discriminatory?

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with social welfare, consider the following:

- Do people have equitable access to quality education? Do some groups consistently have access to higher quality education? Does free education exist, and if so, to which grade?

- Do people have equitable access to healthcare? Do people have access to affordable medicines?

- Do people have access to affordable housing? Do the poor have access to adequate housing? Is there a housing system for the poor? Do ghettos and slums exist?

- Is there equitable distribution of roads, sanitation, electricity, internet, and other public infrastructure? Do people have access to these things in a fair and equitable manner?

- How are social inequalities and regional disparities addressed?

5. Environment and natural resources

Destruction of the environment and unfair access to natural resources can also cause conflict. Environmental destruction, including pollution, can harm people’s health and livelihoods.

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with the environment and natural resources, consider the following:

- Is there endemic destruction of the environment and natural resources? How are people affected?

- Do some populations disproportionately suffer the adverse effects of pollution or environmental destruction more than others?

- Are structures in place to protect the environment? Are there laws to preserve and protect the natural environment? Are they enforced?

- How sustainable is the state’s environmental policy?

- Are there resource extraction projects that destroy the environment?

- Does one group or party control the majority of resources? Is there competition over land, water, or other natural resources? Is there real or perceived natural resource scarcity? Do all people have access to clean water?

6. Society and culture

Most conflicts have some socio-cultural causes. When analyzing this section, you must have a clear and sensitive understanding of socio-cultural issues. In conflict, it is common that some groups cast blame on others. Your analysis here must be insightful, balanced, and fact-based. Consider the ethnic, religious, and cultural background of those conducting this conflict analysis and those providing input. Be sure the voice of marginalized groups is heard and expressed here.

To analyze the causes of conflict associated with society and culture, consider the following:

- Is there a legacy of past conflict, injustice, and/or inequality?

- Can the national identity be described as inclusive or exclusive? Do all diverse people agree?

- Are there cultural biases against some minority groups? Do some minority groups commonly describe structural discrimination?

- Are some cultural groups feel excluded from cultural celebrations or social life?

- Are there any pronounced ethnic or religious divisions? Are there any tensions over language, religion, or ethnicity? How strong are feelings of (ethnic) nationalism?

- Do some cultural groups share vastly different perspectives on the conflict?

Also, consider specific elements of culture:

- Do education systems glorify war and/or obscure the legacy of historic injustice?

- Do movies, TV, and influential news media entities stoke patriotism or nationalism? Do they promote or celebrate war? Do they spread racist or discriminatory narratives? Do they rationalize systemic racism and inequality?

- Are the perspectives and contributions of some (marginalized) groups excluded in public education, media, art, and/or events/holidays?

- Do monuments celebrate war ‘heroes’ or symbols of hate and injustice?

7. Proximate causes

In this section, you should consider if there are any international or regional dimensions of the conflict. Sometimes analysis is limited to the local and national context but excludes powerful external (i.e., proximate) forces that were a critical factor in producing the conflict.

To analyze proximate causes of conflict, consider the following:

- Is the country affected by external threats that are beyond their control?

- Are other countries interfering in the elections or politics of the country?

- Is there conflict, political changes, or other forces in neighboring countries affecting conflict dynamics in this country?

- Are large multi-national corporations causing any problems to the economy, destroying the environment, or interfering in political processes? Do they have a high degree of influence on political decision-makers?

- Are there specific effects of climate change that pose specific challenges or act as a destabilizing force?

- Do diaspora populations influence conflict dynamics? (positive or negative)

- Is there international or regional cooperation to address shared challenges? Are UN agencies, NGOs, donors, and other international aid actors contributing to conflict dynamics in some way?

Roots of peace

Conflict analyses seldom include proper analysis of the roots of peace, but just as we can identify roots/causes of conflict, we too can identify roots of peace.

To uncover roots of peace, consider the following:

- What is the history of peace? Are there specific historical events and/or historical persons that represent peace?

- Are there systems and institutions that historically have promoted peace or resolved conflict?

- Are there shared festivals, holidays, rituals, or traditions?

- What cultural attitudes and values promote peace?

- Do people have any shared experiences of joy or suffering across division?

- Are there any shared cultural symbols that represent peace?

- Are there any longstanding traditions of resolving conflict peacefully?

Section Three: Dynamics of conflict and peace

Mapping conflict dynamics clearly will help identify opportunities to build peace amidst current dynamics. Here is where you describe how conflict actors interact with the roots of conflict and peace. This section includes an analysis of conflict trends and triggers (of violence), forces for peace and forces for conflict, dynamics of actors involved in the conflict, and of you or your group’s interaction with the conflict, as well as a mapping of possible future scenarios and identification of windows of opportunity (to build peace).

Trends and triggers

In this brief section, you may analyze long-term patterns in conflict dynamics. It is good to associate this with the timeline included in the conflict profile. You will identify triggers of violence and any patterns you notice that have emerged in conflict dynamics.

Triggers are events or flashpoints that spark an outbreak of violence. You will often hear about triggers when the media describes the conflict. They are most apparent when violence happens. They are not the cause of conflict. Triggers are surface level.

Triggers can often be anticipated. Examples of triggers may include:

- Heated elections or a flawed election process

- Rallies by hate groups or events by divisive leaders

- A particular holiday with nationalist themes

- Arrest or assassination of a political figure or leader

- Expansion of military bases or troop movements

- The opening or confirmation of a planned economic project; landgrabs

- A natural disaster, possibly seasonal or recurring natural disasters

- A sudden change in the price of fuel or goods, or a collapse of currency

- Incidents of police violence; crackdowns on protesters

Sometimes conflict actors will intentionally create triggers to ignite violence. I did a conflict analysis once where I noted that events held by an influential leader of a hate group in any particular area indicated the likelihood of mob violence weeks later.

To identify trends and triggers, answer the following questions:

- Is violence or tension increasing or decreasing?

- What is determining the future path of the variable, and how is it likely to develop?

- What triggers can be observed? What happened weeks before episodes of violence?

- What triggers might spark violence or an escalation of the conflict? Are any triggers foreseen in the coming year or so?

Forces for conflict; forces for peace

Most conflict analyses include forces for conflict, often called drivers of conflict or dividers. Some also include forces for peace, sometimes called connectors, bright spots, or other. I think it is essential to include both, and since they are associated with each other, I describe them as forces for conflict and forces for peace.

Forces for conflict in themselves are distinct from both causes of conflict and triggers. They are current, ongoing forces that are driving conflict. They are associated with one or more causes of conflict, and they may themselves create triggers or respond to them with an escalation of violence or tension. They act to escalate or prolong conflict.

Some examples of forces for conflict (aligned with the seven sections on conflict causes) may include:

- Efforts to produce or implement exclusionary or discriminatory laws or policies; laws or policies that legalize corruption or enhance the influence of corporations and the super-rich on political decision-making; efforts to exclude some groups from political decision-making

- Increased militarization; the establishment of paramilitaries or militias; increases in military/defense spending, expansion of or development of a war economy, or increased availability or sale of weapons

- Current discrimination in judicial system processes and mechanisms, or in local conflict resolution mechanisms; inequitable representation of diverse groups amongst decision-makers in the criminal justice system, or in local conflict resolution mechanisms

- Production of laws that produce economic inequality or widen the gap between the rich and the poor; laws/policies that promote discriminatory access to education, healthcare, or social services

- Expansion of harmful economic projects or activities that are destructive to the environment

- Nationalist/exclusionary rhetoric from politicians, hate groups, or others; efforts to exclude people from holidays, cultural events, or celebrations; civil society groups agitating conflict

- Political changes or changes in conflict dynamics of neighboring countries that have a negative influence on conflict dynamics; new policy decisions of influential countries, UN agencies, or international actors that negatively influence conflict dynamics

Forces for peace can build the foundation for your peacebuilding efforts. They are different from the roots of peace in that they are current, ongoing forces that are building peace. They are often associated with transforming one or more causes of conflict, but in some cases, they focus on the positive construction of peace. They are not directly associated with transforming a cause of conflict. They act to build sustainable peace.

Some examples of forces for peace (aligned with the seven sections on conflict causes) may include:

- Efforts to produce or enforce anti-discrimination laws; government reform efforts, laws or policies that uproot corruption and promote transparency; efforts to promote equitable representation of diverse groups in political decision-making

- Demobilization of armed groups or demilitarization of the military/police; decreases in military spending; gun control, controls on the arms trade, decreased availability of weapons

- Reform of judicial systems or local conflict resolution mechanisms; establishment of new mechanisms for conflict management; the opening of communication channels between groups in conflict

- Production of laws that produce economic equality or narrow the gap between the rich and the poor; efforts to produce or enforce laws/policies that promote equitable access to education, healthcare, or social services

- Efforts to restrain harmful economic projects or activities that are destructive to the environment; efforts to promote sharing of natural resources

- Civil society peace initiatives or cooperative projects with those in conflict; inclusionary rhetoric from politicians, religious groups, or others; events/holidays that bring people together across divides; collaboration across ethnic, religious, or cultural divides

- Political changes or changes in conflict dynamics of neighboring countries that have a positive influence on conflict dynamics; new policy decisions of influential countries, UN agencies, or international actors that positively influence conflict dynamics

To identify forces for conflict and forces for peace, consider the following questions:

- What new factors contribute to violence or prolong conflict dynamics?

- What factors can contribute to peace?

- What groups are driving conflict? What are they doing?

- Are there existing peace initiatives? At what level? Are they working to address the causes of conflict? What have they achieved?

- How are key local, national, or international media actors covering the conflict? Are they promoting peace and the resolution of critical issues, or are they agitating the conflict?

Actor analysis

In this section, you will briefly analyze the dynamics that occur amongst conflict actors. You will analyze their influence on conflict dynamics and interactions with each other. This isn’t a detailed description of the causes of conflict. This is to understand the role of key actors and how they interact (or don’t interact with each other).

Briefly answer the following questions:

- Which actors are working to drive conflict? Which actors are spoilers (i.e., those who are or may seek to disrupt peace processes or efforts for peace, who benefit from ongoing conflict in some way)? What is their degree of influence on conflict dynamics?

- Which actors are working for peace? And which actors have interests that give them the potential to work for peace? What is their degree of influence on conflict dynamics?

- Do conflict resolution mechanisms exist? How strong and functional are they?

- What relationships or networks are key to conflict dynamics? Are there key alliances between actors? Do some strong relationships or weak relationships have a crucial role in conflict dynamics? What tensions are present, and how are they relevant to conflict dynamics?

Note: Examples of conflict resolution mechanisms include the formal judiciary, political institutions (i.e., head of state, parliament), informal systems or approaches (i.e., traditional authorities, community processes, etc.), regional mechanisms (i.e., African Union, ASEAN, etc.), or multilateral bodies (i.e., International Court of Justice, etc.).

If there is a particular conflict between two distinct actors, it may be helpful to use the PIN Model to analyze the positions, interests, and needs of conflict parties. If the main conflict involves more than two distinct actors, I don’t recommend using this model. There is a description of how to make a PIN Model in my article: 3 Simple Conflict Analysis Tools That Anyone Can Use

Self/group analysis

In this section, you will analyze your own influence on conflict dynamics. Make sure you include an analysis of your group and how your group interacts with conflict dynamics. This can provide you with ideas for engaging with conflict actors, building collaborative partnerships, and ultimately taking strategic actions for peace.

Consider the following questions:

- How do key conflict actors perceive your group?

- Has your group had any influence on conflict dynamics in the past, either positive or negative?

- Does your group have any relationships with key actors? How may these benefit your actions for peace?

- Are there any key actors that have a negative perception of you or your group? How does this affect conflict dynamics?

- Do any of your group’s activities create tension amongst key actors or negatively influence conflict dynamics? Have there been any issues or challenges in the past?

Possible future scenarios

In this section, you should review your analysis of the conflict dynamics to determine possible future scenarios. You will need to make a judgment on which scenarios are most likely and why. And you will use this to develop your strategy to build peace. You should review a range of possible scenarios and determine which are the most likely.

Ask yourself:

- What is the likelihood that the conflict dynamics might improve to move towards peace? Why? And what might that look like?

- What is the likelihood that the conflict dynamics might worsen? Why? And what might that look like?

This section may be brief or expanded depending on the conflict’s complexity and the likelihood of possible future scenarios. You will want to select possible scenarios, describe them, and explain what factors would contribute to these outcomes. It is helpful to determine a specific timeframe. This may be arbitrary or may be determined by patterns in conflict dynamics or upcoming events.

Sometimes specific scenarios are apparent. There may be two clear scenarios, or there may be many. The task is to determine the most likely scenarios, including both positive and negative outcomes. If the number of scenarios is too many or it is difficult to determine amongst a range of scenarios, it is helpful to identify three scenarios: 1) the best-case scenario, 2) the word case scenario, and 3) a potential scenario where conflict dynamics remain relatively constant.

It may be helpful to conduct a brainstorming session with key team members to analyze possible scenarios. Contrasting perspectives and friendly debate can be helpful for this section.

Windows of opportunity (to build peace)

Here, analyze your possible scenarios and briefly identify some windows of opportunity where some action can be taken (by anyone in general) to contribute to moving conflict dynamics in a positive direction. Possibly there are upcoming events that might create opportunities.

Ask yourself:

- What factors support moving the conflict dynamics in a positive direction (possibly towards a specific favorable scenario previously identified)?

- What can be done (in general, by anyone) to strengthen the influence of these factors?

- Are these opportunities time-bound? What is the timeframe that any particular ‘window of opportunity’ is available?

Section Four: Your strategy to build peace

With conflict dynamics mapped, you’ll have a good idea of some entry points, project ideas, or actions you can take to build peace. You may have many ideas, and if so, it will be good to narrow it down to one or more of the most practical and effective approaches.

But first… when making a strategy to build peace, there is one VERY IMPORTANT thing you should remember: Strategies to build peace must address one or more of the roots of conflict (and/or strengthen one or more roots of peace).

You can have some activities to address the effects of conflict if you want, to help people affected by violence, or to support those suffering in some way, and this is great, but it will not build peace in the long run. Transforming the causes of conflict will!

So take a look at the ideas you have and ask yourself if they are clearly addressing one or more of the causes of conflict you’ve identified (and/or strengthening one or more roots of peace). If they are not, take these ideas out. They may be part of some activities you are involved in, but they are not part of a strategy to build long-term, sustainable peace.

So, to get started on your strategy for building peace, ask yourself:

- What can we do to address one or more of the roots of conflict? What can we do to strengthen one or more roots of peace?

- What can we do to mitigate the effects of forces for conflict? What can we do to mitigate any potential triggers? What can we do to support forces for peace?

- Are there any windows of opportunity that we should take action on?

- What plan of action will we take? What outcomes do we hope to achieve?

Once you have an idea of what course of action (or actions) you may take to build peace, to put your plan into action, consider the following:

- Do we have the necessary skills, knowledge, and resources to take the needed actions? How can we build them?

- What relationships can be developed or leveraged that will maximize our chances for success? Are there any relationships that we have with conflict actors that will help us? Should build any new relationships? Should we strengthen some existing relationships? Would it be useful to build a coalition?

- Do we have sufficient political support (local or national)?

- Is there a possibility that the action we plan to take, directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally, might cause harm or contribute negatively to conflict dynamics?

- How will we know that we have made a positive contribution to build peace? How will we know that it is working? That our actions are effective? That they are producing positive outcomes?

Steps to conduct your conflict analysis

Now that you have a good sense of the structure of a conflict analysis report, you’re ready to conduct your conflict analysis. Key steps in conducting a conflict analysis are provided below, together with questions to help you in the process.

Step 1: Identify your purpose and the scope of the issue that will be the focus of your conflict analysis

Before you start a conflict analysis, you must be clear about what you are conducting it about, why you are doing it, and what you hope to achieve.

Questions to consider:

- Why are you conducting this conflict analysis? What is the particular conflict/issue you will be conducting this conflict analysis on? Is it a conflict in a specific geographic region (local, national, international)? Is it a conflict or issue with a specific theme?

- How will this conflict analysis be used? Will your organization or group use this to develop a strategy? Will you use this to develop advocacy messages? Will it be part of a coalition effort to develop multiple strategies to take on an issue?

- Who will be reading the final report?

Write a (2–3 page) draft of the Conflict Profile section of the report.

Step 2: Build a core team of knowledgeable persons to carry out the conflict analysis.

If your conflict analysis is small-scale, your team may just be you, and if so, I recommend inviting a knowledgeable friend or two to support you. If you are a small group or organization, you may appoint a few key individuals, and you may be involved yourself. And if acting in a coalition, try to get representation across member groups.

Questions to consider:

- How many people are involved in the core team? Who will lead the conflict analysis and write the report? Will partner organizations be involved?

- Who should provide inputs in the process and review of the report drafts? How will you ensure that multiple perspectives are considered?

Share your draft Conflict Profile with the core team for review.

You may ask key team members to review my article on A Typology of Violence to help sharpen their ability to analyze conflict and violence.

Step 3: Identify the objectives of your conflict analysis and develop key questions you will answer in your research.

In this step, work with your core team to do the following things, in this order:

- Analyze the conflict profile, discuss differences of opinion, and finalize the draft so everyone agrees about the conflict profile.

- Review the section of this article on ‘roots of conflict; roots of peace.’ See if your team can map the roots of conflict and roots of peace. Identify gaps in knowledge and differences of opinion.

- Review the section of this article on ‘dynamics of conflict and peace.’ Identify gaps in knowledge and key differences of opinion.

- Use gaps in knowledge and differences of opinion to map topics that your conflict analysis can research.

- List 2–3 key objectives of the conflict analysis that outline what you hope to learn from conflict analysis research. List 5–7 key questions that you hope to answer in the research.

Consider first conducting some warm-up exercises with your core team. I recommend making a Conflict Tree with those most directly involved in conducting the conflict analysis. See my conflict tree activity in my article 3 Simple Conflict Analysis Tools That Anyone Can Use. The ‘roots of conflict’ that you identified in this activity should align with the roots of conflict of this report, and the ‘core problem’ and ‘effects’ mapped in the activity will help you discuss and map conflict dynamics.

Step 4: Make your research plan.

To make a research plan, you need to do three things: 1) determine your data collection methods, 2) decide your sources of information, and 3) develop tools.

The three most common methods used for collecting data are a review of literature, interviews, and focus group discussions. Review of literature can be as simple as reviewing articles about the conflict online and/or in local media. Interviews can be conducted with key persons with specific information and/or with representatives of groups affected by the conflict. And focus group discussions sound formal, but basically, they are just having a discussion with a small group of people and documenting their feedback.

Other methods may include observation, questionnaires/surveys (a bit more technical), or participatory methods. Participatory methods may involve organized activities, games, art, or theater activities. If you don’t have experience with this kind of stuff, I recommend sticking with interviews and focus group discussions and reviewing literature if necessary.

Questions to consider:

- What information needs to be gathered to answer your key questions?

- Where can we find this information? Who can we talk to? What perspectives do you want to include in the analysis?

- Who are key persons or groups involved in the conflict? Who is affected by the conflict? Who has in-depth knowledge of conflict dynamics?

- How will you collect information from the people and groups you identified? What methods will you use? What tools need to be developed?

You should make a list of information you need to gather for each of your key questions and where you can find this information (i.e., who will you talk to). Then determine which method (or methods) you will use and develop data collection tools as necessary. If conducting interviews and focus groups, this means you will develop a list of questions to ask people. Sometimes you will ask everyone the same questions to see differences of opinion. Other times, you may ask different people different questions if different people have different information you need to gather.

Step 5: Set your timeline.

Now you’re ready to put your plan into action.

Questions to consider:

- How long will the planning process take? What is the timeframe for data collection? How much time should be allocated for writing and editing? How many drafts will be produced, and who will provide input on each draft in the editing process? When will the final report be complete?

- What will be done with the report once it is complete? Will you be using it to develop a strategy? Will you be developing advocacy messages from it? Will it be part of a coalition effort? Will there be events or workshops where the report is used?

Step 6: Conduct the analysis and write the report (minus the strategy part).

Now carry out your plan. Conduct your research. This may take a few days or a few weeks. When you’re done, you’ll need some time to analyze the data. Then write the report, specifically the sections on ‘Roots of conflict; roots of peace (2–3 pages),’ and ‘Conflict Dynamics (2–3 pages).’ You may have a process for input from key persons and editing.

Who is involved in the editing process is up to you. My advice is to select people who have in-depth knowledge about the conflict dynamics. These may be people you are working with, they may be partners, and they may be external people whose input you respect and trust. Try to pick reliable people. Lack of input or late input can disrupt the process.

Finalize the report, so it is ready for a brainstorming session on developing a strategy.

Step 7: Develop a strategy and apply the findings.

If the conflict analysis was done well, it may have given you many ideas for strategies and specific actions you can take to build peace.

Before you begin, recall that when making a strategy to build peace, there is one VERY IMPORTANT thing you should remember: Strategies to build peace must address one or more of the roots of conflict (and/or strengthen one or more roots of peace).

You can approach this step in one of two ways:

- You may use the detailed strategic planning process outlined in my article The 10 Steps of Strategic Peacebuilding

- You may use the prompts in the “Your Strategy to Build Peace” section in this report for a quicker strategy development process.

Additionally, you can find some creative ideas for actions you can take in my article, 198 Actions for Peace.

I hope you found this tool useful and practical. And I hope you use it to clarify your purpose, build actionable strategies for peace, and ultimately build peace better and more effectively.

Find ways you can build peace in the world around you. Download my free handout 198 Actions for Peace.

_____________________________________________

Taylor O’Connor, MA Peace Education, UN Mandated University for Peace, 2009. Taylor is a rebellious peacebuilder, peace educator, and founder of the blog Everyday Peacebuilding. Freelance Peacebuilding Technical Specialist by day, he’s working to make insights from peacebuilding practice relevant and practical to wider audiences. If you’d like to learn some creative and strategic ways you can build peace in your life and in the world around you, get his free handout 198 Actions for Peace – also good for educational settings.

Taylor O’Connor, MA Peace Education, UN Mandated University for Peace, 2009. Taylor is a rebellious peacebuilder, peace educator, and founder of the blog Everyday Peacebuilding. Freelance Peacebuilding Technical Specialist by day, he’s working to make insights from peacebuilding practice relevant and practical to wider audiences. If you’d like to learn some creative and strategic ways you can build peace in your life and in the world around you, get his free handout 198 Actions for Peace – also good for educational settings.

Tags: Conflict, Conflict Analysis, Conflict Mediation, Conflict Resolution, Conflict Transformation, Social conflict, Trauma, Violent conflict

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION: