Imperial, Colonial Thieves: The Annihilation of the Kingdom of Benin and Pillaging of the Royal Palace by British Soldiers (Part 3)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 14 Mar 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“It need scarcely be said that at the first sight of these remarkable works of art we were at once astounded at such an unexpected find, and puzzled to account for so highly developed an art among a race so entirely barbarous.”

— British Museum curator Sir Charles Hercules Read [1]

A Benin Plaque Cast in brass in the 16th century: The Oba with Europeans ripped from the Palace of the Kingdom of Benin

12 Mar 2022 – A frenzied and savage mob of 1200 British soldiers, empowered and fired up with a singular aim of revenge “against the barbarous savages”, landed on the serene coast line of Nigeria, on 09th February 1897. This was the beginning of a massive attack on and the ruthless invasion of the Kingdom of Benin. The British invasion force consisted of Royal Marines, sailors and Niger Coast Protectorate Forces was organised into three columns: the ‘Sapoba’, ‘ Gwato ‘ and ‘Main’ columns, under the supreme command of Sir Harry Rawson’s troops who captured bayonetted citizens, including women and children and sacked Benin City, ending the Kingdom of Benin, which was eventually absorbed into colonial Nigeria[2] in the late 19th century. The magnificent treasures of the Kingdom of Benin were violently stripped from the walls of the palace, looted and transported to Britain.

The plaque illustrated above is about 60 cm. is dominated by the majestic figure of the Oba himself. Its colour strikes the observer as coppery rather than brassy, and there are five figures on it: three Africans and two Europeans. In the centre, in the proudest relief and looking straight out at us, is the Oba. He is on his throne wearing a high helmet-like crown. His neck is completely invisible, adorned by a series of large rings runs from his shoulder right the way up to his lower lip. In his right hand he holds up a ceremonial axe. To either side of the Oba kneel two court functionaries, dressed very like him but with plainer headdresses and fewer neck-rings. They wear belts hung with small crocodile heads, and these were the emblem of those authorised to conduct business with the Europeans. And the Europeans are present, or at least part of them. Against the patterned background, we can see floating the heads and shoulders of two tiny Europeans.[3]

Like some West African music, the Benin brass plaques are principally concerned with praising the Oba[4]. They were nailed to the walls of his palace, similar to the tapestries in a European context. These displays allowed the visitor to Benin, at the time, prior to 1897, to admire not only the achievements of the ruler and the wealth of the kingdom, but also the creative work of the superb craftsmanship in brass, of the Kingdom of Benin, while the European courts were still creating works of art in paint for their courts.

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as the Edo Kingdom, or the Benin Empire was a kingdom in what is now in southwestern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern Republic of Benin, which was historically known as Dahomey from the 17th century until 1975. The Kingdom of Benin’s capital was Edo, now known as Benin City in Edo state, Nigeria. The Benin Kingdom was “one of the oldest and most developed states in the coastal hinterland of West Africa”. It was formed around the 11th century AD,[5] and lasted until it was annexed by the British Empire in 1897, after a violent destruction, as was the typical modus operandi of the imperial forces, against rebellion in their colonies.

In early history, by the 1st century BC, the Benin territory was partially agricultural and it became primarily agricultural by around 500 AD, but hunting and gathering still remained important. Also by 500 AD, iron was in use by the inhabitants of the Benin territory.[6]

Benin City sprang up by around 1000, in a forest that could be easily defended. The dense vegetation and narrow paths made the city easy to defend against attacks. The rainforest, which Benin City is situated in, helped in the development of the city because of its vast resources. These were fish from rivers and creeks, animals to hunt, leaves for roofing, plants for medicine, ivory for carving and trading, and wood for boat building, which could easily be used by the citizens.. However, domesticated animals, from the forest and surrounding areas, could not survive, due to a disease spread by tsetse flies; after centuries of exposure, some animals, such as cattle and goats, developed a resistance to the disease.[7]

The original name of the kingdom of Benin, at its creation sometime in the first millennium CE, was Igodomigodo, as its inhabitants called it. Their ruler was called Ogiso, the ruler of the sky.[8] Nearly 36 known Ogiso are accounted for as rulers of this initial incarnation of the state.

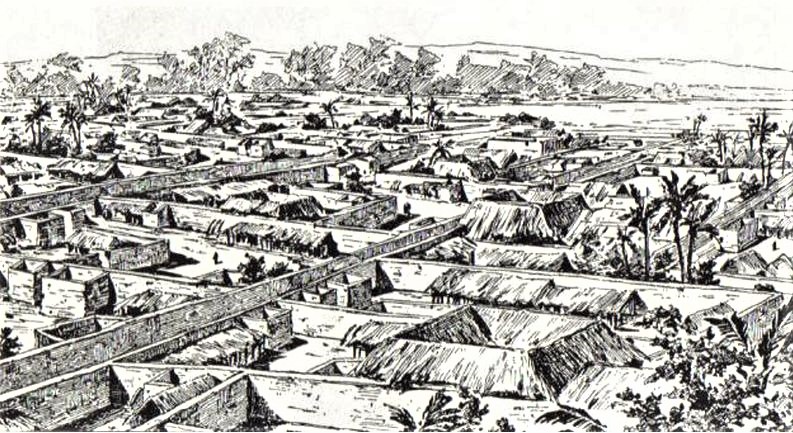

Depiction of Benin City by a Dutch illustrator in 1668. The wall-like structure in the centre probably represents the walls of Benin.

The Walls of Benin are a series of earthworks made up of banks and ditches, called Iya in the Edo language in the area around present-day Benin City, the capital of present-day Edo, Nigeria. They consist of 15 km of city Iya and an estimated 16,000 km in the rural area around Benin.[9] Some estimates suggest that the walls of Benin may have been constructed between the thirteenth and mid-fifteenth century CE[10] and others suggest that the walls of Benin, in the Esan region, may have been constructed during the first millennium AD.[11] The Benin City walls have been known to Westerners since around 1500. The Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pereira, briefly described the walls during his travels. Another description given around 1600, one hundred years after Pereira’s description, is by the Dutch explorer Dierick Ruiters.[12] Ruiters’ account of the walls is as follows: “At the gate where I entered on horseback, I saw a very high bulwark, very thick of earth, with a very deep broad ditch, but it was dry, and full of high trees. That gate is a reasonable good gate, made of wood in their manner, which is to be shut, and there always there is watch holden.[13] Pereira’s account of the walls is as follows: “This city is about a league long from gate to gate; it has no wall but is surrounded by a large moat, very wide and deep, which suffices for its defence.[14] The archaeologist Graham Connah suggests that Pereira was mistaken with his description by saying that there was no wall. Connah says, “[Pereira] considered that a bank of earth was not a wall in the sense of the Europe of his day.”[15] Estimates for the initial construction of the walls range from the first millennium to the mid-fifteenth century. According to Connah, oral tradition and travelers’ accounts suggest a construction date of 1450–1500.[16] It has been estimated that, assuming a ten-hour work day, a labour force of 5,000 men could have completed the walls within 97 days, or by 2,421 men in 200 days. However, these estimates have been criticised for not taking into account the time it would have taken to extract earth from an ever deepening hole and the time it would have taken to heap the earth into a high bank.[17] It is unknown whether slavery or some other type of labour was used in the construction of the walls. It is also recored in oral history hat the Benin was involved in a prolific slve trade of its dissidents and individuals whose spouse were fancied by the king. Essentially, the Kings of Benin Empire, sold off its own people into foreign slavery generating good income for the kingdom. This is regarding as one of the mechanisms to account for the economic empowerment of the kingdom, until slavery was abolished. However, perhaps slave labour was used as the walls were built of a ditch and dike structure. The ditch dug to form an inner moat with the excavated earth used to form the exterior rampart. The Benin Walls were partially demolished by the British in 1897 during the punitive expedition. Scattered pieces of the structure remain in Edo, with the vast majority of them being used by the locals for building purposes. What remains of the wall itself continues to be torn down for real estate developments in Nigeria.[18]

They extend for some 16,000 km in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They cover 6,500 square kilometres and were all dug by the Edo people. In all, they are four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops. They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet often referred to as the “Great Walls of Benin”[19]. Ethnomathematician Ron Eglash[20] has discussed the planned layout of the city using fractals as the basis, not only in the city itself and the villages but even in the rooms of houses. He commented that “When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.”[21]

Excavations at Benin City have revealed that it was already flourishing around 1200-1300 CE.[22] In 1440, Oba Ewuare, also known as Ewuare the Great, came to power and expanded the borders of the former city-state. It was only at this time that the administrative centre of the kingdom began to be referred to as Ubinu after the Portuguese word and corrupted to Bini by the Itsekhiri, Urhobo and Edo who all lived together in the royal administrative centre of the kingdom. The Portuguese who arrived in an expedition led by João Afonso de Aveiro in 1485 would refer to it as Benin and the centre would become known as Benin City.[23]

The Kingdom of Benin eventually gained political strength and ascendancy over much of what is now mid-western Nigeria. Benin’s wealth grew through its extensive trade, especially with the Portuguese. European traders were keen to acquire Benin’s art, gold, ivory and pepper. In the late seventeenth century, the kingdom temporarily declined following a major civil war and disputes over the kingship.[24]

There are numerous, important historical figures of ancient Benin Kingdom.[25] Queen Idia was the wife of Oba Ozolua, the Oba who reigned in about 1481 AD. She was a famous warrior who received much of the credit for the victories of her son as his political counsel, together with her mystical powers and medicinal knowledge, were viewed as critical elements of Esigie’s success on the battlefield. Queen Idia became more popular when an ivory carving of her face was adopted as the symbol of FESTAC in 1977,[26]

Emotan was trader who sold her wares at the exact point where her statue now stands. She was historically credited with setting up the first primary school in the kingdom and saving the monarchy during one of its lowest moments. She helped the Oba Ewuare in reclaiming the throne from his usurper brother, Oba Uwaifiokun who reigned about 1432 AD.[27]

Queen Iden is yet another heroine whose sacrifice helped shape Benin Kingdom. She was the queen during the reign of Oba Ewuape in about 1700 AD. She is known to have volunteered herself as a sacrificial lamb for the welfare of her husband and that of the entire kingdom after she consulted the oracle and was informed that human sacrifice would be needed to appease the gods and restore peace and unity in the kingdom.[28]

General Asoro the Warrior was the sword bearer to King Ovonramwen, the Oba of Benin, in 1897. He participated in the defence of Benin during the 1897 expedition, engaging the British expeditionary force sent to capture the Oba. A quote uttered by the general that “no other person[should dare pass this road except the Oba” .The kpon Oba was later translated to “SAKPONBA”, which a well-known road in Benin was named after.[29]

Chief Obasogie was not just an outstanding Benin warrior of old who defended the kingdom against external invasion but also a highly talented blacksmith and sculptor.[30]

Forty-one female skeletons thrown into a pit were discovered by the archaeologist Graham Connah. These findings indicate that human sacrifice or murder of criminals took place in Benin in the 13th century AD[31]. From the early days, human sacrifices were a part of the state religion. But many of the sensationalist accounts of the sacrifices, says historian J.D. Graham, are exaggerated or based on rumour and speculation. He says that all of the evidence “points to a limited, ritual custom of human sacrifice, many of the written accounts referring to the human sacrifices describe them as actually being executed criminals.[32] Humans were sacrificed in an annual ritual in honour of the god of iron, where warriors from Benin City would perform an acrobatic dance while suspended from the trees. The ritual recalled a mythical war against the sky.[33] Sacrifices of a man, a woman, a goat, a cow and a ram were also made to a god quite literally called “the king of death.” The god, named Ogiuwu, was worshipped at a special altar in the centre of Benin City. There were two separate annual series of rites that honoured past Obas. Sacrifices were performed every fifth day. At the end of each series of rites, the current Oba’s own father was honoured with a public festival. During the festival, twelve criminals, chosen from a prison where the worst criminals were held, were sacrificed. By the end of the eighteenth century, three to four people were sacrificed at the mouth of the Benin River annually, to attract European trade.[34]

The monarchy of Benin was hereditary; the eldest son was to become the new Oba. In order to validate the succession of the kingship, the eldest son had to bury his father and perform elaborate rituals. If the eldest son failed to complete these tasks, the eldest son might be disqualified from becoming king. After the son was installed as king, his mother – after having been invested with the title of Iyobam was transferred to a palace just outside Benin City, in a place called Uselu. The mother held a considerable amount of power; she was, however, never allowed to meet her son, who was now a divine ruler, again for fear of casting evil spirits on the king.[35] In Benin, the Oba was seen as divine. The Oba’s divinity and sacredness was the focal point of the kingship. The Oba was shrouded in mystery; he only left his palace on ceremonial occasions. It was previously punishable by death to assert that the Oba performed human acts, such as eating, sleeping, dying or washing. The Oba was also credited with having magical powers. The Oba had become the mount of power within the region. Oba Ewuare, the first Golden Age Oba, is credited with turning Benin City into a city-state from a military fortress built by the Ogisos, protected by moats and walls. It was from this bastion that he launched his military campaigns and began the expansion of the kingdom from the Edo-speaking heartlands. A series of walls marked the incremental growth of the sacred city from 850 AD until its decline in the 16th century. To enclose his palace he commanded the building of Benin’s inner wall, an 11-kilometre-long, earthen rampart girded by a moat 6 m deep. This was excavated in the early 1960s by Graham Connah. Connah estimated that its construction if spread out over five dry seasons, would have required a workforce of 1,000 laborers working ten hours a day seven days a week[citation needed]. Ewuare also added great thoroughfares and erected nine fortified gateways.

Excavations also uncovered a rural network of earthen walls 6,000 to 13,000 km long that would have taken an estimated 150 million man-hours to build and must have taken hundreds of years to build. These were apparently raised to mark out territories for towns and cities. Thirteen years after Ewuare’s death, tales of Benin’s splendors lured more Portuguese traders to the city gates. At its height, Benin dominated trade along the entire coastline from the Western Niger Delta, through Lagos to the kingdom of Great Accra (modern-day Ghana). It was for this reason that this coastline was named the Bight of Benin. The present-day Republic of Benin, decided to choose the name of this bight as the name of its country. Benin ruled over the tribes of the Niger Delta including the Western Igbo, Ijaw, Itshekiri, Ika, Isoko and Urhobo amongst others. It also held sway over the Eastern Yoruba tribes of Ondo, Ekiti, Mahin/Ugbo, and Ijebu. It also conquered what eventually became the city of Lagos hundreds of years before the British took over in 1861.

Recently, the campaign to repatriate the Benin Bronzes, actually crafted from brass. imparted some recognition and well-earned fame to the creative talents of the craftsmen of ancient Benion. The state developed an advanced artistic culture, especially in its famous artifacts of bronze, iron and ivory. These include bronze wall plaques and life-sized bronze heads depicting the Obas and Iyobas of Benin. The most well-known artifact is based on Queen Idia, now best known as the FESTAC. Mask after its use in 1977 in the logo of the Nigeria-financed and hosted Second Festival of Black & African Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77).

The first European travelers to reach Benin were Portuguese explorers under João Afonso de Aveiro in about 1485. A strong mercantile relationship developed, with the Edo trading slaves and tropical products such as ivory, pepper and palm oil for European goods such as manillas and guns. In the early 16th century, the Oba sent an ambassador to Lisbon, and the king of Portugal sent Christian missionaries to Benin City. Some residents of Benin City could still speak a pidgin Portuguese in the late 19th century. The first English expedition to Benin was in 1553, and significant trading developed between Europe and Benin based on the export of ivory, palm oil, pepper, and later slaves. Visitors in the 16th and 19th centuries brought back to Europe tales of “Great Benin”, a fabulous city of noble buildings, ruled over by a powerful king. A fanciful engraving of the settlement was made by a Dutch illustrator, from descriptions alone and was shown in Olfert Dapper’s Naukeurige Beschrijvinge der Afrikaensche Gewesten, published in Amsterdam in 1668.[36] The work states the following about the royal palace:

The king’s court is square and located on the right-hand side of the city, as one enters it through the gate of Gotton. It is about the same size as the city of Haarlem and entirely surrounded by a special wall, comparable to the one which encircles the town. It is divided into many magnificent palaces, houses and apartments of the courtiers, and comprises beautiful and long squares with galleries, about as large as the Exchange at Amsterdam. The buildings are of different sizes however, resting on wooden pillars, from top to bottom lined with copper casts, on which pictures of their war exploits and battles are engraved. All of them are being very well maintained. Most of the buildings within this court are covered with palm leaves, instead of with square planks, and every roof is adorned with a small spired tower, on which cast copper birds are standing, being very artfully sculpted and lifelike with their wings spread. Another Dutch traveler, David van Nyendael, visited Benin in 1699 and also wrote an account of the kingdom. Nyendael’s description was published in 1704 as an appendix to Willem Bosman’s Nauwkeurige Beschryving van de Guinese Goud-, tand- en Slave-kust.[37] In his description, Nyendael states the following about the character of the Benin people: The inhabitants of the Benin are in general a kind and polite people, of whom one with kindness might get everything he desires. Whatever might be offered to them out of politeness, will always be doubled in return. However, they want their politeness to be returned with likewise courtesy as well, without the appearance of any disappointment or rudeness, and rightly so. To be sure, trying to take anything from them with force or violence, would be as if one tries to reach out to the Moon and will never be left unreckoned. When it comes to trade, they are very strict and will not suffer the slightest infringement of their customs, not even a iota can be changed. Though, when one is willing to accept these customs, they are very easy-going and will cooperate in every way possible to reach an agreement. Given this characterization of the Benin culture, it might be understood that the Oba did not accept any colonial aspirations. As soon as the Oba began to suspect Britain of larger colonial designs, it ceased communications with their representations until the Benin Expedition of 1896–97, when a British expeditionary force captured, sacked, and burnt Benin City. The rampage continued, ceaselessly over a period of nine long days, as part of a punitive expedition, which brought the kingdom’s imperial era to an end.[38] The military operations relied on a well-trained disciplined force. At the head of the host stood the Oba of Benin. The monarch of the realm served as supreme military commander. Beneath him were subordinate generalissimos, the Ezomo, the Iyase, and others who supervised a Metropolitan Regiment based in the capital, and a Royal Regiment made up of hand-picked warriors that also served as bodyguards. Benin’s queen mother, the Iyoba, also retained her own regiment, the “Queen’s Own”. The Metropolitan and Royal regiments were relatively stable semi-permanent or permanent formations. The Village Regiments provided the bulk of the fighting force and were mobilised as needed, sending contingents of warriors upon the command of the king and his generals. Formations were broken down into sub-units under designated commanders. Foreign observers often commented favorably on Benin’s discipline and organization as “better disciplined than any other Guinea nation”, contrasting them with the slacker troops from the Gold Coast. Until the introduction of guns in the 15th century, traditional weapons like the spear, short sword, and bow held sway. Efforts were made to reorganise a local guild of blacksmiths in the 18th century to manufacture light firearms, but dependence on imports was still heavy. Before the coming of the gun, guilds of blacksmiths were charged with war production, particularly swords and iron spearheads.

Benin’s tactics were well organized, with preliminary plans weighed by the Oba and his sub-commanders. Logistics were organised to support missions from the usual porter forces, water transport via canoe, and requisitioning from localities the army passed through. Movement of troops via canoes was critically important in the lagoons, creeks and rivers of the Niger Delta, a key area of Benin’s domination. Tactics in the field seem to have evolved over time. While the head-on clash was well known, documentation from the 18th century shows greater emphasis on avoiding continuous battle lines, and more effort to encircle an enemy (ifianyako). Fortifications were important in the region and numerous military campaigns fought by Benin’s soldiers revolved around sieges. As noted above, Benin’s military earthworks are the largest of such structures in the world, and Benin’s rivals also built extensively. Barring a successful assault, most sieges were resolved by a strategy of attrition, slowly cutting off and starving out the enemy fortification until it capitulated. On occasion, however, European mercenaries were called on to aid with these sieges. In 1603–04 for example, European cannon helped batter and destroy the gates of a town near present-day Lagos, allowing 10,000 warriors of Benin to enter and conquer it. As payment, the Europeans received items, such as palm oil and bundles of pepper. The example of Benin shows the power of indigenous military systems, but also the role outside influences and new technologies brought to bear. This is a normal pattern among many nations

Benin temporarily declined after 1700 following a civil war, then partially recovered later in that century, only to decline once again in the late 19th century. Benin’s economy was previously thriving in the early to mid-19th century with the development of the trade in palm oil, and the continuation of the trade in textiles, ivory and other resources. To preserve the kingdom’s independence, bit by bit the Oba banned the export of goods from Benin, until the trade was exclusively in palm oil. By the last half of the 19th century Great Britain had come to want a closer relationship with the Kingdom of Benin; for British officials were increasingly interested in controlling trade in the area and in accessing the kingdom’s rubber resources to support their own growing tyre market. Several attempts were made to achieve this end beginning with the official visit of Richard Francis Burton in 1862 when he was consul at Fernando Pó. Following that came attempts to establish a treaty between Benin and the United Kingdom by Hewtt, Blair and Annesley in 1884, 1885 and 1886 respectively. However, these efforts did not yield any results. The kingdom resisted becoming a British protectorate throughout the 1880s, but the British remained persistent. Progress was made finally in 1892 during the visit of Vice-Consul Henry Galway. This mission was the first official visit after Burton’s. Moreover, it would also set in motion the events to come that would lead to Oba Ovonramwen’s fall from power, with the Galway Treaty of 1892

In the late 19th century, the Kingdom of Benin managed to retain its independence and the Oba exercised a monopoly over trade which British merchants in the region found irksome. The territory was coveted by an influential group of investors for its rich natural resources such as palm-oil, rubber and ivory. After British consul Richard Burton visited Benin in 1862 he wrote of Benin’s as a place of “gratuitous barbarity which stinks of death”, a narrative which was widely publicised in Britain and increased support for the territory’s colonization. In spite of this, the kingdom maintained its independence and was not visited by another representative of Britain until 1892 when Henry Gallwey, the British Vice-Consul of the Oil Rivers Protectorate, later the Niger Coast Protectorate, visited Benin City hoping to open up trade and ultimately annex Benin Kingdom and transform it into a British protectorate.[39] Gallwey was able to get Omo n’Oba (Ovonramwen) and his chiefs to sign a treaty which gave Britain legal justification for exerting greater influence over the Empire. While the treaty itself contains text suggesting Ovonramwen actively sought Benin to become a protectorate, this was contrasted by Gallway’s own account, which suggests the Oba was hesitant to sign the treaty. Although some suggest that humanitarian motivations were driving Britain’s actions, letters written between colonial administrators suggest that economic motivations were predominant. The treaty itself does not explicitly mention anything about Benin’s “bloody customs” that Burton had written about, and instead only includes a vague clause about ensuring “the general progress of civilisation”.

A British delegation departed from the Oil Rivers Protectorate in 1897 with the stated aim of negotiating with the Oba of Benin. When the general public in Benin discovered that the delegation’s true intentions was to stage an invasion to depose the Oba, without approval from the Oba, his generals ordered a preemptive attack on the delegation which approaching Benin City, which included eight unknowing British representatives, all but two of whom were killed. A punitive expedition was launched in response, and a 1,200-men strong British expeditionary force, under the command of Sir Harry Rawson, captured, sacked and burnt Benin City. The expeditionary force also looted the palace art. The looted portrait figures, busts, and groups created in iron, carved ivory, and especially in brass, conventionally termed the “Benin Bronzes”, were sold off to defray the cost of the expedition and some were accessioned to the British Museum. Most were sold elsewhere and are now on display in various museums around the world. In March 2021, institutions in Berlin, Germany and Aberdeen, Scotland announced decisions to return Benin Bronzes in their possession to their place of origin.[40]

Soldiers posing with the pillaged artifacts from the Benin Royal Palace stolen by the British between 09th and 18th February 1897. Note the Royal Cheetah made in Ivory

On 13th January 1897, the London ‘Times’ announced news of a “Benin Disaster”. A British delegation, seeking to enter Benin City during an important religious ceremony, exclusively reserved for the Royal Court and rightfully restricted to the credited citizens of Benin, was denied permission to enter the city. However, the foreign British delegation elected to proceed, in spite of the restriction and was then attacked by the military of Benin. This skirmish resulted in the demise of some of its members during the altercation. The details of what actually happened are still far from clear, and have been vigorously disputed, but whatever the real facts, the British, in ostensible revenge for the killing, organised a punitive expedition which raided Benin City, exiled the Oba and created the British protectorate of Southern Nigeria. The booty from the attack on Benin included carved ivory tusks, coral jewelry and hundreds of bronze statues and plaques. Many of these objects were then auctioned off to cover the costs of the expedition, and they were bought by museums across the world.[41]

Recently, the interest in the forgotten Benin Bronzes has been rekindles by the former President of Performing Musicians Employers Association of Nigeria (PMAN) and one of country’s foremost filmmakers, Obafemi Lasode, has said his latest movie, Africa’s Stolen Treasures, is ready to b released in the cinemas.[42] This solo campaigner, for the return of stolen treasures of colonised African countries, said that the movie is a wakeup call to Africans, at home and in the diaspora to be actively involved in return of numerous items of treasure stolen from the continent, by the imperial colonialist, in the past, These rare and precious artworks are in museums and galleries across Europe and America, silently longing for home. Britain and France are the biggest culprits in this shameful plunder of Africa’s cultural heritage, with their museums holding thousands of stolen works of art, which rightfully belong to the people of Africa, as a whole, and especially to their countries of origin of these artifacts. While these cultural valuables from Benin, previously occupied and plundered by Britain and European countries are gradually being returned to their rightful owners, the permanent damage and derating of indigenous peoples in the process has drained the countries of it moral wealth and has successfully portrayed these once highly flourishing civilisations, as derelict nations, in the eyes of western countries, who do not wish to acknowledge the creative and artistic talents originating in and housed amongst the Black peoples of Africa, in a global context.[43]

Many extraordinary theories were put forward, at the time, when Europeans first saw the looted Benin Bronzes. In order to discredit the fine craftmanship of Benin, in creating these artworks, the Europeans declared that the plaques must have come from Ancient Egypt, or perhaps the people of Benin were one of the lost tribes of Israel. The sculptures must have derived from European influence, after all, these were the contemporaries of Michelangelo, Donatello and Cellini. But in fact, research conclusively established that the Benin plaques were entirely West African creations, made without European influence. It is a bewildering fact that the early, broadly harmonious, relationship between Europeans and West Africans established in the 16th century had, by 1900, almost completely disappeared from European memory. Most of Europe had simply forgotten that they had at once admired the court of the Oba of Benin, yet this strange amnesia? According to Obafemi Lasode it is probably because the later relationship was so dominated by the transatlantic slave trade, with all its dehumanising implications.

Later still, there would be the great European scramble for Africa, in which the punitive expedition of 1897 was merely one bloody incident. That raid, and the removal of some of Benin’s great art works, may have spread knowledge of Benin’s culture to the world, but it left a wound in the consciousness of many Nigerians, a wound that is still felt keenly today, as Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian poet and playwright, who in 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature,[44] describes: “When I see a Benin Bronze, I immediately think of the mastery of technology and art – the welding of the two. I think immediately of a cohesive ancient civilisation. It increases a sense of self-esteem, because it makes you understand that African society actually produced some great civilisations, established some great cultures. And today it contributes to one’s sense of the degradation that has overtaken many African societies, to the extent that we forget that we were once a functioning people before the negative incursion of foreign powers. The looted objects are still today politically loaded. The Benin Bronze, like other artefacts, is still very much a part of the politics of contemporary Africa and, of course, Nigeria in particular.”

Olasode said these artefacts do not mean any other thing than aesthetic and monetary value to the looters. However, to Africa, “these pieces carry our history, culture and identity.”[45]

The Bottom Line is that The Benin plaques, these beautiful and disturbing objects, speak as powerfully today as they did when they first arrived in Europe, 0ver a hundred years ago. To many, they are not only supreme sculptures, but a reminder that in the 16th century, Europe and Africa were able to deal with each other on equal terms. In America at the same time, the situation was quite different. There, the terms of engagement between the local inhabitants and the European intruders were profoundly unequal. However, the British colonial aspirations changed the scenario for ever, in the rich and cultured leading to the savage destruction of a once flourishing kingdom in Africa as it did in India, Afghanistan and Burma, with stolen or misappropriated religious and cultural artefacts from colonies, to be housed in colonial museums.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Hercules_Read#:~:text=Sir%20Charles%20Hercules%20Read%2C%20Kt%20FSA%20FRAI%20FBA,1919%20to%201924%2C%20after%20being%20Secretary%20since%201892.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benin_Expedition_of_1897#:~:text=Obinyan%2C%20T.%20U.%20(September%201988).%20%22The%20Annexation%20of%20Benin%22.%20Journal%20of%20Black%20Studies.%20Sage%20.%2019%20(1)%3A%2029%E2%80%9340.%20doi%3A10.1177/002193478801900103.%20JSTOR%C2%A02784423

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode77/

[4] https://www.bing.com/search?q=Oba+ruler&filters=ufn%3a%22Oba+ruler%22+sid%3a%22e94b522e-e083-1abc-0247-8efa52481228%22&FORM=SNAPST

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#CITEREFStrayer2013

[6] Bondarenko, Dmitri; Roese, Peter (1 January 1999). “Benin Prehistory. The Origin and Settling Down of the Edo”. Anthropos: International Review of Anthropology and Linguistics. 94: 542–552.

[7] Connah, Graham (2004). Forgotten Africa: An Introduction to Its Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 125-6. ISBN 978-0415305914.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Ben%20Cahoon.%20%22Nigerian%20Traditional%20States%22.%20Worldstatesmen.org

[9] Patrick Darling (2015). “Conservation Management of the Benin Earthworks of Southern Nigeria: A critical review of past and present action plans”. In Korka, Elena (ed.). The Protection of Archaeological Heritage in Times of Economic Crisis. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 341–352. ISBN 9781443874113.

[10] Ogundiran, Akinwumi (June 2005). “Four Millennia of Cultural History in Nigeria (ca. 2000 B.C.–A.D. 1900): Archaeological Perspectives”. Journal of World Prehistory. 19 (2): 133–168. doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9003-y. S2CID 144422848.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=MacEachern%2C%20Scott.%20%22Two%20thousand%20years%20of%20West%20African%20history%22.%20African%20Archaeology%3A%20A%20Critical%20Introduction.%20Academia.

[12] Connah, Graham (June 1967). “New Light on the Benin City Walls”. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria. 3 (4): 597–599. ISSN 0018-2540. JSTOR 41856902.

[13] Hodgkin, Thomas (1960). Nigerian Perspectives: An Historical Anthology. Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0192154347.

[14] Hodgkin, Thomas (1960). Nigerian Perspectives: An Historical Anthology. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0192154347.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Connah%2C%20Graham%20(June%201967).%20%22New%20Light%20on%20the%20Benin%20City%20Walls%22.%20Journal%20of%20the%20Historical%20Society%20of%20Nigeria.%203%20(4)%3A%20597%E2%80%93599.%20ISSN%C2%A00018%2D2540.%20JSTOR%C2%A041856902.

[16] Connah, Graham (January 1972). “Archaeology of Benin”. The Journal of African History. 13 (1): 33. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000244.

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Connah%2C%20Graham%20(June%201967).%20%22New%20Light%20on%20the%20Benin%20City%20Walls%22.%20Journal%20of%20the%20Historical%20Society%20of%20Nigeria.%203%20(4)%3A%20608.%20ISSN%C2%A00018%2D2540.%20JSTOR%C2%A041856902.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=http%3A//www.beninmoatfoundation.org/clarioncall.html%20Archived%2025%20July%202011%20at%20the%20Wayback%20Machine

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Pearce%2C%20Fred.%20African%20Queen.%20New%20Scientist%2C%2011%20September%201999%2C%20Issue%202203

[20] https://www.wbez.org/stories/ethnomathematician-ron-eglash-indigenous-knowledge-dismantles-white-supremacy/43485dac-eda6-46f6-af58-a2e08cc3d84f

[21] Koutonin, Mawuna (18 March 2016). “Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace”. The Guardian.\

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Oliver%2C%20Roland%20(1977).%20The%20Cambridge%20History%20of%20Africa%2C%20Volume%203%3A%20From%20c.1050%20to%20c.1600.%20Cambridge%20University%20Press.%20p.%C2%A0476.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0521209816.

[23] Ryder, A. F. C. (March 1965). “A Reconsideration of the Ife-Benin Relationship”. The Journal of African History. 6 (1): 25–37. doi:10.1017/s0021853700005314. ISSN 0021-8537.

[24] Millar, Heather (1996). The Kingdom of Benin in West Africa. Benchmark Books. pp. 14. ISBN 978-0761400882.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Zeijl%2C%20Femke%20van.%20%22The%20Oba%20of%20Benin%20Kingdom%3A%20A%20history%20of%20the%20monarchy%22.%20aljazeera.com.

[26] https://wwwt.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pwmn_3/hd_pwmn_3.htm

[27] https://guardian.ng/saturday-magazine/c105-saturday-magazine/emotan-tale-of-ancient-benin-kingdom-on-muson-stage/

[28] https://guardian.ng/sunday-magazine/queen-iden-selfless-intercessor/

[29] https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u152217

[30] Perishable. “Benin Kingdom Loses Prominent Chief, As Obaseki Mourns the Obasogie – TELL”. tell.ng.

[31] rigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study. New York: Cambridge University Press

[32] Graham, James D. (1965). “The Slave Trade, Depopulation and Human Sacrifice in Benin History: The General Approach”. Cahiers d’Études Africaines. 5 (18): 327–30. doi:10.3406/cea.1965.3035. JSTOR 4390897.

[33] Bradbury, R.E. (2017). The Benin Kingdom and the Edo-speaking Peoples of South-western Nigeria. Routledge. pp. 54–8. ISBN 978-1315293837.

[34] Law, Robin (January 1985). “Human Sacrifice in Pre-Colonial West Africa”. African Affairs. 84 (334): 65. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097676. JSTOR 722523.

[35] Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0-521-82245-9. OCLC 50291226

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Dapper%2C%20Olfert%20(1668).%20Naukeurige%20Beschrijvinge%20der%20Afrikaensche%20Gewesten.%20Amsterdam%3A%20Jacob%20van%20Meurs.%20p.%C2%A0495

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Bosman%2C%20Willem%20(1704).%20%22Beschryving%20van%20Rio%20Formosa%2C%20Anders%20gesegt%20de%20Benin.%22.%20Nauwkeurige%20Beschryving%20van%20de%20Guinese%20Goud%2Dtand%2Den%20Slave%2Dkust.%20Utrecht%3A%20Anthony%20Schouten.%20pp.%C2%A0212%E2%80%93257.

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#:~:text=Bosman%2C%20Willem%20(1704).%20Nauwkeurige%20Beschryving%20van%20de%20Guinese%20Goud%2Dtand%2Den%20Slave%2Dkust.%20Utrecht%3A%20Anthony%20Schouten.%20pp.%C2%A0222%20f.

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Benin#CITEREFIgbafe1970

[40] “The kingdom of Benin was obliterated by the British, who still have the evidence on display”. abc.net.au. 29 November 2020.

[41] https://sites.google.com/site/100objectsbritishmuseum/home/benin-plaque-the-oba-with-europeans

[42] https://guardian.ng/art/olasode-in-search-of-africas-stolen-treasure/

[43] https://guardian.ng/art/olasode-in-search-of-africas-stolen-treasure/#:~:text=According%20to%20him,works%20of%20art.

[44] https://www.biography.com/writer/wole-soyinka

[45] https://guardian.ng/art/olasode-in-search-of-africas-stolen-treasure/#:~:text=Olasode%20said%20these%20artefacts%20do%20not%20mean%20any%20other%20thing%20than%20aesthetic%20and%20monetary%20value%20to%20the%20looters.%20However%2C%20to%20Africa%2C%20%E2%80%9Cthese%20pieces%20carry%20our%20history%2C%20culture%20and%20identity.%E2%80%9D

[46] https://www.bing.com/search?q=picture+of+Throne+Chetahs+in+Ivory+in+Benin&cvid=e84e89d15681458d91f551a0a56f078d&aqs=edge..69i57.42469j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: British Colonialism, British empire, Colonization, Corruption, Europe, Geopolitics, Hinduism, History, India, Politics, Religion

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 14 Mar 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Imperial, Colonial Thieves: The Annihilation of the Kingdom of Benin and Pillaging of the Royal Palace by British Soldiers (Part 3), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.