“Peace in a Cup of Tea” (Part 1): The Beginning

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 10 Oct 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Life Is Like a Cup of Tea – It Is All in How You Make It”[1]

The Beginning of Tea: A Team of Women Tea Labouers in Assam, India Led by a Male, with a bicycle. Photo Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

8 Oct 2022 – This series of publications highlight the history of tea and how the humble leaf, grown in the ancient, global tea plantations, today, has taken the centre stage in the meetings of international diplomacy, briefing of literally, earth shattering decisions, as well as peace negotiations of global powers and the United Nations, in the pursuit of its eternal mandate of maintenance and sustenance of universal peace in the troubled, political hot spots, throughout the world. Often, the cup of tea comes to the rescue of Mother Earth, at the brink of extinction, resulting from the pressing of a BUTTON, either “BIG OR SMALL”, of the destructive nuclear armaments, of mass destruction of humanity. This paper begins at the point of the production of tea in Colonial Assam and West Bengal in India, of old. India is the world’s largest consumer and producer of black tea and has been at the forefront of the global tea industry since the 19th century. This could not have happened without institutions playing a pioneering role in the creation, nurturing and growth of India’s tea industry. The industry has grown into a four-billion-dollar mega-industry and the institutional factors that helped shape it, especially in the Eastern and Southern regions of India.[2]

The first week of October, annually, is an important slot in the calendar of the Nobel Prize, during which the Nobel Prize Committee announces the winners of the Nobel Prizes in the various categories, During this time, most readers, sit down with a cup of hot tea, as is the tradition, glued to their digital, television screens, eagerly watching the news to see how the awarding of the 2022 Nobel Prizes unfold. While these humanoids were sipping their teas, selected from the over 3000 and ever-increasing varieties, best enjoyed in fine, bone china teacups, it became evidently clear and most listeners realized that the entire decision of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee was overarched by the political scenarios of the current and ongoing war in Ukraine. The author has noted that there are some glaring irregularities in the selection process of the laureates by the Nobel Awards Committee. It is interesting to note that the nomination deadline was 31st January 2022 at 12 midnight CET, while the Ukraine war commenced in February. The question which begs asking, is how can a Ukrainian person be awarded a peace prize for documenting war crimes in Ukraine, after the closing date for submissions of nominations, noting that the Russian invasion of Ukraine only commenced on 24th February 2022.

This is clearly a politicised decision, with the Nobel Committee jumping onto the bandwagon of the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the proxy war conducted by the Western allies, has even affected the hallowed functioning of the Nobel Committee in Oslo as the Peace Prizes were announced on global networks. All this intrigue calls for another cup of traditionally brewed cup of tea, prepared in most traditional homes, on the stove in an aluminum pot and served with boiled, hot milk after the tea leaves are strained. The tea is presented to the accompaniment of a traditional, little homemade biscuit. This biscuit is then dipped in the tea and relished by the older individuals in any particular family, which has held onto age old traditions, passed down by generations of an accepted “code of conduct, when it comes to drinking tea. . Needless to mention that younger humanoids, in the present culture of post-modernism, enjoy iced tea, from a soft drink can, as marketed by various soft drink companies, in the 21st century. It is therefore necessary to review the history of tea, as well as the suffering and exploitation of the very labourers, mainly women in India, in general, but concentrating on work of the tea plantation women of Assam.

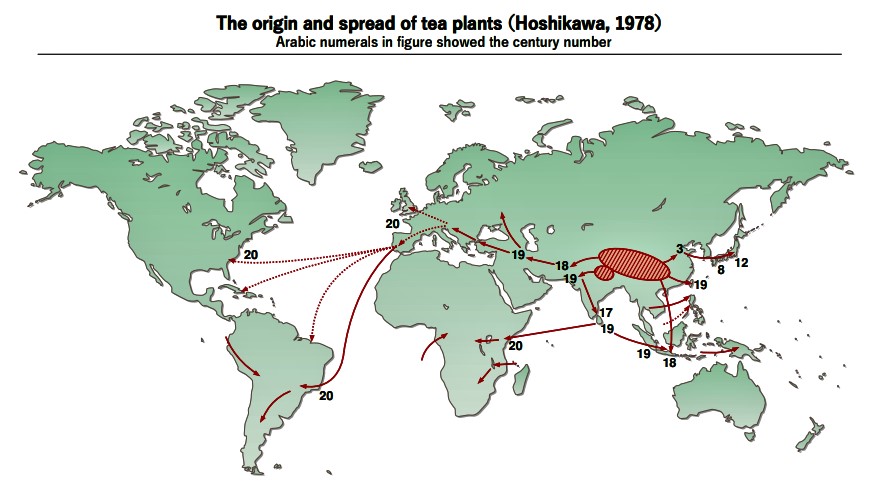

The history of tea spreads across multiple cultures over the span of thousands of years. With the tea plant Camellia sinensis native to East Asia and probably originating in the borderlands of southwestern China and northern Burma.[5],[6] one of the earliest tea drinking is dated back to China’s Shang dynasty, in which tea was consumed as a medicinal drink.[7] An early credible record of tea drinking dates to the 3rd century AD, in a medical text written by Chinese physician Hua Tuo.[8] It first became known to the western world through Portuguese priests and merchants in China during the early 16th century.[9] Drinking tea became popular in Britain during the 17th century. The British introduced commercial tea production to British India, in order to compete with the Chinese monopoly on tea.[10]

In one popular Chinese legend, Emperor Shennong was drinking a bowl of plain boiled water because of a decree that his subjects must boil water before drinking it.[11] This happened around 2737 BC, when a few leaves were blown from a nearby tree into his water, changing the color and taste. The emperor took a sip of the brew and was pleasantly surprised by its flavor and restorative properties. A variant of the legend tells that the emperor tested the medical properties of various herbs on himself, some of them poisonous, and found tea to work as an antidote.[12] Shennong is also mentioned in Lu Yu’s famous early work on the subject, The Classic of Tea.[13]

A similar Chinese legend states that the God of Agriculture would chew the leaves, stems, and roots of various plants to discover medicinal herbs. If he consumed a poisonous plant, he would chew tea leaves to counteract the poison. Another legend dates back to the Tang dynasty. In the legend, Bodhidharma, the founder of Chan Buddhism, accidentally fell asleep after meditating in front of a wall for nine years. He woke up in such disgust at his weakness that he cut off his eyelids. They fell to the ground and took root, growing into tea bushes.[14] Another version of the story has Gautama Buddha in place of Bodhidharma.[15]

The Chinese have consumed tea for over 7000 years. The earliest physical evidence known to date, found in 2016, comes from the mausoleum of Emperor Jing of Han in Xi’an, indicating that tea was drunk by Han dynasty emperors as early as the 2nd century BC.[16] The samples were identified as tea from the genus Camellia particularly via mass spectrometry,[17] and written records suggest that it may have been drunk earlier. People of the Han dynasty used tea as medicine, although the first use of tea as a stimulant is unknown. China is considered to have the earliest records of tea consumption,[18] with possible records dating back to the 10th century BC.[19] Note however that the current word for tea in Chinese only came into use in the 8th century AD, there are therefore uncertainties as to whether the older words used are the same as tea.

The word tu appears in Shijing and other ancient texts to signify a kind of “bitter vegetable”, and it is possible that it referred to several different plants, such as sow thistle, chicory, or smartweed, including tea.[20] In the Chronicles of Huayang, it was recorded that the Ba people in Sichuan presented tu to the Zhou king. The state of Ba and its neighbour Shu were later conquered by the Qin, and according to the 17th century scholar Gu Yanwu who wrote in Ri Zhi Lu: “It was after the Qin had taken Shu that they learned how to drink tea.”[21]

The first known reference to boiling tea came from the Han dynasty work “The Contract for a Youth” written by Wang Bao where, among the tasks listed to be undertaken by the youth, “he shall boil tea and fill the utensils” and “he shall buy tea at Wuyang”.[22] The first record of cultivation of tea also dated it to this period, the Ganlu era of Emperor Xuan of Han, when tea was cultivated on Meng Mountain, near Chengdu. From the Tang to the Qing dynasties, the first 360 leaves of tea grown here were picked each spring and presented to the emperor. Even today its green and yellow teas, such as the Mengding Ganlu tea, are still sought after.[23] An early credible record of tea drinking dates to 220 AD, in a medical text Shi Lun by Hua Tuo, who stated, “to drink bitter t’u constantly makes one think better.”[24] Another possible early reference to tea is found in a letter written by the Qin dynasty general Liu Kun.[25] However, before the mid-8th century Tang dynasty, tea-drinking was primarily a southern Chinese practice.[26] It became widely popular during the Tang dynasty, when it was spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

Laozi, the classical Chinese philosopher, was said to describe tea as “the froth of the liquid jade” and named it an indispensable ingredient to the elixir of life.[27] Legend has it that master Lao was saddened by society’s moral decay, and sensing that the end of the dynasty was near, he journeyed westward to the unsettled territories, never to be seen again. While passing along the nation’s border, he encountered and was offered tea by a customs inspector named Yin Hsi. Yin Hsi encouraged him to compile his teachings into a single book so that future generations might benefit from his wisdom. This became known as the Dao De Jing, a collection of Laozi’s sayings.[28] Tang dynasty writer Lu Yu’s The Classic of Tea is an early work on the subject. According to Cha Jing, tea drinking was widespread. The book describes how tea plants were grown, the leaves processed, and tea prepared as a beverage. It also describes how tea was evaluated. The book also discusses where the best tea leaves were produced. Teas produced in this period were mainly tea bricks which were often used as currency, especially further from the center of the empire where coins lost their value. In this period, tea leaves were steamed, then pounded and shaped into cake or brick forms.[29]

During the Song dynasty, production and preparation of all tea changed. The tea included many loose-leaf styles, to preserve the delicate character favored by court society, and it is the origin of today’s loose teas and the practice of brewed tea. A powdered form of tea also emerged. Steaming tea leaves was the primary process used for centuries in the preparation of tea. After the transition from compressed tea to the powdered form, the production of tea for trade and distribution changed once again.

The Chinese learned to process tea in a different way in the mid-13th century. Tea leaves were roasted and then crumbled rather than steamed. By the Yuan and Ming dynasties, unfermented tea leaves were first pan-fried, then rolled and dried. This stops the oxidation process which turns the leaves dark and allows tea to remain green. In the 15th century, oolong tea, where the tea leaves were allowed to partially ferment before pan-frying, was developed.[31] Western taste, however, preferred the fully oxidized black tea, and the leaves were allowed to ferment further. Yellow tea was an accidental discovery in the production of green tea during the Ming dynasty, when apparently sloppy practices allowed the leaves to turn yellow, which yielded a different flavour as a result.[32] Tea production in China, historically, was a laborious process, conducted in distant and often poorly accessible regions. This led to the rise of many apocryphal stories and legends surrounding the harvesting process. For example, one story that has been told for many years is that of a village where monkeys pick tea. According to this legend, the villagers stand below the monkeys and taunt them. The monkeys, in turn, become angry, and grab handfuls of tea leaves and throw them at the villagers.[33] There are products sold today that claim to be harvested in this manner, but no reliable commentators have observed this firsthand, and most doubt that it happened at all.[34] For many hundreds of years the commercially used tea tree has been, in shape, more of a bush than a tree.[35] “Monkey picked tea” is more likely a name of certain varieties than a description of how it was obtained.[36]

In 1391, the Hongwu emperor issued a decree that only loose tea would be accepted as a “tribute”.[37] As a result, tea production shifted from cake tea to loose-leaf tea and processing techniques advanced, giving rise to the more energy efficient methods of pan-firing and sun-drying, which were popular in Jiangnan and Fujian respectively. The last group to adopt loose-leaf tea were the literati, who were reluctant to abandon their refined culture of whisking tea until the invention of oolong tea.[38] By the end of the 16th century, loose-leaf tea had entirely replaced the earlier tradition of cake and powdered tea.[39]

In Japan, During the Sui dynasty in China, tea was introduced to Japan by Buddhist monks. Tea use spread during the 6th century AD.[40] Tea became a drink of the religious classes in Japan when Japanese priests and envoys, sent to China to learn about its culture, brought tea to Japan. Ancient recordings indicate the first batch of tea seeds were brought by a priest named Saichō in 805 and then by another named Kūkai in 806. It became a drink of the royal classes when Emperor Saga encouraged the growth of tea plants. Seeds were imported from China, and cultivation in Japan began. In 1191, Zen priest Eisai introduced tea seeds to Kyoto. Some of the tea seeds were given to the priest Myoe Shonin, and became the basis for Uji tea. The oldest tea specialty book in Japan, Kissa Yōjōki, How to Stay Healthy by Drinking Tea, was written by Eisai. The two-volume book was written in 1211 after his second and last visit to China. The first sentence states, “Tea is the ultimate mental and medical remedy and has the ability to make one’s life more full and complete.” Eisai was also instrumental in introducing tea consumption to the warrior class, which rose to political prominence after the Heian period.

Green tea became a staple among cultured people in Japan, a brew for the gentry and the Buddhist priesthood alike. Production grew and tea became increasingly accessible, though still a privilege enjoyed mostly by the upper classes. The tea ceremony of Japan was introduced from China in the 15th century by Buddhists as a semi-religious social custom. The modern tea ceremony developed over several centuries by Zen Buddhist monks under the original guidance of the monk Sen no Rikyū . In fact, both the beverage and the ceremony surrounding it played a prominent role in feudal diplomacy.

In 1738, Soen Nagatani developed Japanese sencha, literally simmered tea, which is an unfermented form of green tea. It is the most popular form of tea in Japan today. The name can be confusing because sencha is no longer simmered. While sencha is currently prepared by steeping the leaves in hot water, this was not always the case. Sencha was originally prepared by casting the leaves into a cauldron and simmering briefly.[41] The liquid would then be ladled into bowls and served. In 1835, Kahei Yamamoto developed gyokuro, literally jewel dew, by shading tea trees during the weeks leading up to harvesting. By the 20th century, machine manufacturing of green tea was introduced and began replacing handmade tea.

A classical Japanese Tea Preparation Ceremony surrounded by Elements Conducive to Peace Generation. This Ceremony is an extended prelude to the Tea Drinking itself [42]

In Korea, the first historical record documenting the offering of tea to an ancestral god describes a rite in 661 AD in which a tea offering was made to the spirit of King Suro, the founder of the Geumgwan Gaya Kingdom. Records from the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) show that tea offerings were made in Buddhist temples to the spirits of revered monks. During the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), the royal Yi family and the aristocracy used tea for simple rites. The “Day Tea Rite” was a common daytime ceremony, whereas the “Special Tea Rite” was reserved for specific occasions. Toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, commoners joined the trend and used tea for ancestral rites, following the Chinese example based on Zhu Xi’s text formalities of family. Stoneware was common, ceramic more frequent, mostly made in provincial kilns, with porcelain rare, imperial porcelain with dragons the rarest. The earliest kinds of tea used in tea ceremonies were heavily pressed cakes of black tea, the equivalent of aged pu-erh tea in China. However, importation of tea plants by Buddhist monks brought a more delicate series of teas into Korea, and the tea ceremony. Green tea, “Jakseol” or “Jungno”, is most often served. However, other teas such as “Byeoksoryeong” Cheonhachun, Ujeon, Okcheon, as well as native chrysanthemum tea, persimmon leaf tea, or mugwort tea may be served at different times of the year.

The Bottom Line, is “Tea is the elixir of life”.[43] It is also recorded in the annals of history that, “Tea is the ultimate mental and medical remedy and has the ability to make one’s life more full and complete.” These are the famous words of Eisai, the influential Japanese monk known for introducing green tea from China to Japan in the early 12th century.[44] The origins and history of tea date back almost 7,000 years and tea itself is now commercially available in more than 3,000 different variations. The most widely consumed beverage in the world has both a historical and cultural importance that cannot be rivalled. Tea, in its present format, irrespective of the ritual, traditional and ceremonial aspects, is an aromatic beverage prepared by pouring hot or boiling water over cured or fresh leaves of Camellia sinensis[45], an evergreen shrub native to East Asia which probably originated in the borderlands.

For millennia, tea was a medicinal beverage obtained by boiling fresh leaves in water, but around the 3rd century CE, it became a daily drink, and tea cultivation and processing began. Over the centuries, tea has undoubtedly resulted in an impact on humanity, in general. In several instances, tea has acted as a catalyst for historical change. This is detailed in the book, “A History of the World in 6 Glasses[46]”, the author outlines the many reasons why this is true. The most obvious historical change that tea caused was of course the Boston Tea Party, but there is also another story, which is less well-known. When tea was introduced to Great Britain in 1662, it was only readily available to the wealthier class.

The cost for the lower class was too high and so they turned to alternative methods for acquiring tea at a cheaper price. Tea smuggling was a popular trade at the time. It was a popular commodity, easy to store and very light. The majority of tea smugglers came from China, and this meant that legitimate tea sellers in Britain were losing money to the black-market tea trade. They were also losing money due to China’s restrictions on the trade of opium. This became an enormous problem for the British government to handle so the British East India Company decided to learn how to make tea on their own. They sent spies into the ports of China to learn the mysterious methods of how to grow and harvest tea leaves. The spies had to dress in traditional Chinese attire and bring translators, as the Chinese were not welcoming to foreigners. Many of the spies were successful in acquiring tea, but the long trek back to England was often too much for the delicate leaves.

As the spies snooped around China, the Chinese government was struggling to deal with their population, which was highly addicted to opium. The country was losing finance rapidly. In the interim, Britain was grappling with the problem as to how to legally sell opium in China and as they entered into a war with China, the sale of tea is what kept them from bankruptcy and essentially funded their military ventures. Their newfound tea sales as well as some of the tea spies turning to military spies aided Britain in sustaining the Opium Wars[47], long enough to win.[48] Using this strategy, the humble tea played a significant role in determining the outcome of the Opium Wars, much to the relief of Great Britain. However, Great Britain probably not thankful when tea made its next appearance in Boston.[49]

Although health benefits have been assumed throughout the history of using Camellia sinensis as a common beverage, there is no high-quality evidence that consuming tea confers significant benefits other than possibly increasing alertness, an effect caused by caffeine in the tea leaves.[50] In clinical research conducted over the early 21st century, tea has been studied extensively for its potential to lower the risk of human diseases, but there is no good scientific evidence to indicate that consuming tea affects any disease or improves health.[51]

However, the South African indigenous Rooibos tea[52], which is not from traditional tea leaves, hence not an “authentic tea”, made from the shrub, Aspalathus linearis, is ideal, since it is calorie-free and its naturally sweet taste, means no sweeteners are necessary. In addition, Rooibos contains active compounds that can help control blood glucose, while lowering inflammation.[53] Research has demonstrated the antioxidant activity and protective effect on DNA strand scission of Rooibos tea and appears promising in the management of Alzheimer’s Disease and control of blood sugar in Diabetes Mellitus.[54]

While tea may be a simple beverage, it had an enormous impact on the world, ranging from improving global trade, to possibly reducing the risks of non-communicable diseases,[55] to becoming an important part of our individual, daily lives, globally.[56]

References:[1] https://i.pinimg.com/originals/e9/e4/95/e9e4956e926b68de6d70e7c3c3e6327d.jpg

[2] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346303227_Exploitation_of_Tea-Plantation_Workers_in_Colonial_Bengal_and_Assam

[3] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=7f5274a4e8c186c3JmltdHM9MTY2NTEwMDgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE3OA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Hoshikawa+Tea+origin+1978&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cudGVhc2Vuei5jb20vY2hpbmVzZS10ZWEvdGVhLWhpc3RvcnkuaHRtbA&ntb=1

[4] https://thecirclecomposition.org/content/images/size/w1140/2021/12/pexels-pixabay-39347.jpg

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFYamamotoKimJuneja1997

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFHeissHeiss2007

[7] https://books.google.com/books?id=gxCBfNmnvFEC&pg=PT31

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#Martin

[9] https://books.google.com/books?id=YdpL2YCGLVYC&pg=PA63

[10] https://books.google.com/books?id=YIyV_5wrplMC&pg=PA26

[11] https://books.google.com/books?id=mZ0TUWvE9qQC

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Chow%20pp.19%2D20%20(Czech%20edition)%3B%20also%20Arcimovicova%20p.9%2C%20Evans%20p.2%20and%20others

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Lu%20Ju%20pp.29%2D30%20(Czech%20edition)

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=%5E-,Chow%20pp.20%2D21,-%5E%20Evans%20p

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=%5E-,Evans%20p.%203,-%5E

[16] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4704058

[17]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4704058

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_Encyclopedia

[19] https://web.archive.org/web/20080308234307/http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761563182/Tea.html

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFMairHoh2009

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFMairHoh2009

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFMairHoh2009

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFMairHoh2009

[24] https://books.google.com/books?id=AGaTAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA28

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#Martin

[26] https://books.google.com/books?id=XF17CAAAQBAJ&pg=PA42

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Pettigrew%2C%20Jane%20(2009).%20%22The%20discovery%20of%20Tea%22.%20afternoon%20tea.%20PITKIN.%20p.%C2%A010.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D84165%2D143%2D9.%20Known%20as%20the%20%27Elixir%20of%20Life%27

[28] Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World’s Most Popular Drug. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-0415927222.

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#CITEREFMairHoh2009

[30] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=bf19e0dbbb39658dJmltdHM9MTY2NTEwMDgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTc2OA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=The+history+of+tea+spreads+across+multiple+cultures+over+the+span+of+thousands+of+years.+With+the+tea+plant+Camellia+sinensis+native+to+East+Asia+and+probably+originating+in+the+borderlands+of+southwestern+China+and+northern+Burma&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvSGlzdG9yeV9vZl90ZWEjR2VvZ3JhcGhpY19vcmlnaW5z&ntb=1

[31] James A. Benn (2015-04-23). Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History. Hong Kong University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9789888208739.

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Mair%20%26%20Hoh%202009%2C%20pp.%C2%A0118.

[33] https://archive.org/details/anhistoricalacc00staugoog

[34] https://archive.org/details/ajourneytoteaco00fortgoog

[35] https://archive.org/details/wanderingsinchi02cummgoog

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-0-8048-3724-8

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=James%20A.%20Benn%20(2015%2D04%2D23).%20Tea%20in%20China%3A%20A%20Religious%20and%20Cultural%20History.%20Hong%20Kong%20University%20Press.%20p.%C2%A0173.%20ISBN%C2%A09789888208739.

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Tu%2C%20Long%20(1887).%20Kaopan%20yushi.%20China%3A%20Shanyin%20songshi.%20p.%C2%A0212.

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Nguy%2C%20Andrew%20(2019).%20A%20Tale%20of%20Two%20Teas%3A%20The%20Rise%20of%20Loose%2DLeaf%20Tea%20in%20China%20and%20Japan.%20Claremont%2C%20California%3A%20Pomona%20College.%20p.%C2%A042.

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Kiple%2C%20Kenneth%20F.%3B%20Ornelas%2C%20Kriemhild%20(2000).%20The%20Cambridge%20World%20History%20of%20Food.%20Vol.%C2%A02.%20Cambridge%2C%20UK%3A%20Cambridge%20University%20Press.%20p.%C2%A04.%20ISBN%C2%A00%2D521%2D40216%2D6.

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Kumakura%2C%20Isao%20(1976).%20%22Senchashi%20joko%3A%20Nihon%20to%20Chosen%22.%20Fuzoku%3A%20Nihon%20Fuzokushi%20Gakkai%20Kaishi.%2014%3A%209.

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tea_ceremony_performing_2.jpg

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea#:~:text=Pettigrew%2C%20Jane%20(2009).%20%22The%20discovery%20of%20Tea%22.%20afternoon%20tea.%20PITKIN.%20p.%C2%A010.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D84165%2D143%2D9.%20Known%20as%20the%20%27Elixir%20of%20Life%27

[44] https://www.bing.com/search?q=Tea+is+the+ultimate+mental+and+medical+remedy+and+has+the+ability+to+make+one%27s+life+more+full+and+complete&form=ANNTH1&refig=f0702517c5c04ee8afa50034cc9f352b#:~:text=Date-,Eisai,-%E2%80%9CTea%20is%20the

[45] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=5232edd8b91e26e7JmltdHM9MTY2NTEwMDgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTIwMA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Camellia+sinensis&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQ2FtZWxsaWFfc2luZW5zaXM&ntb=1

[46] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=859410012532976eJmltdHM9MTY2NTEwMDgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE5NQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=A+History+of+the+World+in+6+Glasses&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZHJlYWRzLmNvbS9ib29rL3Nob3cvMzg3Mi5BX0hpc3Rvcnlfb2ZfdGhlX1dvcmxkX2luXzZfR2xhc3Nlcw&ntb=1

[47] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=a592917eb16ca2dfJmltdHM9MTY2NTEwMDgwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTIyMA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Opium+Wars&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvT3BpdW1fV2Fycw&ntb=1

[48] https://sites.psu.edu/lexiemarottapassion/2015/10/23/how-tea-changed-the-world-a-brief-history-lesson/

[49] https://www.bing.com/search?q=boston+tea+party+definition&form=ANNTH1&refig=446b773c76694061abb2d0657a098bf7&sp=5&qs=MT&pq=boston+tea+party&sk=AS1MT3&sc=10-16&cvid=446b773c76694061abb2d0657a098bf7#:~:text=Look%20it%20up-,Bos%C2%B7ton%20Tea%20Party,-%5BBoston%20Tea%20Party

[50] https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/natural/997.html

[51] https://nccih.nih.gov/health/greentea

[52] https://www.bing.com/search?q=what+is+rooibos+tea+made+of&form=ANNTH1&refig=1953c94fde544f8ab3311cf9d21af06c&sp=4&qs=UT&pq=what+is+rooibos+tea&sk=MT3&sc=10-19&cvid=1953c94fde544f8ab3311cf9d21af06c

[53] https://www.joekels.co.za/blogs/rooibos-health/how-diabetics-can-benefit-from-drinking-rooibos

[54] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8101211_Antioxidant_activity_and_protective_effect_on_DNA_strand_scission_of_Rooibos_tea_Aspalathus_linearis

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_effects_of_tea

[56] https://thecirclecomposition.org/how-tea-affected-humanity/

[57] https://i.pinimg.com/originals/77/41/f0/7741f01ed8d61e6f39f58a744232032c.jpg

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: British Colonialism, British empire, Colonization, English Colonialism, Exploitation, India, Racism, Slave labor

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 10 Oct 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: “Peace in a Cup of Tea” (Part 1): The Beginning, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.