Nearly 12 years ago WikiLeaks published the Afghan War Diary, one of the biggest leaks in US military history. More documents would folliow, exposing state secrets and allowing journalists to scrutinise and hold politicians to account.

To avoid extradition to the States to face espionage charges, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange took refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London for seven years, before Ecuador turned him over to Britain in 2019. He is currently in Belmarsh Prison in south-east London.

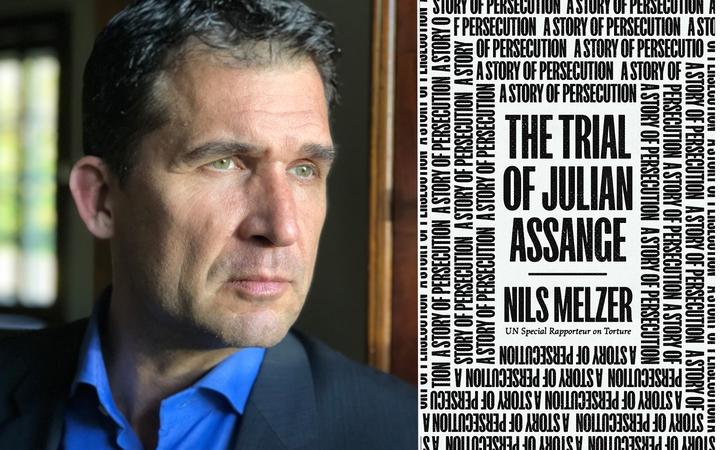

Photo: Eugene Jarecki / Supplied

Nils Melzer, the current UN Special Rapporteur on Torture initially declined to get involved in Assange’s case. But as he writes in his new book The Trial of Julian Assange, when he started to look closely at the facts he found Assange to be a victim of political persecution.

He first met Assange in May 2019 when he visited him with two medical specialists at Belmarsh, four weeks after he had been arrested. The team were there to investigate claims of torture.

When Assange name first crossed his desk, he says his reaction was visceral – he dismissed Assange as a rapist, a narcissist and a hacker, based on media reports of his case. Assange’s lawyers had contacted him in December 2018 when he was still in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London asking for intervention under the conditions of the Anti-Torture Convention as his living conditions were considered inhumane.

It was only after looking at the medical reports that he acted and looked deeper into the case.

“I didn’t know Mr Assange,” he told Saturday Morning. “I had never analysed the case and I was under the same impression that many others are still under today from those narratives that had been spread in the press for 10 years about him – being suspected of rape, being a coward hiding in the embassy, a self-centred narcissist. I had also sub-consciously absorbed this narrative.

“So, when his lawyers reached out to me as the mandated UN human rights expert I had been so affected by this narrative that I was unable to objectively look at the case. I initially declined to look at it.

“It was only when his lawyers came back three months later and said they were afraid they might be imminently expelled from the embassy and sent to the US on espionage charges that they sent along a couple of pieces of evidence, including some medical opinion by Dr Sandra Crosby, who’s not an Assange activist. She’s a well-known independent medical expert in the US who had visited Guantanamo… and had specialised in examining torture victims for all of her career. She had visited Assange and had come to the conclusion that his living conditions had indeed breached the Convention against torture.”

On 8 April 2019, he requested that the UK and Ecuadorian government freeze the situation until he could visit and carry out an investigation. On 11 April Assange was expelled from the embassy and taken into custody without due process.

“I might even have accelerated this process. I don’t know that for sure,” he says.

Melzer has no binding authority on governments and can only point out allegations of torture and make recommendations to governments, but he was surprised at the UK government’s lack of engagement with him over Assange.

The UN Human Rights Council has an expectation that governments co-operate with their mandate, but cannot compel acfion. The Assange cases highlighted its lack of teeth, he says.

“The reaction of the states in the Assange case actually prompted me to conduct a wider analysis of the effectiveness of my interventions more generally and indeed about nine of the 10 requests don’t receive adequate responses where you could actually resolve a case and provide protection to a person,” Melzer says.

Assange’s position has been widely misunderstood due to a media narrative that suggested Assange had voluntarily remained at the embassy. His position had been ridiculed as someone paranoid of being arrested, as well as being portrayed as a person hiding to avoid justice in the Swedish courts on rape charges, Melzer says.

However, Assange felt compelled to stay at the London Embassy due to threats of rights violations if he left, Melzer points out.

In December last year the High Court in London ruled he could be extradited to the US to face charges under the Espionage Act, after a judge accepted assurances authorities would take measures to reduce his risk of suicide and wouldn’t impose restrictive prison conditions on him.

He faces a sentence of up to 170 years in prison.

“Espionage Act has the advantage for the US that it does not allow any form of defence on the part of the accused,” Melzer says.

“As soon as the accused is proven to have disclosed classified information protected by the Espionage Act, then he’s basically to be convicted for espionage.

“So, then he can’t raise a defence of public interest for example, saying ‘well the information I disclosed is evidence for serious misconduct if not war crimes on the part of the authorities and therefore cannot be protected by secrecy.

“That’s a defence that’s not allowed under the Espionage Act and that’s the main reason why they would want to accuse him and prosecute him under that piece of legislation, because otherwise Julian Assange would clearly start unpacking the content of the information he disclosed and the fact that no one has ever been prosecuted for those very serious crimes, and that would clearly make it very difficult for the US to maintain a viable case.”

Contrary to the High Court judge’s interpretation there were no substantive assurances given that Assange would be treated humanely by the US, he says.

“They have promised that they would not detain Julian Assange in a very specific supermax prison in Florence, Colorado that was used in eventual hearings as an example of particularly harsh conditions. But the United States has dozens of other supermax prisons… they have not been excluded in those assurances.”

Assange faces up to 15 years in strict solitary confinement while his legal team fights for him to serve his time in Australia, if the Australia government accepts this arrangement, Melzer adds.

For Melzer there has been so much misinformation released about Assange and WikiLeaks that it’s important to distinguish between facts and false narratives circulating in media.

The US has never proven that lives of military personnel were put under threat because of WikiLeaks, he points out. Much of those false accusations serve to mask the true intent of the US government’s actions against WikiLeaks.

“What was so dangerous is the methodology of WikiLeaks,” Melzer says..

“It’s not the actual content of the actual information that has been disclosed, but the mechanism that has been developed – that was revolutionary.

“We’ve had before massive leaks, such as that of the Pentagon Papers, for example. But because there was no internet at the time there was a natural limit to the amount of information you could leak and make available to the public. Through the WikiLeaks platform that allows whistleblowers to remain anonymous and at the same time leak millions of pages of secret information from all over the world.

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange prepares to speak to the media in England, on December, 2010. Photo: AFP / FILE

“If that replicates, if that would proliferate as a model and a few years later you might have 20,000 WikiLeaks for all over the world, well, that would be the end of the business model of governments based on secrecy and impunity.

“That’s what the US government and their allies are afraid of and they’re setting on example with the Assange’s case to deter others because the actual real-world damage created by those specific publications… there has been no evidence that there has been more than embarrassment for the US.”

Melzer accepts the need in liberal democracies to create protective space for negotiations and bilateral dialogue between states and institution, but cautions there is an important distinction between confidentiality and secrecy..

“Confidentiality does not remove the content of those discussions from legal oversight should there be any crime committed behind the vale of secrecy.”

He says there cannot be any justification for removing any part of governance for public oversight, at least through an intermediary like the judiciary.

Much has also been said about how irresponsible WikiLeaks had been dumping millions of pages of diplomatic papers into the public domain without redaction or curation. Melzer points out Assange warned the US about the file dump and suggested co-operative ways of mitigating threats.

“WikiLeaks actually went to great lengths ensuring that there was a proper redaction and risk reduction,’ he says.

“The publication of unredacted diplomatic cables for example was not something that came from WikiLeaks as the first publisher, but was apparently two Guardian journalists who published a book and in that book they published the passwords that they had been given by WikiLeaks to work on those unredacted files. Through that password those unredacted files that had been stored on the internet encrypted were made available to the public and only after that happened WikiLeaks decided to also publish files unredacted.”

Assange has been in Belmarsh Prison for three years now, with reports of his mental health deteriorating. Melzer says when he visited him he did not expect to find torture.

“I expected to find someone who was stressed out, who had some medical problems,” he says.

“He immediately reminded me of political prisoners I had visited around the world… He also reminded me, from his behavioural pattern, his body language, that really reflected the findings of the doctors that he had been exposed to enormous psychological pressure.”

His answers to questions were unfocused, Melzer says.

There were signs of autism, something that has been mischaracterised by some as evidence of narcissistic tendencies.

“I do believe the diagnosis of Aspergers, a slight form of autism, is probably the most appropriate way to describe him – as someone who is extremely focused on his own thoughts and you have to verbalise what you want to know from him, otherwise he will go off in his own thoughts.”

Assange never fully sleeps and has constant thoughts of suicide, suffering several psychological breakdowns and a very deep depression, he says.

“When you look at psychological torture you have to look at how the identity or the stability of someone’s psyche has been affected by his isolation the constant pressure he’s been under, the constant threats he’s been under, the separation from positive influences – all of these factors are being used quite deliberately in psychological torture to break down someone’s mental resistance and confuse him.”

Melzer says his investigation was objective, neutral and impartial, but when he found out Assange was subject to torture and ill-treatment, his job has been to defend him and call on states to respect legal obligations.

Western democracies such as Sweden and the UK rejecting those obligations has frustrated Melzer. He says he’s been so outspoken about the case because of the way political interests have been allowed to neutralise the judiciary and legal process.

Assange’s case, he says, provides evidence of a wider systemic failure.

“They simply refused to engage in a dialogue with me or to even provide any counter evidence of why my interpretation of those facts would be wrong and that really is something that I would not expected.”

There is no sign US President Joe Biden will show leniency to Assange, with the Democratic Party still holding Assange responsibly for Hilary Clinton losing the 2017 election on WikiLeaks’ release of internal party emails prior to the vote and Russian hacking. Melzer says that has been another highly-dubious narrative used to corner Assange.

“I’m not trying to defend Assange. I’m not his lawyer,” he says.

“I’m trying to defend human rights and the rule of law. If states have any crime that they can indict Julian Assange and have evidence, by all means he has to stand trial like everybody else. My problem simply is, if you look at the US indictment, 17 of those 18 points refer to receiving and disclosing classified national security information. Julian Assange is not American.

“He has no duty or allegiance to the Americans, no contractual obligations. He was not in the US during the release of this information. That’s what investigative journalists do. The information that he published was in large parts in the public interest.”

The eighteenth point refers to a hacking charge. However, Melzer says Assange actually only helped the source of the leaks, Chelsea Manning, cover her tracks to avoid detection. “It was not to get access to information or steal information, but to do source protection… which is something that journalists do all the time with their sources.”

The real purpose behind Assange’s imprisonment and trial is to deter journalists from exposing state crimes and intimidate them into not publishing material that challenges dominant political interests, he says.

“What exactly are we accusing Julian Assange of? Even the rape allegations were dropped by the Swedish authorities… because they had not even sufficient evidence to press charges… That’s why I came to the conclusion that the purpose here is not prosecution for any serious crime. It is to deter journalists from doing what he has done.”