The Martyrs of Apartheid in pre-1994 South Africa: Ahmed Timol (Part 1)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 11 Jul 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

(Please note that certain images in this publication may be disturbing to some readers. Parental guidance is advised.)

‘The Murder of Innocence by Brutal, Racist, White Security Forces’[1]

In present day, post liberation, South Africa, if the name of Ahmed Timol is mentioned, 99% of the born free South Africans after 1994, have absolutely no idea as to who he is or was, nor do they know anything about him, let alone the fact that he was a political activist, a person of Indian origins, against the oppressive apartheid regime of the White minority in South Africa. Yet even fewer citizenry know that Timol was murdered by the White, dreaded Security Branch officials, while in police detention, without trial for crimes against apartheid. This was an official, legislative tome, to oppress and ensure the legalized discrimination of people of colour in South Africa, since the arrival of the white man in 1652, Jan van Riebeeck[2], as part of colonial expansionism of European invaders of Indigenous African land.

Furthermore, it is also interesting to note that on some website search engines, when “Timol” is typed, the response is “Thymol” which then proceeds to lists the details of this chemical compound. Noting this deficiency, this paper highlights, in the first publication in this series, on the martyrs of apartheid and what happened to Mr Ahmed Yusuf Timol, as a young political activist, who died while in police detention in the notorious John Vorster Square, located on No.1 Commissioner Street in downtown Johannesburg, in the former Transvaal province of South Africa, now called Gauteng. This horror of apartheid regime, used to torture and kill political detainees often with trial, terminated as a many as eight prisoners in the building during the height of apartheid oppression of activists not only of colour, but also a White dissident against the regime, Dr. Neil Hudson Aggett.[3] Dr Aggett was a South African labour activist, medical doctor, organiser of the Transvaal Brach of the African Food and Canning Workers’ Union and the first White South African to die in police detention, after being detained for 70 days, on 05th February 1982.

Jane Starfield mourns dead Security Police detainee Dr Neil Hudson Aggett outside John Vorster Square.

(Photo: Gallo Images / Sunday Times)

This anti-apartheid union organiser, Dr Neil Aggett who was 28 years old was reportedly “found hanged” in Cell 209 by police in the notorious John Vorster Square after Security Police torture and 62 hours of interrogation.[4] He was a white martyr of apartheid.

It is therefore relevant to review the brief history of this infamous security police detention centre as an essential symbol of death of anti-apartheid activists in the South African liberation struggle. While this monument of oppression has its history dating back to 1912, John Vorster Square was officially opened on the 23rd August 1968 by John Vorster, then the prime minister of the Republic of South Africa. It was a 10 storey, blue-coloured cement building.[5] The ninth and tenth floors were occupied by the Security Branch of the South African Police, while the detainees cells were on the lower floors of the building.[6] In September 1997, post liberation, under the government of the African National Congress[7], John Vorster Square was renamed Johannesburg Central Police Station, and the decorative, memorial bust of Vorster was removed. It now houses the South African Police Service.

During the apartheid era, the John Vorster Square station was a notorious site of interrogation, torture and abuse by the South African Security Police of anti-apartheid activists,[8] many of whom, after 1982, were held under the Internal Security Act[9]. John Vorster Square was also used as a detention centre mostly for political activists; those sent into “detention” were not allowed to have any contact with family members, lawyers or any outside help; they were cut off from the rest of the world, completely. Detention could last for a few hours to a few months, depending on the police, and the suspected anti-apartheid misdemeanour. No opportunity was afforded to the detainees for any legal recourse and for a due process to be followed, prior to their indefinite detention.

Of the 73 known deaths of political activists in police custody in South Africa between 1963 and 1990, eight (11%) were at John Vorster Square.[10],[11] Government and police officials claimed that the large number of deaths were due to politically motivated suicides, in the words of one police official as part of a “communist plot.”[12] Even when the reported cause of death was corroborated by an official inquest, civil society largely mistrusted the police’s accounts of the deaths. At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, police officers and activists testified extensively about the use of torture in detention[13] and three of the inquests into deaths at John Vorster have since been reopened.

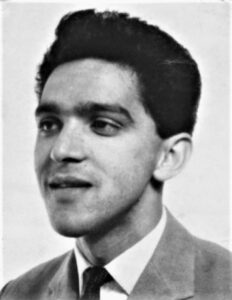

Five of the deaths at John Vorster were recorded as suicides, on which the Commission concluded the following: – “Given the extensive evidence of physical, as well as psychological torture, suicides under conditions of detention should be regarded as induced suicide for which the security forces and the former government are accountable.” [14] Such were the highly dubious circumstances of the untimely demise of Mr Ahmed Yusuf Timol. He was the first detainee to die while in police detention at John Vorster Square. He was a 30 year old teacher and political activist, as well as an underground member of the South African Communist Party and Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress. On 27 October 1971, Ahmed Timol plunged to his death from the infamous 10th floor, five days after his arrest. The police claimed that he had committed suicide and an official inquest into his death in 1972 backed up this claim, despite evidence that he had been subjected to severe torture before his death. A subsequent inquest into Timol’s death in 2017 overturned the ruling of the 1971 inquest, and found that Timol had indeed been murdered by the security police.[15] He was therefore the first martyr of apartheid at Jon Vorster Square.

First Apartheid Martyr to die in police detention at John Vorster Square in Johannesburg, on 27 October 1971

Timol was born on 03rd November 1941 in Breyten, Transvaal, into a large Muslim family.[16] Timol was one of six children, with two sisters, Zubeida and Ayesha, and three brothers, Ismail, Mohammed and Haroon. His father, a shopkeeper, came to South Africa in 1918, at the age of 12, from the Kholvad district of Surat in western India.[17] Timol joined a semi-clandestine Roodepoort Youth Study Group while still a student at Johannesburg Indian High School[18] and became friends at school with the brothers Aziz Pahad and Essop Pahad, both of whom would become prominent anti-apartheid activists.[19]

In 1956, at the age of 15, Timol made a speech in class about the nationalisation of the Suez Canal by President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt. His teacher warned him that the speech was political. He completed his matriculation in 1959 at the JIHS. Here he met Aziz and Essop Pahad, sons of Goolam Pahad, his father’s close friend, and a member of the TIC. The Pahad brothers became his closest friends.

At a young age, Timol had his first brush with the law. He and his friend Yusuf JoJo Saloojee were travelling by train from Roodepoort to Johannesburg, when a student claimed that he had a leaked an exam paper. Timol and Saloojee asked for the paper to be burnt as it would lead to them being in trouble if they were caught with it. The boys burnt the paper and while it was burning a White conductor entered the coach and upon seeing the burning paper, locked the coach. At the next station the train was met by a group of police, the Security Branch included. The pair managed to escape but other boys gave their names to the police. Later, the police visited the boys’ homes. His mother urged her son to provide the names of the boys who were really the owners of the leaked exam paper, but Timol refused to cooperate with the police.[20]

On 09th September 1964, Suliman ‘Babla’ Saloojee, a Transvaal Indian Congress [21]member, was killed in police detention. Students from Lenasia and Roodepoort, went on a peaceful demonstration at the Fordsburg Police Station. Timol and JoJo Saloojee discussed this incident and concluded that a cadre would never kill himself. The police said that Babla had committed suicide. After Babla’s death, the two boys distributed leaflets issued by the Transvaal Indian Youth Congress (TIYC) and narrowly escaped being caught by the police whilst doing so.

Since there were no sporting facilities available to Indians in Roodepoort, the Roodepoort Muslim Club (RMC) was the only option open to the community. Timol and Saloojee initially refused to join because the club was sectarian as it admitted Muslims only. The two discussed this and Timol suggested that they join in order to politicise the organisation.

On one occasion, hosted by the RMC, Timol directed his outburst at the rich leaders of the club who excluded the poorer sections of the community. Consequently, Timol and Saloojee were hauled before the Club’s Disciplinary Committee but were cautioned. At another of RMC’s annual meeting, he raised the issue of membership being restricted to Muslims only and again Saloojee and Timol were asked to leave but were subsequently allowed to return.

Ahmed Bhabha was responsible for recruiting Mohamed Bhabha, Yusuf Jo Jo Saloojee and Timol, then a high school student, into the Roodepoort Youth Study Group (RYSG), a small political awareness group. The study group was in some ways linked to the TIYC. The objective of the Group was to study the political situation South Africa and the world. When Chief Albert Luthuli visited Roodepoort to address a meeting, members of the RYSG and Timol formed a guard of honour to welcome him. After his speech, the Chief was issued with a banning order.

The meetings of the RYSG were not publicised. Thus, the group was able to invite banned persons such as Ahmed Kathrada, renowned writer Ezekiel (Es’kia) Mphalele and other personalities. Mphalele had a profound impact on Timol. The Group also read and discussed Father Trevor Huddleston’s, Naught for your Comfort. Father Huddleston was an Anglican priest based in Sophiatown, Johannesburg. These meetings would go on late into the night by which time most of the people would have left. The evening’s discussions would end with the group singing political songs. For those times, this was quite a radical act of defiance.

After completing high school, in 1959, his father required another operation for his failing eyesight. This inevitably put a strain on the family’s income. Timol’s sister, Aysha had to leave school. In spite of a matriculation exemption, Timol was forced to take up employment as a clerk at a bookkeeper’s office in Johannesburg, in 1960, to augment the family income.[22]

After working as a clerk for some years, Timol received a scholarship from the Kholvad Madressa in Surat to pursue a teaching course at the Johannesburg Training Institute for Indian Teachers, the only institution of higher education for Indians in the Transvaal at the time. He was Vice-Chairman of the Student Representative Council from 1962 to 1963, and the SRC became an affiliate of the National Union of South African Students in 1963.

After teaching for some time at a school in Roodepoort, in 1966 Timol left South Africa for Mecca for the Hajj. In Saudi Arabia, he met and was inspired by Yusuf Dadoo, leader of the Transvaal Indian Congress and later the Chairman of the South African Communist Party (SACP), and Moulvi Cachalia, an African National Congress (ANC) stalwart.[23] In April 1967, Timol went London, where he lived with the Pahads.[24] He took up a teaching post at the Immigration School at Slough, which provided him with funds, became an active member of the National Union of Teachers and met Ruth Longoni, who worked for the Labour Monthly, a journal run by Rajani Palme Dutt of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The two came close to marrying, but Timol left for Moscow in the Soviet Union in 1969, as he had been selected to study at the International Lenin School. He was trained in Marxist-Leninist ideology, along with three fellow South Africans, one of them Thabo Mbeki, then a communist, later South African state president.[25] After completing his training, Timol returned to London and received additional training for four weeks from Jack Hodgson, an SACP member in exile.

In February 1970, Timol returned to Roodeport in South Africa and resumed teaching. He was active in the SACP and in Umkhonto we Sizwe [26](MK), the paramilitary wing of the ANC, though both had been banned in 1960. His political work included recruitment for the ANC, MK and SACP, producing and distributing pamphlets, and procuring equipment for underground, anti-apartheid structures.[27],[28]

In October 1971, aged 29, Timol was arrested at a roadblock. According to the police officers they found banned ANC and SACP literature, as well as copies of secret communication correspondence, in the boot of the car he was travelling in.[29] He was detained under the Terrorism Act of 1967 with Amina Desai and two others, all of whom later said that they had been severely tortured in custody.[30] He died on 27th October, five days after his arrest, from injuries sustained when he reportedly fell from the tenth floor of John Vorster Square police station in Johannesburg. He was the first political detainee to die in Security Branch custody at John Vorster Square. The police claimed that he had jumped from a window, which his family disputed in the press.[31]

In the police version of Timol’s detention, they claimed that he admitted having contact with the SACP in London. The police further claimed that on 27 October 1971, while Timol was alone with a policeman, Sergeant J Rodrigues at John Vorster Square, he rushed to a window, opened it and dived out, landing on Commissioner Street. There was no mention at all of assault or torture meted out on Timol. Timol’s brother, Mohammed, was not allowed out of detention to attend his brother’s funeral. On 29 October, two days after his death, contrary to Islamic custom, whereby the deceased must be interred shortly after the demise, Timol’s family was given his body for burial. During the washing of the body for burial according to Muslim rites, it was observed that his neck was broken and that his fingernails were taken out and that his elbow was burnt. An undertaker, Mohammed Khan, who saw Timol’s body in the mortuary, observed that his eye was out of its socket, his body was covered in blue marks and that he had burn marks all over his body.[32]

Several thousand people attended his funeral in Roodepoort. Roodepoort came to a standstill. All Indian businesses closed as a mark of respect. There was a heavy police presence at the funeral. They even took photographs as Timol’s body was lowered into the grave. Even after Timol’s funeral, the security police harassment did not stop. Timol’s sister, Ayesha, would be followed by the Security Police as she walked from home to the mosque. After the funeral, the police questioned everyone who was associated with him, further traumatising the community. They would visit the Timol family flat and even search through the dustbins.

His death sparked nationwide shock, anger and demands for an inquiry. Support for such an inquiry came from a broad spectrum of the South African population that included the United Party (UP), various churches, the black South African Students Association, the Coloured Labour Party, and the Indian Congresses. In Durban, a packed meeting attended by people of all races called for a national day of mourning, which was observed on 10th November 1971.

An official inquest on 22nd June 1972 ruled that his death had been a suicide. The presiding magistrate suggested that Timol had killed himself after disclosing sensitive information during interrogation, because he feared imprisonment, and because the SACP had instructed its members to kill themselves before betraying the party.[33] The inquest magistrate found that no one was to blame for Ahmed Timol’s death. Effectively, the magistrate ruled that Timol had committed suicide and all details of his brutal torture were excluded. Thus the apartheid state was absolved of all responsibility for Timol’s death in detention.[34]

Timol’s family, including his aged mother, Mrs Hawa Timol[35] who delivered a graphic account of the injuries, and others testified about his death at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), and the TRC ultimately assigned responsibility for Timol’s death to several policemen. It also found that “the inquest magistrate’s failure to hold the police responsible for Ahmed Timol’s death contributed to a culture of impunity that led to further gross human rights violations.”[36]

The inquest was reopened in 2017 at the request of Timol’s family. George Bizos was part of the team representing Timol’s family, as he had been in the original 1972 inquest.[37] In October 2017, the second inquest found that Timol had been pushed out the window or off the roof by members of the Security Branch. The inquest also heard evidence that Timol had been tortured during his detention, including from Salim Essop, who had been detained and tortured alongside Timol but whose testimony had been excluded from the original inquest.[38] The presiding Judge said that the officers holding Timol in custody were collectively responsible for his death, and that there was a prima facie case of murder under dolus eventualis against the two officers who had interrogated Timol that day, both of whom had died years earlier.[39] One surviving officer, Joao Rodrigues, died in September 2021 while facing a murder charge for Timol’s death.[40] It is also important to note that in Islamic religion, the prescribed tenets, would abhor suicide, which is totally prohibited[41], even under the must trying circumstances, and Timol being a Muslim, would certainly not have subjected himself to self-termination, while in security branch, police custody.[42]

Ahmed Timol, as a Martyr of Apartheid, left a profound, foundational legacy upon his death and more especially following the 2017 inquest, which categorically concluded that the young man was murdered by the Security Branch Police, while in detention. On 29 March 1999, President Nelson Mandela attended a ceremony at which Azaadville Second School in Krugersdorp was renamed after Timol.[43] President Jacob Zuma posthumously awarded him the Order of Luthuli (Silver) in 2009,”for his excellent contribution and selfless sacrifice in the struggle against apartheid.”[44],[45]

The Bottom Line is that the apartheid state apparatus was brutale and secretive, with a profound sense of paranoia developed specifically for the preservation of white dominance which even proceeded to murder of innocent civilians, in order to ensure the safety of the white minority in Southern Africa at the time. Remember South Africa was also supporting Rhodesia, as well as Angola at the time to uphold white minority regimes, which were oppressive against the indigenous population of their occupied lands. Just as in present day Israel, where discrimination against Palestine and targeted killings of journalist as in the case of American-Palestinian journalist, Ms Shireen Abu Akleh on 10th May 2022, by the Israeli Defence Force[46], as now confirmed, the South African security branch was operating in a frame of mind analogous to the Israeli Defence Force, mentality. The irony is that presently, while history is repeating itself in Palestine, the entire world including United States is condoning such atrocities’ as practiced by Israel, fully supported by the Biden administration, so that the killings in Palestine can proceed with impunity, almost on a weekly basis, where young lives are ended by Israeli bullets.

Ahmed Timol in Literature[47]

References:

[1] Personal quote by author June 2022

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_van_Riebeeck

[3] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/dr-neil-hudson-aggett#:~:text=Neil%20Hudson%20Aggett%20was%20born%20in%20Nanyuki%2C%20Kenya,%281964-1970%29%20where%20he%20won%20numerous%20awards%20and%20certificates.

[4] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-01-24-when-they-killed-neil-aggett/

[5] http://www.saha.org.za/news/2010/August/remembering_a_darker_time_when_john_vorster_square_was_opened.htm

[6] http://www.newtown.co.za/heritage/surrounds

[7] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=545df95528bd2fc0479ac9825b55fe8186dea247829357dbb0eb1c36b3465826JmltdHM9MTY1NzM0NjAwMCZpZ3VpZD1jMTc5NTgyMy01MzVkLTQ3OGQtYmIyMS1jNWJhMzFkMDA1ZjMmaW5zaWQ9NTQyNg&ptn=3&fclid=6f476b29-ff4b-11ec-937b-944a0384c16f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQWZyaWNhbl9OYXRpb25hbF9Db25ncmVzcyM6fjp0ZXh0PVRoZSUyMEFmcmljYW4lMjBOYXRpb25hbCUyMENvbmdyZXNzJTIwJTI4JTIwQU5DJTI5JTIwaXMlMjBhLHdpdGglMjBhJTIwcmVkdWNlZCUyMG1ham9yaXR5JTIwZXZlcnklMjB0aW1lJTIwc2luY2UlMjAyMDA0Lg&ntb=1

[8] https://web.archive.org/web/20130208042321/http://heritage.thetimes.co.za/memorials/GP/DeathInDetention/

[9] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=cdff00cbbd7865370942b6d15d2339ec9c76b8f7c36cbac7370ed94e276113a5JmltdHM9MTY1NzM0NjM1NiZpZ3VpZD1mNjM2NDlmNy01NmUzLTQ3MDMtYmNiNy00YzhhMmM2YThmMWImaW5zaWQ9NTM1NQ&ptn=3&fclid=43690051-ff4c-11ec-92de-305448237cda&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvU3VwcHJlc3Npb25fb2ZfQ29tbXVuaXNtX0FjdCxfMTk1MCM6fjp0ZXh0PVRoZSUyMFN1cHByZXNzaW9uJTIwb2YlMjBDb21tdW5pc20lMjBBY3QlMkMlMjAxOTUwJTIwJTI4QWN0JTIwTm8uLHRvJTIwYSUyMHVuaXF1ZWx5JTIwYnJvYWQlMjBkZWZpbml0aW9uJTIwb2YlMjB0aGUlMjB0ZXJtLg&ntb=1

[10] https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/detention-without-trial-in-john-vorster-square/gQ-1o9MM

[11] http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/list-deaths-detention

[12] Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (PDF). Vol. 2. Cape Town: The Commission. 1998.

[13] https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/finalreport/Volume%202.pdf

[14] Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (PDF). Vol. 2. Cape Town: The Commission. 1998.

[15] Nicolson, Greg (2017-10-12). “Timol Inquest: He was murdered but culprits are dead, court rules”. Daily Maverick.

[16] Cajee, Imtiaz (2005). Timol: A Quest for Justice. STE. ISBN 978-1-919855-40-0.

[17] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol

[18] https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/opinion/timol-a-proponent-of-equal-education-1936088

[19] Gee, Frank (18 June 2021). Justice for All. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 978-1-64804-943-9.

[20] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol

[21] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=4a94538d4c3dd5a855a18fed4cf1b167f3e750e0fffad268f33011791e0d40f1JmltdHM9MTY1NzM1MTYwMyZpZ3VpZD1iZTU5MTgzNC1iZWRmLTRkZjgtOTc1NS05YWYzYTk3M2Q1YzAmaW5zaWQ9NTE0OA&ptn=3&fclid=7ae1b4cc-ff58-11ec-a637-206f6ec7fed8&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuc2FoaXN0b3J5Lm9yZy56YS9hcnRpY2xlL3RyYW5zdmFhbC1pbmRpYW4tY29uZ3Jlc3MtdGlj&ntb=1

[22] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol#:~:text=In%201956%2C%20at,from%20the%20Kholwad

[23] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol

[24] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmed_Timol#:~:text=Gevisser%2C%20Mark%20(2009).%20A%20legacy%20of%20liberation%20Thabo%20Mbeki%20and%20the%20future%20of%20the%20South%20African%20dream%20(1st%C2%A0ed.).%20New%20York%3A%20Palgrave%20Macmillan.%20p.%C2%A01.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0230620209.

[26] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=1ae78ca95dd0743cc23db8b680333fe658d9705bc37e56ad344e063b4e9d869aJmltdHM9MTY1NzM0OTA0MiZpZ3VpZD1kZjI4ZjBhYi00MDdiLTQ3ZmYtYWNhYi03YzFkODQ1MTZkZjgmaW5zaWQ9NTE1Mg&ptn=3&fclid=84f1cd21-ff52-11ec-9543-ba4a5d7d8e45&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuc2FoaXN0b3J5Lm9yZy56YS9hcnRpY2xlL3Vta2hvbnRvLXdlc2l6d2UtbWs&ntb=1

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmed_Timol#:~:text=South%20African%20Democracy%20Education%20Trust%20(2006).%20The%20road%20to%20democracy%20in%20South%20Africa%20(1st%C2%A0ed.).%20Pretoria%3A%20Unisa%20Press.%20p.%C2%A0440.%20ISBN%C2%A01868884066.

[28] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol

[29] http://www.historicalpapers.wits.ac.za/?inventory_enhanced/U/Collections&c=259936/R/AK3388-D9

[30] https://sabctrc.saha.org.za/reports/volume3/chapter6/subsection8.htm

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmed_Timol#:~:text=Crouse%2C%20Gabriel%3B%20Myburgh%2C%20James%20(23%20October%202017).%20%22Salim%20Essop%27s%20ordeal%20(II)%22.%20Politicsweb.

[32] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol#:~:text=In%20the%20police,through%20the%20dustbins.

[33] https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/hrvtrans/methodis/timol.htm

[34] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol#:~:text=On%2022%20June,death%20in%20detention.

[35] https://youtu.be/cI9qBaHkZSo

[36] https://sabctrc.saha.org.za/reports/volume3/chapter6/subsection8.htm

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmed_Timol#:~:text=Mabena%2C%20Sipho%20(12%20October%202017).%20%22Timol%20judgment%3A%20Bizo%27s%20tears%20of%20closure%22.%20Sunday%20Times.

[38] Myburgh, James (17 October 2017). “The Ahmed Timol case (I)”. Politicsweb.

[39] Nicolson, Greg (12 October 2017). “Timol Inquest: He was murdered but culprits are dead, court rules”. Daily Maverick.

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmed_Timol#:~:text=Mabuza%2C%20Ernet%20(7%20September%202021).%20%22Ahmed%20Timol%20murder%20accused%20Joao%20Rodrigues%20dies%22.%20Sunday%20Times.

[41] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=b3b4eed6175e3e1dc32b2c05bf651b46681d447e23141ba10bdca7e3d0c30a75JmltdHM9MTY1NzM1MTA1MCZpZ3VpZD1mOGU1NGY4ZC03MDZjLTRhNWQtYWFjZi1iZGZkY2Y3MmM1MTAmaW5zaWQ9NTE1MA&ptn=3&fclid=31c45581-ff57-11ec-ac7a-073b0b4e1660&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuaXNsYW1yZWxpZ2lvbi5jb20vYXJ0aWNsZXMvMTAzNzAvZGVzcGFpci1hbmQtc3VpY2lkZS1pbi1pc2xhbS8&ntb=1

[42] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=ad95d26711b951ff92ae0a8dac39147979b0d0e2ab0bfe1db696b447f173a74aJmltdHM9MTY1NzM1MTA1MCZpZ3VpZD1mOGU1NGY4ZC03MDZjLTRhNWQtYWFjZi1iZGZkY2Y3MmM1MTAmaW5zaWQ9NTE3NQ&ptn=3&fclid=31c464af-ff57-11ec-95c8-3dadf7d0f89f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9xdXJhbmZvcmtpZHMuY29tL3N1aWNpZGUtZm9yYmlkZGVuLWlzbGFtLw&ntb=1

[43] https://mg.co.za/article/1999-03-29-school-named-after-ahmed-timol/

[44] Saeed, Abdullah (17 December 2009). “Letter: Honouring a struggle hero”. Witness. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014.

[45] “Presidency unveils National Orders recipients”. South African Government. 2 December 2009.

[46] https://www.transcend.org/tms/2022/05/the-global-killing-fields-of-journalists-the-death-of-shireen-abu-akleh-part-1/

[47] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/ahmed-timol#:~:text=Cajee%2C%20I.(2005,ahmedtimol.co.za

______________________________________________

READ: PART 2 – PART 3 – PART 4

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Activism, Africa, Apartheid, Dissent, History, Nelson Mandela, Racism, South Africa, Torture, White Supremacy

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 11 Jul 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Martyrs of Apartheid in pre-1994 South Africa: Ahmed Timol (Part 1), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.