Listening to the Silence with Don DeLillo

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 7 Dec 2020

Edward Curtin – TRANSCEND Media Service

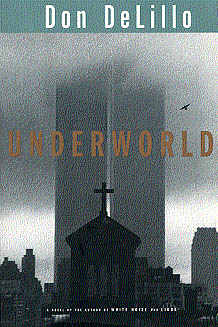

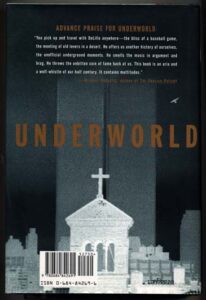

5 Dec 2020 – In 1997, Don DeLillo, the author of seventeen novels, published what many consider his masterpiece, Underworld. It was a prophetic book in many ways, especially with its focus on the World Trade Towers and the way the book’s cover, front and back, pictured the towers shrouded in smoke or clouds with what seemed like a large bird approaching it at its upper floors. That the front cover had a positive image and the rear a negative one with the light and dark inverted gave it a ghostly look that was haunting. I remember when I first saw the book, I wondered if the photograph was showing a plane or a bird approaching the north tower near what looked like twenty or so floors from the top. I concluded it was probably a bird, but four years later reality entered the picture with a plane exploding into the side of the building twenty or so floors from the top.

The photo is ambiguous but eerily suggestive, especially in retrospect. Below the towers we see a cross atop the local church seemingly holding the towers together, as if to announce the future of the new Crusade against Islam, or perhaps the connection between God and Mammon, or maybe a reminder that “you cannot serve God and mammon.” Who knows?

No one seeing it now could avoid thinking of the attacks of September 11, 2001. And reading the words of the character Brian, who is in the waste management business, one realizes why the cover photos were an appropriate choice and how they captured DeLillo’s story and the terrible future. Fresh kills and burials. The underworld. Brian thinks as he stands atop the mountains of waste at the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island and looks at the Twin Towers across the harbor: “The towers of the World Trade Center were visible in the distance and he sensed a poetic balance between that idea and this one.” Does Brian know that soon nearly three thousand people will be wasted there? And that his twinning of the towers with waste would soon take on the creepiest of meanings. “The wind carried the stink across the kill.”

Ezra Pound once said that artists are the antennae of the race. He seemed to be speaking of DeLillo, among others. Can artists intuit the future? Did DeLillo realize the fate of the Twin Towers? How?

When I read Underworld, I was struck by its uncanny brilliance. This was in 1998. I recommended it to everyone I knew. No one would read it. It was too long – 827 pages – and maybe something closer to the bone dissuaded them, as if its title was announcing dread and death and they preferred smiley faces. Then, after the attacks of September 11, 2001, I again recommended it. No one took my suggestion to read it. Perhaps then it wasn’t the length but its eerie insights. Its prescience. Its weirdness. Its references to the Twin Towers, terrorists, the view of the Towers from the Fresh Kills landfill where the debris from the attack was in fact later taken and laid to waste as fast as possible to avoid inspection, buried, the reference to germs and the fear of them, the need to wash your hands over and over, the traumatic looping of images on television, so much repetition, such frantic sex, loss of faith, nuclear dread, etc. The book was capacious and captivating and unnerving.

“What’s your argument?” one character asks another.

“You asked, so I’ll tell you. That the biggest secrets are staring us straight in the face and we don’t see a thing.”

Or don’t want to.

What are those open secrets now?

DeLillo’s latest book is The Silence, which is called a novel but is really a long short story or a novella. But the categories don’t matter. It’s a meditation in words on silence, death, technology, and loss, always the heart of the matter and DeLillo’s core themes. It is very short – 117 pages of big print. All the characters talk gibberish, inanities that cut to the bone. It’s hard to know whether to laugh or cry when hearing them talk. Yet much of their talk is frightening because it is the way people do talk to each other. The sounds of silence. What did you say? What? What did you say? I don’t remember, I was texting.

And like Underworld, whose first 150 pages are devoted to the first nationally televised baseball game played on October 3, 1951 at New York’s Polo Grounds that ended with a ninth inning home run by the Giants’ Bobby Thompson that came to be called “the shot heard round the world,” The Silence centers around a group of five people gathering in 2022 to watch the Superbowl on a superscreen TV in a Manhattan apartment.

Sport: from old French, desporter, to divert; literally, to carry away. From what? To where?

“Filling time. Being boring. Living life,” says Tessa to Jim who are on a plane returning from France. Jim is fixated on the screen in front of him that is flashing the plane’s altitude, the temperature, time to destination. Tessa is writing in a small notebook her memories of what they saw on their trip so that in the years to come she may realize what she had missed, “something I don’t see right now.” Both killing time. Jim jabbers on about nothing, but he “wasn’t listening to what he was saying because he knew it was stale air.”

Back in the NYC apartment a threesome is awaiting their arrival for the big viewing of the Superbowl. Drinks and snacks are ready. There sit Diane, Max, and Diane’s former student, Martin, who is in his early thirties. Routine, boredom, and ennui await the kickoff and the arrival of the other couple and expected excitement. The national diversion on a small scale. A question hovers in the air: “What are we doing here, that is the question,” says Vladimir in Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot. “And we are blessed in this, that we happen to know the answer.”

Do we?

Back on the plane, something happens, “a massive knocking somewhere below them. The screen went blank.” Knock, Knock. Who’s there? Death. “Are we afraid?” she said. The plane crash-lands because all the electronics have failed.

Back in the high-rise aerie, the threesome talk in clipped voices like the robotic Alexa. While her husband Max sits and drinks bourbon and stares at the big screen, Diane, in search of something to excite her, prods the gangling Martin with absurd questions to which he quickly responds with gibberish that gives her a sexual frisson. Boredom is a powerful force.

The kickoff is minutes away. “Something happened then.” The images on the screen shake, get distorted, and then the screen goes blank. Their phones go dead. At first they think it is a local outage, but it soon becomes apparent that what happened on the plane was happening everywhere and that the entire electronic grid was down, all electricity, the internet out. Max keeps staring at the blank screen, cursing. He starts announcing out loud the invisible game:

Play resumes, quarter two, hands, feet, knees, head, chest, crotch, hitting and getting hit. Super Bowl Fifty-Six. Our National Death Wish.

Martin tells Diane he is taking a medication, and a side effect can be that others can hear your thoughts or control your behavior. “Yes, we all do this,” he says. “A little white pill.”

It seems madness has walked in. Blank screens. Disoriented minds.

Soon Tess and Jim, after visiting the darkened hospital with others from the plane crash to have Jim’s head wound attended to, walk to the apartment through darkening empty streets for the absent game. Martin says, “Are we living in a makeshift reality? Have I already said this? A future that isn’t supposed to take form just yet?”

The five sit and eat by candlelight as cold joins the darkness of the encroaching night. “Was each a mystery to the others, however close their involvement, each individual so naturally encased that he or she escapes a final determination, a fixed appraisal by the others in the room?”

No one knows what has happened, who or what is behind the digital takedown. Or who they really are. Martin says, “Nobody want to call it World War III but this is what it is.” His madness pours from his mouth, a ranting filled with the kinds of questions and thoughts many would think if the digital takedown really happened, the kinds of questions more and more people are now asking. Will DeLillo be prescient again: Is a digital “attack” coming soon?

Martin’s words:

Certain countries. Once rabid proponents of nuclear arms, now speaking the language of living weaponry. Germs , genes, spores, powders.

DeLillo:

Cyberattacks, digital intrusions, biological aggressions. Anthrax, smallpox, pathogens. The dead and the disabled. Starvation, plague, and what else. Power grids collapsing. Our personal perception sinking into quantum dominance…And isn’t it strange that certain individuals have seemed to have accepted the shutdown, the burnout?”

The five of them sit and talk on and on in the silence. Each delivers a closing monologue, as if it’s closing time and the last drinks have been served. Say what you want. What has happened? Speak. Was this foreseeable? Have we been zombified? Lost our ability to think, to communicate, to grasp what’s happening around and within us? Have our digital addictions destroyed our humanity? Have we reached our expiration dates? Who is doing this to us?

Your phone is wasted; don’t seek its advice.

Just as he seemed to perceive the attacks of September 11, 2001 four years before they occurred, does DeLillo know something that most would prefer to avoid? Are we like Tessa, who wishes to just go home and return to normality but who feels she is “in a tumbling void”?

When her husband Jim hears her say something about home, “he realizes it is simply fake, a dead language.”

“Home,” he says finally. “Where is that?”

DeLillo has been asking that for decades.

Are we and he like Max, who ends the book understanding nothing and staring into a blank screen?

Or can we see the biggest secret staring us straight in the face?

I can’t help thinking that DeLillo tipped his hand at the end of Underworld when he has the book’s protagonist, Nick Shay, born and bred like his creator in the Italian Arthur Ave. section of the Bronx, say what he longs for:

I long for the days of disorder. I want them back, the days when I was alive on the earth, rippling in the quick of my skin, heedless and real. I was dumb-muscled and angry and real. This is what I long for, the breach of peace, the days of disarray when I walked real streets and did things slap-bang and felt angry and ready all the time, a danger to others and a distant mystery to myself.

Can we get back into our skins or are we doomed to tumble into a void? The signs are not too encouraging.

My wife and I were recently hiking on a narrow mountain trail along which we encountered not a soul. We came to an isolated spot overlooking a valley to the east. We stopped, looked, and listened. Not a sound. Not even birds. Just beautiful silence. There was so much to hear there. When we continued on, we saw a couple with a dog up ahead. The man and woman each wore a mask. When they saw us, mask-less criminals, they quickly stepped off the trail. The woman pulled the dog close to her and the man took out and checked his phone. As we passed, they said not a word, but their eyes spoke fear. I was wondering if the man was texting the police.

__________________________________________

Edward Curtin is a widely published author and a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. His new book is Seeking Truth in a Country of Lies – His website: Behind the Curtain – email: edcurtinjr@gmail.com

Edward Curtin is a widely published author and a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. His new book is Seeking Truth in a Country of Lies – His website: Behind the Curtain – email: edcurtinjr@gmail.com

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 7 Dec 2020.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Listening to the Silence with Don DeLillo, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.