The Destruction of Literary Heritage as a Tool in Ethnic Cleansing (Part 3)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 31 Jan 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

Cultural Genocide: The Intentional Burning of Historically Ancient Books of Bosnia

Over the eons, humanoids have waged brutal campaigns to eradicate designated nations or population groups, without any reservations. Even the Christians, attracted by the lure of entering heaven, embarked on the Fourth Crusade which was really a genocidal conquest of Constantinople in April 1204 when the combined armies of the Fourth Crusade broke into the city of Constantinople and began to loot, pillage, and slaughtered their way across the greatest metropolis in the Christian world. Within months Pope Innocent III, the man who had first called for the Crusade, bitterly lamented the spilling of ‘blood on Christian swords that should have been used on pagans’ and described the expedition as “an example of affliction and the works of Hell.”[1]

In ancient history, events such as the Christian attack of Constantinople, in which the entire city was pillaged until blood of children, women and elderly was literally flowing like water along the alleys and streets of this great Byzantine city, the 20th century saw the emergence of the term genocide and formal recognition thereof with its incorporation into international law. The word “genocide” owes its existence to Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish lawyer who fled the Nazi occupation of Poland and arrived in the United States in 1941. As a boy, Lemkin had been horrified when he learned of the Turkish massacre of hundreds of thousands of Armenians during World War I. Lemkin later set out to come up with a term to describe Nazi crimes against European Jews during World War II, and to enter that term into the world of international law in the hopes of preventing and punishing such horrific crimes against innocent people. In 1944, he coined the term “genocide” by combining genos, the Greek word for race or tribe, with the Latin suffix -cide “to kill”. The term genocide is used to describe violence against members of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group with the intent to destroy the entire group, bringing about its total annihilations without any remaining trace, as if the humanoid entity never did ever exist. The word came into general usage only after World War II, when the full extent of the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime against European Jews and others, including Romanis, Gypsies, Russian prisoners of wars , during that conflict became known. In 1948, the United Nations declared genocide to be an international crime; the term would later be applied to the horrific acts of violence committed during conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and in the African country of Rwanda in the 1990s.

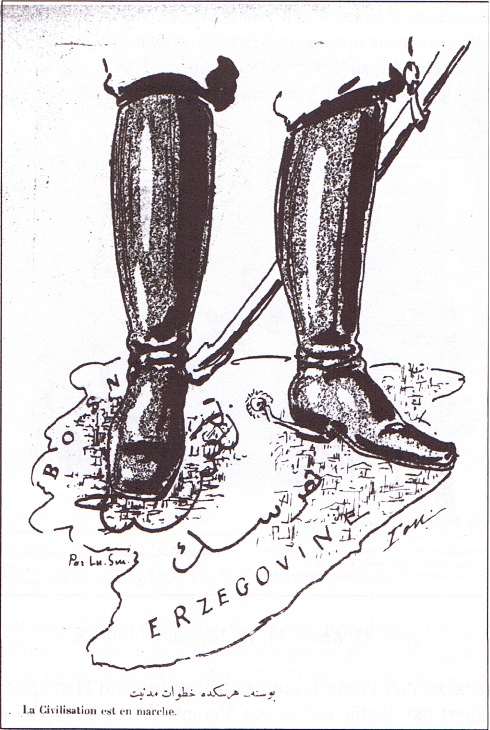

Regarding the Balkans, the Bosnian War began in 1992 and lasted until 1995, though the cause of the Bosnian War has roots in World War II and its impact is still being felt even today. The Bosnian War ( Serbo-Croatian: Rat u Bosni i Hercegovini / Рат у Босни и Херцеговини) was an international armed conflict that took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The war is commonly seen as having started on 6th April 1992, following a number of violent incidents earlier in the year.[2] The Bosnian Crisis was sparked by anger over the annexation of the Balkan regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary. In 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina were officially a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, but Austria-Hungary occupied the territory with the agreement of the rest of Europe (Treaty of Berlin). [3] However, the root cause of the 1992 conflict and genocide lies in the Bosnian Crisis of 1908-09 which added to the complex mix of events that led to the outbreak of World War One. The period is often referred to as the “Balkan Powder Keg”, when this turmoil became entangled with imperialist ambitions and alliances it ignited conflict in Europe.

Geographically, the Balkan region refers to a part of southeastern Europe and includes the countries of Albania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Yugoslavia. In total, the Bosnian Crisis involved nine countries. The Bosnian Crisis in history of 1908, was sparked by anger over the annexation of the Balkan regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary, as an imperialist power at the time. In 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina were officially a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, but Austria-Hungary occupied the territory with the agreement of the rest of Europe following the Treaty of Berlin in 1978[4].

However, on 06th October 1908, Austria-Hungary announced its decision to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Ottoman Empire decried the move and Britain, Russia, Italy, Montenegro, Serbia, Germany and France saw this as a violation of the Treaty of Berlin and became entwined in the crisis. Following Austria-Hungary’s announcement, Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. The Turks, who had ruled Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina for centuries, were unsurprisingly displeased with the annexation and declaration of independence, but were powerless. The Ottoman Empire’s military and domestic power had declined in the past decades. Thus, the Turks could not do much more than demand a financial settlement in exchange for Austria’s annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The annexation caused international tension, particularly in Russia and Serbia. A strong popular opposition to the annexation developed in Russia. Additionally, Serbia was angered by the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which she had hoped to unite into one Serbian nation. The country demanded Austria to give a portion of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Serbia, and the Russian Foreign Minister Izvolsky,[5] pressured by anti-Austrian opinion in Russia, had no choice but to support the Serbian claims. As a reaction, Austria threatened to invade Serbia. In addition, Germany as an Austrian ally, Russia could not risk a war for Serbia’s sake. In March 1909 Alexander Izvolsky notified Germany that Russia accepted Austria’s annexation.

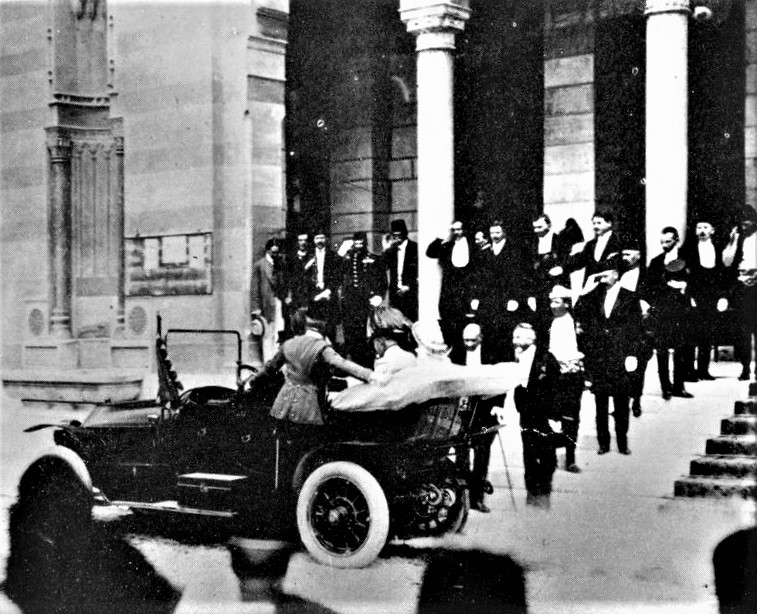

Although a war was avoided, the Bosnian Crisis embittered relations between Serbia and Austria-Hungary. It contributed to the underlying tensions that were ignited when Franz Ferdinand was assassinated at Sarajevo. [6] The assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was the immediate cause of World War One. Europe had become a ‘powder keg’ by 1914 and the assassination was the spark that ignited these tensions. On 28 June 1914, the heir to the Austrian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was visiting the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia’s capital. At this point tensions in Bosnia were high. There was an increasing sense of nationalism, which was embodied in the ‘Black Hand’ movement. These nationalists wanted independence from Austria-Hungary and were willing to use terrorist tactics to achieve this goal. The Archduke was warned that the trip may provoke violence. Serbian nationalists viewed the visit as provocation. The visit was a way of showing off Habsburg rule and it was seen as a provocation by Serbian nationalists. But he decided to go ahead with the visit.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie minutes before their assassination in Sarajevo on 28th June 1914

There had already been problems at the beginning the royal tour when a grenade his another in the entourage. However, Franz Ferdinand wanted to continue, albeit on a route away from the city centre. However, this message was not communicated to the driver who continued through the centre. The driver tried to reverse out onto the main streets after pausing to check where he was. The car stopped five feet from Gavrilo Princip, one of the assassins from the Black Hand. Princip shot the Archduke in the head and his wife in the abdomen. They both died shortly afterwards. A photographer captured one of the most infamous scene from the assassination. If it was not for the pre-existing tensions in Europe, the assassination would never have led to war. Serbia was blamed by Austria for this murder. Serbia was intent on liberating Bosnia from Austro-Hungarian rule and forming a unified Serbian state. Therefore, the country had encouraged the actions of the Black Hand.[7]

Austria planned to invade Serbia as punishment. Serbia called on Russia for help. Russia had a large Serbian minority and many ties with the Balkan region so and she agreed to join Serbia if Austria-Hungary attacked.

Although Serbia would have been easy for Austria to defeat, Russia was much larger and stronger. The Triple Alliance of 1882 meant that Germany had already promised to support Austria in the event of war. Germany became allied with Austria, which in turn provoked the French government. However, decades earlier the German army had created a plan called the Schlieffen Plan. This was a strategy to allow Germany to fight a war on two fronts, in France and Russia. This plan assumed that the Russian army would take six weeks to mobilise itself. During that time, Germans could launch an attack on the French and then fight the Russians.

Germany carried out the Schlieffen Plan when France mobilised the army. They proceeded to attack France via Belgium. At this point Britain entered the war. Britain had promised Belgium protection in 1838, so it had little choice. Due to a combination of alliances, imperialist ambitions and rising tensions, the assassination at Sarajevo triggered the outbreak of war. On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany after the German invasion of Belgium. France and Russia allied with Britain and Austria supported Germany. Every country concerned was convinced that the war would be over by Christmas and not one nation could possibly imagine the horrors of the trench warfare, which was the hallmark of World War 1.[8]

The nearly a century of simmering tensions, and nationalistic fervor, between Serbia and Bosnia, was the background for the 1992 war. The Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadžić [9]stated “Our optimum is a Greater Serbia, and if not that, then a Federal Yugoslavia”[10]. The war in Bosnia escalated in April. On 3 April, the Battle of Kupres began between the JNA and a combined HV-HVO force that ended in a JNA victory. On 6 April Serb forces began shelling Sarajevo, and in the next two days crossed the Drina from Serbia proper and besieged Muslim-majority Zvornik, Višegrad and Foča. The war ended on 14th December 1995. The main belligerents were the forces of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and those of Herzeg-Bosnia and Republika Srpska, proto-states led and supplied by Croatia and Serbia, respectively.[11]

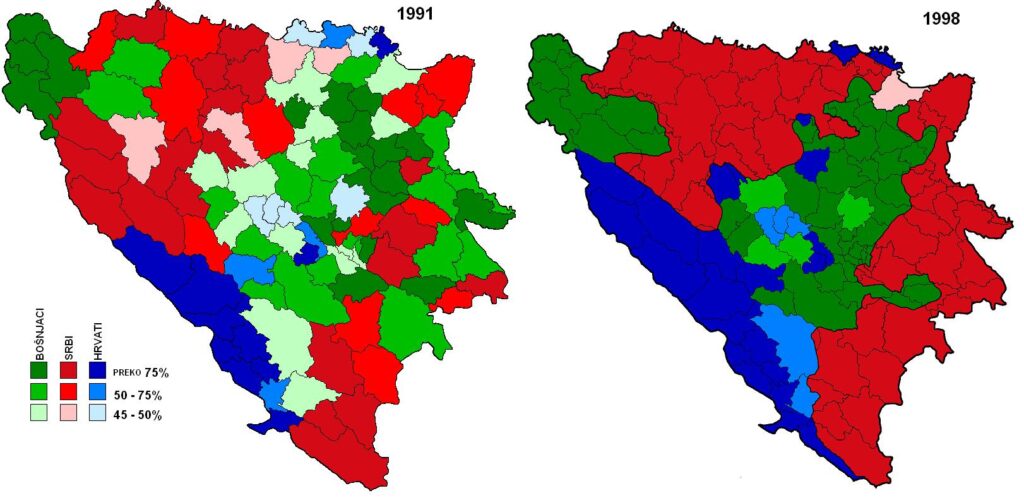

The war was part of the breakup of Yugoslavia. Following the Slovenian and Croatian secessions from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1991, the multi-ethnic Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina – which was inhabited by mainly Muslim Bosniaks (44%), mainly Orthodox Serbs (32.5%) and mainly Catholic Croats (17%) – passed a referendum for independence on 29 February 1992. Political representatives of the Bosnian Serbs boycotted the referendum, and rejected its outcome. Anticipating the outcome of the referendum boycotted by the majority of Bosnian Serbs, the Assembly of the Serb People in Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted the Constitution of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 28th February 1992. Following Bosnia and Herzegovina’s declaration of independence, which gained international recognition and following the withdrawal of Alija Izetbegović from the previously signed Cutileiro Plan,[12] which proposed a division of Bosnia into ethnic cantons, the Bosnian Serbs, led by Radovan Karadžić and supported by the Serbian government of Slobodan Milošević[13] and the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), mobilised their forces inside Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to secure ethnic Serb territory, then war soon spread across the country, accompanied by ethnic cleansing.

The conflict was initially between Yugoslav Army units in Bosnia which later transformed into the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) on the one side, and the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH), largely composed of Bosniaks, and the Croat forces in the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) on the other side. Tensions between Croats and Bosniaks increased throughout late 1992, resulting in the escalation of the Croat–Bosniak War in early 1993.[14] The Bosnian War was characterised by bitter fighting, indiscriminate shelling of cities and towns, ethnic cleansing, and systematic mass rape, mainly perpetrated by Serb,[15] and to a lesser extent, Croat[16] and Bosniak[17] forces. Events such as the Siege of Sarajevo and the Srebrenica massacre later became iconic of the conflict.

The Serbs, although initially militarily superior due to the weapons and resources provided by the JNA, eventually lost momentum as the Bosniaks and Croats allied against the Republika Srpska in 1994 with the creation of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina following the Washington agreement. Pakistan ignored the United Nation’s ban on supply of arms, and airlifted anti tank missiles to the Bosnian Muslims, while after the Srebrenica and Markale massacres, NATO intervened in 1995 with Operation Deliberate Force targeting the positions of the Army of the Republika Srpska, which proved key in ending the war.[18] The war ended after the signing of the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina in Paris on 14th December 1995. Peace negotiations were held in Dayton, Ohio, and were finalised on 21st November 1995.[19]

By early 2008, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia convicted forty-five Serbs, twelve Croats, and four Bosniaks of war crimes in connection with the war in Bosnia.[20]Estimates suggest around 100,000 people were killed during the war.[21] Over 2.2 million people were displaced,[22] making it the most devastating conflict in Europe since the end of World War II.[23] In addition, an estimated 12,000–50,000 women were raped, mainly carried out by Serb forces, with most of the victims being Bosniak women.[24]

The war led to the deaths of around 100,000 people. It also spurred the genocide of at least 80 percent Bosnian Muslims, also called Bosniaks,[25] who were brutally murdered in cold blood and constitutes the Bosnian Genocide, with cases still coming up at the International Court of Justice in the Hague.

While the Bosnian Genocide cannot be underplayed, as some nations have done and the judgments meted out has been the cause of great discontent, the Serbian planned and purposeful destruction of libraries and archives in Bosnia-Herzegovina has often been unnoticed or unreported, as if of no significance, whatsoever. [26] The concerted efforts by the Serbian leaders to totally eradicate the past written, glorious history of the Bosniaks was a special adjunctive mechanism in their intense efforts at ethnic cleansing of the origins, culture, religion and traditions of the Muslim Bosnians[27]. They used rampant and concentrated burning and destruction of Serbian historical tomes, books by burning down to cinders two major libraries in Sarajevo, Bosnia in the initial stages of the conflict, before the human genocide could even begin. Presently, years have passed since the beginning of the war in Bosnia. Amidst the reports of human suffering and atrocities, another tragic loss has gone largely unnoticed, the intended destruction of the written records of Bosnia’s past.

On 25th August 1992, Bosnia’s National and University Library, a handsome Moorish-revival building built in the 1890s on the Sarajevo riverfront, was shelled and burned. Before the fire, the library held 1.5 million volumes, including over 155,000 rare books and manuscripts; the country’s national archives; deposit copies of newspapers, periodicals and books published in Bosnia; and the collections of the University of Sarajevo. Bombarded with incendiary grenades from Serbian nationalist positions across the river, the library burned for three days; it was reduced to ashes with most of its contents. Braving a hail of sniper fire, librarians and citizen volunteers formed a human chain to pass books out of the burning building. Interviewed by ABC News, one of the “booksavers” said: “We managed to save just a few very precious books. Everything else burned down. And a lot of our heritage, national heritage, lay down there in ashes.” Aida Buturovic,[28] a librarian in the National Library’s exchanges section, was shot to death by a sniper while attempting to rescue books from the flames.[29] The result was, what a Council of Europe report has called “a cultural catastrophe.” In fact, that is describing the destruction, euphemistically. It was a “Cultural Genocide” as a prelude to the human genocide of Bosniaks. In addition, historic architecture, including 1200 mosques, 150 churches, 4 synagogues and over 1000 other monuments of culture, works of art, as well as cultural institutions, including major museums, libraries, archives and manuscript collections, have been systematically targeted and destroyed. The losses include not only the works of art, but also crucial documentation that might aid in their reconstruction. The international library community was approached to assist the recovery and reconstruct some of what has been lost and to rebuild the buildings and institutions that embody the Bosnian cultural heritage. The Sarajevo’s Oriental Institute[30], home to one of the largest collections of Islamic and Jewish manuscript texts and Ottoman documents in Southeastern Europe, was shelled with incendiary grenades and burned. Losses included 5,263 bound manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, and Adzamijski which was a Bosnian Slavic document, written in Arabic script); 7,000 Ottoman documents, primary source material for five centuries of Bosnia’s history; a collection of 19th century cadastral registers; and 200,000 other documents of the Ottoman era, including microfilm copies of originals in private hands or obtained on exchange from foreign institutions. The Institute’s collection of printed books, the most comprehensive library on its subject in the region, was also destroyed as was its catalog and all work in progress.[31]

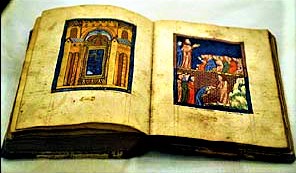

In each case, the library alone was targeted; adjacent buildings stand intact to this day. Serb nationalist leader Radovan Karadzic has denied his forces were responsible for the attacks, claiming the National Library had been set ablaze by the Muslims themselves “because they didn’t like its … architecture.” (New York Newsday, 30 November 1992) The 200,000-volume library of Bosnia’s National Museum (est. 1888) was successfully evacuated under shelling and sniper fire during the summer of 1992. Among the books rescued from the Museum was one of Bosnia’s greatest cultural treasures, the 14th-century Sarajevo Haggadah.

The work of Jewish calligraphers and illuminators in Islamic Spain, the manuscript was brought to Bosnia 500 years ago by Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. It entered the National Museum’s collection over a century ago. Successfully concealed from the Nazis by a courageous museum curator during World War II, the Sarajevo Haggadah[32] has now once again had to be hidden in a secret location.

The National Museum, meanwhile, has been badly hit. Shells have crashed through the roof and the skylights and all of its 300 windows have been shot out, as have the walls of several galleries. Parts of the Museum’s collection that could not be moved to safe stores remain in the building, exposed to further artillery attacks and to decay from exposure to the elements. Dr. Rizo Sijaric, the Museum’s Director[33], was killed by a grenade blast on 10 December 1993 while trying to arrange for plastic sheeting from UN relief agencies to cover some of the holes in the building. In April 1992, Serbian forces began bombarding the historic city of Mostar, the center of the country’s southwestern region, Herzegovina.

The Archives of Herzegovina, housing manuscripts and records documenting the region’s past since the medieval period, was repeatedly hit and suffered severe damage. Over 50,000 books were destroyed when the library of Mostar’s Roman Catholic archdiocese was struck by shells fired from artillery positions on the heights overlooking the city. Further tens of thousands of books and documents were exposed to fire and damp when shells smashed through the roof and windows of the Museum of Herzegovina. The University of Mostar Library was also hit and burned, along with a score of other libraries and archives at various locations in the city.[34]

Throughout Bosnia, libraries, archives, museums and cultural institutions have been targeted for destruction, in an attempt to eliminate the material evidence D1 books, documents and works of art D1 that could remind future generations that people of different ethnic and religious traditions once shared a common heritage in Bosnia. In the towns and villages of occupied Bosnia, communal records (cadastral registers, waqf documents, parish records) of more than 800 Muslim and Bosnian Croat (Catholic) communities have been torched by Serb nationalist forces as part of “ethnic cleansing” campaigns. While the destruction of a community’s institutions and records is, in the first instance, part of a strategy of intimidation aimed at driving out members of the targeted group, it also serves a long-term goal.

These records were proof that non-Serbs once resided and owned property in that place, that they had historical roots there. By burning the documents, by razing mosques and Catholic churches and bulldozing the graveyards, the nationalist forces who have now taken over these towns and villages are trying to insure themselves against any future claims by the people they have driven out and dispossessed, as in Palestine[35].

Other Bosnians, however, remain determined to preserve their country’s historic ideal of a multicultural, tolerant society and the institutions that enshrine its collective memory. Surviving staff members of the National and University Library, Serbs and Croats as well as Muslims, are still at work in Sarajevo. An estimated 10% of the Library’s collection was saved, as were computer tapes containing cataloguing records for at least some of the items that perished in the fire. In temporary quarters, 42 librarians, out of a pre-war staff of 108. are preparing inventories, undertaking what conservation measures are possible under current conditions, keeping track of titles published in Sarajevo since April 1992, and planning for the post-war reconstruction of their institution. They are also trying to serve the needs of 850 faculty members and the 4,500 students still studying at the University of Sarajevo; 70 students have completed work for doctoral degrees since the beginning of the siege.

The librarians and research staff of Sarajevo’s Oriental Institute have also decided to carry on, despite the nearly total loss of their Institute’s collections. In temporary quarters, they have been holding seminars and symposia to share their research, reconstructed from notes kept at home, and making plans for the Institute’s future. They have issued a call for moral and material support from their colleagues throughout the world.

Response thus far by international agencies, institutions and professional organizations has been only modestly encouraging. UNESCO has given its endorsement to the rebuilding of the National Library, has sponsored a number of meetings to discuss the project, and has set up an office in Sarajevo. However, few books and little aid has actually reached Sarajevo thus far. The Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly, a human rights group based in Prague, has called on its affiliates to assist Bosnia’s National Library and has established collection sites for donated materials in Europe.[36] The Turkish National Library has undertaken to locate Bosnia-related materials in its own collections, with the goal of making copies available when Bosnia’s National Library is rebuilt, and has issued a call to national and academic libraries elsewhere urging them to join the effort.[37]

The Bottom Line is that the burning of libraries and archives cannot be construed as a mere expression of one side’s views in a political dispute. It is also not merely one of the regrettable calamities of war. It is a crime against humanity and a violation of international laws and conventions. The latter include the 1931 Athens Charter, the 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, the 1964 Venice Charter, and the 1977 Protocols I and II Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, all of which were ratified by the government of the former Yugoslavia and remain legally binding upon its successor states.[38]

Presently the prosecution of crimes against culture remains one of the urgent tasks facing the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and deserves full support. But we can also play an active part, in our professional capacities, to assist in the task of rebuilding the libraries and cultural heritage of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In addition to the examples given above, there are also other creative ways to use our collective expertise and resources. Although the scale of destruction is unprecedented, not all has been lost in Bosnia and some of what has been destroyed may be recoverable.

Sarajevo’s Gazi Husrev Beg Library[39], one of Bosnia’s pre-eminent manuscript libraries established in 1537, was shelled in May 1992, but most of its collection has been saved. That collection, along with other caches of rescued but endangered materials, including most the holdings of the Archives of Herzegovina in Mostar, requires the attention of conservation professionals. Training internships as well as technical and material assistance to our Bosnian colleagues, who face the task of caring for, preserving and restoring these precious items.

Of the manuscripts and documents destroyed in the fire that consumed the Oriental Institute, many had been filmed before the war as part of research and exchange projects. Copies of those microfilms, now dispersed in foreign libraries and research institutes, can be collected, with the help of foreign librarians and scholars, to form the core of a rebuilt Institute.

In addition to the burning of libraries, the most grievous loss has been the systematic destruction of historic architecture and works of art in Bosnia. Bosnians are anxious to rebuild at least a representative portion of these monuments of their country’s multi-ethnic heritage. This will require not only financial support and technical expertise, but also documentation, much of which now survives only outside of Bosnia. Finally, on the point of preservation of cultural heritage, it must also include monuments and statues of colonialists, slavers, imperialists and other oppression from the past. This is a particular challenge in South Africa, where rioters consisting mainly of students, have protested against the continuous and ongoing displays of such effigies and monuments, glorifying the White oppressors against the indigenous people. These protests have resulted in many universities and institutes removing the statues of such individuals, globally. This has also happened in Britain and in the Middle East. The question is how will future generations know of the heritage of our past, be it of the oppressors, tyrants and other miscreants in history of a nation. If the Voortrekker Monument[40] in South Africa is destroyed, then the oppressive heritage against the Black people will be lost forever.[41] While the South African Constitution of 1997[42] has the Heritage Act[43] , protecting and preserving such structures, statues of imperialists such as Cecil John Rhodes[44] has been vandalised and subsequently removed, by the university administration, on 09th April 2015, from the grounds of the internationally renowned, University of Cape Town[45]

References:

[1] https://www.historynet.com/fourth-crusade-conquest-of-constantinople.htm

[2] https://www.bing.com/search?q=when+did+the+bosnia+conflict+start&cvid=769a16fd6e6f42d0b19971594f3f98c5&aqs=edge..69i57.12835j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531#:~:text=The%20Bosnian%20War%20(%20Serbo,earlier%20in%20the%20year.

[3] https://www.bing.com/search?q=when+did+the+bosnia+conflict+start&cvid=769a16fd6e6f42d0b19971594f3f98c5&aqs=edge..69i57.12835j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531#:~:text=the%20Bosnian%20crisis%3F-,The%20Bosnian%20Crisis%20was%20sparked%20by%20anger%20over%20the%20annexation,the%20agreement%20of%20the%20rest%20of%20Europe%20(Treaty%20of%20Berlin).,-The%20Bosnian%20Crisis

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Berlin_(1878)#:~:text=The%20Treaty%20of%20Berlin%20accorded%20special%20legal%20status,recognize%20non-Christians%20%28Jews%20and%20Muslims%29%20as%20full%20citizens.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Izvolsky

[6] https://historylearning.com/world-war-one/causes-of-world-war-one/bosnian-crisis/

[7] https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=black+hand+secret+society&qpvt=black+hand+secret+society&FORM=IGRE

[8] https://historylearning.com/world-war-one/causes-of-world-war-one/sarajevo-assassination-1914/

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radovan_Karad%C5%BEi%C4%87

[10] https://www.bing.com/search?q=when+did+the+bosnia+conflict+start&cvid=769a16fd6e6f42d0b19971594f3f98c5&aqs=edge..69i57.12835j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531#:~:text=Bosnian%20Serb%20political,the%20International%20C%E2%80%A6

[11] https://web.archive.org/web/20120321165225/http://cmiskp.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.asp?action=html&documentId=820323&portal=hbkm&source=externalbydocnumber&table=F69A27FD8FB86142BF01C1166DEA398649

[12] https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-resolution/134

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/mar/13/guardianobituaries.warcrimes

[14] https://web.archive.org/web/20120321165225/http://cmiskp.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.asp?action=html&documentId=820323&portal=hbkm&source=externalbydocnumber&table=F69A27FD8FB86142BF01C1166DEA398649

[15] Simons, Marlise (20 March 2019). “Radovan Karadzic Sentenced to Life for Bosnian War Crimes”. The New York Times.

[16] https://www.ted.com/talks/ziyah_gafic_everyday_objects_tragic_histories

[17] https://web.archive.org/web/20120321165225/http://cmiskp.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.asp?action=html&documentId=820323&portal=hbkm&source=externalbydocnumber&table=F69A27FD8FB86142BF01C1166DEA398649

[18] United Nations General Assembly Session 47 Resolution 121. The situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina: resolution / adopted by the General Assembly A/RES/47/121 18 December 1992.

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bosnian_genocide#:~:text=The%20International%20Criminal%20Tribunal%20for%20the%20Former%20Yugoslavia%20found,IT%2D98%2D33%20(2004)%20ICTY%207%20(19%20April%202004)

[20] https://www.un.org/icty/krstic/Appeal/judgement/krs-aj040419e.pdf

[21] Staff. Momcilo Krajisnik convicted of crimes against humanity, acquitted of genocide and complicity in genocide, A press release by the ICTY in The Hague, 27 September 2006 JP/MOW/1115e

[22] Irwin, Rachel. 13 December 2012. “Genocide Conviction for Serb General Tolimir Archived 8 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine.” Global Voices: Europe & Eurasia (769). UK: Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

[23] http://iwpr.net/report-news/genocide-conviction-serb-general-tolimir

[24] Schultz, Teri (22 November 2017). “‘Butcher of Bosnia’ Ratko Mladic Guilty of Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity”. NPR.org.

[25] https://www.bing.com/search?q=when+did+the+bosnia+conflict+start&cvid=769a16fd6e6f42d0b19971594f3f98c5&aqs=edge..69i57.12835j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531#:~:text=1992-,The%20Bosnian%20War%20began%20in%201992%20and%20lasted%20until%201995,of%20at%20least%2080%20percent%20Bosnian%20Muslims%2C%20also%20called%20Bosniaks.,-What%20Was%20the

[26] https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/19/resources/6408

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam_in_Bosnia_and_Herzegovina

[28] https://www.bing.com/search?q=Aida+Buturovic%2C+a+librarian+in+the+National+Library%E2%80%99s&aqs=edge..69i57.11499897j0j4&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531&ntref=1#:~:text=Date-,Among%20the%20human%20casualties%20was%20Aida%20Buturovic%C2%B4%2C%20a%20thirty%2Dtwo%2Dyear%2Dold%20librarian%20in%20the%20National%20Library%E2%80%99s%20international%20exchanges%20section.%20She%20was%20killed%20by%20a%20mortar%20shell%20as%20she%20tried%20to%20make%20her%20way%20home%20from%20the%20library.,-Andr%C3%A1s%20J.%20Riedlmayer

[29] https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla61/61-riea.htm

[30] https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=sarajevo%27s+oriental+institute+picture&qpvt=Sarajevo%27s+Oriental+Institute+picture&FORM=IGRE

[31] https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla61/61-riea.htm#:~:text=Three%20months%20earlier,work%20in%20progress.

[32] https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=sarajevo+haggadah+photos&qpvt=sarajevo+haggadah+photos&FORM=IGRE

[33] https://species.wikimedia.org/wiki/Rizo_Sijari%C4%87

[34] https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla61/61-riea.htm#:~:text=In%20each%20case,in%20the%20city.

[35] https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1973/8/7/the-dispossessed-in-palestine-pbbbefore-the/

[36] https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla61/61-riea.htm#:~:text=The%20Helsinki%20Citizens%27%20Assembly%2C%20a%20human%20rights%20group%20based%20in%20Prague%2C%20has%20called%20on%20its%20affiliates%20to%20assist%20Bosnia%27s%20National%20Library%20and%20has%20established%20collection%20sites%20for%20donated%20materials%20in%20Europe.

[37] https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla61/61-riea.htm#:~:text=The%20Turkish%20National%20Library%20has%20undertaken%20to%20locate%20Bosnia%2Drelated%20materials%20in%20its%20own%20collections%20%2D%2D%20with%20the%20goal%20of%20making%20copies%20available%20when%20Bosnia%27s%20National%20Library%20is%20rebuilt%20%2D%2D%20and%20has%20issued%20a%20call%20to%20national%20and%20academic%20libraries%20elsewhere%20urging%20them%20to%20join%20the%20effort.

[38] https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla61/61-riea.htm#:~:text=The%20debates%20in,its%20successor%20states.

[39] https://unsa.ba/en/about-university/unsa-sarajevo/gazi-husrev-beys-library

[41] https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/voortrekker-monument

[42] https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/Constitution-Republic-South-Africa-1996-1#:~:text=The%20Constitution%20of%20the%20Republic%20of%20South%20Africa%2C,action%20can%20supersede%20the%20provisions%20of%20the%20Constitution.

[43] https://www.gov.za/documents/national-heritage-resources-act

[44] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/cecil-john-rhodes

[45] https://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/rhodes-statue-removed-uct

______________________________________________

Read: Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 4

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Balkans, Books, Bosnia, Christianity, Ethnic Cleansing, History, Islam, Literacy, Literature, Muslims

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 31 Jan 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Destruction of Literary Heritage as a Tool in Ethnic Cleansing (Part 3), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.